The Peruvian ironclad Huascar engages two Chilean vessels, the Blanco Encalada and the Cochrane, during the battle of Angamos on 8 October 1879. Huascar (Peruvian Monitor, 1865)

Peruvian ironclad monitor ram. Designed by England’s Captain Cowper Coles, the Huascar was built by Lairds at Birkenhead. Launched in October 1865, she displaced 2,030 tons and was 219′ × 36′ × 18′. Her single-expansion 1,650-horsepower engine, four boilers, and single screw drove her at a maximum speed of 12.3 knots. Armed with 2 × 10-inch Armstrong muzzle-loading rifles in a revolving turret, she also mounted 2 × 40-pounders. Her crew complement was 170 men. The Huascar had a 4.5″ belt armor and a 5.5″ turret armor. She carried a sail rig, which greatly extended her range.

The Huascar compiled a unique combat record on the West Coast of South America in Peru’s war with Spain, in a subsequent coup d’état, and in the 1879 War of the Pacific between Peru and Bolivia against Chile. She took a leading role in the 21 May 1879 victory at Iquique but was captured in the 8 October Battle of Angamos. Refitted by her Chilean captors, she eventually became a museum ship in Talcahuano, Chile, where she may be seen today.

Warrior (British Navy, Armored Frigate, 1861)

The world’s first iron-hulled, oceangoing warship. Conceived as an armored frigate and not a battleship, the Warrior had a design that emphasized speed—14.5 knots under steam and over 17 knots under steam and sail—and long-range firepower. Her 4.5-inch armor was restricted to a box battery covering the central two-thirds of the ship, leaving the bow and the stern exposed.

Although the Warrior was built in response to the French wooden-hulled ironclad Gloire, which was a seagoing harbor assault ship, the Warrior’s design was developed from the massive wooden frigates of the Mersey-class. The Mersey had been built in response to the United States’s Merrimack type. The hull lines and style of the Warrior were simply scaled up from the wooden ship. Recognizing the impossibility of building longer wooden warships or carrying the weight of armor plate on a hull designed for high speed, the British adopted the iron hull. They were world leaders in this design and created an epochal ship. Displacing over 9,000 tons, the Warrior was the biggest ship afloat after Brunel’s Great Eastern. Her armament of 40 × 8-inch smoothbore and 7-inch rifled guns combined long-range accuracy with the first effective armor-piercing capability afloat. In 1867 she was rearmed with much more powerful 8-inch and 7-inch muzzle-loading rifles.

Begun in 1859, the Warrior entered service in 1861. With her sister, the Black Prince, and others of the type she defeated the French in a naval arms race. This was a critical victory, as if France could build a navy as powerful as Britain’s it could influence British policy in Europe.

The Warrior served in the active fleet until the end of the French Second Empire in 1870, when she went into the reserve. This demotion reflected the reduced threat and her unsatisfactory performance as a fleet unit. After 1863 the British built true ironclad battleships, which did not perform well tactically with the long-hulled frigates of the Warrior type. The long, sharp hulls of the latter made them a poor squadron unit, as they took a long time to respond to the helm. After three decades of growing obsolescence, the Warrior was hulked in 1902; she then served as an engineering workshop in Portsmouth harbor. In 1923 she moved to Milford Haven in Wales, where she served as a jetty at an oil terminal until the 1970s, when she was removed to Hartlepool to be restored to her former glory. In 1986 she returned to Portsmouth to take up a mooring in the harbor, where she remains as the largest historic ship in the dockyard complex. The Warrior survived to be restored because she was built of wrought iron, which is far more durable than steel, to a design that was seriously overengineered. Her hull was inordinately strong, and it has never leaked. This is a testament to the quality of work and materials put into the ship, while her current condition reflects the commitment of major funds and the skill of the restorers.

The celebrated Battle of Hampton Roads started a new era in naval warfare, in which armour was challenged by guns and shells, and which persisted until the development of aircraft and submarines altered combat at sea still further.

The CSS Virginia and the USS Monitor were by no means the first ironclad warships. The first such vessels, built by the French Navy and used in the Crimean War, were floating batteries – barges mounting guns whose sides were covered with iron plates. It was a simple step to add the plates to a steam warship, and the French built the first such ironclad, the broadside ironclad Gloire, one of a class of three ships.

When the Gloire entered service in 1860, the British Royal Navy was the largest fleet in the world. They were aware of what the French were building and were already at work on their own version. Whereas the French ship was a wooden-hulled ship with armour plates arranged in a belt along her sides – like the floating batteries – the British class, the Warriors, were iron-hulled with a similar, if shorter, belt of armour.

The use of armour on warships coincided with a number of other important changes to naval warfare, each change having some influence on the others. The development of naval shell guns, first used at the Battle of Sinope in 1853, seemed to threaten wooden ships. Armour was the counter to this, but the long belts needed to cover the length of a ship’s side were expensive. It was more efficient to put the guns in a turret that could swivel to cover both broadsides of the ship, which reduced the number of guns needed and allowed the armour protection to cover them completely. The first warship to have a turret, the USS Monitor, also was involved in the first battle between ironclad warships, the Battle of Hampton Roads in March 1862.

The cumulative effect of all these changes was ultimately to revolutionize ship design. At one end of this revolution lay the Battle of Sinope, fought between ships clearly resembling the battle fleet led by Lord Nelson at Trafalgar; at the other end lay HMS Colossus, which entered service in 1886 and was a turret ship almost completely without masts.

