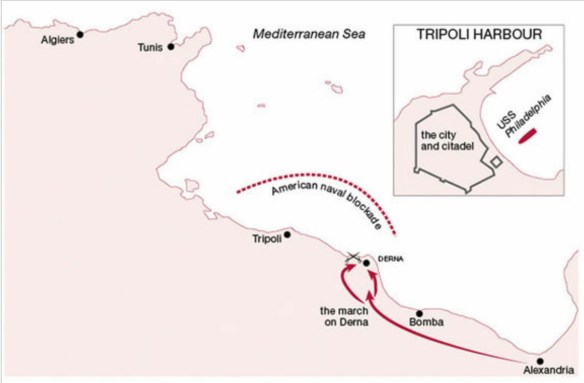

Eaton and O’Bannon’s march on Derna split into a classic pincer manoeuvre to take the town. At the top right can be seen a plan of Tripoli port, showing the location of the grounded USS Philadelphia and the scene of Decatur’s daring raid.

During the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), the shipping of the American colonies was still under the protection of the British Royal Navy and, after the alliance with France in 1778, French ships also acted as guarantors of American cargoes. At that time the greatest threat to American and European shipping came from the corsairs of the Barbary Coast, where pirates enjoyed the support of Muslim North Africa, namely the sultanates of Morocco and Algiers, and the principalities of Tunis and Tripoli. Ruthless piratical crews kept up an unrelenting offensive at sea against all merchant traffic, taking booty and slaves as they chose. The Muslim rulers who launched these proxy raiders enjoyed a lucrative share of the profits and justified their criminal activity as part of a more laudable struggle against all infidels. The rogue states’ wealth, and their remoteness from the centre of the Ottoman empire, to which they owed a nominal suzerainty, meant that they were a law unto themselves.

For decades the Europeans had attempted to contain the problem and the Knights of Malta had been specially commissioned by the Catholic Church to defend the continent against the Turks. Younger knights had, nevertheless, chosen to wage war against the Barbary pirates. In doing so the knights amassed considerable booty and wealth, a fact which caught the attention of the ambitious Napoleon Bonaparte in the 1790s. Napoleon’s actions in the Mediterranean were to have severe repercussions for the nascent United States. He planned to take control of Egypt as a staging post against the British in India and Southeast Asia, and designed his own imperial dominion to replace them. In 1798, Napoleon seized Malta and stripped the island of its wealth. At a stroke, Europe’s southern coastline was once again vulnerable to waves of Barbary corsairs.

At first there seemed no immediate threat to American interests because the United States had shared a close, if informal, amity with Morocco since the latter opened its ports to US ships in 1777. The United States also paid yearly tributes to the Barbary nations, and ratified these informal relations by signing treaties with Morocco (1786), Tripoli (1796) and Algeria (1797). These payments and agreements did not, however, stop the corsairs taking men and ships hostage and demanding ransoms, payments that added a further financial burden. Thomas Jefferson, America’s ambassador to France, wanted to revoke the treaty and advocated building up a navy to patrol the sea lanes instead. However, many in Congress, believing that Americans should focus on the development of their huge hinterland, marginalized the Atlantic and Mediterranean trade routes, and opposed the creation of a large navy.

The Barbary (a corruption of the term ‘berber’) corsairs, had been raiding southern and western Europe for 200 years, seizing ships’ cargoes and enslaving Christians. Those who resisted were treated with considerable cruelty and summarily executed. Such was the scourge that sections of the Mediterranean coastline were depopulated, and it is estimated that 800,000 Europeans were taken into captivity. By the late eighteenth century, however, more powerful navies began to check the activities of the Barbary raiders. English and Dutch fleets had inflicted significant defeats on the Barbary corsairs and Tripoli and Algiers were subjected to bombardments. Despite this, slave-raiding and attacks on merchant ships continued.

In 1801, Yusuf Pasha Karamanli of Tripoli demanded a substantial increase in tribute from America, but the election of Jefferson as president marked a change in foreign policy and he refused to pay. Tripoli promptly declared war and Jefferson sent several frigates into the Mediterranean. In August, the USS Enterprise intercepted the corsair vessel Tripoli and captured her. Despite this, it was not until 1803, when Commodore Edward Preble maintained a blockade of the Barbary ports and made sorties against their harbours and ships, that hostilities began in earnest. The war did not begin auspiciously for the Americans. The naval blockade, though attracting the support of Sweden, proved ineffective. A series of setbacks then damaged the Americans’ position. The personal secretary of the British Governor of Malta was killed in a duel by an American captain, which so soured relations with the United Kingdom that Preble was deprived of an important nearby base for resupply. In early 1803, an accidental explosion aboard an American ship killed 19 men. In May that year, a large squadron of American warships was assembled and set out for Tripoli to destroy the Corsairs’ fleet at anchor. Large shore guns protected the Barbary fleet, which meant that Marines had to be landed close to the walls of the city. They managed to set fire to many of the ships, but large crowds of civilians assembled and showered the Americans with stones and harassing fire. One group of Tripolitans ran the gauntlet of the withdrawing Americans and their covering squadron to extinguish the fires on their ships.

