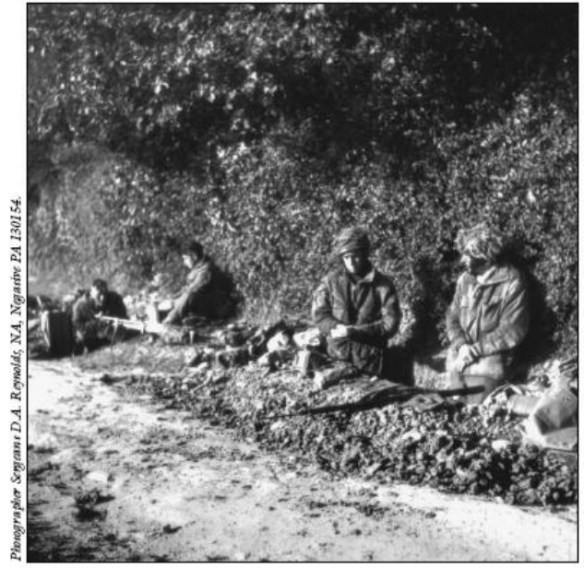

Canadian paratroopers dig in along a road in Normandy, France, 8 June 1944.

Two Canadian paratroopers man a PIAT as they watch for German tanks.

Canada’s new paratroops were darlings of the media. The public image of the paratrooper became such that most people, both civilian and military, believed that airborne soldiers had nerves of steel and that they were virtual supermen. One Canadian reporter wrote: Picture men with muscles of iron dropping in parachutes, hanging precariously from slender ropes, braced for any kind of action, bullets whistling about them from below and above. They congregate or scatter. Some are shot. But the others go on with the job. Perhaps they’re to dynamite an objective. Perhaps they’re to infiltrate through enemy lines and bring about the disorder necessary to break up the foe’s defence, where-upon their comrades out in front can break through. Or perhaps they’re to do reconnoitering and get back the best way they can. But whatever they’re sent out to do, they’ll do it, these toughest men who ever wore khaki. Other newspaper accounts described them as “action-hungry” and as “the sharp, hardened tip of the Canadian Army’s dagger pointed at the heart of Berlin.” One journalist went so far as to write that the Canadian paratroopers were, “Canada’s most daring and rugged soldiers. daring because they’ll be training as paratroops: rugged because paratroops do the toughest jobs in hornet nests behind enemy lines.” Another simply explained that “your Canadian paratrooper is an utterly fearless, level thinking, calculating killer possessive of all the qualities of a delayed-action time bomb.” Even the Canadian Army acknowledged that “Canada’s paratroop units are attracting to their ranks the finest of the Dominion’s fighting men. these recruits are making the paratroops a `corps elite.’” The image of the new paratrooper was played up in newspapers who described paratroopers as virtual supermen.

Although the Allies had established themselves along the Normandy coast and were in the process of reinforcing the beachhead, the Germans had not yet thrown in the towel. They continued to counterattack along the entire Allied front, looking for a soft spot to exploit. In nearby Bréville, to the north of 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion’s position, the Germans focused enormous efforts. The town had been under constant attack since 7 June. The situation was critical and additional artillery support was called in from the divisional artillery of 3rd British Infantry Division to break up substantial German infantry and armour attacks.

The extra weight of steel lashed and tore at the German attackers, but they would not relent. Sensing a weak seam, the enemy seemed more determined than ever to smash a hole in the Allied line. By 10 June, the Germans had seized most of Bréville. That night, Sherman tanks from a squadron of the 13/18 Hussars and 5th Battalion, 51st Highland Division, arrived to strengthen the Allied line, which was part of the 6th Airborne Division’s sector. The next morning, after a preliminary bombardment, the Highlanders launched an attack against the Germans, who had established well-entrenched positions in and around Bréville. The attack failed dismally. As soon as the Highlanders stepped off for the attack, German mortar rounds started raining down on them. Those not wounded or killed by the flying shrapnel were cut down by the German MG 42 machine guns that swept the ground leading to their positions.

