Despite the lack of a Muslim capitulation following the Battle of the Bridge, there was a definite lull in the fighting along the Euphrates, stretching out to perhaps a year. With so many of his forces deployed in Syria against the Romans, Umar seems to have had some trouble in finding volunteers for a proposed reinforcement of the Muslim outposts along the Euphrates. So low were volunteer numbers that the caliph turned to a thus far untapped section of Arabia – those tribes that had rebelled during the Ridda Wars. Abu Bakr had refused to use these tribes due to their apostasy but Umar, combining outward leniency with military pragmatism, was only too happy to allow them to enlist. However, even with these new resources, Umar was still unable to bring together a force of any substantial size. Several different tribes did contribute contingents but it was the Tamin and the Bajila who provided the most, around 1,000 men each. Such was Umar’s need for men that the Bajila leader, Jarir b. Abdullah, had a strong enough bargaining position to see himself not just appointed commander of this new force but also permitted the quarter share of the spoils that would normally be due to the caliph. This lofty position accorded to Jarir, along with the size of the force under his command, seems to have led to confrontation with al-Muthanna, who retained some semblance of overall authority.

Despite his wound, al-Muthanna wasted little time in reinitiating the type of raiding that had been so profitable in the run-up to the Battle of the Bridge. Some accounts suggest that he also won a pitched battle against the Persian army at Buwayb. However, it would appear that this `Battle of Buwayb’ was the exaggeration of a minor engagement `designed to enhance the reputation of al-Muthanna and his tribe among later generations and to counter the disgrace of his humiliating defeat at the Battle of the Bridge.’ Even when the reinforcements of Jarir arrived at Hira, the casualties suffered in the reverse at the Bridge and the fear of a repeat performance saw to it that Muslims were careful to avoid any large-scale confrontation with the Persian army, sticking to hitand-run raids.

This somewhat precarious position of not being able or lacking the confidence to fight a pitched battle, along with the squabble over superiority between Jarir and al-Muthanna, led Umar to launch an even more comprehensive recruitment drive. To diffuse the tension between Jarir and al-Muthanna, these new recruits were to be led by a man who was clearly superior to both. Umar originally meant for that person to be himself, with some preparations being made for his journey to Hira. However, he was talked out of this gambit, agreeing instead to appoint a companion of Muhammad to the overall command of the Iraqi front. The choice fell upon Sa’d b. Abi Waqqas, a veteran of the Battle of Badr, who arrived at Medina at the head of 1,000 Hawazin. Sending out calls for further recruits as he travelled north along the MedinaHira road, by the time Sa’d arrived along the Euphrates he must have commanded an army comparable to any Muslim force that had yet been sent against the Sassanids. The Jarir/al-Muthanna squabble had been settled with the latter’s succumbing to his wound and Sa’d also quickly diffused any potential trouble from the Shayban by marrying al-Muthanna’s widow and appointing al-Muthanna’s brother, al-Mu’anna, to council.

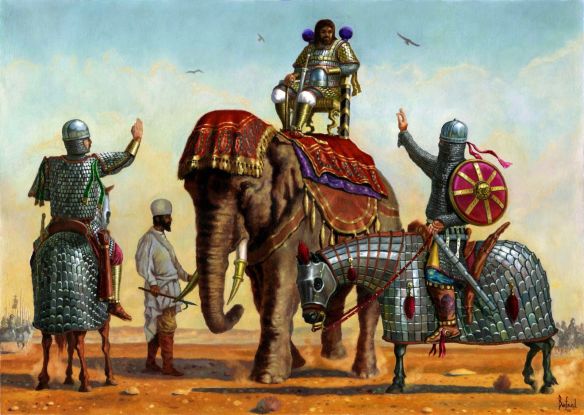

The arrival of Sa’d proved to be well timed, for, having finally established full control over his realm and buoyed by Bahman’s victory at the Battle of the Bridge, Yazdgerd was now giving his full attention to his southern border. For the task of crushing this Muslim menace, the Persian king appointed Rustam Farrokhzad to command the large force of infantry, cavalry and elephants that he was bringing together. However, there is little agreement over just how big this Persian force was, with anything from 30,000 to 210,000 being recorded. However, despite the absurdity of the latter, it is likely that even the smallest recorded size of Rustam’s force held a significant manpower advantage over the combined forces of Sa’d.

