In the battle of Slim River on 7 January 1942, some 30 Japanese tanks and a motorized infantry battalion completed the virtual destruction of the 11th Indian Infantry Division.

Japanese Armor at Slim River

The Japanese used two types of tanks at the Slim River battle. The main medium tank used was the Type 89 I-Go, which was the most common Japanese medium tank throughout the early part of the Pacific war. The light tanks used were Type 95 Ha-Gos, which were encountered by Allied forces throughout the entire war.

The Type 89 I-Go was an older design that was first introduced in 1934. Weighing 15 tons, its armor was only 17mm at its thickest. The tank had a maximum speed of 16 mph, due to its being relatively underpowered. The 57-mm gun was a good infantry support weapon; however, there was no coaxial machine gun – the turret machine gun faced out of the turret rear. In addition, there was a hull machine gun. The Type 89 did carry a large amount of ammunition: 100 57- mm rounds and 2,800 rounds of machine gun ammunition. It was cramped for its crew of five men, and visibility from it was poor. There was no radio to communicate with other vehicles, communication being done by flags or shouted orders. The Type 89 had an unrefueled range of 110 miles.

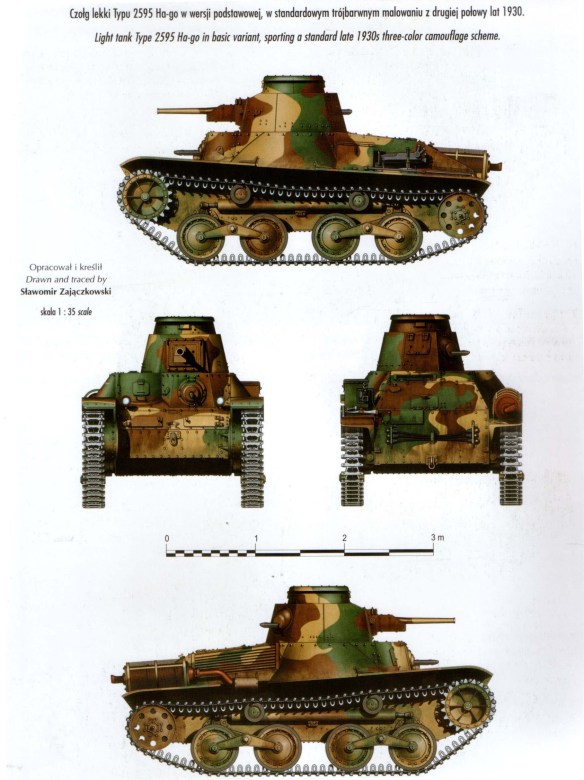

The Type 95 Ha-Go light tank was a slightly newer design that had some of the same problems of the Type 89 as well as many of its own. The 7.4-ton tank had even thinner armor than the Type 89 (16mm). It was faster than the Type 89 and could achieve its maximum speed of 28 mph. It was armed with a 37-mm gun, as well as two machine guns in a similar arrangement to the Type 89. However, the three-man crew could not operate all the weapons at once. The commander was particularly overtaxed, having to load and fire the main gun or turret machine gun, as well as command the tank. The Type 95 also had an operational radius of about 130 miles.

The Battle

“On this first day of the new year, I breathe the air of the South,” Tomoyuki Yamashita wrote in his diary as the pivotal year of 1942 opened on an IJA in motion across Southeast Asia. “I was up at 5 am and it was already hot. I must put away recollections of the past. My duty is half done, although success is still a problem. The future of my country is now as safe as if we were based on a great mountain. However, I would like to achieve my plan without killing too many of the enemy.”

Writing of the Japanese tactical plan in the Malay Peninsula as 1942 began, Masanobu Tsuji could have been speaking of the Japanese strategic perspective on the entire operation from Sumatra to Luzon when he observed that “the 5th Division pushed southward as fast as possible in order to give the enemy no time to develop new defensive positions.”

However, on New Year’s Eve, it was Tsuji who was scrambling for a defensive position. As the bridge work on the Perak River was ongoing, the spearhead of Japanese 5th Division infantry troops, specifically Major General Saubro Kawamura’s 9th Brigade, including the 41st Infantry Regiment, continued cycling southward on the highway. They had penetrated another 40 miles southward toward the capital of British Malaya at Kuala Lumpur, and had reached a point north of the city of Kampar by December 30. Tsuji and a couple of aides had “requisitioned” an automobile in Ipoh and had decided to drive south “to share a glass of wine with the troops in the line to celebrate the New Year on the battlefield.”

As they approached Kampar, they came under fire from British artillery in the surrounding hills. The 11th Indian Infantry Division, temporarily commanded by Major General Archie Paris (of the 12th Indian Infantry Brigade), had chosen Kampar to erect the sort of defensive barrier the defenders should probably have established on the Perak. Tsuji arrived just as the battle was being joined, and apparently he left shortly thereafter, as Kawamura’s troops undertook a bloody fixed battle that halted the Japanese advance for four days.

