May 5, 1864

In April 1864 the new shallow-draft Confederate ironclad ram Albemarle (with two 6.4-inch rifled guns) played the key role in the capture of Plymouth, North Carolina. The attack on the Union base, begun on April 17 by 7,000 Confederate troops under Brigadier General Robert F. Hoke, had failed in large part thanks to gunfire support provided by Union gunboats on the Roanoke River. Early on April 19, however, the Albemarle, captained by Commander James W. Cooke, appeared and attacked the Union wooden gunboats Miami (with one 6.4-inch Parrott rifled gun, six IX-inch smoothbore Dahlgrens, and one 24-pounder boat howitzer) and Southfeld (with one 6.4-inch Parrott rifle and five IX-inch Dahlgrens). With Union shot bouncing harmlessly off its plated sides, the Albemarle rammed and sank the Southfeld. The commander of the Southfeld, Lieutenant Commander Charles W. Flusser, was killed; 11 other Union seamen were wounded, and 8 were taken prisoner. The Albemarle lost 1 man, killed by a pistol shot.

The Miami and other Union ships then withdrew from the river to watch the ram from a distance. The Albemarle now controlled the water approaches to Plymouth. Its guns and the sharpshooters aboard the Confederate steamer Cotton Plant enabled the more numerous Confederate infantry to take Plymouth on April 20.

Following the loss of Plymouth, Captain Melancton Smith, commanding Union naval forces in the North Carolina sounds, assembled additional ships below Portsmouth. His squadron consisted of the double-ender gunboats Mattabesett (the flagship), Sassacus, Wyalusing, and Miami; the converted ferryboat Commodore Hull; and the Ceres, Whitehead, and Isaac N. Seymour.

On the afternoon of May 5 another engagement occurred at the head of Albemarle Sound, off the mouth of the Roanoke River, in consequence of Cooke’s plan to convoy the Cotton Plant to the Alligator River. On exiting the Roanoke, the Albemarle, which was accompanied by the ex-Union steamer Bombshell, was met by six Union gunboats under Lieutenant Commander F. A. Roe in the Sassacus. The Bombshell surrendered early in the action, and the Cotton Plant withdrew back up the Roanoke, but the Albemarle continued the action alone.

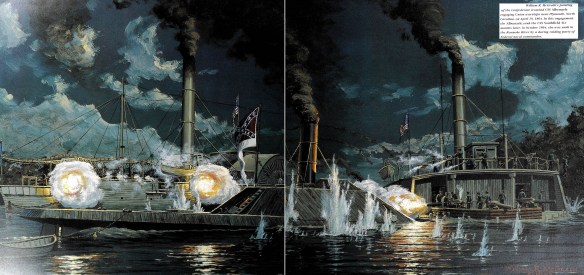

USS Sassacus ramming CSS Albemarle

Making between 10 and 11 knots, the Sassacus rammed the Albemarle on its starboard side just abaft the casemate. Simultaneously, the ram fired a rifle bolt that passed completely through the Union ship. Meanwhile, crewmen on the Sassacus tried to throw hand grenades down the deck hatch of the ram, and both sides traded rifle fire. Another Confederate rifle round then smashed into the starboard boiler of the Sassacus. Steam filled the Union ship and killed several men, forcing the Sassacus out of action.

The Union side-wheelers Mattabesett and Wyalusing continued to engage the ram. The action continued for three hours until halted by darkness, but the ram was little damaged. The Albemarle then withdrew up the Roanoke River, and the Union side-wheelers Commodore Hull and Ceres took up position at the river’s mouth to try to prevent the ram from reentering the sound.

With the Albemarle posing a serious threat to Union coastal operations, Captain Smith sought to find a way to destroy it, but Union monitors drew too much water to operate in the sound, and wooden ships were too vulnerable. The destruction of the ram was finally accomplished by a spar torpedo launched on October 28, 1864.

CSS Albemarle

One of a number of powerful Confederate ironclad casemated rams and certainly one of the most famous Confederate warships. The Albemarle was the first of a two-ship class-the other being the Neuse-constructed by Gilbert Elliot at Edward’s Ferry on the Roanoke River in North Carolina. The smallest of Confederate naval constructor John L. Porter’s coastal defense ironclads, it was laid down in April 1863. The Albemarle was launched in July and commissioned in April 1864. It was some 376 tons, 139 feet between perpendiculars (158 feet overall length), with a beam of 35 feet, 3 inches, and hull depth of 8 feet, 2 inches. Driven by two screws from two steam engines capable of 400 horsepower (hp), the Albemarle could make in excess of four knots. It had a crew complement of 150 men. Armed with only two 6.4-inch rifled guns, its deck armor was 1-inch iron plate. The casemate sides were all angled 35 degrees and were protected by two layers of 2-inch plate.

Damaged at launch, the Albemarle was taken to Halifax, North Carolina, for repairs and completion. The ship was completed in time to participate in a Confederate Army assault led by Brigadier General Robert F. Hoke against the Union blockading base at Plymouth, North Carolina, on April 17, 1864. Early on the morning of April 19, captained by Commander James W. Cooke, the Albemarle attacked and sank one Union gunboat, the Southfeld, and drove off another. It now controlled the water approaches to Plymouth and could provide valuable assistance to Confederate Army moves ashore.

