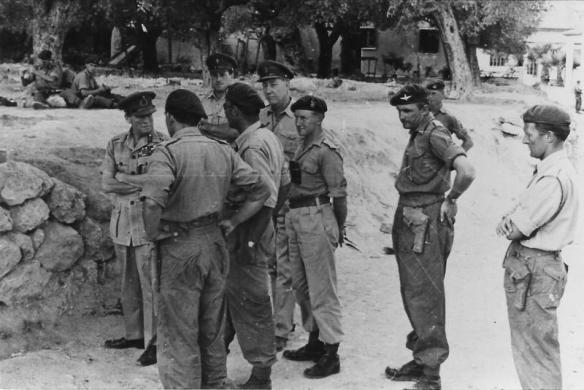

Senior officers discuss plans for Op Sparrowhawk against EOKA terrorists, Cyprus, October 1956.

(September to December 1956)

The international crisis in the Near East had sharpened after Colonel Nasser officially assumed power as President of Egypt on 23 June 1956. He had then blockaded the Suez Canal with sunken ships and crippled the vital arterial trade route between Europe and the Middle East and Far East. Hostilities apparently imminent with Egypt, Lieutenant General Keightley was warned to prepare Cyprus and Malta as invasion assembly points for 80,000 troops. Since the RASC remained vital in ferrying men, equipment and supplies to and from the embarkation ports, 1 Transport Column was reformed into RASC Cyprus East and Cyprus West.

Determined to ensure that Cyprus remained in the international limelight, Grivas kept up the pressure on internal security with hit-andrun attacks and ambushes. Between 7 August and 15 September, which was the scheduled D-Day to land in Egypt, EOKA carried out fifty-six bombings of military targets including eighteen directed at Dhekelia, Akrotiri, Episkopi and the 625 Ordnance Depot in Larnaca and fourteen against camps in the Nicosia area. There were twenty attacks on military logistic facilities at Famagusta, Limassol and Paphos. An Army Field Security launch was also sunk. Most of the devices were delivered by employees. At least twenty were defused. There were twenty ambushes of military vehicles. In August, twelve loyalist Greek-Cypriots were murdered. As part of the plan to seize hostages in retaliation for the imminent execution, on 4 August, of the three EOKA who had killed Lance Corporal Morun, on the 3rd, Mr John Cremer, an elderly retired civil servant thought by EOKA to be an intelligence agent, was kidnapped as he walked to teach English in the Turkish hamlet of Temblos, west of Kyrenia. The authorities responded that the ‘course of justice would not be affected’ by the kidnapping, and Grivas’s strategy backfired when Andreas Zakos appealed from his death cell that Cremer should be released, which he was three days later. When the three were hanged on the 9th, the expected retaliation did not materialize; instead, a week later, Grivas suspended operations to allow Archbishop Makarios to negotiate ‘a free Cyprus’. The reality was that some communities fed up with the collective fines, roadblocks, cordon-andsearches, curfews and EOKA executions and punishment squads in the mid-summer heat, quite apart from the withdrawal of business investment, were challenging his orders for diversionary operations to deflect the pressure from the mountain Guerrilla Groups. The flow of informant information also increased.

On the 22 August Field Marshal Harding surprised diplomats by offering EOKA the option of either renouncing their British citizenship and being deported to Greece until the Emergency was resolved or taking their chances in court. To prevent the British claiming victory if EOKA accepted, the Greek Government offered safe passage to Grivas and his men. But Grivas, feeling that the struggle was by no means lost and judging the offer to his men to keep their British citizenship to be a touch arrogant, stuck to his principle of diplomacy through force by announcing next day, ‘My reply to the Government is No! Come and take it’ and that operations would resume on 27 August. Harding then revealed on 26 August that a week earlier a patrol had found diaries belonging to Grivas in jars near Lysi. For a few weeks after 1 April 1955, Grivas had stayed with a cousin of Afxentiou, who had become a bodyguard to Grivas. The bodyguard and his brother had undertaken to take the diaries to Lysi where they buried them in a field. In the same period, Grivas had also stayed with a man who knew where they were buried and had sold them to the British. They proved to be an intelligence coup of some significance because they described the organization, methods and personalities of EOKA during the run-up to the outbreak of the violence in April 1955. The extracts again undermined Makarios by proving that he was deeply involved in the insurrection and that it was he who had invited Grivas to form a clandestine army to liberate Cyprus. For the third time Grivas had compromised EOKA in ignoring his own principles by failing to destroy correspendence and documents. His claims that the diaries were forgeries were largely ignored.

