The Peninsula Campaign and Trench Warfare

When General George McClellan persuaded Lincoln (against the latter’s judgement) to leave only 75 000 men guarding Washington from behind fortresses and land more than 100 000 men on the Yorktown Peninsula on 22nd March 1862 to strike at Richmond by sea, he sowed the seeds of failure by keeping secret from the President the fact that he was leaving only 50 000 to guard the capital. For when Lincoln discovered the deceit, he withheld 25 000 men from McClellan. By then the General was enmeshed in what amounted to almost constant and costly siege warfare against a series of well-entrenched lines of resistance, dug across his predicable line of advance through the ten-mile neck of the peninsula, but guarded by only 60 000 enemy troops under General Joseph Johnston.

The campaign developed a pattern hitherto unknown in warfare. Excepting sieges of fortified cities, combat in the past had been of short duration, major battles rarely lasting for more than a day. The Peninsula campaign, commencing with the Battle of Kernstown on 23rd March as part of General Jackson’s diversionary activities in the Shenandoah Valley, and ending in the withdrawal of Federal forces from the Peninsula in August, consisted of almost ceaseless fighting. Including the siege of Yorktown from 4th April to 4th May, there were no less than six major battles in the Valley and nine in the Peninsula, connected by continual skirmishing and one major raid by a cavalry division. Moreover, the Peninsula fighting coincided with a major campaign in the west, on either side of the Mississippi, where the struggle to control that jugular vein of the Confederacy culminated in the bloody Battle of Shiloh on the 6th and 7th April; the capture of New Orleans by a Federal fleet of 17 warships under Admiral David Farragut on 25th April; and the fall of Memphis to Federal river gunboats on 6th June. Losses were colossal – 14 000 Federal and 11 000 Confederate troops at Shiloh alone. Exhaustion became endemic, halting operations.

Although these heavy losses could partly be ascribed to errors of raw troops, as well as to poor staff work, the underlying reasons were improved technology which had redoubled firepower, and crippling deficiencies in communication which technology had not yet solved. When McClellan advanced from Yorktown in the direction of Richmond, his progress was slowed by an out-numbered Confederate rearguard which gave ground only grudgingly on a wide front. This was possible because no longer did men need to be packed into tight ranks in order to generate sufficient volume of fire to maintain their position against assault. Reciprocally, the thinning out of ranks made them less vulnerable to incoming fire. Such gams were ameliorated further when men took to lying down to shoot or, better still, made a point of firing from trenches or behind cover instead of standing up in the open, as so recently in the past decade. Not that either army was yet able to apply the full devastating potential of modern weapons. Many old, muzzle-loading rifles were still in service, but a sound of the future ripped forth at the Battle of Fair Oaks when on 31st May, within sight of Richmond, a battery of hand-operated Williams machine-guns chimed in to support the first Confederate counter¬ stroke – a battle which was to save their capital city though it failed, with losses of over 6000 men, to drive McClellan back.

As had been shown in the Crimea and at Solferino, head-on assaults against a well emplaced enemy of equal calibre were no longer profitable operations of war. Even less viable was cavalry against modern artillery and rifle fire. The only chance of making a worthwhile mounted contribution was to ride through gaps in the enemy lines, both for reconnaissance and for raids, into the wide-open spaces of the enemy rear. In a country the size of America, and with relatively small forces engaged, there would always be gaps and nobody was better at exploiting these than General JEB Stuart, as he demonstrated between 12th and 15th June when he rode right round McClellan’s army, creating havoc in the rear and returning to Lee (given command in the field after Fair Oaks) with invaluable information about Federal dispositions.

