Participation of child soldiers on the Iranian front (top left); Iranian soldier wearing a gas mask (top right); Port quarter view of USS Stark listing to port after being mistakenly struck by an Iraqi warplane (middle left); Pro-Iraq PMOI forces killed in Operation Mersad (middle right); Iraqi prisoners of war after the re-capture of Khorramshahr by Iranians (below left); ZU-23-2 being used by the Iranian Army (below right).

Iran’s liberation of Khorramshahr in May 1982 drove the final nail in the coffin of the Iraqi invasion. Some 12,000 Iraqis became prisoners of war.

Until September 1981, when the Iraqis were forced out of Abadan in some disorder after some clever manoeuvring by the Iranians that encouraged them to weaken their defences, the war fronts had been generally quiet, with occasional artillery shelling of each side’s entrenched positions. But the Iraqi withdrawal from Abadan, as well as encouraging the Iranian military and people, meant that the roads around Abadan became free again for the movement of troops and supplies, creating possibilities for new Iranian offensives.

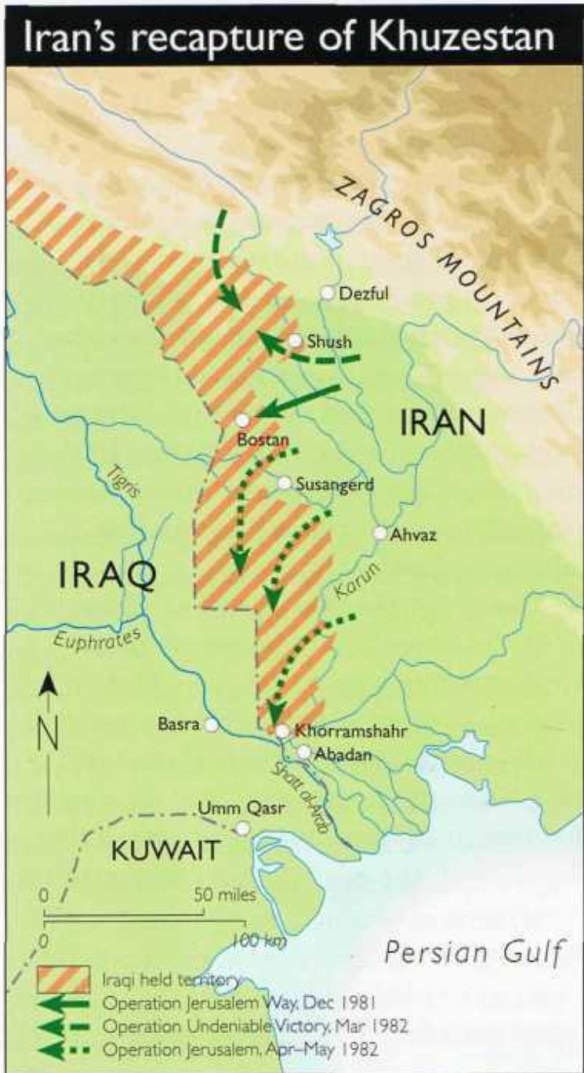

Despite the onset of the rainy season, the Iranians launched a surprise offensive on 29 November from Susangerd, north-westward toward Bostan. About 13,000 Iranian troops took part; more than a third of them were Sepah, and this was the first time that what became known as `human wave’ attacks were used. Despite rain and mud, Sepah troops surged forward so enthusiastically that regular commanders had to abandon their plan for a preparatory artillery barrage for fear of hitting their own people. Bostan was recaptured and the Iraqis retreated several miles back towards the border. The Iranians carried out a further successful operation (al-Fajr – `Dawn’) in December near Qasr-e Shirin, recovering more territory.

By mid-March 1982 the Iranians had built up the strength of their forces in the area around Dezful and Shush to somewhere around 100,000, including 40,000 Sepah and 30,000 Basij volunteers – the latter mainly young, with only rudimentary training and some unarmed, or carrying Kalashnikov assault rifles captured from the Iraqis. On 22 March they attacked in the first phase of what was called Operation Fatah or Fath ol-Mobin (Victory), initially with waves of Sepah and Basij armed with rocket-propelled grenades [RPGs] and rifles, following up with regular troops, targeting Iraqi conscript units first where possible, to try to force them back and expose the flanks of more experienced troop formations. Before the main ground forces went in, commando troops were carried behind the Iraqi lines by Chinook helicopters to destroy Iraqi artillery. The Iranians suffered heavy casualties but their tactics were successful, pushing the Iraqis back and beginning to encircle them. Iraqi air strikes had some success in stemming the Iranian advance in one area, around Chenaneh, but large numbers of Iranian F-4s and F-5s, plus helicopter gunships, were also in action against Iraqi tanks and troops. The Iranian offensive lasted a week, and by the time it ended more than 300 Iraqi tanks and other armoured vehicles had been destroyed, and a similar or larger number had been captured, along with more than 15,000 Iraqi prisoners. When the Iraqis managed to stabilize their front by bringing in reinforcements, their positions were back within 5-10 miles of the border.

Some of the Basij volunteers that fought in the war were thirteen or even younger (though there were also older men, in their sixties and seventies) and some of them lied about their age to be allowed up to the front with their friends. One spoke to an aid worker in an Iraqi prisoner-of-war camp after he had been captured about his motive for joining up:

I am not very religious so I don’t know much about the subject. It’s true that martyrdom is important to Shi`ites – we all learn about the Emams and how they died – but I didn’t go to war to die for Islam. I went to defend Iran and I think most of my friends went for the same reason.