The day of 27 August was tense, particularly in Ledra Street where businesses had enjoyed a week of welcome trading during the ceasefire, including from Service families, even though the street now had achieved international fame as Murder Mile. The street ran through Old Nicosia. At 57 Alexander Road, a few steps from Ledra Street, lived Dr Michael Grivas, elder brother to Colonel Grivas. The narrowness and hustle and bustle of the street in Old Nicosia allowed gunmen to identify their target, usually approach from behind, shoot at point blank range and then disappear, guns sometimes being handed to EOKA women who concealed them in shopping bags. Patrols were also easy targets. RASC Private Douglas Laventure was the first off-duty soldier to be murdered on Murder Mile, while he was purchasing a present eleven days before Christmas 1955. Private Raymond Banks, of 1 South Staffords was killed on 21 May 1956 when a grenade was dropped into his vehicle from an upper storey of a house. In mid-June 1956 a Warwicks patrol was ambushed, and although the radio operator, Private Ray Watkins, was badly wounded in both arms and legs, he maintained contact with Battalion HQ. It was not uncommon for Greek-Cypriot residents and shoppers to walk past victims lying in the road and pretend to know nothing about it. Patrols and families soon learnt that if shops were closed and there were few shoppers at times when it should be busy, then something was amiss.

Within hours of the ceasefire being lifted, a bomb exploded at an officer’s house, a tank landing ship was damaged by a limpet mine, a fire destroyed the new Officers’ and Sergeants’ Messes at Episkopi and power lines near Paphos were sabotaged. A new dimension to Service life in Cyprus emerged when Greek-Cypriot NAAFI employees deposited bombs in Army married quarters. In another engagement in central Nicosia, two Service wives were caught in crossfire during a thirty-minute gun battle in which a patrol was ambushed.

When Polycarpos Georghadjis, the young hard-core guerrilla who had developed an intelligence network among the Cyprus Police, was detained in Nicosia Prison, Grivas considered him to be of such importance that he instructed the Nicosia EOKA murder group led by Nicos Sampson to rescue him. Born Nicos Georghiades in Famagusta, Sampson changed his name when he began working as a photojournalist for the Times of Cyprus in order to distinguish himself from others with the same surname. The Times of Cyprus, was edited by Charles Foley and since it was pro-enosis was known by British soldiers as the EOKA Times. Also locked up in Nicosia Prison after her failed kidnap plan was Nitsa Hadjigeorghiou. She managed to contact Georghadjis and when she learnt on 30 August that he had convinced the prison authorities that he was unwell and was going for an X-Ray at Nicosia General Hospital on the next day, she persuaded a Greek-Cypriot warder to let Sampson know of Georghadjis’ appointment. Next day, Georghadjis and two other detainees arrived at the hospital escorted by Sergeants Tony Eden and Leonard Demmon (both Metropolitan Police). One of the detainees was Argyrious Karadymas, the Greek owner of the caique Ayios Georghias boarded by the Royal Navy in January 1955, and he had been sentenced to six years as an agitator. As the prisoners and escorts came down the stairs from X-Ray, four gunmen who had been waiting in the main entrance hall opened up with revolvers that had been smuggled into the hospital by EOKA women. Demmon returned fire with his Sterling but he had been badly wounded and accidently shot two hospital orderlies as well as one of the terrorists. Eden shot a second terrorist and killed a third by clubbing him with his revolver when his ammunition ran out, but he was unable to prevent Georghadjis and Karadymas from escaping through the back entrance. Eden was awarded the George Medal and, although a marked man, he refused to return to the UK. In December he was killed when his cocked revolver fell from his shoulder holster while he was playing with his puppy. Demmon was later posthumously awarded the Queen’s Police Medal for Gallantry. A week later, Pavlos Pavlakis and Antonios Papadopoulos of the Famagusta Group escaped from Pyla Detention Camp by crawling underneath the perimeter fence. Pavlakis assumed command of the Famagusta Town Group while his colleague joined Afxentiou.