The tanks fared no better. As the first three Sherman tanks clanked down the wooded path towards the enemy positions, they were quickly destroyed by a German self-propelled gun that ambushed them from the flank; its first shot tore the turret off the leading Sherman tank. As the two other Shermans that were following began to rotate their guns to engage the enemy armour, they too were brewed up. In less than a minute the Allies had lost three more tanks. In the end, all that the attack achieved was heavy losses — the battlefield was littered with the burning and smouldering hulks of Sherman tanks and the bodies of British infantrymen and paratroopers.

Buoyed by this success, the Germans quickly decided to capitalize on what they perceived as an advantage. The enemy artillery and mortar fire quickly started again. The deadly barrages were immediately followed by massive infantry attacks, supported by tanks and self-propelled guns. Artillery and mortar shells hammered the Allied positions, forcing the defenders to stay hunkered down and allowing the German soldiers to approach the Allied trenches as close behind the curtain of fire as possible without being fired at. German Mk IV tanks and self-propelled guns appeared on the high ground and lent direct-support fire to the attack by hurling explosive shells at any pocket of resistance in the Allied line. In quick succession, they destroyed all of the defenders’ anti-tank guns as well as nine Bren gun carriers.

By late afternoon on 12 June, the Germans, refusing to ease the pressure, were continuing their attacks. The situation deteriorated to the point that an enemy breakthrough in the Bréville area was imminent. in the Bréville area was imminent. The state of affairs had become critical. If the Germans were successful in breaking through at Bréville then the entire 6th Airborne Division sector, which was already dangerously weak, would be compromised and their ability to contain future German attacks would be doubtful. The Division was now in a critical state — its manpower was already stretched to the limit and reinforcing the sector meant weakening another.

By that time, Major-General Gale, the 6th Airborne Division commander, visited the front lines to assess the situation first-hand. Even though the initial and subsequent German attacks had been contained, he quickly realized that the sector was the weakest link in the 6th Airborne’s defensive front. This was not surprising. From the outset, Brigadier James Hill, the commander of 3rd Parachute Brigade, had warned him about the weak state of defence at Bréville and its surrounding areas. Immediately after the D-Day drop, he had urged Major-General Gale to take whatever action was necessary to remove the Bréville menace. Now Brigadier Hill would have his chance to solve the problem; and, the Canadians would help.

Amazingly, Brigadier Hill was recuperating from a serious friendly fire injury he had sustained on D-Day. After the parachute drop, as he was marching towards his objective area, Allied aircraft conducted a bombing run and accidently attacked their own troops. Hill and his party quickly sought cover in shell holes, but a number of the paratroopers were killed and wounded. Hill suffered a deep wound to his buttocks, but he refused treatment until he had established the defence of his Brigade area. Only days later would he allow the Brigade surgeon to operate on him to sew up his wound. Despite his recent surgery and healing wound, Hill realized the situation was desperate and decided to take matters into his own hands.

Brigadier Hill rushed over to the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion Headquarters to gather all available personnel. Although the Canadians were also under heavy attack, the commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Bradbrooke, felt he could hold off the enemy well enough in his sector. He released his reserve force to the Brigadier.

The word was quickly passed on. Captain John P. Hanson and approximately 40 paratroopers from “C” and “HQ” Companies assembled at the Battalion headquarters to receive their orders. Brigadier Hill, a charismatic commander who always led by example, simply smiled at the men and said, “Come along Chaps, nothing to worry about.” He then led his ad hoc force to Bréville in an attempt to stop the German breakthrough.

Captain Hanson, in charge of the small rescue force, remembers his briefing from Brigadier Hill very clearly. The Brigadier pulled the young captain aside and explained in a cheery tone, “Hanson, old man, the Scots on our left are having some heavy going and we will have to go in to help them out.” Seconds later, they were racing to the fight.

The struggle for the Bréville area had developed into the most intense German offensive in 6th Airborne Division’s area since the D-Day drop. The Canadians arrived amidst a raging battle. The terrain was cluttered with smouldering vehicles and exploding ammunition. Bodies were strewn everywhere. The small band of paratroopers immediately deployed in the woods east of the Château de St-Côme. Tree branches snapped off and crashed around them as bullets and shrapnel cut a swath through the foliage. The Canadian paratroopers quickly dug in at the edge of the treeline, occupying some of the hastily abandoned positions of the Highland battalion.

