14 OCTOBER 1943

“The mission of October 14th had demonstrated that the cost of such deep penetrations by daylight without fighter escort was too high … the Eighth Air Force was in no position to make further penetrations either to Schweinfurt or to any other objectives deep in German territory.” US Official Report on the Schweinfurt Raid.

It is a great tragedy of war that commanders can blindly persist with plans which have been repeatedly proven to be dangerously misguided. After World War I, visionary young officers in a number of countries argued that in the future wars would be won not by armies or navies but by fleets of aircraft bombing enemy cities, in what became known as `strategic’ bombing. World War II saw the creation of such strategic bombing fleets, chiefly by the British and Americans, of which perhaps the strongest and the most famous was `The Mighty Eighth’, the USAAF (US Army Air Force) Eighth Air Force. This was air war in what had always been seen by its advocates as its most pure and effective form. But the practical problems of carrying out long-range strategic bombing were immense. One issue in particular came to dominate the argument: in the absence of an effective fighter escort with enough range, was it possible for heavy bombers to fly unescorted over the heart of Germany in daylight? After heavy losses sustained in the first attacks on German cities after May 1940, the Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command concluded that it was not, and switched to night bombing. The USAAF persisted in unescorted daylight bombing. On 14 October 1943 it launched an air armada against Schweinfurt, one of the most heavily defended industrial towns of the Third Reich.

The Strategic Context

On 21 January 1943 the Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) issued the `Casablanca Directive’ in support of a plan from Lieutenant General Ira C Eaker, commander of Eighth Air Force, to start a Combined Bombing Offensive (CBO) against Germany, with the British bombing at night and the Americans by day. This confirmed that the primary objective of the CBO was `the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military industrial and economic system, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened’.

Planned in four phases between April 1943 and April 1944, the CBO only reached its full significance when the `Point Blank Directive’, which amended the `Casablanca Directive’, was issued by the CCS on 10 June 1943. While listing various categories of targets, it gave absolute priority to the destruction of German fighters and the factories where they were built, as it was realized that `Operation Overlord’, the projected liberation of France in 1944, could not be launched until air supremacy had been achieved. The directive reflected also the express wish of the US bomber commanders, who, during the first 14 operations of the CBO, had sustained virtually all their losses from enemy fighters as opposed to Flak (German anti-aircraft fire). Eaker concluded that only once he had annihilated the German fighter air arm would it be safe to penetrate into the heart of Germany.

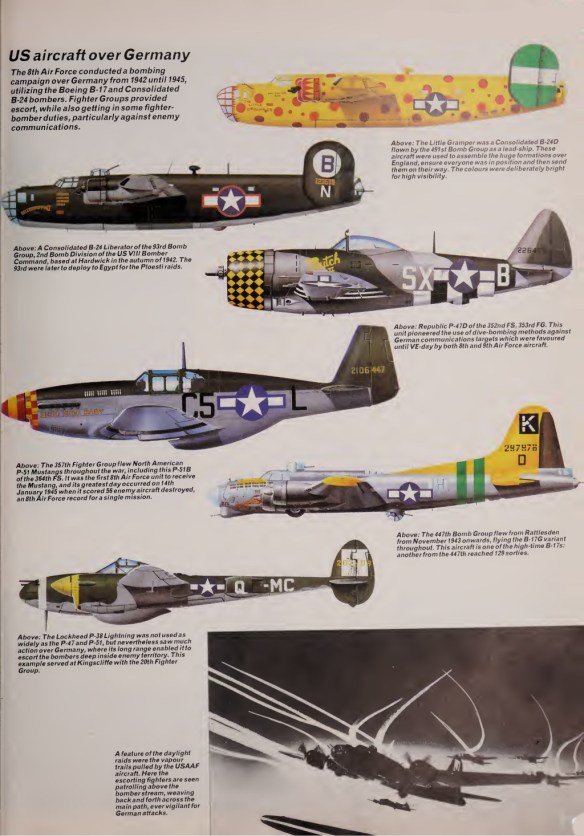

Behind this rationalization of objectives lay the prolonged, often bitter Anglo-US debate over the merits of daylight strategic bombing. While General Henry H (`Hap’) Arnold, commander of the USAAF, had been greatly impressed by the British theory of strategic bombing, neither he nor his subordinates approved of the costly results of RAF night bombing. Daylight bombing, the Americans argued, would enable them to hit pinpoint targets, such as oil installations and aircraft factories. The main US heavy bombers, the B-17 `Flying Fortress’ and B-24 `Liberator’, were also less suited to night flying.

