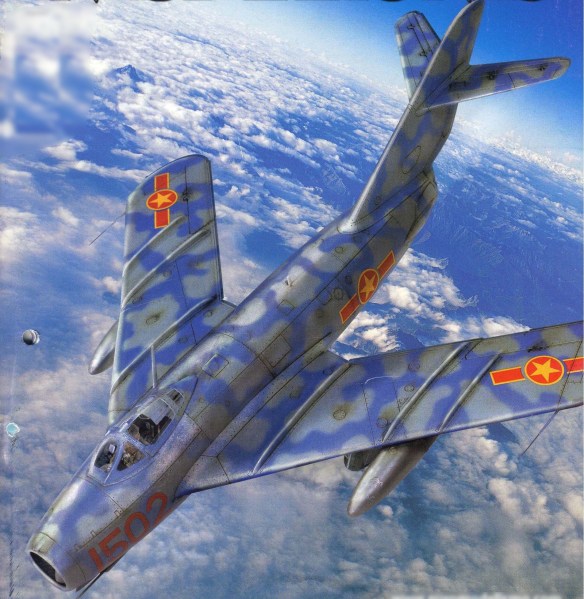

A VPAF MiG-17 dives.

A series of fighter planes, named after the Soviet aircraft design team of Mikoyan and Gurevich. Both Soviet-made MiGs and Chinese copies are referred to as MiGs. The MiGs used by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) were typically armed with cannon (23-mm or 30-mm) and/or short-range Atoll heat-seeking missiles.

The MiG-17, sometimes called Fresco by the Americans, was a small, short-range fighter. It was not very fast but could turn more tightly than the American fighters. Some of those used by the DRV were made in China, under the designation Shenyang J-5. When the United States launched its first air strikes against North Vietnam, Operation Pierce Arrow, on August 5, 1964, after the Tonkin Gulf incidents, there were no MiGs in North Vietnam, but a group of DRV pilots were being trained in southern China to fly MiG-17s. They flew back to Vietnam in their MiGs on August 6. The first success against U.S. aircraft was on April 4, 1965, when two MiG-17s shot down two F-105s near the Ham Rong Bridge in Thanh Hoa province. The first U.S. success against the MiGs was on June 17, when two F-4B Phantoms shot down two MiG-17s.

The MiG-19, sometimes called Farmer by the Americans, was not quite so maneuverable but considerably faster. The DRV only acquired a few MiG-19s during the war, some or all of which were made in China under the designation Shenyang J-6.

The MiG-21, sometimes called Fishbed by the Americans, began to arrive in late 1965 and became available for combat in February 1966. It was faster than the MiG-17 but less maneuverable, and also gave its pilot a much more restricted field of vision. The MiG-21 was the main DRV fighter in the late stages of the war.

MiG-17 SWANSONG

The seemingly ceaseless series of American air raids on Noi Bai, Kep, Kien An and Hoa Lac airfields between January 1967 and March 1968 eventually had the desired effect of all but grounding the VPAF by the early spring. Some 17 MiG fighters and three helicopters had been destroyed in these attacks, as well as a number of fuel tankers. Buildings and aircraft handling areas had also been badly damaged. The four key bases were put out of action on 36 separate occasions, totalling 120 days during the 15-month airfield offensive.

Despite these raids, Tho Xuan in Thanh Hoa Province was completed in early 1968, which meant that the VPAF could now operate from here in defence of the southern front. The bomb-damaged airfields at Vinh, Dong Hoi, Cam Thuy (in Thanh Hoa Province), Anh Son (in Nghe An Province) and Gat (in Quang Binh Province) were also rebuilt. Later, the airfields at Tho Xuan, Vinh, Anh Son and Dong Hoi received new communications systems and additional runways. Closer to the capital, the VPAF command concentrated on improving three main airfields at Hanoi, Gia Lam and Noi Bai, as well as organising support command stations at Hoa Lac, Kien An and Tho Xuan. The forward command remained in Military District No 4, whilst Tho Xuan airfield was expanded to become both a major VPAF base in its own right and home for the increased activities planned to the south of the country.

