August 19, 1691

The battles with the Turk were not just a success for the Habsburgs but for much of Christian Europe, aside from France. 7 On 5 March 1684, Pope Innocent XI had sponsored a new and highly effective Holy League for a war that was to last until final victory, and no party was to make a separate peace with the Ottomans. Even the Czar of Muscovy was invited to join. This alliance was to produce immediate, concerted action – the Habsburgs in Hungary, the Poles in lands north of the Dniester and the Venetians in the Adriatic, the Mediterranean, and in Greece. 8 The strategic concept – squeezing the Ottomans on every side – put decisive pressure on the Turks. The decade of active campaigning seasons after the occupation of Buda was marked by a series of extraordinary victories in the field. The common name now given to this period of war in Austrian history is the `Age of Heroes’ (Heldenzeitalter): the heroes included Charles of Lorraine, `Türkenlouis’ – Ludwig Wilhelm of Baden, Guido von Starhemberg (cousin of Rüdiger), Florimond de Mercy, and many others who had made their names in the east, but later also fought with equal success against the armies of France in Western Europe during the War of the Spanish Succession. Thereafter, with the exception of the spare figure of Prince Eugene of Savoy, the greatest hero of all, they grew old and fat, died or retired, and Austria stultified. There had been a string of six miraculous victories, which people could recite like a litany. The first, of course, was the salvation of Vienna by King John Sobieski of Poland. The second was Charles of Lorraine storming Buda in 1686 with the old pasha lying dead by the gate. The third was the Battle of Nagyharsany in 1687, often called `the second Mohacs’, the capstone to Charles of Lorraine’s triumphs; the memory of Suleiman I destroying the old Kingdom of Hungary at Mohacs in 1526 had finally been redeemed. The fourth victory was the Elector Max Emmanuel of Bavaria’s who captured Belgrade, the city of battles, in 1688; the Turks recaptured it the following year. `Türkenlouis’ destroyed the Turkish army at the Battle of Slankamen in 1691. In the sixth battle at Zenta in 1697 Prince Eugene of Savoy humiliated the Sultan Mustafa, who fled from the battlefield in panic, leaving the River Tisza filled with the Ottoman dead. Fourteen campaigning seasons finally brought a settlement, and in a little pavilion by the town of Karlowitz near Belgrade peace was signed in 1699.

These victories were the more remarkable because they were gained with limited resources. The renewal of war in the west against France meant that the Habsburgs, like the Ottomans, were now fighting two enemies at once. So at Slankamen, forty miles north of Belgrade, on 19 August 1691 Ludwig Wilhelm of Baden had only twenty thousand men against a much larger Ottoman army, led by another vigorous Köprülü, Fazil Mustafa Pasha. `Türkenlouis’ won, in part because the Ottomans lacked the vital Tartar component of their army, which was still travelling south, and partly because his small but battle-hardened regiments could respond precisely and effectively to his command. But perhaps most important of all was a lucky chance of war. A stray bullet killed the Ottoman commander and his army immediately disintegrated, abandoned all its artillery and even the army war chest, and fled back towards the safety of Belgrade. Had the reverse happened, and `Türkenlouis’ ended his days on the battlefield, his small force would not have fallen apart. Another senior officer would have assumed command and carried on the battle, while planning the withdrawal. This fragility was inherent in the Ottoman system: an Ottoman army without its head was no more than a rabble. But as the Habsburg army dwindled in numbers (mostly through sickness) and lacked men, food and money, it was soon just as demoralised. One Englishman said that the army protecting the bridge at Osijek `look generally like dead men’