The American Plan

A draft version of `Point Blank’ issued on 14 May had already noted the critical importance of ball bearings to the German war effort. The `concentration of that industry’, it pointed out, made 76% of German ball¬ bearing production `outstandingly vulnerable to air attacks’. US strategic planners prioritized the five ball-bearing plants located at Schweinfurt – which between them supplied 52.2% of all German ball-bearing production, and 39.1% of ball bearings obtained from all sources – for their increasingly ambitious daylight bombing offensives. RAF Bomber Command declined to take part in an offensive against such small, remote targets.

The first major USAAF raid on Schweinfurt, and subsequent raids on Germany, had already demonstrated the immense problems in planning and executing such deep penetration operations, especially when the limit of US fighter cover was 250 miles out from England, barely reaching the westernmost towns of Germany. A double mission of 376 Flying Fortresses had been despatched to Schweinfurt and Regensburg on 17 August, unescorted for most of the way. In the consequent ferocious air battles, 60 US bombers were shot down, mostly by the Luftwaffe fighter command, a loss rate of 16%. Since each crew flew 25 missions before a rest, a loss rate above 4% for each mission made death almost a statistical certainty.

Despite these losses and the evident problem of lacking long-range fighter aircraft protection, US commanders stubbornly persevered with plans for a second raid on Schweinfurt. Lieutenant General Eaker remained convinced of the strategic and economic necessity of completely eliminating ball-bearing production at these key plants, which had only been partially destroyed during the first raid. Eaker also remained confident of the merits of precision bombing, so recently improved by the invention of the Norden bombsight, and new electronic and radar navigation systems. Despite the recent heavy losses, US commanders remained convinced of the high survivability of their self-defending bomber force, provided they strictly adopted the correct tactical formation. By 1943 US bombardment groups had developed the `combat box’, a new staggered formation comprising three squadron formations, each covering the other at different heights and with complementary arcs of fire. Within this box, it was theorized, the recently increased armament of the B-17s and B-24s (up to twelve .50-calibre machine guns, mostly situated within power-driven plexiglass turrets), could successfully protect them from all angles. Given such an extremely tight formation, it was contended that the R-17s and the B-24s, carrying 5,000-lb and 8,000-lb bomb loads respectively, could fend off any serious German attacks.

The second Schweinfurt raid was scheduled by Eaker and his staff for Thursday, 14 October 1943. Three simultaneous penetrations were initially planned. Eighth Air Force’s 1st and 3rd Bombardment Divisions, comprising 360 B-17s, were to cross the Netherlands in two task forces 30 miles apart. Meanwhile 60 B-24s of 2nd Bombardment Division would form a third task force to fly further south. As the B-17s’ routes would take them beyond normal maximum endurance, it was planned that those without long-range `Tokio’ fuel tanks would carry an extra fuel tank in the bomb bay, reducing their bomb-load capacity. One group of short-range P-47 Thunderbolt fighters was to escort each of the penetrating task forces as far as possible, and an additional group was to provide cover from about half-way across the English Channel. To protect stragglers, two squadrons of RAF Spitfire IXs would sweep the assembly area five minutes after the last of the attacking forces had left, and other RAF squadrons would be held in readiness for action if required.

The German Plan

The US plans had been conducted against the background of several ominous developments in German ground and fighter defensive organization. During 1943 the emphasis had shifted increasingly to concerted action against daylight raiders. Even though the British raids over Germany were still more numerous, the US precision raids were of much greater potential consequence for the German war industry. The first raid on Schweinfurt had come as a particular shock to the German high command, who regarded the ball-bearing industry as their Achilles’ heel. After this first raid, Albert Speer, the armaments minister, had predicted that if the raids continued at such levels the German armaments industry would come to a standstill in four months.

The major reorganization required to meet these new mass precision raids was no easy task. There was an overall shortage of trained and experienced Luftwaffe pilots, with many of them increasingly diverted to the beleaguered Eastern Front. During 1943, as the tide of war slowly turned against Germany, Luftwaffe fighter defences were further undermined by direct political interference by Adolf Hitler himself, who ordered a reduction in fighter construction in favour of ground-level attack aircraft and bombers. Consequently, of the 7,477 single-engined fighters produced in the first eight months of 1943, only a small proportion were allocated to home defence units

Despite these crises, by August 1943 German defensive plans had created a formidable network. This consisted basically of two elements – anti-aircraft guns and fighters. In the course of 1943 the number of Flak guns deployed in Germany significantly rose from 14,949 to 20,625, chiefly light guns of 20-40 mm calibre and heavier guns of 88-128 mm calibre. New `Flak towers’ and associated guns were reorganized to provide arcs of predicted fire, to engage bombers from the start of their level bombing run with box barrages put up at their approximate height just short of their anticipated bomb release point.