At exactly the same time that the battle of Kampar was taking place, Tsuji’s boss, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the commander of the 25th Army, was implementing a daring tactical move with which his planning officer, Tsuji, fervently disagreed. Indeed, it would result in a brief tantrum of gekokujo from Tsuji that threatened to mar the amazing precision and achievement of the operation thus far.

Yamashita’s plan – brilliant in retrospect as are all unorthodox plans that succeed – was to circle behind the British defenses. This plan, conceived before the battle of Kampar, was to outflank Archie Paris’s 11th Division line, which ran for roughly 30 miles, from Kampar to Telok Anson (now Teluk Intan), where the meandering Perak River flows into the Straits of Malacca. Using the motorized landing boats from the Singora landings that had been brought up for the Perak River crossing, as well as others captured along the way, Yamashita would land 1,500 men, mainly from the 5th Division’s 11th Regiment, behind the enemy’s lines, south of the mouth of the Perak.

Tsuji complained that he was sure the men would be intercepted by British air or naval assets, and not only the men, but vessels necessary for the eventual landings on Singapore’s fortress island, would be lost. In his memoirs, Tsuji writes dramatically that as he watched the regimental commander walk away to undertake the operation, “I could see the shadow of death on his back.”

The contingent put to sea late on December 30 from Lumut, and landed on January 4 near Sungkai. While en route, they were strafed once, but only once, by British aircraft. Realizing that they were sitting ducks for a determined air attack, they expected to be finished off at any moment, but the British never returned. The “shadow of death” that Tsuji had seen was merely an apparition. Yamashita’s plan worked.

In the meantime, Kawamura’s spearhead, reinforced by replacements rushing south from the Perak River crossing, were able to claw their way through the 11th Indian Division positions in Kampar and the surrounding hills. The 11th suffered severe casualties in the battle, but Japanese 5th Army’s 41st Infantry Regiment, which bore the brunt of the unexpectedly difficult fight, had to be withdrawn from combat to regroup.

Despite the damage inflicted to the Japanese at Kampar, this battle had been conceived as a delaying action, not as a counterattack, and in the aftermath, the British executed a further withdrawal, this time to the town of Slim River (now Sungai Slim), near the river of the same name. Meanwhile, any small measure of satisfaction that might have been gained from the successful holding action was offset for the British by the discovery of Japanese troops in their rear along the coast. This only served to hasten the withdrawal and add to the confusion.

By January 5th, 1942, the British were in full retreat from northern Malaya. They had suffered through a month of disastrous engagements, forced out of position after position by Japanese envelopments. On more than one occasion, the road bound British units had to attack through Japanese roadblocks to be able to retreat. This unbroken string of disasters had left its mark on all the British units engaged, particularly the 11th Indian Division, which had done much of the fighting. The men who were to occupy the defenses at Slim River were punch-drunk with fatigue and suffering the low morale of constant defeat.

The Japanese, on the other hand, were on a roll. Although fewer in aggregate numbers, they were able to more effectively mass their combat power along the maneuver corridors. Their tactics were simple but effective. Their advance guard, a reinforced battalion of combined arms elements, including infantry (often mounted on bicycles), armor, and engineers would advance down the maneuver corridor until they made contact. If not able to immediately fight through, the Japanese would launch battalion- or regimental-sized infantry envelopments to get behind the British positions, cut their lines of communications, and attack them on their unprotected flanks. The key to the Japanese success was their ability to sustain momentum and keep the pressure on the British.

By January 4th, the 12th and 28th Brigades of the 11th Indian Division moved into positions forward of Trolak and extending in depth back to the vicinity of the Slim River bridge. The division commander, General Paris, hoped to forestall the previous effects of shallow Japanese envelopments by lacing his troops in depth. To quote him:

“In this country, there is one and only one tactical feature that matters – the roads. I am sure the answer is to hold the roads in real depth.”

This statement is not as unreasonable as it may first appear.

Although the Japanese logistical tail was considerably shorter than that of the British, it still had to use the road system to sustain its force. General Paris reasoned that any Japanese attempt to conduct a short envelopment through the jungle, as previously experienced, could be counterattacked by the brigade in depth. The maneuver corridor did not present much more than a single battalion’s frontage, even considering outposts and security elements placed up to a kilometer into the jungle on either side. Instead of trying to extend their forces into the bush to confront the Japanese while they were infiltrating, the British would commit reserves to counterattack them when they appeared. This would keep their forces mobile along the road system.

The 12th Brigade took up forward positions with its battalions arrayed in depth, beginning in the vicinity of mile post 60 and extending back to mile post 64 (see map, following page). Two battalions of the Indian Army occupied the forward positions; the 4/19th Hyderabad occupied the initial outpost position and the 5/2nd Punjabi occupied the main defense about a mile back.