Despite some sources claiming that the Muslims were able to field a force of enormous proportions, it is far more likely that Sa’d commanded a force of between 6,000 and 12,000.20 Attempts have been made to back this up by establishing the tribal composition of the Muslim force, with six distinct contingents being identified: Sa’d’s 1,000 Hamazin; 2,300 Yemeni; 700 from al-Sarat; anything from 2,800 to 7,000 tribal recruits from central Arabia; the pre-existing forces of Jarir and al-Muthanna, which probably numbered around 3,000; further reinforcements sent by Umar of up to 2,000; a contingent of 400-1,500 under al-Mughira b. Shu’ba from south-eastern Iraq; and two separate armies sent from Syria under Sa’d’s relative, Hashim b. Utba, and Iyad b. Ghanm of 300-2,000 and 1,000-5,000 respectively. Sa’d is also accredited by some of the sources with bringing a greater level of organisation to this army, dividing his men into units, each with their own commander and based on a subdivision of ten men. While it is likely that there is some anachronistic reporting from the sources, it is possible that lessons were learned from the defeat of Abu Ubayd on the Bridge and that Sa’d’s army was far more organised as a military force than the previous Arab hordes of tribal warriors.

Marching from Ctesiphon, Rustam took up a position opposite the Muslim force about thirty miles to the east of Hira. Neither Rustam nor Sa’d seems to have been overly hurried in forcing battle on their opponent, as it is suggested that, while both forces took up their respective positions in July 636, the Battle of Qadisiyyah does not seem to have occurred until mid-November. It would be easy to suggest that Sa’d’s failure to force a confrontation was due to a wariness of another sizeable defeat; however, he did not attempt to extricate his men from battle at any stage. His sending out of reconnaissance scouts and raiding parties into Mesopotamia, along with his arrogant demand that Rustam accept Islam, also suggest that he was not shirking away from a fight. However, it does seem that he was in repeated contact with Umar and will therefore have known that there was a steady drip of reinforcements from Arabia, Syria and southern Iraq on the way to bolster his ranks. For his part, Rustam may have been hoping for a repeat of the Muslim debacle at the Battle of the Bridge. However, Sa’d did not allow himself to be goaded into the same kind of reckless attack that had cost Abu Ubayd so dearly. It is also possible that Rustam, much like Heraclius and his generals in Syria, may have thought that the Muslims might crumble in the face of the large host he had brought to Qadisiyyah.

Battle of Qadisiyyah, 636: Deployments.

Day 1 – 16 November 636

The course of the Battle of Qadisiyyah is muddled by the lack of `an overall picture of the evolving tactical situations’ and relies heavily on oral traditions, which tend to embellish the actions of individuals and tribes. However, it appears that by mid-November Rustam had decided that, as the Muslims gave little inkling of retreating and had actually increased in strength through reinforcements, he would have to initiate battle. With that, early on 16 November 636 he ordered a canal of the Ateeq that separated the armies to be filled in to allow his forces easy passage. With the Persians safely across the canal, both forces now deployed for battle in a similar formation of four separate divisions of infantry, each supported by a division of cavalry. Aside from size, the only real difference in the tactical layout of the armies was that the Sassanids had a corps of eight elephants deployed in front of each of their four infantry divisions.

The Persian right was commanded by Hormuzan, the right centre by Jalinus, the left centre by Beerzan and the left by Mihran. Rustam took up a position behind his right centre near the Ateeq to provide him with a good view of the battlefield. The Muslim right was commanded by Abdullah b. al-Mutim, the right centre by Zuhra b. al-Hawiyya, the left centre by Asim b. Amr and the left wing by Shurahbeel b. al-Samt. The cavalry contingents of the right centre and right wing were commanded by Ath’ath b. Qais and Jarir respectively. Sa’d seems to have been taken unwell in the run-up to the battle and was therefore not active on the battlefield, choosing instead to take up a position in the town of Qadisiyyah from where he could direct operations through his deputy, Khalid b. Arfatah.