Of far greater significance in German defence planning against future US daylight raids were its interceptor fighters, of which the most common were the Messerschmidt Me 109G, with a speed in excess of 380 mph, and the even faster Foche-Wulf FW 190A, compared to 200 mph for the US bombers. The basic Luftwaffe operational unit for defensive purposes continued to be the Jagdgeschwader (`fighter group’ or JG) of about 120 aircraft.

German methods and plans for attacking the improved US bomber formations increased in variety and efficiency during 1943. The main objective was for fighters to continually break up the bomber formations so that individual aircraft could be finished off as they fell away damaged. German fighter pilots soon realized that the new US box formations produced far less fire from the front than from any other angle. Consequently, the Luftwaffe developed several different methods of head-on attack, which varied from Scbwarm (`swarm’ of 4 aircraft) to Staffel (`squadron’ of about 12 aircraft) strength. Often flying parallel and in front of US bombers, on a signal from their coordinator (frequently in a converted Junkers Ju 88 light bomber) the fighters would sweep into their attack, either half rolling away in front of the bombers or pulling up over the top of them, and then flying back to attack from the front. By early August 1943, the increased firepower of the FW 190s also encouraged Schwarm-strength attacks in line abreast from the rear. During deep penetration missions such as Schweinfurt, fighters would refuel and each attack the bombers two or three more times.

Other methods of breaking up offensive bomber formations included using twin-engined aircraft, such as the Messerschmidt Me 110 and Me 410s, to fly above the tightly packed bombers and drop fragmentation bombs. Explosive rocket projectiles, carried by FW 190s and Me 109s, could also cause immense damage when lobbed into tightly packed bomber formations at between 1,000 and 1,700 yard range.

The Early Stages

From the very start, the massive bombing raid launched against Schweinfurt on 14 October 1943 was significantly compromised by the one uncontrollable factor in any battle plan: inclement weather. The heavily overcast conditions caused chaos at designated rendezvous points. This problem, combined with % the heavy losses of the previous week over Munster and elsewhere, meant that it was impossible to muster the projected 360 battle-worthy B-17s. The B-24s of 2nd Bombardment Division were also particularly badly affected. With only two units of 29 planes finally joining together, numbers were insufficient for any deep penetration raid, and they were forced to fly an uneventful diversionary feint across the North Sea towards the Frisian Islands.

Vivid memories of the first costly August raid meant that morale among many bomber crews was unusually low. A medical officer present at the final briefing noted how the first mention of Schweinfurt, `shocked the crews completely… it was obvious many doubted that they would return’. Over Walcheren Island, the escorting P-47 fighters managed to repel the first German attacks, made by single-engined fighters from JG26. It was a deceptively easy start. As on the first Schweinfurt raid, the Luftwaffe made its appearance in force at around 1.00 p. m., immediately after the P-47 escorts had turned back near Aachen.

The Main Battle

Between Aachen and Frankfurt the now unprotected 1st Bombardment Division faced a relentless onslaught, mainly from FW 190s and Me 109s. For three solid hours the unescorted bombers were exposed to the full fury of the German flak and fighters. Wave after wave of fighters closed in for the kill. Most of the tactics used by the German fighters that horrendous day had been used before – formation attacks, the use of rockets and heavy-calibre cannon, air-to-air bombing, concentration on one group at a time and on stragglers. But never before had the enemy made such full and expertly coordinated use of these tactics. As Lieutenant General Eaker later privately confessed to his superior General Arnold, the Luftwaffe `turned in a performance unprecedented in its magnitude, in the cleverness with which it was planned, and in the severity with which it was executed’. Most alarming for the US aircrews was the sheer scale of the enemy attacks. General Adolf Galland recalled that he `managed to send up almost all the fighters and destroyers [Me 110s and Me 410s] available for the defence of the Reich, and, in addition to this, some fighters of the Third Air Fleet (Luftflotte 3) in France. Altogether some 300 day fighters and 40 destroyers took part in the battle which for us was the most successful of the year’.

One unpleasant variation of the Luftwaffe’s normal tactics was the use of single-engined fighters as a screen for twin-engined aircraft to close in for rocket attacks. These rockets, which travelled slowly enough to be clearly visible, presented an especially chilling sight. One US bomber pilot recalled watching in horror as one rocket arched through his formation heading straight for a nearby B-17. Striking the fuselage just to the rear of the cockpit it tore open the side of the plane and blew one wing completely off. The pilot briefly glimpsed the men in the cockpit still sitting at their controls, then they were engulfed in flames.