Another boy, asked a similar question, gave a more conventional religious answer, talking about martyrdom and dying for Islam, but even he put that reason second, saying first: `All Iranians came to war to defend their country from the Iraqi invasion. That is a normal thing to do. I think British people did the same in the Second World War against Germany.’

This is another misunderstanding – or failure of understanding – about the Iran-Iraq War. A lot was written at the time about the so-called fanaticism of the Iranian human wave attacks, about the way the Iranians were whipped into a frenzy by the mullahs, about young men anxious to be martyrs, and so on. But most Iranian veterans speak in this same sober way about their experience and their motivation. We should not need to displace the fact of their bravery into categories like fanaticism and martyrdom in order to comprehend it. Newsreel images from the time show soldiers being harangued by mullahs, chanting religious slogans and beating their chests rhythmically (as in the Ashura rituals), but they also show scared young men preparing for the fighting with determination despite their fear. They were rather like the young men of Kitchener’s army preparing for similar infantry attacks against prepared defences on the Somme in 1916 or elsewhere; with much the same patriotism and commitment to their comrades, and encouraged to volunteer by much the same wish for adventure. They were exploited in much the same way by their governments and generals, because governments and generals need naive young men and boys to fight for them – older men tend to be more cautious.

Another boy said:

It was a game for us . . . We didn’t understand the words `patriotism’ or `martyrdom’, or at least I didn’t. It was just an exciting game and a chance to prove to your friends that you’d grown up and were no longer a child. But we were really only children.

He was asked by the same aid worker whether it was right for Iran to use such young boys in the war:

I am not sure, but it was difficult to stop them. And anyway, the boys who attacked the Iraqis were a very important weapon for the army, because they had no fear. We captured many positions from the Iraqis because they became afraid when they saw young boys running towards them shouting and screaming. Imagine how you would feel. Lots of boys were killed, but by that stage you were running and couldn’t stop, so you just carried on until you were shot yourself or reached the lines.

Another, interviewed separately, years later, recalled his time as a prisoner in Mosul in 1985-6:

When the war started I was sixteen years old. I gave up school and studying and went to the front, but I didn’t last long and after less than six months I was captured. I was there in the camp without anything to do, so started studying. We didn’t have any books – just an English dictionary which was passed around between at least twenty people, and this was the way all of us learned English. I remember that on any given day I could only use the dictionary for an hour – it was torn badly and the pages were in the wrong order. One day, I will never forget, the United Nations Red Cross staff came and asked me what I needed – I replied, a dictionary. But I realized I could only use this dictionary for an hour a day, so another idea occurred to me – to start chatting with the Iraqi guards and learn Arabic. Now, since my release, I can speak English, Arabic and some French.

The commander in Operation Fatah was a young regular army officer who had been promoted recently to chief of staff – General Ali Sayad Shirazi. Shirazi had proved his revolutionary credentials by demonstrating against the Shah, and being demoted and imprisoned before the revolution, and so despite his youth was a natural choice for the revolutionary leadership at a time when they distrusted senior officers who had been promoted by the Shah. Sayad Shirazi was a talented commander and proved his abilities in several later battles also, bridging the gap between the regulars and the Sepah and coordinating their efforts to enable them to make effective attacks together.

The outcome of Operation Fatah was an important encouragement to the Iranians, and appeared to endorse their tactical innovations – particularly the human wave attacks favoured by the Sepah and Basij. A little more than a month later, on 30 April, a further offensive (codenamed Qods/Beit al-Moqaddas – Jerusalem) using similar tactics began, this time towards Shalamcheh. Despite Iraqi counter-attacks the Iranians were successful, and Saddam was again forced to withdraw troops rather than see them encircled and cut off. The Iranians reached Shalamcheh on 9 May – one effect was to put greater pressure on the Iraqi garrison of Khorramshahr, to the south. In the second phase, the Iranians attacked Khorramshahr itself on the night of 22-3 May and within a day had retaken the city, capturing 12,000 Iraqis.

The recapture of Khorramshahr was a major morale victory for the Iranian military and the Iranian people, as its loss had been a humiliation. For Iraq, following on from the previous defeats, it was a moment of crisis – there was unrest and rioting in several Shi`a-dominated towns and cities in southern Iraq. Many observers, within and beyond the region, expected that Saddam would be replaced as Iraqi leader. Instead, Saddam intensified the repression of Shi`a dissidents, reshuffled the top leadership in the country under him (to include more Shi`as, among other changes), offered peace again to Iran, and on 20 June began a withdrawal to the pre-war borders. The withdrawal was completed by the end of the month, but despite Saddam’s announcements the Iraqis stayed in occupation of some Iranian territory. Saddam may also, as a provocation, have ordered the assassination of the Israeli ambassador in London, Shlomo Argov. Argov was shot in the head and permanently paralysed on 3 June 1982; the assassins belonged to Abu Nidal’s organization, which had split from Yasser Arafat’s PLO in 1974 – but one of them was also a colonel in Iraqi intelligence. Although the main, more deep-seated reasons for the invasion were a more important motivation (principally, the desire to remove the PLO from Lebanon), the assassination attempt was used by Israel to justify its invasion of Lebanon on 6 June. When Saddam offered peace again at the end of June, in parallel with the withdrawal to the pre-war borders, he also suggested that this be done so that both Iran and Iraq could use their forces against the Israeli invasion of Lebanon.