The arrival of this squadron of the relief fleet brought an angry reaction from the Jacobites who opened fire on the quay and the city from across the river. Such was the danger to those unloading the vessels that blinds had to be constructed along the quay; these were improvized from casks and hogsheads filled with earth and built up to form a wall. In the course of the night the blinds were tested fully as the gunners over the river maintained a ‘brisk and continued cannonading . . . against the town’.

From the Phoenix those acting as stevedores, men detailed from each of the companies in the city, unloaded 800 containers of meal that had been brought from Scotland and for which a petition had been presented to the Scottish government. Browning’s Mountjoy which could carry 135 tons, had brought ‘beef, peas, flour, biscuits etc all of the best kind’ which had been sent from England. These were all carried to the store houses. This restocking of the stores brought, in Walker’s words, ‘unexpressible joy’ to the garrison which he reckoned had but two days’ rations left ‘and among us all one pint of meal to each man’. Nine lean horses were all that remained for meat – where these came from is not made clear; the last horse had supposedly been slaughtered long since – and hunger and disease had reduced the one-time garrison of 7,500 to about 4,300, of whom at least a quarter were unfit for service. The first issues of food from the newly-arrived provisions were made the following morning and must have been as great a boost to the morale of the garrison and people of the city as the sight of the Mountjoy and Phoenix making for the quay.

The siege was over. Richard Hamilton knew that the arrival of the relief ships would allow the garrison to hold out longer and how he must have rued his decision to countermand de Pointis’ plan for a second boom and to carry out maintenance work on the boom that had been completed. He knew also that Kirke had a strong force on Inch and that this might march for Derry at any time while Schomberg was preparing an even larger force that would soon land in Ulster to link up with Kirke’s contingent and the Enniskillen garrison. There was no alternative but for the Jacobite army to quit Derry. It had failed in its objective with every plan adopted seemingly doomed. On the day following the arrival of the Mountjoy and Phoenix, Ash commented that there was ‘nothing worth note’ although Mackenzie recorded that the Jacobites continued to fire on the city from their trenches.

But the decision to quit was taken that day. According to the writer of A Light to the Blind, the decision was made by de Rosen who

seeing the town relieved with provisions contrary to expectation, and that there was no other way at present to take it, judged it in vain to remain there any longer, and so he commanded the army to prepare for rising the next day, and for marching back into Leinster, and approaching to Dublin.

On 1 August the Jacobite army decamped from Derry. It had lain before the city for fifteen weeks with the loss of some 2,000 men dead, a figure that probably underestimates considerably the true losses. Walker, who wrote that the enemy ‘ran away in the night time, [and] robbed and burnt all before them for several miles’, also estimated the Jacobite dead at between 8,000 and 9,000 plus a hundred of their best officers. The scorched-earth tactic is confirmed by Ash who wrote that the enemy ‘burned a great many houses in the County of Derry and elsewhere’ and that, when he went to visit his own farm on 1 August, he found ‘the roof of my house was smoking in the floor, and the doors falling off the hinges’. Berwick was later to attain notoriety for his use of the same tactic elsewhere in Ireland, and it is possible that he was also advocating its use at Derry. A deserter from Berwick’s camp who arrived at the Williamite base on Inch said that he had been with the duke at Castlefinn when several officers arrived with the news that relief had reached the defenders of the city, An enraged Berwick

flung his hat on the ground and said, ‘The rogues have broken the siege and we are all undone.’ He says also, it was at once resolved to immediately quit the siege, and burn, and waste, all before them; but upon second consideration they have despatched a messenger to the late King James at Dublin, of which they expect an answer. In the mean time, they have sent out orders to all the Catholics to send away all their goods and chattels, and to be ready to march themselves whenever the army moves. It is also resolved to drive all the Protestants away before them, and to lay the country in waste as much as they can.