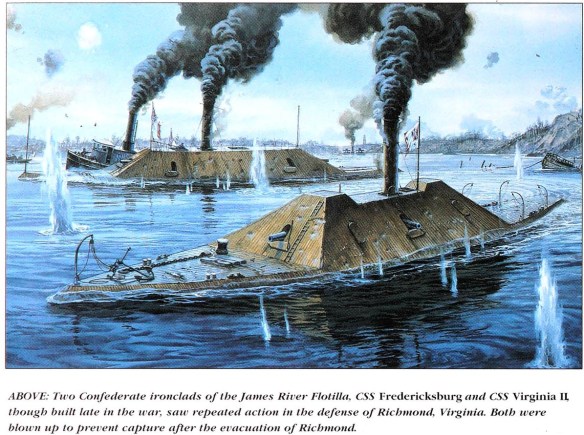

Although the American Civil War was the first conflict to feature a battle between ironclads, the lack of a significant iron industry in the Rebel states, and of any substantial pre-war navy, meant that most battles involving ironclads involved no more than one or two Rebel ones. The main naval battles all involved a fleet attacking a defended port, such as the battles of New Orleans (1862), Mobile Bay and Charleston (both 1864). The first battle between fleets of ironclads occurred in European waters, during the Seven Weeks’ War in 1866 which involved Austria, Prussia and Italy. The Italians had 12 ironclads, the Austro-Hungarians seven. Since gunfire seemed to lack the penetration against armoured vessels sufficient to sink them, success came from ramming enemy ships. The Austro-Hungarians sank two of the Italian ironclads, while suffering no losses, although ships on both sides were badly damaged by gunfire. The Austro-Hungarians’ ramming tactics influenced naval warfare for decades after.

There were few battles involving ironclads in the years that followed, although those that did occur were carefully studied. One engagement, the Battle of Callao, between Peru and Spain, resembled those of Mobile Bay or Charleston in the American Civil War, with a fleet of ocean-going ships attacking a defended port. Both sides had ironclads, but these did not engage each other heavily. In 1877 a battle between two British wooden warships and the mutinous crew of Peruvian ironclad Huascar ended in a draw. The effectiveness of iron armour was clear. Over 400 shots were fired at the Huascar, 50 struck her, but only one penetrated the armour. Peru was involved in the next major actions involving ironclads, in the War of the Pacific (1879-84). The Huascar engaged her Chilean opponents in two battles, the naval Battle of Iquique and the Battle of Angamos. Only the second involved ironclads on both sides and ended with the capture of the Huascar, which was heavily outnumbered six ships to one.

The lack of much combat meant that different theories were applied to ship design, making the Ironclad Era one of the most fascinating to look at in terms of sheer visual variety. The arrangement of the guns was a major matter for debate. Some ships were fitted with turrets, while others had either a broadside battery or some kind of central area known as a barbette or citadel, with the upper deck often considerably narrower than the main deck to allow a degree of gunfire forward. Sailing rigs were not retained out of love of tradition, as is sometimes implied. For most ships, the availability of coal to feed their boilers was by no means assured if they were far from their home ports, so sails provided extra motive power that might otherwise have been lacking.

By the time the Huascar was captured, the revolution in naval affairs had advanced further. The advantages of iron hulls over non-iron ones were well established – the main disadvantage lay in the great weight of iron, which kept the speeds of ships low. However, steel provided a lighter alternative to iron, with most of the same advantages, and naval shipbuilders began adopting steel hulls for their designs.

The first large steel-hulled ship was the French battleship Redoutable, which was completed in 1878. The first naval action involving a steel warship was fought during a civil war in Brazil in April 1894, when a torpedo sank the battleship Aquidaban during a night action. Later that same year came the first battle between steel warships, during the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, when two small squadrons fought off the island of Phung-Do in the Yellow Sea in July 1894. The Japanese sank one vessel and damaged the other. The result was never in doubt, for the Japanese ships were more modern. A larger fleet engagement occurred in September at Yalu, when the Japanese defeated a Chinese fleet containing two battleships, although at heavy loss to themselves.

Development of the Torpedo

During the 1861–1865 U.S. Civil War, mines anchored underwater or mounted at the end of boat spars and detonated by contact (or electricity) were known as torpedoes, after an electric-shock catfish by that name. In the 1870s and 1880s, however, John Ericsson experimented with a steam-powered torpedo connected to the mother ship by a hose. This underwater, compressed-air-powered explosive device with dynamite filler reached a speed of 61 knots, but had a range of only 100 yards. Ericsson also worked on an electric-powered torpedo, as did American Robert Lay. Both types were controlled by an electric cable extending from the ship.

More successful was the less complex flywheel-powered torpedo developed in 1870 by John Adams Howell of the U.S. Navy. Over the next quarter century its speed increased from 8 to 30 knots and its range doubled to 800 yards. In the 1890s the United States also tested rocket- and steam-powered torpedoes. All such self-propelled weapons, totally disconnected from the launch vessel, were called “auto-mobile,” “locomotive,” or “fish” torpedoes.

The most successful torpedo, however, was developed in Fiume (then part of Austria) in 1868 by Austrian Giovanni Luppis and Englishman Robert Whitehead. That weapon, powered by compressed air, reached a speed of six knots and carried 300 pounds of dynamite a distance of 200 yards. A virtually identical weapon was produced soon after by the Schwartzkopff Company in Berlin. In 1870 Whitehead returned to England and sold his manufacturing rights to the Royal Navy. However, Whitehead torpedoes were also manufactured in Italy and France by the time of his death in 1905. Their speed had advanced to 29 knots, and the torpedoes carried 200 pounds of explosives for 6,000 yards. Carried by inexpensive small craft known as torpedo boats, they were viewed by many nations, including France, as the weapon to counter the largest naval powers.

By the turn of the century John P. Holland perfected the modern submarine, which he related to the design of the Whitehead torpedo, and which became the vessel now most commonly associated with the torpedo. By World War I torpedo velocity advanced to 40 knots and range to 10,000 yards (at reduced speed).