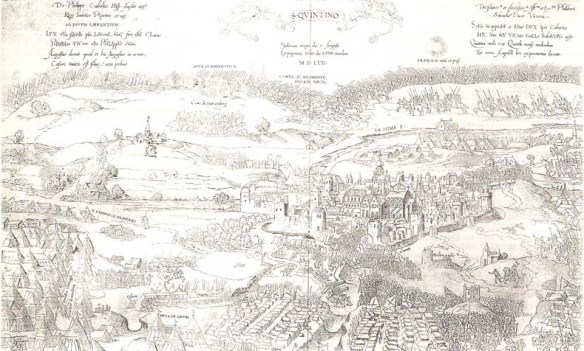

1557 Battle of Saint Quentin. Spanish arquebusiers in street fighting in the suburbs of the town.

The earliest chronogram found depicts the siege and battle of Saint Quentin in 1557.

Saint-Quentin, Battle of 10 August 1557 English forces fighting with the armies of Philip II of Spain, husband and ally of Mary I, assist in defeat of French army outside besieged French town of Saint-Quentin.

The Battle of Saint-Quentin of 1557 was fought at Saint-Quentin in Picardy, during the Italian War of 1551–1559. The Spanish, which is to say the international forces of Philip II’s Spanish Empire, who had regained the support of the English whose Mary I of England he had married, won a significant victory over the French at Saint-Quentin, in northern France.

The king of Spain in 1556, when he took the throne over from his father, was aged twenty-eight, a man of few words, of medium build, with fair hair and blue eyes. A devotee of hunting and jousting, cultured, serious and deeply religious, he had spent nearly five years travelling through the principal countries of Europe. Regent of Spain since 1543, when he was aged sixteen, he had accumulated ample experience of the problems of government. After several months in England with his wife Mary Tudor, he crossed over to Brussels to receive from his father in 1555 the territories that from then on constituted his inheritance. Charles did not abdicate from Sicily, Naples and Milan, for these realms already belonged to Philip, who had been given the right of succession to the dukedom of Milan as early as 1540 and was invested as its duke three years later. He also received the crown of Sicily and Naples the day before his wedding to Mary Tudor in 1554. It only remained to give the prince the Netherlands, the Crown of Castile (which included the New World), and that of Aragon together with Sardinia. Philip’s right to rule remained the same as that of his father: it was dynastic, that is, based purely on the principle of inheritance in the family. His title in all his European territories continued to be dynastic. But under him a fundamental difference began to operate for the first time. Because the territories he controlled were centred on the Mediterranean, very quickly their political focus moved to Spain, since the king chose Spain as his centre. He stayed on four more years in the Netherlands, where a new war with France, provoked principally by events in Italy, demanded his attention. But it was Spain, and the men of Spain, that from now on began to make the decisions and wield the power.

While a French army invaded Italy to attack Milan, another invaded the Netherlands. By July 1557 Philip in Brussels had assembled a defensive army of thirty-five thousand men, commanded by Emanuele Filiberto, the duke of Savoy, and William of Nassau, Prince of Orange, with cavalry under the orders of Lamoral, Earl of Egmont. Of Philip’s total available forces (not all of whom took part in the battle) only twelve per cent were Spaniards. Fifty-three per cent were Germans, twenty-three per cent Netherlanders, and twelve per cent English. All the chief commanders were non-Spaniards. The king threw himself with energy into the campaign.3 In the last week of July he was busily arranging for the scattered Italian and German troops under his command to rendezvous at St Quentin. His duties made it impossible for him to go to the front, but he insisted to Savoy that (the emphasis is that of the king himself in his letter) ‘you must avoid engaging in battle until I arrive’. On 10 August, the feast of St Lawrence, the Constable of France at the head of some twenty-two thousand infantry and cavalry advanced upon Savoy’s positions before St Quentin. The town was of crucial importance to the Netherlanders, both for blocking the French advance and for clearing the way to a possible march on Paris. Unable to avoid an engagement, Savoy counter-attacked.

In a short but bloody action the army of Flanders routed and destroyed the French forces, which lost over five thousand men, with thousands more taken prisoner. Possibly no more than five hundred of Savoy’s army lost their lives. It was one of the most brilliant military victories of the age. Philip’s friend and adviser Ruy Gómez remarked that the victory had evidently been of God, since it had been won ‘without experience, without troops, and without money’. Though Spaniards played only a small part in it, the glory redounded to the new king of Spain, and Philip saw it as God’s blessing on his reign. The Spanish contingent in the battle had constituted only one-tenth of the troops, thereby undermining the classic view that St Quentin was a Spanish victory. The Spanish troops may have been few, but they were more effective than the rest, making it a Spanish victory. In any case, the victory belongs to him who paid for the battle, and that was Spain. One way or the other it must have been, and therefore was, a Spanish triumph: ‘the battle was won by the Spanish contingent’

The French were forced into peace negotiations, and peace talks, which began late in 1558, ended with the signing of a treaty in April 1559 at Cateau-Cambrésis.

Philip returned home to Castile in September 1559, confident that the peace he had just made with the French would be a lasting one. ‘It is totally impossible for me to sustain the war’, he had written earlier that year. There were serious financial problems that needed to be resolved. In 1556 – omen of much graver events to come – a Spanish regiment in Flanders had mutinied when not paid. ‘I am extremely sorry’, Philip wrote to the duke of Savoy, ‘not to be able to send you the money for paying off this army, but I simply do not have it. You can see that the only possibility is to negotiate with the Fuggers.’ The costs of war, not only in the Netherlands but also in Italy, were already insupportable.

Cateau-Cambrésis promised a pause. It was the end of the long dynastic conflict between the houses of Valois and Habsburg, and was sealed by Philip’s marriage to the daughter of Henry II of France, Elizabeth. Seeing the vast territories he controlled, however, other powers feared the king’s intentions. The Venetian ambassador at his court took a more hopeful view. Philip’s aim, he reported, was ‘not to wage war so that he can add to his kingdoms, but to wage peace so that he can keep the lands he has’. Throughout his reign, the king never veered from this idea. ‘I have no claims to the territory of others’, he wrote once to his father. ‘But I would also like it to be understood that I must defend that which Your Majesty has granted to me.’ He stated frequently and firmly to diplomats that he had no expansionist intentions. He employed officials who made clear their opposition to policies of aggression. On the other hand, the realities of political life made it inevitable that he should almost continuously be drawn into war situations, both defensive and aggressive. There were also serious problems to be dealt with, above all the debts accumulated by his father. The financial arrears in Flanders were very bad, he admitted to his chief minister there, Cardinal Granvelle, but ‘I promise you that I have found things here worse than over there. I confess that I never thought it would be like this.’

Notes:

Henry Kamen, Philip of Spain (1997) gives a brief account based on contemporary sources, noting that Spanish troops constituted about 10% of the Habsburg total. Kamen claims that the battle was “won by a mainly Netherlandish army commanded by the non-Spaniards the duke of Savoy and the earl of Egmont”. Kamen, Henry: Golden Age Spain. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 023080246X, p. 28.

On the other hand, Geoffrey Parker states that Spanish troops were decisive in defeating the French at St. Quentin owing to their high value, as well as in defeating the Ottomans at Hungary in 1532 and at Tunis in 1535, and the German protestants at Mühlberg in 1547. Parker, Geoffrey: España y la rebelión de Flandes. Madrid: Nerea, 1989. ISBN 8486763266, p. 41