In May, the Commander-in-Chief Nguyen Van Tien, Chief of the General Staff Tran Manh, his deputy, Nguyen Phuc Trach and other high-ranking VPAF officers visited Military District No 4 to assess the state of its airfields, study the weather conditions and consider enemy tactics. The construction of new airfields was ordered, together with the re-construction of existing ones. The few serviceable aircraft were regularly subjected to temporary deployments, to Noi Bai, Gia Lam, Kep, Hoa Lac, Kien An, Tho Xuan and Vinh, according to operational requirements.

Between the end of 1967 and May 1968 many groups of newly graduating pilots returned home from the Soviet Union and from the air force school at Xiangyun, in China’s Yunnan Province. Among them were 50 MiG-17-qualified and 30 MiG-21-qualified pilots whose arrival increased the number available for frontline duty.

In the six months from April 1968, the Americans flew 79,000 missions against Military District No 4 from Lam River, in Nghe An Province, to Gianh River, in Quang Binh Province. Units of the 921st and 923rd FRs not involved in the defence of Hanoi played an active part in defending the district’s transport routes, as well as participating in battles in South Vietnam and Laos. In addition, preparations were made for future land and sea battles.

The Americans, however, felt that the Vietnamese pilots in Military District No 4 were not able to fight effectively, and therefore attached no great importance to their operations. The VPAF also suffered from the close proximity of US Navy carrier groups to this long and narrow region of the country that was hemmed in by mountains on one side and the sea on the other. The weather was also generally bad and unpredictable.

In early April 1968, as part of the VPAF plan to conduct operations over Military District No 4, the 923rd FR sent two MiG-17s down to Vinh airfield. They were soon spotted by the enemy, however, the Americans mounting more than 100 bomber sorties in a savage raid on the airfield. Both MiGs were so badly damaged that they could not be flown again, the jets subsequently being broken up and useable parts transported to Hanoi by truck.

From late 1967, the 923rd FR had operated a supplementary command station at Tho Xuan airfield under the leadership of Lam Van Lich and Mai Duc Toai. By early May 1968, the fighter regiment had completed its preparatory work to allow it to fly combat sorties over Military District No 4. It was during a major engagement on 7 May north of Vinh that the Americans became aware that MiG-21s were now operating over Military District No 4. Both a MiG-21 and an F-4B from VF-96, embarked in USS Enterprise (CVAN-65), were lost during the clash. In the wake of this action both the US Navy and the USAF began increasing the number of escort fighters assigned to strikes in southern North Vietnam. In order to protect the bombers more effectively, they were assigned to fly in trail formation in two- or four-aircraft sections, ready to react when MiGs were encountered.

Having seen little in the way of aerial action since mid-February due to a shortage of aircraft, the 923rd sent a pair of MiG-17s southward on 14 June after the VPAF HQ command post and VPAF Deputy Commander Dao Dinh Luyen decided to deploy both MiG-17s and MiG-21s to intercept American strike formations. That morning, future aces Luu Huy Chao and Le Hai flew from Gia Lam down to Tho Xuan. After being briefed on their mission by the regiment’s command duty officer, ace Nguyen Van Bay, they were placed on combat standby. That same afternoon, radar stations detected US Navy aircraft 60 km east of Cua Sot. At 1428 hrs, Luu Huy Chao and Le Hai took off from Tho Xuan, the latter subsequently reporting;

‘Our flight flew south, following Route 15. We flew at an altitude of about 300 m, with mountains towering alongside us. After passing Nghia Dan, the ground command post ordered us to climb to 1500 m and head for Thanh Chuong. We were still at 1500 m when the mobile ground control station at Quang Binh alerted us to six F-4s 100 degrees to our left and flying at an altitude of 3000 m. We increased speed, and when we reached 2000 m I reported sighting the target. Chao gave the order, “You attack. I’ll cover you.”

‘Because I’d switched on my afterburner in time, I was able to turn inside and quickly close on an aircraft trying to make a diving turn. With Chao covering me, I turned left and tried to hit an F-4, but with no success. The enemy flight leader made a steep turn. I chose to follow the wingman, turned left and dropped the nose of my MiG to lose some altitude and close up. I fired two long bursts. The F-4 caught fire and crashed near our radar station. I made a left climbing turn to regain my original wingman position.