Rummaging through the abandoned positions, the Canadians found three Vickers medium machine guns and plenty of ammunition. They quickly put their newfound firepower to use. The chatter of the Vickers quickly reached a crescendo as the paratroopers hammered the German attackers. “Three Sherman tanks pulled up on our right and stopped in front of our positions,” recalled Private Jan de Vries. “Suddenly, they were brewed up by German self-propelled guns.” As demoralizing as that was, what was worse was that the smoking hulks blocked their field of fire.

Many of the paratroopers were forced to move out to find alternate positions under heavy enemy fire. Throughout, Brigadier Hill hobbled from one position to another, encouraging his young paratroopers. His calmness in the utter chaos around him was inspirational to the Canadians. As the Brigadier approached a trench occupied by Private Michael Ball and his sergeant, an enemy shell exploded over their position. “My sergeant got killed,” remembered Ball. “He got a piece of shrapnel in the head, but Brigadier Hill, never backed down at all.” Hill’s amazing physical courage and love of his soldiers earned him the undying loyalty of his paratroopers.

The battle raged on for hours. At one point, Hill called in naval and artillery fire, which finally silenced the enemy’s tanks and self-propelled guns. Hill ordered the Canadians to clear the woods of enemy men. Savage hand-to-hand fighting was what it took to finally push the Germans back.

The Canadians fought aggressively, stood their ground, and forced larger groups of German infantry to fall back. The tenacious leadership of Hill and Hanson, coupled with the arrival of the paratroopers, lifted the spirits of the other British defenders and succeeded in blunting the German advance. “The Black Watch Battalion was completely disorganized,” wrote Hanson, “and I can safely say that ‘C’ Company saved a complete rout and a split in our left flank.”

The arrival of the Canadian paratroopers actually turned the tide of the battle. The ragged defenders, who had been shelled and battered by relentless German attacks for days and were on the verge of withdrawing, took heart and fought on. In fact, it was the German will that was broken. By 2200 hours that night, the Allies went on the offensive and by first light on 13 June 1944, they recaptured Bréville.

The Canadian paratroopers did not participate in the final assault to recapture the town. Having accomplished their mission of stopping the German breakthrough, they returned to their own position an hour before the Allied attack began; however, only 20 of the Canadian paratroopers made it back to their own lines. Over half of the original group was either wounded or killed in the heavy fighting at Bréville.

The Canadian paratroopers’ first week in Normandy had been gruelling to say the least. After being decimated by the bad drop, each day more paratroopers were lost to German attacks, shelling, and sniping. With each loss came additional responsibilities for those who survived, adding to their fatigue and the risk. There was no denying that combat in the close confined boscage country was intense.

Adding to the difficulty were the warmer than usual weather conditions for that time of year in Normandy. One veteran recalled, “There was a pungent odour that constantly hovered over both sides of this clustered area like a black ominous cloud of death.” There was just no escaping the constant smell of decomposing flesh. It hung in the air — a constant reminder that death lurked nearby. This further tested the endurance of the airborne soldiers.

In the end the Battalion, despite the enemy’s best efforts, held their position. Lieutenant-Colonel Bradbrooke was justifiably proud of his unit’s performance:

The country around Le Mesnil was very close with its ditches and hedges, and it was a perfect position for determined boys like ours. We were just one little pocket out on the end of nowhere. After three days we had 300 men and we held for days against many attacks. The Germans were methodical as the devil but our mortars and machine guns knocked the hell out of them. Between 200 and 300 hundred dead Germans piled up in the fields in front of us and for days we could not even get out to bury them because of incessant sniping.

Brigadier Hill later referred to Le Mesnil as “one of the great battles of the war.” He noted, “In the first eight days I lost in 3rd Parachute Brigade over a thousand chaps and I think 58 officers. It was very, very tough.”

Finally, on 17 June, the remaining 312 exhausted paratroopers of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion were relieved by the 5th Parachute Battalion and sent to a rest area for a brief break to relax and refit. Until that point in the Normandy Campaign, the Battalion had suffered approximately 52 killed, 97 wounded, and 86 captured (all following the poorly dispersed drop). Although the rest was badly needed and greatly appreciated, it was to be short-lived.