As the Franco-British forces completed their final preparations for the landings in Egypt, Cyprus had become an enlarged aircraft carrier for the British and French army and air force units assembling in existing and hastily constructed camps. Among the French force was the 10th Airborne Division, which had three parachute regiments, one being Foreign Legion. It had recently been on operations in Algeria, where the French response to terrorism was considerably more robust than that of the British in Cyprus. Defending the anchorages and airfields was the 1st Artillery Group, Royal Artillery (1 AGRA) with 21 and 50 Medium Regiments RA replacing 40 Commando in Paphos and 2 Para in Limni Camp respectively, and the 16 and 43 Light and 57 Heavy Anti Aircraft Regiments RA. The naval elements were gathered in Malta where there were concerns that 3 Commando Brigade had been in Cyprus for nearly a year and had not exercised the complexities of an amphibious landing.

Much to his consternation, the influx of British and French troops forced Brigadier Baker to divert troops from some internal security operations to guard the camps springing up across the island, not only against EOKA but also the threat of Arab commando attacks. The inevitability of de-escalating internal security operations was also worrying, more so when industrial disputes and strikes led to troops being diverted to load ships at the embarkation ports. Privately, Field Marshal Harding was critical of the impact that the operation was having on his drive against EOKA, particularly as Operation Fox Hunter had dealt the Troodos Guerrilla Groups several severe blows. But EOKA would be given some respite when 16 Parachute Brigade was withdrawn from operations near Kambos and 1 and 3 Paras returned to Aldershot in several types of aircraft where, in rotation over ten days each, the soldiers carried out three training jumps and a battalion drop and had a couple of days leave before returning to Cyprus.

When in September the Limassol suburb in which he was hidden was subjected to an increasing numbers of searches, Grivas moved his hideout from the home owned by Dafnis Panayides to the house occupied by Marios Christodoules, his wife Elli and their baby daughter aged nine months, on the northern outskirts of Limassol. Ironically, Christodoules was a clerk at the Akrotiri branch of the Ottoman Bank. The hideout had been built by two members of Limassol Town Group, Andreas Papadopoulous and Manolis Savvides. Both were part of the syndicate successfully smuggling weapons with the connivance of Customs, indeed it was Savvides who had persuaded Christodoules to shelter Grivas. The hideout was accessed through a trapdoor under the kitchen sink and, dug under the garden, was topped by a concrete roof on which sat a poultry run. Behind the house was an escape route across fields. Inside there was sufficient room for two camp beds, a desk and a chair and an electric fan for ventilation. Grivas usually spent the day in the house; he rarely went out. As with other dynamic guerrilla leaders, Che Guevera being a classic example, some young women focused on Grivas, now aged fifty-eight years, among them Louella Kokkinou, whom he trusted highly as a courier. She claimed that her front teeth had been knocked out during an interrogation in May 1956 – until dental records proved they had been extracted in June. To help protect the bunker, Christodoules purchased a small black mongrel whose irritable, high-pitched barking warned of strangers approaching the property. Grivas’ presence in the bunker was known only to Dafnis and Maroulla Panayides, who had sheltered him previously and brought his correspondence, Demos Hjimiltis, the Limassol Town commander and his fiancée, Nina Droushiotou, who became the principal courier for Grivas, and the two builders. Elli Christodoules also seems to have hosted Grivas.