So it would seem that Berwick was the man responsible for ordering so much destruction. The troops at Inch saw several ‘great fires’ in the direction of Letterkenny, to the south-west, which they believed to be villages set alight by the retreating Jacobites. Under cover of darkness, a company of musketeers, under Captain Billing, crossed from Inch to the mainland near Burt castle and then marched about a mile before surprising a small guard of Jacobite dragoons and securing a safe passage to Inch for several Protestant families with their cattle and whatever other goods were found en route. Confirmation that the Jacobites were quitting the area was provided when several parties of their horsemen were seen ‘setting fire to all the neighbouring villages, which gives us great hopes that they don’t design any long stay in these parts’. Kirke reported that the Jacobites ‘blew up Culmore Castle, burnt Red Castle and all the houses down the river’. By then he had returned to Lough Swilly in HMS Swallow and come ashore at Inch.

According to Walker, some of the garrison, ‘after refreshment with a proper share of our new provisions’, left the city to see what the enemy was doing. Jacobite soldiers were observed on the march and the Williamites set off in pursuit. This proved to be an ill-advised move as they encountered a cavalry unit performing rearguard duty for the Jacobites and the horsemen engaged their pursuers, killing seven of them.

Of course, there had been two wings of the Jacobite army, separated by the Foyle. These made their discrete ways to the nearest point at which a junction could be effected, in the vicinity of Strabane. Retreating from before the city’s western and southern defences, the Jacobites made their way to Lifford, back to the area of the fords where they had achieved one of their few real successes of the campaign. Likewise, those who had formed the eastern wing of the besieging force withdrew to Strabane, although some are known to have moved east towards Coleraine. Strabane appears to have been a temporary stop for the army as the commanders awaited further news. What news they received was not good: the Jacobite force in Fermanagh had been defeated at the battle of Newtownbutler where Lord Mountcashel had suffered the greatest defeat yet inflicted on Jacobite arms in Ulster.

On 3 August news reached the camp at Inch that the main Jacobite army was now at Strabane, and Kirke felt confident enough to send Captain Henry Withers to Liverpool on board HMS Dartmouth with a despatch for ‘King and Parliament [detailing] our great success against the Irish Papists’. Ash recorded that, at Lifford, the Jacobites were in such haste to be away that they ‘burst three of their great guns, left one of their mortar pieces, and threw many of their arms into the lake’. By bursting the guns he meant that the Jacobite gunners had destroyed their weapons; this was usually done by dismounting the barrels, filling them with powder and burying them muzzle down before discharging them. This action had been taken following news of the disaster at Newtownbutler which was the final factor in the Jacobite decision to quit Ulster. In their going they dumped many weapons in the river and left behind many of their comrades who were sick. Between the city and Strabane, some groups of Jacobite grenadiers who were engaged in setting fire to houses were taken prisoner by Williamite troops.

A few Williamites were probably fit enough to take part in such forays outside the town, but it is more likely that the patrols were from the fresh troops who had landed in the city with the Mountjoy, Phoenix and Jerusalem, although they would have numbered only about 120 men. Some foragers from the city brought in a ‘great number of black cattle from the country for the use of the garrison’, but these dairy cattle were restored to their owners the following day. It seems that not everything had been destroyed by the Jacobites and, since these cattle belonged to Williamites, it also appears that those in the vicinity of the city had not suffered too much in the days of the siege. Much of their losses probably occurred as a result of the Jacobite forces venting their anger at failing to take the city.

With the Jacobite army withdrawing, Walker expressed some impatience to see Kirke, whom he described as ‘under God and King, our Deliverer’. He sent a delegation of five men, including two clergymen, to Inch to meet Kirke, give him an account of the raising of the siege, convey the city’s thanks to him and invite him to come and meet the garrison. The latter invitation was superfluous since Kirke would have intended to come to the city anyway. Richards recorded that Walker’s men stayed all night at Inch due to the very wet and windy weather. Following the visit of that delegation, Kirke sent Colonel Steuart and Jacob Richards to the city ‘to congratulate our deliverance’ according to Walker but, according to Richards, to give the orders necessary for repairs to the city and its fortifications. This was a precursor to Kirke’s own arrival which took place on Sunday 4 August. On the same day he had ordered a detachment of seventy-two men from each regiment ‘to march over to Londonderry, there to encamp and make up huts for the several regiments against they arrive’.