Battle of Qadisiyyah, 636: Day 1, Phase 1

With the two armies arrayed less than a kilometre apart, the increasingly traditional duels took place, with the Muslim mubarizun once again proving their superiority. By the middle of the day, having lost several of his champions and not wanting to risk more of them or the morale of his men, Rustam ordered Mihran to launch an attack against the Muslim right. Preceded by a hail of arrows, the Persian elephants charged Abdullah’s infantry forcing them backwards. An attempt by Jarir to stabilise the situation by leading a flank attack with his right-wing cavalry was intercepted and routed by Mihran’s heavy horse. Recognising that his right flank was in danger, Sa’d reacted quickly to restore it. From the Muslim right centre, regiments of Ath’ath’s cavalry and Zuhra’s infantry launched a flank attack on Mihran’s infantry while Jarir’s cavalry reformed and checked the Sassanid cavalry advance. These counter-attacks undid Mihran’s early advances and restored the Muslim line.

Battle of Qadisiyyah, 636: Day 1, Phase 2

With his left-wing attack stalling, Rustam ordered similar attacks on the Muslim left and left centre. Once again, in the face of a barrage of arrows, flank attacks by Hormuzan and Jalinus’ cavalry, and the trampling power of the elephants, the Muslims began to give ground. However, Asim was able to blunt the Persian charge. His light infantry and archers disrupted the elephants to such good effect that Jalinus had to remove them from battle. Building on this success, Asim launched a counter-attack with his entire right centre that forced Jalinus’ corps back to its starting point. Buoyed by this, Shurahbeel’s left was able to affect a similarly successful counter-attack, first taking out the elephants and then forcing Hormuzan back. With three-quarters of the Sassanid force now in some kind of retreat, Sa’d attempted to take advantage of this by ordering a general attack along his entire line. It is suggested that this Muslim offensive was only rebuffed by the failing light and Rustam rallying his men by personally joining the fighting. While Sa’d may have ended the day on the offensive, despite the casualties endured by both sides, the fighting had been largely inconclusive.

Day 2 – 17 November 636

The second day of the battle began in a similar vein to the first with Sa’d sending forward his mubarizun to challenge Persian champions. This second set of duels may seem like something of a missed opportunity by Sa’d, given the momentum that his men had gained through their counter-attacks in the latter part of the first day. However, it is possible that not only was he looking to further undermine Persian morale, Sa’d may also have known of the imminent approach of reinforcements from Syria, which began to arrive while the duels were still taking place. These reinforcements under Hashim b. Utba were divided into several groups in order to give the Sassanids the impression of a steady stream of men arriving in the enemy camp. With the continued success of the mubarizun and the arrival of Hashim, Sa’d decided to launch a similar general attack along the length of the battle line. However, perhaps again with Rustam risking his own life in the fighting, the Sassanid lines remained firm throughout the day and at dusk both armies retreated back to their camps.

The arrival of this first batch of Muslims reinforcements from Syria brought with it an individual who would achieve particular prominence throughout the remainder of the Battle of Qadisiyyah and the Muslim advances in the years to come – the commander of Hashim’s advanced guard, Qaqa b. Amr. Even before he arrived on the battlefield, Qaqa was receiving praise for being at least partially responsible for dividing his advanced guard into numerous groups to give the impression of larger numbers. Once he reached Qadisiyyah, Qaqa is credited with plunging straight into the ongoing duels and personally killed not only Beerzan, commander of the Persian left centre, but also Bahman, the victor at the Battle of the Bridge. During the subsequent general attack ordered by Sa’d, Qaqa is recorded as deploying a ruse to disrupt the dangerous Sassanid cavalry, disguising camels as monsters. He is also said to have led a group of the mubarizun through the Persian lines in an unsuccessful attempt to kill Rustam. Such inventiveness and initiative would appear to have impressed Sa’d as it is reported that Qaqa was promoted to battlefield command for the remainder of the fighting. However, without taking too much away from his potential ingenuity and skill, many of these episodes attributed to Qaqa seem suspect and were probably the invention of later Muslim written and oral sources.

Battle of Qadisiyyah, 636: Day 3, Phase 1

Battle of Qadisiyyah, 636: Day 3, Phase 2.

Day 3 – 18 November 636

The threat of further reinforcement of the Muslim army encouraged Rustam to seek a decisive breakthrough on the third day of battle. Therefore, the Persian commander launched a full-scale general attack. Its ferocity, particularly the elephants, pushed the Muslim corps back and opened sizeable gaps between them. Rustam took advantage of this by sending his cavalry into these breaches. One Sassanid cavalry regiment is thought to have penetrated as far as the old palace at Qadisiyyah that Sa’d was resident in. With his line in trouble, Sa’d had to react quickly and his immediate aim was to neutralise the Persian elephants wreaking havoc amongst the Muslim infantry. To that end, he ordered his skirmishers, archers and spearmen to concentrate on the great beasts and by the middle of the day the Muslims had succeeded in driving them back into the Sassanid ranks. Taking advantage of the confusion the retreating elephants caused, Sa’d then ordered an all out counter-attack by his forces. However, despite the confusion caused by the retreat of the elephants and a repeat of Qaqa’s disguised camels, the Sassanid forces once again stood firm. With that, the battle settled into one of attrition as both sides inflicted heavy casualties on their opponent without being able to break the other, even as night fell.