Grivas stepped up the campaign of terror, with Greek-Cypriots again taking the brunt of civilian deaths. During the afternoon of 8 September, eight EOKA from the Tassos Sofocleus Group breaking into Kyrenia Police Station were interrupted when Captain de Klee, Scots Guards attached to the Guards Independent Parachute Company, and Cornet Gage of the Royal Horse Guards, walked into the police station and startled the terrorists. Thinking that the two men were part of an Army patrol, the raiders scuttled past the two officers, dropping weapons and ammunition in their wake. Ten soldiers were killed in the second half of September, including during the morning of the 28th, Surgeon Captain Gordon Wilson, the Royal Horse Guards Medical Officer, shot by Nicos Sampson in his car at the junction of St Andrew and Queen Frederica Street in Nicosia soon after he had treated a seriously-ill Greek-Cypriot woman. Two shops suspected to have been involved in the murder were searched and closed. Next day, Sampson was one of three EOKA who shot Sergeant Cyril Thorogood (Leicester and Rutland Constabulary) and Sergeant Hugh Carter (Herefordshire County Constabulary) at point blank range and badly wounded Sergeant William Webb (Worcestershire County Constabulary) at the junction of Alexander the Great Street with Ledra Street while they were getting into a car after a shopping trip. Several British wives gave first aid to Thorogood and Carter while Webb, shot several times, attempted to engage the gunmen. Sampson found sanctuary in St Andrew’s Monastery. On the same day, a 14/20th Hussars sergeant was shot dead and his wife wounded in front of their young daughter as they were returning from church in Larnaca. Two Greek-Cypriots were arrested, and another suspected to have been involved was Petrakis Kyprianou, the well-educated if rebellious son of a prosperous grocer. He had volunteered to attack a Royal Navy party ashore, but when this failed he had then led grenade attacks on Army vehicles and had been involved in the execution of Greek-Cypriots. He vowed never to be taken alive and was granted his wish in an engagement with troops in March 1957.

Losing patience with Greek-Cypriots’ persistent reluctance to identify the killers and their unwillingness to help casualties, the authorities imposed a 7 am to 7 pm curfew on several Greek-Cypriot suburbs in the walled city, with a one-hour suspension at midday. Several thousand people evacuated their homes, leaving about 12,000 under curfew. Greek-Cypriot hotel bars, cabarets, cinemas and theatres and coffee shops were ordered to close, although hotels could cater for residents. On 1 October, when several hundred women intent on restocking empty larders attempted to access a Turkish vegetable market but found their way blocked by soldiers from 1 KOYLI, the District Commissioner agreed to a two-hour suspension either side of midday so that they could buy provisions from Greek-Cypriot markets. He also organized food centres along Ledra Street to ensure equitable distribution. After the Mayor of Paphos had complained that the curfew was causing excessive hardship because wage earners were unable to go to work, Harding raised the restrictions on 6 October.

Among the military casualties in late September were Corporal Paul Farley and Staff Sergeant Joe Culkin, both of 1 Ammunition Disposal Unit (Internal Security), killed within ten days of each other while dealing with devices in EOKA hideouts. From the earliest stages of its campaign, EOKA lacked explosives. After the seizures and non-arrival of explosive during the preparatory stages, EOKA divers had recovered landmines from captured Italian stocks dumped in the shallow waters off Famagusta, and although they were usually corroded, the TNT was sufficiently stable to be extracted and hammered into small lumps of explosive or crystals. Fishermen knew where the mines could be found because they sometimes dragged them in their nets and then used the explosive to stun fish. Local information enabled EOKA to map the locations of minefields used to defend Cyprus during the war and after lifting mines they then used the serviceable ones to ambush military vehicles. Detonators and dynamite were stolen or bought cheaply from the copper mines, quarries and road works. Potassium chlorate was widely used for agricultural purposes and mixed with sugar could be converted into improvised if unstable explosive. In spite of Army objections, it was not until late in the Emergency that the supply to farmers was strictly rationed.

Hand grenades smuggled to Cyprus included the British Mills 36, one of the three types of red-painted Italian Anti Personnel bombs known as ‘Red Devils’ and post-war US grenades supplied to the Greek Army. Improvised alternatives were nails, bits of metal and iron and stones packed into a covered tin can or perhaps a parcel surrounding a tube of improvised explosive into which was inserted a fuse detonated with a match or lighter. The ‘pipe bomb’ was popular. Manufactured from standard plumbing pipe filled with TNT and fitted at both ends with screw caps, grooves weakened the pipe so that it provided the shrapnel. The detonator was a short length of crimped safety fuse taped to usually two or more matches. Pipe bombs were difficult to identify and could be transported as part of a plumber’s tool kit or a delivery to a shop or client. For devices left at targets, time delay fuses were built in. In the British L Delay detonator, a thin length of wire stretched under pressure until it snapped and dropped the striker to hit the detonator. In the Number 10 Time Pencil used by EOKA, a small glass capsule of crushed acid nibbled through the wire under tension.