The Campaign

At the outbreak of the Nine Years War, caused partly by Louis XIV’s mounting anxiety at Habsburg gains in the Balkans. The withdrawal of the Kreistruppen and most of the other Germans reduced the imperialist to barely 24,000 effectives and undoubtedly robbed Leopold of the best chance to extend his conquests. It was only thanks to the continuing chaos in the Ottoman empire that any further advance was possible. The margrave of Baden-Baden, the new field commander, pushed south seizing Nis (Nish) in Serbia in September 1689. Marshal Piccolomini was then detached southwards into Bosnia and Albania, while Baden captured Vidin in northwestern Bulgaria. Piccolomini was welcomed by the Serbian and Albanian Christians but had to abandon Skopje because of the plague. He succumbed on 9 November, robbing the imperialists of an able negotiator, skilled at striking deals with local leaders. By January 1690 the imperialist position was beginning to crumble when 2,200 men were lost at Kacanik, representing nearly a third of the force in Bosnia and a sizeable proportion of the now much-reduced army. To sustain the momentum, Leopold issued his famous declaration to the Balkan Christians guaranteeing them religious freedom and preservation of their privileges if they accepted him as hereditary ruler. The response was disappointing. The Bulgarian Catholics had been massacred after the failure of the Ciporvci rising and the Macedonians who rebelled in 1689 met a similar fate. The faltering Habsburg advance discouraged others from attempting the same. Meanwhile, the sultan had recovered control of his army and proclaiming Thököly prince of Transylvania, he sent 16,000 troops to overrun that country in August 1690. To counterattack Baden turned north with 18,000, defeating Thököly by September. It proved a pyrrhic victory. In his absence the Ottomans invaded Serbia with 80,000 men, recapturing all the towns along the lower Danube, including Belgrade guarding the entrance to the Hungarian Plain. The rapid loss of this great city was a major strategic and psychological blow, triggering a wave of refugees from the areas south of the Danube.

By now, Leopold’s western allies had become concerned that Austria had become too deeply embroiled in the Balkans to prosecute the war on the Rhine with the necessary vigour. However, the Anglo-Dutch-sponsored peace talks broke down in 1691 because both sides still believed they could win an outright victory. Determined to succeed, Leopold did just what William III feared and recalled all but five and a half regiments from his force on the Rhine. New treaties were concluded with Brandenburg and Bavaria to obtain additional assistance, and Baden advanced to defeat the 120,000-strong Ottoman army at Slankamen on 19 August 1691. Fought in almost unbearable heat, the action proved costly to both sides, Baden losing 7,000 to the 20,000 of his opponents. By the end of the year Baden’s army had fallen to only 14,000 effectives, but the victory stabilized the Hungarian front and secured the imperial recovery in Transylvania.

Battle

The clash between the two forces took place on the west side of the Danube, opposite the outlet of the Tisa. Both armies deployed near Zemun, but the superior Ottoman army at first didn’t attack for two days. Then Baden-Baden tried to provoke the attack, by withdrawing slowly to a fortified position near Slankamen. The Ottomans followed and surrounded the Imperial Army. By August 19, the heat, disease and desertion had reduced both armies to 33,000 and 50,000 able men. On that day the Ottoman cavalry finally attacked.

These were unorganized charges, however; although huge, the Ottoman forces were poorly armed and no match for the firepower of Louis of Baden’s German-Austrian infantry and field guns. Additionally, the Ottomans’ supply system was incapable of waging a long war on the empty expanses of the Pannonian plain. Initially the Ottomans were at an advantage, as they advanced and burned 800 supply wagons of the Imperial Army. Louis of Baden, in a desperate situation, broke out of his position, besieged by the Ottomans, and turned their flanks with his cavalry, inflicting fearful carnage. After a hard battle, the 20,000-man Imperial Army with 10,000 Serbian militia led by Jovan Monasterlija was victorious over the larger Ottoman force. The death of Grand Vizier Köprülü Fazıl Mustafa Pasha during mid-battle caused the Ottoman morale to drop and the army to disperse and retreat.

Without adequate forces, Baden could do little more than hold the line and he was soon transferred to the Rhine for a similar holding operation against the French. The stalemate was sustained in the Balkans by the arrival of more German auxiliaries in 1692-6. Attempts to take Belgrade (1693), Peterwardein (1694) and Timisoara (1696) ended in failure, while the Turks continued to inflict minor defeats on isolated imperial detachments. Though the commanders were repeatedly blamed for the setbacks, the real problem was insufficient manpower.

