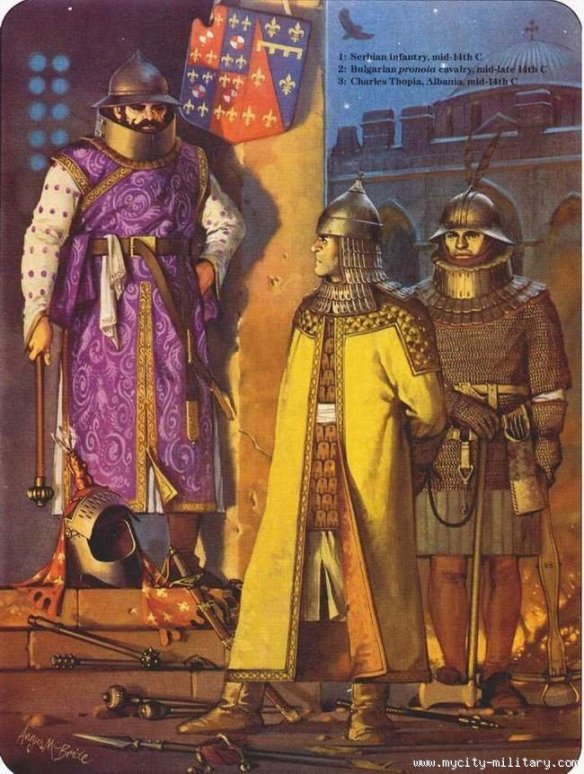

1. Serbian infantry, mid-14th century This man is in almost all aspects identical to the heavy infantry of Italy. His separate mail-covered gauntlets may, in fact, have been a Byzantine and Balkan fashion that had spread to Italy early in the 14th century. Only his massive splinted gorget neck and shoulder protection is different. Such pieces of armour appear quite suddenly in 14th-century Balkan art, and though they are sometimes worn by infidel or alien figures in Italian illustrations they are otherwise rarely seen anywhere else except 14th century Spain. A connection may be possible via the mercenary Catalan Grand Company and Spanish-ruled southern Italy, but it is not known in what direction such hypothetical influence flowed. (Sources: helmet, perhaps of German origin, Milit. Mus., Belgrade; warrior saints, Serbian wall-paintings, 1333—1371, in situ Chapel of St. Nichola Sopocani Monast., Church Psaca, Monastery Church Decani, Church Lesnovo, Yugoslavia; Pride, carved capital, early i4th C, in situ Doge’s Palace, Venice; St. George, early i4th C, wall-painting, in situ Church of Panaghia Kera, Kritsa, Crete; Hungarian manuscript, 1325-50, Pierpont Morgan Lib. M.360-11, New York.)

2. (sredina) Bulgarian pronoia cavalryman, mid-late 14th century The contrast between this warrior and the Serbian infantryman highlights the differing military traditions of the eastern and western Balkans. He is not only very similar to a late Byzantine warrior but his equipment and costume both show considerable Turkish or Mongol influence. This is particularly apparent in his long coat, his reliance on lamellar armour, and the bells on his spear-shaft. The collection of maces may be captured symbols of rank. (Sources: helmet from Khalkhis, Ottoman or late Byzantine, Ethnolog. Mus., Athens; maces from Stara Zagora region, I3th-i4th C, Kazanlik Mus., Bulgaria; Manasses Chronicle, Bulgarian 1344-5, Vat. Lib. Cod. Slav 2, Rome; Psalter, Bulgarian or Serbian £-.1370, Bavarian State Lib. Cod. Slav 4, Munich; wall-painting, c. 1355, in situ Zemen Monastery, Bulagaria; warrior saint Serbian wall-painting, c. 1307, in situ Ch. of Our Lady of Leviska, Prizren.)

3. Charles Thopia(U nasoj literaturi: Karlo Topija), Albania, mid-14th century Although no picture survives of Charles Thopia, lord of Kruja and Petrala, a fine carved relief does illustrate his coat-of-arms and crest. Here his tunic, which is remarkably similar to early Ottoman court costume, is taken from a similarly-dated painting of

Peter Brajan, the Jupan or governor of a neighbouring region of Bosnia. Like the Serbian infantryman he is protected by a brimmed helmet and an even more massive gorget or bevor. (Sources: bronze-covered lead mace from Luk, Archaeol. Mus., Split; bas-relief showing armourial bearing of Charles Thopia, in situ Church of St. John Vladimir, Elbasan, Albania; Peter Brajan, Serbian wall-painting £.1335, in situ Church Karan, Yugoslavia; warrior saint wall-painting 1338—50, in situ Monastery Church, Decani, Yugoslavia; Loyal Address from City of Prato to King Robert of Naples, 1335-40, British Lib. Ms. E. IX, London; barbarian warrior in St. Martin renouncing the sword, wall-painting by Simone Martini, c. 1317, in situ Montefiore Chapel, Lower Church of St. Francis, Assisi.)