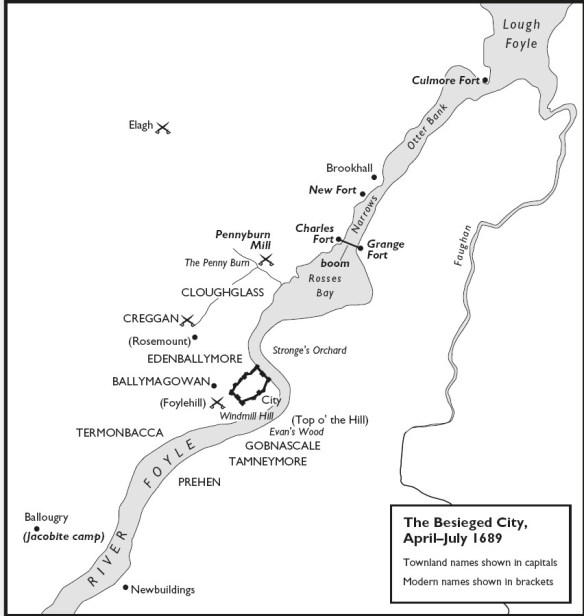

Windmill Hill had been chosen as the site for the encampment of the relieving forces. The local regiments were to remain within the walls, and the two forces were to be segregated to prevent an outbreak of disease among the newly-arrived troops. The camp at Inch was to be abandoned save for the hospital and a small garrison of 200 men with six artillery pieces commanded by Captain Thomas Barbour. Moving the relief force’s supplies and impedimenta required the deployment of the ships to carry them out of the Swilly and around the north of Inishowen into Lough Foyle and hence to the city. That a small garrison was to be left at Inch suggests that there was some concern that not all the Jacobites had departed the region. On the 5th some ‘Irish skulking rogues came back to Muff, Ballykelly, Newtown and Magilligan, and burned houses which had escaped’ the previous depredations. These ‘skulking rogues’ would have been from that part of the Jacobite army that was falling back to Coleraine. (The Muff referred to here is the modern village of Eglinton in County Londonderry, while Newtown is Limavady.6)

Kirke was unimpressed by Derry and its defences, writing that

since I was born I never saw a town of so little strength to rout an army with so many generals against it. The walls and outwork are not touched [but] the houses are generally broke down by the bombs; there have been five hundred and ninety one shot into the town.

The major-general had already had a report from Richards about the state of the city. This had also included the observation that there was ‘little appearance of a siege by the damage done to the houses or walls’. However, Richards went on to report that

the people had suffered extremely, having for 5 weeks lived on horses, dogs, cats etc. They lost not during the whole siege 100 men by the sword, but near 6,000 through sickness and want and there still remained about 5,000 able fighting men in the town, who abound with the spoil of those they have killed or taken prisoner.

When Kirke arrived at Bishop’s Gate he was received with courtesy and some ceremony. There Mitchelburne, who would have already known him, and Walker, with other officers of the garrison, members of the corporation and ‘a great many persons of all sorts’ met him and offered him the keys to the city as well as the civic sword and mace, all of which Kirke returned to those who had presented the individual items. Soldiers lined the streets to receive their deliverer while the cannon on the walls fired in salute. Even the city’s sick, of whom there were many, made the effort to crawl to their doors and windows to see Kirke and his entourage. Mitchelburne and Walker entertained Kirke to dinner which was described as being ‘very good . . . considering the times; small sour beer, milk and water, with some little quantity of brandy, was and is the best of our liquors’. Following dinner he went to the Windmill to look at the camp for his soldiers. Ash noted that he rode on a white mare that belonged to Mitchelburne which the latter ‘had saved all the siege’. Presumably this was ‘Bloody Bones’, the charger gifted to Mitchelburne by Clotworthy Skeffington. One wonders that this fine animal had survived, but perhaps she had been kept outside the city?