The German fighters systematically concentrated on one formation at a time, breaking it up with rocket attacks and then finishing off cripples with gunfire. In a further comment upon this desperate period after the P-47s had turned back, another pilot remembered how `all hell was let loose… the scene [was] similar to a parachute invasion, there were so many crews bailing out’. It was a sadly mauled 1st Bombardment Division that finally reached the target from Frankfurt. Its leading element, 40th Combat Bombardment Wing, lost 27 aircraft before Schweinfurt was even reached – its 350th Group losing all but three out of 15 aircraft.

By contrast, 3rd Bombardment Division escaped far more lightly. Departing the English coast about 10 miles south of Harwich at 12.25 p. m., five minutes after the 1st Bombardment Division, it picked up its escort of 53 P-47s 30 minutes later after crossing the Belgian coast. At Eupen, just after the escorting P-47s had turned back, a sharp southward turn took the B-17s away from the route of 1st Division towards Trier and Mosel. Flying to the east of Luxembourg, the bombers avoided the Ruhr Flak concentrations. At 2.05 p. m., 3rd Division again turned east towards the `Initial Point’ of the bombing run, near Darmstadt. Only between Mosel and Darmstadt did the air battle intensify, and the first serious pass was made around the Trier area. By the time they reached Schweinfurt their leading formation, 96th Combat Bombardment Group, had lost only one aircraft.

The Bombing Run

The US bombing over the target itself was unusually effective. A sudden change of course near the `Initial Point’ confused enemy fighters, and the air attacks diminished significantly as the B-17s turned into their bomb run. For once the weather was kind, and good visibility allowed 1st Division to drop a high concentration of bombs on all its Schweinfurt target areas. Even the crippled 40th Group put over half its bombs within 1,000 feet of the aiming point. The thick smoke from 1st Division’s attack meant that 3rd Division was less successful. In all, 228 surviving B-17s dropped some 395 tons of high explosive bombs and 88 tons of incendiary bombs on and about all three of the big ball-bearing plants. Of 1,222 high explosive bombs dropped, 143 fell within the factory area, 88 of which were direct hits on the factory buildings.

After the final bombing run, 1st Division turned south and then west below Schweinfurt, but there was no let-up in the Luftwaffe attacks. Fighters from JG3 and JG51 attacked the trailing 41st Wing, while FW 190s shot down three B-17s of the leading 379th Group. Around Metz and Stuttgart, twin-engined night fighters joined the attack, continuing as the bombers flew across France. By the time of its return to England, 1st Division had lost a further 10 aircraft, making a total of 45 for the mission, not counting crew losses in damaged aircraft.

Having reached the target with relatively few losses, 3rd Division suffered much more heavily on the homeward journey. Immediately after leaving Schweinfurt a very intense attack took place by about 160 single-engined aircraft, backed by twin-engined Me 110s, Me 210s, and Ju-88s, with the lower flying bomber groups as the main focus. Particularly badly hit again was 96th Group; 14 aircraft were lost in the return.

Poor weather again played a critical role on the final return leg as thick fog, reducing visibility to 100 yards, closed airfields in England. This prevented Allied fighters from escorting either division to their home bases, while German fighters from JG2 were able to pursue and inflict even more casualties on the dismayed and weary bomber crews as they limped across the normally friendly English Channel waters.

The Aftermath

The battle had been an unmitigated triumph for German defensive plans and a huge blow to US air power. Eaker’s doctrine of unescorted daylight precision bombing had been shattered beyond repair. Out of 260 bombers which pressed the attack, 60 B-17s had been shot down – an appalling loss rate of almost 25%. A further 12 aircraft which made it home were fit only for scrap, and 121 needed repairs. Only 62 out of 260 aircraft were left relatively unscathed. Over 600 men, many of them experienced crewmen, were missing either as prisoners or dead. Wild US claims of first 288, and then 186, enemy fighters destroyed were soon disproved – the Germans lost 38 fighters destroyed in combat and 20 damaged.

The attack on 14 October remained the most important and successful of the 16 Allied bombing raids on Schweinfurt in the course of the war. Albert Speer later suggested that 67% of the plants’ ball-bearing production had been lost – a possibly exaggerated figure. German reorganization and redeployment of factories was so rapid and thorough that further attacks – the next now delayed by four months due to the terrible US losses – were far less successful.

Forever known as `Black Thursday’ in US air force history, the Schweinfurt raid represented the highest percentage loss to any major USAAF task force during the whole wartime campaign. Only with the development of the long-range P-51 Mustang fighter, capable, with its extra fuel tanks, of escorting heavy bombers all the way to such distant targets, did deep penetration daylight precision bombing become a feasible way of waging the war in the air.