‘Suddenly, another F-4 popped up ahead of us at an altitude of 1000 m. I closed in before opening fire, but I didn’t hit the F-4, which escaped. Chao recognised the enemy’s attempt to leave on a southeasterly heading. He turned right and found an F-4 dead ahead. He fired a burst at it, but the range was too great and he missed. Turning right, he saw another F-4 heading for the coast. Chao positioned himself behind the target and fired two or three quick bursts. The F-4 blew up and crashed.’

As the rest of the Phantom IIs departed, the MiG-17 pair flew along Route No 15 and landed safely at Tho Xuan. US Navy records do not confirm these losses, however.

Since the deployment to Military District No 4, both the 921st and 923rd FRs had emerged victorious from three successive aerial battles, claiming four US Navy Phantom IIs destroyed (only two were confirmed by US Navy records). Once they had recovered from the surprise of encountering MiGs so far from their northern bases, the US Navy in particular began employing new tactics against the VPAF fighters. It assigned a larger number of F-8 Crusaders to conduct fighter missions and deception operations designed to lure MiGs into engaging them. Usually flying in step formation, with extended separation between aircraft to facilitate splitting up to attack opposing fighters, the F-8 pilots also tried to lure the MiGs into flying over the Gulf of Tonkin within range of missile-armed warships. Finally, they exploited locations with parallel mountain ranges, enabling them to fly into North Vietnamese airspace at low altitude without being detected by radar.

These tactics paid dividends when, on 9 and 29 July, the 923rd FR lost its two most-experienced MiG-17 pilots in combat with F-8s. The unit had established a number of visual observation posts in the Cam Bridge and Vinh airfield areas in an effort to negate the new tactics being used by the US Navy. The 923rd had also formed a forward combat element headed by deputy CO Le Oanh and ground control officer Le Viet Dien. Nguyen Phi Hung and Nguyen Phu Ninh were sent to Tho Xuan on 9 July to intercept the low-flying fighters, both pilots being ordered to covertly take off and then circle over Thung Nua Mountain awaiting further orders.

The pair took off and followed Highway 15 at an altitude of 150 m, and after passing Nghia Dan GCI informed them of two F-8s flying over the Cam area. Heading for Thanh Chuong, Ninh spotted the Crusaders ahead and at 45 degrees to the right of them. As they climbed to 1500 m Hung ordered Ninh to attack, the latter immediately switching on his afterburner and turning in hard. The two F-8s also went in to afterburner and turned for the mountains. As Ninh continued the chase, the F-8s split up. Ninh pursued the Crusader that had turned to the left, firing three cannon bursts at it – his shells hit the top of the jet’s fuselage. Ninh then made a hard turn to break away, spotting Hung pursuing another F-8 towards the Gulf of Tonkin as he did so. Nguyen Phi Hung stuck with his opponent and his burst of cannon fire hit the F-8, which he claimed dived into the sea (according to US Navy records, no F-8s were lost on this date).

The command post then ordered the MiG pair to head for home, but during their return flight they were intercepted by more F-8s over Nghia Dan. Hung told Ninh to continue back to base, then turned around to attack their pursuers. All alone, low on fuel and almost out of ammunition, Hung spotted one of the F-8s launching a missile at his MiG. Ninh, meanwhile, attempted to rescue his leader, but after failing to find Hung he descended to lower altitude before returning to Tho Xuan. Hung avoided two enemy missiles but his aircraft was hit by the third. Immediately turning back towards the coast, he was too low to eject and was killed. By shooting down the F-8 over Ha Tinh, 25-year-old 1Lt Nguyen Phi Hung had scored his fifth victory and had, briefly, become an ace. He had then been shot down by F-8E pilot Lt Cdr John Nichols of VF-191, embarked in Ticonderoga.

The US Navy had another tactic up its sleeve when it came to dealing with increased MiG activity in Military District No 4. The idea was that when VPAF jets were encountered, a flight of F-8s would try to lure them out over the Gulf of Tonkin, where another flight of Crusaders would be lying in wait. Such tactics were employed on 29 July, when a large formation of US Navy strike aircraft, escorted by fighters, attacked transport and other targets at Thanh Chuong, Vinh and Nghe An. In response, VPAF HQ ordered its fighter pilots to defend Route 7 and the Duc Tho and Gianh ferry crossings.