1: Serbian auxiliary, 14th century

The frescoes of c. 1309-14 on which this figure is based demonstrate that 14th century Serbian equip¬ment, like 14th century Bulgarian, differed little from that of Byzantium, though the Serbs, whilst making some use of the triangular shield by then preferred in the Empire, continued to favour the almond-shaped variety. Their preferred weapon combination appears to have been lance (still often wielded overarm), sword, mace and composite bow. The fact that Serbian armoured cavalry of the 13th and 14th centuries were prepared to fight as horse-archers is confirmed bv Kantakouzenos’ military

memoirs and pictures in Serbian manuscripts. Cer¬tainly the Serbs in the Nicaean army at the Battle of Pelagonia in 1259 were horse-archers.

2: Bulgarian auxiliary, c. 1345

Pictorial sources demonstrate that the similarity be¬tween Bulgarian and Byzantine equipment persisted until Bulgaria fell to the Ottoman Turks at the end of the 14th century. Bulgarian costume, however, re¬mained distinctly Balkan. The source for this figure is the Manasses Codex made for Tsar Ivan Alexander (1331—65), the illustrations of which indicate that the long gown often concealed light body-armour (Bul¬garian mail or lamellar corselets often reaching only to the waist or hips). All Bulgarian cavalrymen were customarily armed with a composite bow, though their heavy cavalry at least also carried a lance.

3: Serbian knight, 15th century

Under constant pressure from the Ottomans throughout the second half of the 14th century, Serbia began to import a growing volume of its arms from the West, in particular from Venice and Lombardy. By the 15th century better-equipped Serbs had become indistinguishable from their Italian counterparts, except in retaining a shield (probably in response to the Ottomans’ dependence on archery). Ironically contingents of Serbian heavy cavalry consequently appeared in most Ottoman field armies during the first half of the 15th century, becoming famous for the effectiveness of their close-order charge . A 1,500-strong Serbian contingent even attended the siege of Constantinople in 1453.

The Territories before the Battle. You can see Chernomen marked with an X.

Victory for Murad I in the first pitched battle for the Turks in Europe. He defeated the Serbians under King Vukashin by the Maritza west of Adrianople. The Serbs had Bulgar allies. The Byzantine emperor John V was in the west seeking aid. The Turkish force was smaller but surprised the Serbs, who broke and fled, the end of a powerful medieval Serbia and of the independent Serbian principality of Serres. Macedonia fell to the Turks while Byzantium and Bulgaria became Murad’s clients. Constantinople was surrounded by Turkish territory.

It was not until the reigns of Orkhān and Murād I (1362-1389) that Ottoman armies reorganized to take better advantage of infantry, and there is little doubt that this was the reason for the increased military success in capturing more lands and facing new enemies. In particular, Murād I used a mixed array of ordinary and elite infantry troops and mounted archers and more traditional cavalry to defeat opposing Serbians at the Battle of Maritsa in 1371 and crusaders at the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396. In both, Turkish infantry- the first ranks composed of ordinary soldiers and the rear of elite ones-were used to lure opposing heavy cavalry into a trap between two flanks of their own lighter, more maneuverable cavalry forces where the now halted and exhausted attackers were immobilized and defeated.

After the death of Stephan Uros in 1355, the Serbian kingdom began to decline. The vast territories in Macedonia and Greece were divided between different rulers from the central dynasty. Some of those considered themselves so independent from the main hierarchy that they called themselves kings. This was the case with the two brothers Vukašin and Uglješa. They both controlled territories in today’s Macedonia. Vukašin claimed to be “The king of all Serbians and Greeks” – in opposition to his brother.

In 1371 the army was ready. However, there is no hard evidence about the size of their army. It’s considered to be anywhere between 20,000 to 70,000. Based on the land they held and the tactic they employed, however, a smaller number is more likely.

The Ottoman force for the battle was significantly smaller, but the exact number can again be debated. Their contemporary historical sources say they were no more than some 800 strong. We could possibly put their numbers at around half of what the Serbian alliance had.

The difference which decided the battle’s outcome was more the quality than the quantity. The entire Ottoman force consisted of seasoned warriors, who had survived numerous battles, sieges, and raids. On the contrary, the Serbian force consisted of an undisciplined rebel army and a small amount of cavalry.

Furthermore, it was logical that the Ottoman ghazis had superior experience. After all, they were in constant clashes with the resistance of the Balkan people. The Ottomans probably had a smaller but far better army.

Confident in their bigger force, the two brothers began their march. They looked forward to expelling the Ottomans from Erdine and stopping their expansion. Their plan was to go down the stream of the river Maritsa and lead a surprise attack. Lala Shahin, however, knew what was going on. He also had extensive experience fighting in a rough terrain and organizing ambushes.

Considering his tactical advantage, he took measures in order to stop the Serbians’ advancement. The Ottoman leader sent trackers to scout the region. The Serbians were overly confident, and never bothered to do that.

Thus, the Lala Shahin waited for the right moment to rout the marching rebels. His chance came in the early morning hours of the 26th of September. The Serbians had made their camp near the Maritsa and had made one final crucial mistake. They decided to celebrate their future victory and held a feast. By the morning, the camp largely unguarded and many of the men were drunk.