A very rare broadside with Ottoman script showing the Battle of Slankamen was made in the series of large separately published maps by the Turkish War Office the late Hamidian period as a part of intellectual propaganda to revive patriotic sentiment.

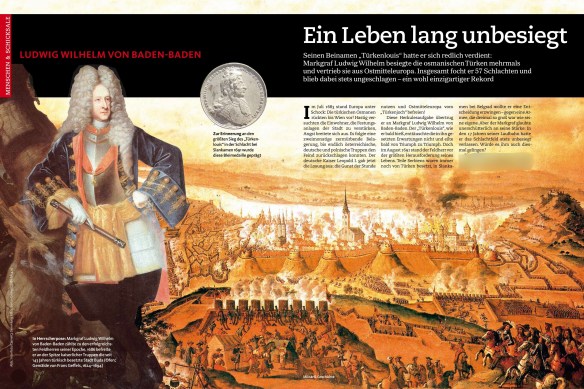

Louis-Guillaume (Ludwig-Wilhelm), Margrave of Baden (1655-1707), born in Paris, was an Imperial field commander with a long military career and well-established reputation in fighting the Ottomans in southeastern Europe. He earned the nickname `Turkenlouis’ and won a significant victory at Slankamen in 1691. Baden captured the fortress of Landau in Alsace from the French in 1702, but was subsequently defeated at Friedlingen by Villars, a victory which earned the French commander his marshal’s baton. Although overly proud and sensitive, and difficult to deal with, Baden was brave enough, and his assistance was crucial to the success of Marlborough’s attack on the Schellenberg, where the Margrave was shot in the foot, a wound that refused to heal properly.

His assignment in August 1704 to lay siege to Ingolstadt on the Danube excluded him from the victory at Blenheim, and it is often said that this was deliberate policy on the part of Marlborough and Eugene to keep Baden out of the way. This seems improbable as the fortress was an important place, the possession of which would have been crucial if Marlborough had not been able to bring the French and Bavarians to battle and win so decisively. Accordingly, the margrave’s task was not a trivial one, and it is unlikely that Marlborough and Eugene foresaw the chance of decisive action on the plain of Höchstädt quite that clearly and so far in advance, or that they would lightly give up a numerical advantage of almost 15,000 troops in order to sideline their colleague. Baden’s failure to rendezvous with Marlborough in 1705 led to the abandonment of the Moselle campaign (which was languishing anyway), but the margrave was undoubtedly a sick man, with a festering wound. His lameness, however, did not prevent his showing Marlborough around the ornate gardens of his home on one occasion. Baden died three years later, a disappointed man, snubbed and ignored by the emperor in Vienna to whose family he had rendered long and loyal service.

During the second half of the seventeenth century, the highest level of command came to be that of Generalleutnant who was the acting commander-in-chief. After the Thirty Years War this position was held successively by Ottavio Piccolomini (1648–56), Raimondo Montecuccoli (1664–80), Charles V Duke of Lorraine (1680–90), Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden-Baden (1691–1707) and Eugene of Savoy (from 1708 until his death in 1736).

The most important battles of the “Türkenlouis” – LUDWIG WILHELM VON BADEN-BADEN

In the French-Dutch War (1672-1678)

1676: Siege of Philippsburg

In the Great Turkish War (1683-1699)

1683: Battle of Kahlenberg near Vienna

1683: Battle of Pressburg (Slovakia)

1684: siege of Gran (Hungary)

1684: 1st Siege of Buda (Hungary)

1686: 2nd Siege of Buda

1687: Battle of Mohács (Hungary)

1688: Battle of Derventa (Bosnia)

1688: 1st Siege of Belgrade (Serbia)

1689: Battle of Nissa (Serbia)

1690: 2nd Siege of Belgrade

1691: Battle of Slankamen (Serbia)

In the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714)

1702: Battle of Friedlingen (Baden-Württemberg)

1704: Battle of Schellenberg (Bavaria)

1705: Battle of Pfaffenhofen (Bavaria)