A third British battalion, the Argyl and Sutherland Highlanders, was positioned in the vicinity of Trolak village, where the jungle began to open out onto an estate road. The brigade reserve, the 5/14th Punjabis, was positioned at Kampong Slim with the mission of being prepared to move to a blocking position one mile south of Trolak near mile post 65. The 28th Brigade’s positions were south of the 12th along the maneuver corridor, and were arrayed as single battalions in depth, much like the 12th Brigade. However, on the early morning of January 7th, the brigade had still not occupied the positions, having been instructed by General Paris to rest and reorganize. The British infantry units had 12.7-mm antitank rifles and 40-mm antitank guns. The AT rifles were only marginally effective. The AT guns would penetrate any Japanese tank with ease.

A key to the defensive scheme would be the defenses and obstacles along the main road. The British should have had enough time to construct defenses that would have precluded a quick Japanese breakthrough. The British were also in the process of preparing to demolish numerous bridges along the main road. However, several factors were to conspire against them.

The first factor was fatigue. Their forces were tired, to the point where they didn’t do a good terrain analysis when setting in their defense. There were many sections of the old highway running parallel to the newer sections that had been straightened. These old sections ran beside the main road through the jungle and were excellent avenues of approach. There were also numerous side roads through the rubber plantations, and many of these roads were overlooked. Others were noted, but did not have sufficient forces allocated to them.

Secondly, the British units had all suffered numerous casualties. Many of their formations were under new and more junior leadership. These leaders were trying to cope with the monumental task of reorganizing their stricken units while conducting defensive preparations, and they were suffering from fatigue as much as (if not more so) than their troops.

Another critical British deficiency was communications equipment. The 11th Indian Division had lost a great deal of its signal equipment in the month-long retreat prior to the Slim River battle. As a result, there was not sufficient communications equipment to lay commo wire between the brigades. This lack of communications, combined with fatigue, also prevented the British artillery from laying in and registering its batteries to support the infantry positions. Lastly, the Japanese had complete mastery of the air. This precluded the British from moving up their supplies in daylight and severely limited the extent of their defensive preparation.

All of these factors combined to rob the British of their opportunity to build a cohesive defense. They had sufficient barrier material, in the form of mines, concrete blocks, and barbed wire to construct an effective obstacle system in depth, but at the time of the Japanese attack, only a fraction of it had been brought forward. In the location where the Japanese actually broke through, there were only 40 AT mines and a few concrete blocks emplaced when the Japanese attacked.

On the afternoon of the 5th, the British 5/16th (the covering force) withdrew, and soon afterward the advance guard of the Japanese 42nd Regiment, 5th Infantry Division, made contact with the forward elements of the Hyderabad battalion. The Japanese probed the Hyderabads’ forward positions and were repulsed. The Japanese advanced guard commander, Colonel Ando, decided to wait for tanks and other supporting troops. The 6th of January was spent by the Japanese reconnoitering the British defenses and preparing for their usual infiltration along the British flanks.

Major Shimada, the commander of the Japanese tank unit attached to the 42nd Infantry (a company plus of 17 medium and 3 light tanks from the organic tank battalion of the Japanese 5th Infantry Division) implored Colonel Ando to be allowed to attack straight down the road. Ando was at first skeptical, but finally acquiesced, reasoning that if the tank attack failed, the infiltration could still continue. The Japanese tank company, with an attached infantry company and engineer platoon in trucks, was set to begin the assault at 0330 the next morning.

The Japanese attack began with artillery and mortar concentrations falling on the 4/19th Hyderabad’s forward positions, while at the same time infantry units assaulted the forward positions of the Hyderabads, and engineers cleared the first antitank obstacles along the road. At approximately 0400, the Japanese armored column started forward, crewmembers initially ground-guiding their vehicles through the British obstacle.

The Hyderabads had no antitank guns, but did manage to call artillery fire on the Japanese, which knocked out one tank. The rest of the Japanese column swept through the breach and continued down the road to the next battalion position. Behind them, the remainder of the 3rd Battalion, 42nd Infantry, completed the destruction of the Hyderabad battalion, leaving only disorganized and bypassed elements to be mopped up later.

The Japanese column moved on. By 0430, it had reached the main defensive belt of the 5/2nd Punjabi battalion. The lead tank hit a mine and was disabled, and the remainder of the column stacked up behind the disabled vehicle almost bumper to bumper. The Punjabis attempted to knock out the Japanese tanks with Molotov cocktails and 12.7-mm antitank rifles, but were largely stopped by a heavy volume of fire from the Japanese tanks and infan try. At this point, the Japanese found one of the unguarded loop roads that paralleled the main road and took it, bypassing the Punjabi defenses and taking them in the flank. The Punjabis’ defense collapsed into a series of small units fighting where they stood or trying to escape. The Japanese armor continued on, leaving the tireless 3d Battalion, 42nd Infantry, and other elements of the Japanese advance guard to complete the destruction of the Punjabis.

Unfortunately for the British, this was the last prepared defensive position facing the Japanese. The Punjabis had emplaced only a single small minefield. In spite of this, they somehow managed to hold the Japanese for almost an hour, taking heavy casualties from the tanks’ fire, before the Japanese found another loop road and were off again. It was about 0600; the Japanese were exploiting like broken-field runners. Almost 1,000 British and Indian soldiers were dead, prisoners or fugitives in small groups heading south along the edge of the jungle.