As Kirke was preparing to return to Inch, three horsemen arrived carrying letters from the governors of Enniskillen. These brought official news of the success of the Williamite forces under Colonel Wolseley and Lieutenant-Colonel Tiffin at Newtownbutler. Details of the battle were included while, later that night, Kirke also received the news that Berwick was decamping from Strabane and that most of the army that had been before Derry had gone to Charlemont en route to Dublin. Kirke then rode back to Inch while Richards remained in the city to make further preparations for the arrival of the remainder of the relief force. Meanwhile Kirke had invited several of the leading citizens to dine with him on Inch the following day. This might not have been the most convivial of occasions for Walker, since Kirke took the opportunity to suggest that it was time for him ‘to return to his own profession’.

Kirke’s three regiments arrived in the city on the 7th with the major-general at their head; their baggage was en route by sea. Once again there was a rapturous reception, with the defenders coming out in force to give the troops three cheers as well as a salute from their cannon. It also seems that all the garrison’s personal weapons were discharged as part of a feu de joie. And there was another dinner after which a council of war was held to which only field officers were invited. This meeting discussed regulating the local regiments, the civil administration of the city and ‘several other necessary things’, which included the market and cleansing the town. The latter task must have been of almost Herculean proportions. It was further decided that the following day would be one of thanksgiving.

And so, on 8 August, the city rejoiced for its deliverance. There was considerable merry-making but the day began with a sermon preached by Mr John Know, who told his congregation, which included Kirke, of the nature of the siege and ‘the great deliverance, which from Almighty God we have obtained’. That evening the city’s regiments were drawn up around the walls and fired three volleys while the cannon, too, were fired in salute. A proclamation was also issued stating that anyone who was not in the ranks of one of the regiments and had not resided in the city prior to the siege should return to their own homes before the following Monday. Nor were any goods to be taken out of the city without permission. With the Jacobites now far away, the bureaucrats were back in place. And it seemed that the closest Jacobites were at Coleraine ‘where they were fortifying themselves’.

Walker took ship for England the next day, there to produce and have published his ‘true account’ of the siege. Needless to say, this true account would be centred around the activities of Governor Walker, who would thus become the hero of the siege. The London Gazette for 19–22 August carried a report from Edinburgh that Walker had reached that city on the 13th with news that the Enniskilleners, under Colonels Wolseley and Tiffin, but whom he called Owsley and Tiffany, had routed the Jacobites on their retreat from Londonderry and caused heavy losses. This was Walker’s version of the battle of Newtownbutler which, in fact, had been fought between a different Jacobite force from that retreating from Derry and the defenders of Enniskillen. From Edinburgh he made his way to London and was received at Hampton Court by William and Mary; one report suggests that he received £5,000 ‘for his service at Londonderry’. For Mitchelburne, Murray and many others their sole reward was to be thanked for their services.

For those left behind in the city there were some indications of what lay in store for them. All who expected pay for their service in defending the city were told to appear in their arms at 10 o’clock on the following Monday. Whatever they anticipated, they were to be disappointed: no payment was ever made. There was a popular belief among the soldiers that Kirke would distribute £2,000 but ‘they soon found themselves mistaken, not only in that, but in their hopes of continuing in their present posts’. One man who had provided £1,000 to support the city in its travails was the Stronge who owned the land across the river. When Sir Patrick Macrory was writing his book on the siege he was told by Sir Norman Stronge, a direct descendant of that landowner, that he still held two notes, signed by Mitchelburne, promising that the money would be repaid. In 1980 Sir Norman calculated that the IOUs represented, with interest, some £60m. These notes were lost when republican terrorists attacked Sir Norman’s home at Tynan Abbey in County Armagh in 1981, murdering both Sir Norman and his son James before setting fire to and destroying their home.