Battle of Qadisiyyah, 636: Day 4, Persian Collapse.

Day 4 – 19 November 636

As the fighting of the third day continued into the early hours, breaking only at the first signs of daybreak, it might be expected that there was little or no fighting on the fourth day. Rustam and his army certainly seemed to think so. However, Sa’d and his increasingly prominent battlefield commander, Qaqa, saw this as an opportunity to force a decisive breakthrough. Addressing his troops, Qaqa proclaimed that, as the Persians were tired from the previous day and night’s fighting, an unexpected attack so quickly after the break-off of hostilities would give the Muslim army victory. With that, Asim’s left centre attacked Jalinus’ right centre, followed by a general advance by the rest of the Muslim line. This took the Sassanids by surprise and, with the Muslim cavalry staging flanks attacks, the corps of Jalinus and Hormuzan were soon giving ground to those of Asim and Shurahbeel. Hormuzan stabilised the Persian right flank and, as Zuhra and Abdullah had been unable to match the progress of Asim, Hormuzan’s successful counter-attack left both flanks of Asim’s corps exposed, forcing it to also retreat.

However, it was at this point that news of the decisive move of the battle began to filter through to the Persian ranks. Taking advantage of Asim’s early success against Jalinus, Qaqa had led his band of mubarizun through the Persian right centre and killed Rustam. As news of the death of their commander spread amongst the Persian ranks, resolve began to dissolve as the weight of three days’ hard fighting with little sleep the previous night began to weigh heavily. Recognising his opportunity, Sa’d ordered one last general attack from his own exhausted forces in the hope of taking advantage of the demoralising effect of Rustam’s death. Under this renewed Muslim onslaught, the Persian line finally buckled and then broke.

With the death of Rustam, Jalinus took charge of the Persian force and, while he could do nothing to prevent their defeat, he does seem to have held the remaining Persian units together in an orderly retreat across the Ateeq and then the Euphrates back towards Ctesiphon. However, much like their compatriots in the aftermath of Yarmuk, Sa’d exploited his victory to its fullest. While Jalinus was able to establish defensive bridgeheads over the Ateeq and Euphrates, allowing a large proportion of his surviving forces to cross safely, once the Persian army was exposed on the alluvial plains of Mesopotamia they were ruthlessly pursued and cut down by Sa’d’s cavalry. Much like Vahan’s army, the force that Rustam led out from Ctesiphon ceased to exist.

There is some suggestion that Heraclius and Yazdgerd planned to coordinate their offensives of 635. They may even have cemented this understanding with a marriage alliance between the two. However, if such a marriage took place or was ever planned, the name of the female offered to Yazdgerd by Heraclius or her relationship to the emperor was not firmly established. Furthermore, whatever coordination the emperor and king hoped to accomplish aside from two individual victories is difficult to ascertain. Aside from Khalid’s trek to Damascus in early 634, the possibility of Roman troops being at the Battle of Firaz and the arrival of Hashim at Qadisiyyah, the theatres in Roman Syria and Persian Mesopotamia were completely independent from each other. If such a dual venture did take place, it must have called for simultaneous action and decisive military victories. As it was, neither was achieved. The Roman and Persian counter-offensives were launched months apart and neither Vahan nor Rustam were able to defeat their Muslim opponents.

But, of course, the most important point about such proposed coordination was that not only did both Vahan and Rustam fail to achieve decisive victories, they both suffered catastrophic defeats that led to the complete undermining of the defensive positions of both Syria and Mesopotamia. By the end of the following year, the Romans would be forced back beyond the Taurus Mountains, attempting to establish some sort of defensive line capable of preserving their Anatolian provinces, while Qadisiyyah initiated a series of further defeats and retreats that would not only see the Persians lose Mesopotamia but over the course of the next twenty years lead to the virtual extinguishing of the Sassanid state.