On the afternoon of May 5, accompanied by the gunboats Bombshell and Cotton Plant, the Albemarle engaged a squadron of seven Union gunboats off the mouth of the Roanoke River. The Bombshell was captured early in the action, and Cotton Plant withdrew up the Roanoke. The Albemarle continued the action alone, disabling the Union gunboat Sassacus. The Albemarle posed a great threat to Union coastal operations because its shallow draft enabled it to escape the larger, deepdraft Union monitors, and it easily outgunned smaller Union coastal craft. For months the Albemarle dominated the North Carolina sounds.

Early on the morning of October 28, 1864, U. S. Navy lieutenant William B. Cushing sank the Albemarle at its berth, employing a spar torpedo mounted on steam launch Picket Boat No. 1. The Albemarle was the only Confederate ship lost to a Union torpedo. Destruction of the Albemarle enabled Union forces to capture Plymouth and gain control of the entire Roanoke River area. It also released Union ships stationed there for other blockade duties. The Union Navy subsequently refloated the ironclad. Towed to Norfolk in April 1865, the hull was repaired, and the ship was taken into the U. S. Navy. It was condemned and sold on October 15, 1867.

October 28, 1864

The Confederate ironclad ram Albemarle posed a great threat to Union coastal operations in Albemarle Sound, and the Union Navy was determined to destroy it. With ironclads drawing too much water and wooden gunboats too vulnerable, a boat raid appeared to be the only option. On May 25, 1864, five volunteers went up the Roanoke River in a boat with two 100-pound torpedoes (mines), hoping to place them against the ram’s hull at night. The men were discovered before they could reach their objective, but all managed to escape.

In early July, North Atlantic Blockading Squadron commander Rear Admiral Samuel P. Lee met with 21-year-old Lieutenant William B. Cushing and asked him to lead another effort. Cushing proposed several plans, and Lee approved an attack by two launches fitted with spar torpedoes, but sent Cushing to Washington to secure final approval from the Navy Department. When Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles agreed, Cushing proceeded to New York City and there purchased two 30-foot steam launches and armed each with a 12-pounder Dahlgren howitzer. Each launch had at its bow a 14-foot-long spar that could mount a torpedo and be lowered by a windlass. Once the torpedo was in position under the target ship, a tug on the line would release the torpedo to float up under the hull. A second line would activate the firing mechanism. Cushing planned for the first launch to carry out the attack, while the second fired canister from its boat howitzer and stood ready to attack should the first attempt fail.

Both launches experienced engine problems on the trip south, and one had to be scuttled off Virginia, where its crew was captured. The other, Steam Picket Boat No. 1, arrived safely in the North Carolina sounds on October 24, whereupon Cushing revealed his plans to the crew. All seven volunteered.

Meanwhile, Rear Admiral David D. Porter had replaced Lee, and he approved Cushing’s request to undertake the mission with only one launch. Cushing set out on his attempt the night of October 26, 1864, but the launch grounded at the mouth of the Roanoke. The crew managed to free the launch, but the mishap forced Cushing to postpone his attempt until the next night.

The night of October 27 was dark and foul, and Cushing was able to get close to the Plymouth waterfront where the Albemarle was moored. Fourteen volunteers accompanied him. The launch towed a cutter with 2 officers and 10 men to neutralize the Southfield, which the Confederates had scuttled in the middle of the river about a mile from Portsmouth to serve as a picket.

The steam launch passed undetected within 30 yards of the Southfield, when at about 3:00 a. m. on October 28 a sentry ashore gave the alarm. Cushing immediately ordered the cutter to cast off, to make for the Southfield, and to secure it, while the launch got up steam for the run to the Albemarle.

The Confederates opened fire on the launch from both the Albemarle and the shore. Pickets ignited a ready bonfire to provide illumination, but this also enabled Cushing to spot a protective boom of logs around the ram. Calmly ordering the launch about, Cushing then ran it at full speed toward the obstruction while firing canister from the boat howitzer against the Confederates ashore.

Striking the boom at high speed, the launch rode up and over the logs and came to rest next to the Albemarle. As bullets whizzed around him, Cushing somehow managed to lower the spar under the ram and detonate it. When the torpedo went off, the resulting wash of water swamped the launch.

The explosion tore a gaping six-foot hole in the ram, causing it to settle rapidly. Of the 15 men in the launch, only Cushing and 1 other escaped; 2 drowned, and 11 were captured. All those on the cutter returned, bringing with them 4 prisoners from the Southfield.

Admiral Porter hailed the event, and the Union ships fired signal rockets in celebration. Destruction of the Albemarle enabled Union forces to retake Plymouth and control the entire Roanoke River area, and it released Union ships there for other blockade duties. Congress commended Cushing and advanced him to lieutenant commander.

References Elliott, Robert G. Ironclads on the Roanoke: Gilbert Elliott’s Albemarle. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane, 1999. Navy Historical Division, Navy Department. Civil War Naval Chronology, 1861-1865. Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1971. Still, William N., Jr. Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1985. Schneller, Robert J., Jr. Cushing: Civil War SEAL. Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2004.