On the 12th Kirke reduced the garrison’s regiments to four. Colonel Monroe’s and Colonel Lance’s Regiments were amalgamated, Walker’s Regiment was given to Colonel Robert White, Baker’s to Colonel Thomas St John – the would-be engineer of Inch – and Mitchelburne retained the regiment he had commanded throughout the siege, that which had been Clotworthy Skeffington’s. As White died soon after this re-organization his regiment passed to Colonel John Caulfield. No records have survived of the regiment formed by the amalgamation of Monroe’s and Lance’s Regiments, and so it would seem that the new unit had a very brief existence. This might have been less than a month, as Kenneth Ferguson notes that a royal warrant of 16 September adopted only three Londonderry battalions; Kirke was ordered to treat unplaced officers as supernumerary until vacancies could be found for them. Caulfield’s Regiment had been disbanded by 1694 and the surviving regiments, Mitchelburne’s and St John’s, were disbanded by 1698 by which time the War of the League of Augsburg had ended. In contrast, those regiments formed in Enniskillen had a much longer existence with three of them surviving, albeit in much changed form, to this day: Tiffin’s Regiment was the progenitor of the present Royal Irish Regiment while today’s Royal Dragoon Guards may be traced back to dragoon regiments raised in Enniskillen in 1689. However, in 1693 some survivors of the siege formed part of a new regiment, Henry Cunningham’s Regiment of Dragoons, raised in Ulster. In time, this regiment was ranked as the 8th Dragoons and later as 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars. In 1958 amalgamation with 4th Queen’s Own Hussars created the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars, the regiment that led the coalition advance into Kuwait in the Gulf War of 1991; the Hussars’ leading tank was called ‘Derry’ and the regiment was commanded by a Derryman. Perhaps some of the spirit of Murray’s Horse had passed down the centuries to the men who manned the Hussars’ Challenger tanks.

To return to 1689, Kirke continued his work on reforming the garrison, but he also organized a force to attack the Jacobites at Coleraine. However, when that force, led it seems by Kirke himself, approached Coleraine, the local garrison decided that it did not want to engage in a battle with the butcher of Sedgemoor and the town was abandoned. A plan had been made to destroy the bridge leading into Coleraine, thus at least delaying any Williamite advance if not assisting a Jacobite defence. This had involved coating the timbers of the bridge with pitch which would then be set alight as the foe approached. In the event the Jacobite garrison was so keen to quit the town that the bridge was left standing, those whose assigned task it had been to start the fire showing no heart for the job. The news that Coleraine had been regained reached London at the same time as the news that the town of Sligo had also been abandoned by the Jacobites. The latter information was far from accurate: Sligo did not fall into Williamite hands until 1691, following the battle of Aughrim.

The Williamite army continued its task of clearing Ulster. On 16 August Schomberg sailed from England ‘with a fair wind’ at the head of the main body of the force that was to be deployed in Ireland. At the beginning of September this army was engaged in the siege of Carrickfergus where Jacob Richards was wounded in both thigh and shoulder. Before long most of Ulster was in Williamite hands, with only pockets of Jacobite resistance remaining in the southern part of the province.

The key element in this campaign had been the siege of Derry. Had the city fallen to the Jacobites in April, or failed to hold out as it did, then the Williamite cause in Ulster would have been lost. Enniskillen could not have held out against a Jacobite army no longer distracted by the task of reducing the recalcitrant city and nor would Sligo have been able to sustain a defence for much longer. That the city on the Foyle was the vital element in saving all Ireland for the Williamites was recognized across the three kingdoms. George Walker, the soi-disant governor of Londonderry, was feted in London and took full advantage of the opportunity to further his own reputation with the publication of his book A True Account of the Siege of London-Derry. On 19 November he was thanked by the House of Commons for his services at Londonderry and responded:

As for the service I have done, it is very little, and does not deserve this favour you have done me: I shall give the thanks of this House to those concerned with me, as you desire, and dare assure you, that both I and they will continue faithful to the service of King William and Queen Mary to the end of their lives.

As the tide of war flowed elsewhere the people of north-west Ulster tried to begin their lives anew, safe from the threats that had so recently beset them. But it would be a very difficult task and one in which many of them would not succeed. The scars of those 105 days in 1689 would never fade and the attitude of the government at Westminster towards the survivors would help to ensure that.