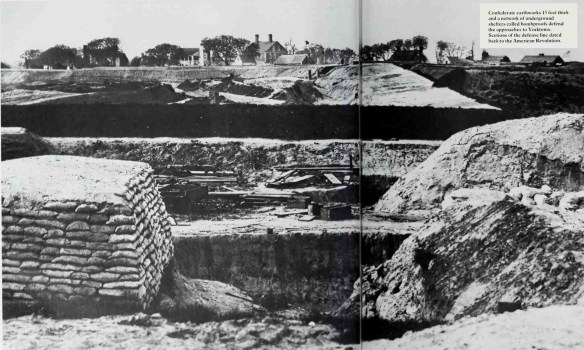

Trench Warfare – The Lines of Petersburg

When Grant deluded Lee as to his true intentions after the Wilderness Campaign, managing suddenly to appear in mid-June with massed forces at Petersburg instead of further north as expected, the thinly defended city lay at his mercy. But war weariness and a conditioned caution held back the Federal troops who now approached all entrenchments warily as a matter of course. One quick determined rush by a Corps on 15th June 1864 might well have broken through. Three days later an army of 65 000 was insufficient to overcome the 40 000 men Lee had rushed to the spot by rail. Faced at first by an improvised line, the initial Federal assault failed from lack of co-ordination. Detachments advanced independently, inadequately supported by artillery, and were pinned to the ground by fire of only moderate intensity. By the time a set-piece attack could be launched on the 18th, the volume of defensive fire was annihilating, compelling Grant to call a halt and commence probing the city’s southern flank with a view to isolating it. Keeping pace with each Federal sidestep to their left, the Confederates extended their entrenchment to their right, always in time to meet each assault while fiercely contesting Grant’s further attempts to cut the line to Richmond or the one running westward from Petersburg. Assault was usually of the battering-ram sort – a blasting of the selected point of attack by artillery and mortars (the latter, with their plunging fire, being particularly suitable for striking at the deeper enemy emplacements) followed by a massed infantry charge.

Historians accuse those in charge of a succession of failed set-piece attacks with bungling. To some extent they are right, although they tend to overlook that the dimensions and ferocity of modern war had produced a complex problem beyond the knowledge and technology of the day to solve. `In war’, said a Prussian officer called Hindenburg, many years later, `only simple plans work’. In 1864 simplicity could not be adopted. Even if every plan had been perfectly devised, staff work impeccable, communication arrangements fault¬ less and every order executed implicitly, the weather, or the enemy could be expected to disrupt them. But nothing could be perfect in this form of warfare, with masses of men and numerous weapon systems somehow to be coordinated. Humanity failed in all its unpredictability. That way chaos and slaughter were assured.

The attack on the Redoubt at Petersburg on 30th July demonstrated in utter confusion the inability of commanders to make human courage prevail over material factors and human frailty. As a powerful augmentation of the, by now, conventional artillery concentration of fire, a mine containing four tons of black powder was to be exploded beneath the redoubt and its defenders. Placed in a cross shaft at the end of a 511-foot tunnel which a regiment of coal miners secretly dug, it was blown at dawn without warning to the enemy. General Ambrose Burnside, whose four divisions of infantry were to exploit the explosion, seems to have relied too much upon the shock effect of the mine; beyond doubt the measures he took to ensure that the troops not only occupied the crater but pressed on rapidly beyond, were ambiguous and unambitious. As for the troops, so staggered were they by the enormity of the explosion, the air pressure of its blast and the scene of carnage which met their eyes when they poured into the crater, that they lost all sense of purpose and stayed there all morning, poking about among the grisly ruins of dismembered men and equipment. On the Federal side leadership came to naught while among the Confederates initial shock was gradually overcome and a counter-stroke launched in the afternoon. Artillery sealed off the flanks of the 500-yard breach in the defences, as infantry rushed to the lip of the crater where they fired volleys into the disorganized mob below. The Federals were flung back with the loss of 3793 men. That day the Confederates lost 1182, including those blown up.

For the rest of the summer and into the fall, Grant strove fitfully to break the deadlock in front of Richmond and Petersburg, creating for the logistic support of his troops a comprehensive conglomeration of base depots, camps and railway spurs leading to within artillery range of the enemy. Facing the Confederate capital the entrenched front was some 37 miles long, manned by 90 000 well-provisioned Federal troops on one side, and 60 000 deprived but fanatically determined Confederates on the other. Try as he would to smash through, Grant was defeated. Likewise, Lee was rebuffed when in March 1865, a last sortie took Fort Stedman but got no further than its ramparts before it was stopped by a Federal counterattack. In a four-hour battle, the attackers lost twice as many men as the defenders – 4000 to 2000.

Had Grant’s exploits comprised the sole Federal effort in 1864 they could well have led to his and President Lincoln’s downfall in an election year. The disgruntled General McClellan was campaigning for the Democratic candidacy with a call for an end to the war. He might have won if General William Sherman, taking advantage of the dram of Confederate strength to the east, had not struck the decisive blow in the west.