The force of the Ottoman leader Lala Shahin entered the camp in the morning. His men took their knives out and began slaughtering their sleeping enemies. In the Massacre that followed the two Serbian leaders were mercilessly killed. Whoever did not die from the Ottoman blades drowned in the river of Maritsa, in an attempt to escape.

Lazar I

(d. 1389)

Serbian ruler Since at least the 19th century Serbs have memorialized the defeat and death of Lazar I at the Battle of Kosovo in (1389) as an event of central significance in the nation’s history. The defeat of Lazar’s forces by the army of Ottoman sultan Murād I is frequently used to mark the end of independent, medieval Serbia and the beginning of Turkish rule. Popular songs and poems dating back to the 16th century or earlier recount the martyrdom of Lazar, who according to tradition was visited by an angel the night before the battle and offered a choice between a heavenly and an earthly kingdom. Choosing the former he was then betrayed by a rival prince secretly allied to Murād. Some versions of the story include a Serb nobleman who demonstrated his true loyalty by sneaking into the Ottoman camp and killing the sultan before the battle. The traitorous prince is commonly identified as Vuk Branković and the loyal noble as Miloš Obilić, both supposedly sons-in-law of Lazar and rivals for his attention. Nationalist writers have used this tale of divine selection, betrayal, loyalty, and deceit to symbolize the historical destiny of Serbia and explain its subsequent incorporation into the Ottoman Empire: 1299-1453.

Between the 12th and early 14th centuries Serbia was united under the Nemanyich dynasty, which consolidated Serb control over much of the central Balkans. The last ruler of the dynasty, Czar Stephan Dušan (r. 1331-55), built a short-lived Serbian empire, extending his control over Albania, Macedonia, and much of Greece, and promoting the elevation of the archbishop of Ipek to the position of patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Following Dušan’s death his son Uros proved unable to maintain his father’s legacy, and real authority quickly slipped into the hands of a number of regional lords. In 1371 one of his supporters, Vukašin, was killed at the head of a large Serb army in battle with the Turks on the Maritsa River. Uros died two months later, ending the Nemanyich dynasty and with it any real hope for the revival of the Serb empire. The country disintegrated into a number of independent but weak principalities, each vying for territorial control.

The strongest of the remaining Serb rulers was Lazar Hrebeljanovic of Kruševac. In 1374 a gathering of Serb nobles at Ipek recognized him as their leader. Lazar consolidated his position by concluding marriage alliances with the leading nobles in Kosovo and Montenegro, Vuk Branković and Gjergj Balsha. He also developed close relations with King Tvrtko of Bosnia, the strongest ruler in the region. To further bolster his position, he cultivated the support of the Serb patriarch by granting the church additional lands and founding the monastery of Ravanica. Though successful in establishing and defending his role as the leading prince in Serbia, Lazar was unable to reunite a Serb state.

As for other Serb rulers, Lazar’s relations with the Ottoman Turks were complicated. In the 14th century Ottoman influence in the Balkans was growing rapidly, capitalizing on the internal disorder and decline of the Byzantine, Bulgarian, and Serbian empires. Numerous Christian rulers entered into alliance with the Turks or accepted vassalage in return for Ottoman support in their struggle with neighboring princes. Christian forces were commonly found fighting on the sultan’s campaigns and Turkish soldiers were occasionally lent to Christian princes. Throughout, the Ottomans steadily gained territory and strength, emerging as the leading power of the region.

In 1386 Murād seized Niš from Lazar and two years later raided Bosnia. The following spring the Ottomans prepared to occupy Lazar’s possessions in Kosovo as a prelude to an attack on Bosnia. Lazar called on the assistance of Tvrtko, who provided a large force, as did Lazar’s son-in-law, Vuk Branković. The two armies met at Kosovo Polje on June 15, 1389. Both armies suffered heavy casualties and Lazar and Murād died in the battle, at the end of which Lazar’s army fled. Though the Ottoman army controlled the field, Murād’s son Bayezid I abandoned the campaign in the Balkans and led the remaining Turkish forces against his brother in Anatolia in order to secure his succession to the throne.

There is no direct historical evidence supporting the details of the popular legends associated with the Battle of Kosovo. The identification of Vuk Branković as Murad’s secret ally in the battle and the betrayer of Lazar is unlikely given his subsequent, firm resistance to the Ottoman advances in the region. Similarly the suggestion that Lazar’s defeat marked the end of the medieval Serb empire and the beginning of Ottoman rule fails to account for the dissension of the Serb nobles following Dušan’s death, their continued independence in the half-century following the battle, and their frequent cooperation with the Turks throughout the period.

Though it was likely not the epic confrontation described in Serb folk traditions, Lazar’s defeat in the Battle of Kosovo, as the battle on the Maritsa in 1371, marks the gradual decline of Serb resistance to Ottoman expansion in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. In both cases, the Serbs suffered large casualties. After the battles Serb princes were divided in their reaction to Ottoman victory, with some continuing to resist and others seeking to accommodate the Turks.

Further reading: Fine, John. The Late Medieval Balkans. Detroit: Michigan University Press, 1987; Malcolm, Noel. Kosovo: A Short History. New York: New York University Press, 1998; Sugar, Peter. Southeast Europe under Ottoman Rule, 1354-1804. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977.