According to the Vietnamese plan, the MiG-17s would fight at low altitude while MiG-21s engaged other enemy aircraft at high altitude. At 1016 hrs command duty officer Dao Dinh Luyen ordered the primary MiG-17 flight of Luu Huy Chao, Hoang Ich, Le Hai and Le Si Diep to take off and head for Nghia Dan, in Nghe An Province. Four minutes later the MiG-21 pair took off to provide support and cover for the mission. Complete radio silence was maintained.

The MiG-17s climbed to an altitude of 2000 m, at which point Chao spotted F-8s four kilometres away. The MiG-17s duly engaged eight Crusaders in a hectic dogfight. While Chao was chasing one of the American fighters he spotted another aircraft flying across his nose from left to right. He immediately turned towards it and fired from a range of 400 m. His shells hit the F-8’s nose. He fired a second burst until his ammunition was exhausted. Chao broke off the engagement and turned away hard. When he rolled his aircraft back to level flight in order to see what was happening he spotted a missile streaking towards Hoang Ich’s MiG. Chao shouted over the radio for Ich to turn hard to avoid the weapon.

Le Hai was also in the thick of the action, as he recalled years later;

‘I spotted an F-8 making a left-hand turn and manoeuvred hard to turn inside him. When the range was right I fired my first burst, but my shells went behind his tail. I fired a second burst and the shells hit the F-8, which rolled completely upside-down. I broke away and saw another F-8 flying underneath and parallel to me. I immediately rolled inverted and dived in pursuit of the enemy aircraft. When I had a stable view of the jet in my gunsight I fired a burst from my cannon but soon ran out of ammunition. The F-8 fled towards the Gulf of Tonkin. I returned to Tho Xuan airfield.

‘We lost our comrade Le Si Diep in that battle. He’d just returned from hospital after being wounded so hadn’t yet recovered his strength. For that reason, he was left behind when we turned sharply. Just as I took aim and was preparing to fire at the rearmost F-8, I heard Chao’s voice shouting, “Eject! Eject!” Looking back, I saw that Diep’s MiG had turned into a ball of flames but I didn’t see his parachute open.’

The F-8 claimed by Le Hai represented his fifth victory, making him an ace according to VPAF records. US Navy records, however, did not confirm that any Crusader had fallen victim to a MiG. Fellow ace Luu Huy Chao also claimed an F-8 destroyed. Le Si Diep’s fighter had been hit by a missile launched by Cdr Guy Cane in an F-8E from VF-53, embarked in Bon Homme Richard. Diep had tried to level his wings and climb but his MiG-17 crashed northwest of Tan Ky, in Nghe An Province. 1Lt Le Si Diep ejected but it was an unsuccessful escape, and he was listed as killed in action.

On 13 August the VPAF-ADF issued order 730/TM-QC signed by Col Dang Tinh, command CO, concerning the organisation of air force units, including the 923rd FR. The regiment was reinforced with additional personnel for its combat, logistical, communications, ground control and technical groups. This took its total complement to more than 400, including 80 pilots. The regiment subsequently organised 195 training days, during which nearly 4000 takeoffs were made and more than 1500 hours flown. In addition, there were 120 nocturnal flights totalling 20 hours. To improve its infrastructure, the regiment built 198 bunkers to provide protection against cluster bombs, as well as three cast-concrete shelters for personnel, aircraft and equipment.

From the end of the year, following an order from the MoD, the VPAF’s presence in Military District No 4 was reduced to a token force. This followed in the wake of President Johnson’s announcement on 1 November of a unilateral cessation of bombing by US forces, thus signalling an end to the long-running Operation Rolling Thunder. The VPAF could now take stock of what it had achieved. In the 1305 days of the US offensive (2 March 1965 to 2 November 1968) the VPAF had flown 1602 sorties and claimed 218 aircraft of 19 different types destroyed. Against the well-trained and numerically superior American forces, the VPAF, with fewer pilots and aircraft, had gradually developed its proficiency so that losses had been reduced as lessons were learned. The MiG fighter regiments had managed to provide a satisfactory response, with an effective defence of both Hanoi and Military District No 4. North Vietnam had started with 36 pilots and 36 MiG fighters, and by 1968 it had two fighter regiments with double the number of fighter pilots and five times the number of aircraft.