Early in 1804, the Americans’ luck began to change. The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies declared war on Tripoli, which gave them the support of small, manoeuvrable gunboats. On 3 August, an American-led combined force made another attack, bombarding Tripoli at close range. The Americans aboard the smaller gunboats used their speed to catch up with the swift Barbary vessels, boarding them and engaging the pirates in hand-to-hand combat. After destroying part of the port’s fortifications, a large mosque and several gunboats, the squadron withdrew.

The following year, in one of these operations, the USS Philadelphia ran aground in Tripoli harbour and was soon under intense gunfire from shore batteries. Tripolitan ships joined the bombardment and, despite their desperate efforts, the crew were unable to refloat the warship. Captain William Bainbridge took the difficult decision to capitulate in order the save the lives of his men, a considerable risk since so many captives of the Barbary pirates had been forced into slavery. The men were taken ashore to learn their fate. There was a chance that the ship could be refitted and used as a powerful weapon against the Americans, but in fact the Philadelphia, stuck fast, was converted into a platform for a Tripolitan gun battery.

It was under these circumstances that a daring plan was conceived among the American fleet. Stung by the surrender of the Philadelphia to their enemies, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur led out a small detachment of Marines to recover the ship or, at least, to put her out of action. The odds of success were very small, and indeed the chances of Decatur and his men surviving the raid seemed slim. The Tripolitans were alert to the threat of American vessels sailing into the harbour, and had guns that ringed the port. They possessed a sizable garrison that could reinforce any part of the city. Nevertheless, the men set out during the night of 16 February 1804, using the captured ketch Mastico – appropriately renamed the USS Intrepid – to disguise their approach.

The deception plan succeeded and they sailed into the harbour. Decatur’s small party was able to board the Philadelphia and overcame all resistance. It was then a race against time to disable the vessel permanently, before the Tripolitans could react. They set fires, which took hold of the beached ship, and made good their escape, protected by American ships coming in at dawn.

With the Philadelphia destroyed, the Americans made a series of naval assaults on the port in 1804, but none of them neutralized the Tripolitan shipping entirely. Master Commandant Richard Somers volunteered to command the Intrepid as a fire ship and planned to sail it, filled with gunpowder, into the packed enemy ships in a raid even more hazardous than Decatur’s. Tragically, Somers and his crew were all killed before their mission could be completed. Tripolitan guns hammered the Intrepid, and the powder detonated before it could reach the ships in the harbour.

Unable to defeat the Tripolitans decisively from the sea, the American strategy was to initiate a change of regime instead. William Eaton, the former Consul to Tunis, was charged with replacing the ruler of Tripoli, Yusuf Karamanli, with his elder brother and the rightful heir, Hamet. Eaton recruited a force of 500 Arab, Greek and Berber mercenaries at Alexandria and appointed Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon as their American commander. On 8 March the contingent set out to make an arduous 500-mile (800-km) march across the North African desert, knowing that they would have to fight their way through Barbary forces at the end of the odyssey. The 50-day ordeal tested the patience of the mercenaries and several times they threatened mutiny. Nevertheless, in the April of 1805, Eaton and O’Bannon’s force reached the port city of Bomba, 38 miles (60 km) southeast of the Tripolitan port of Derna – their target. At Bomba they made a rendezvous with three American warships. Rested and resupplied, the American-led contingent had the satisfaction of watching these ships shell the defences of Derna, but all knew that this strategically important location would need to be stormed from the landward side.

On 27 April a two-pronged assault was launched. The Arab detachment led by Hamet circled around to the west and began their attack in the direction of the governor’s palace, while O’Bannon, a handful of American Marines and the rest of the mercenaries began a direct assault on the harbour fortress. Alerted to the impending attack, the more numerous defenders had strengthened their position and they managed to repel the first American wave. Eaton himself joined the attack and the ferocity of the second attempt caused the defenders to flee. O’Bannon mounted the ramparts and raised the Stars and Stripes to signal their success to the warships, while his men turned the captured cannon on their former owners. The defenders retreated through the city and were intercepted by Hamet’s Arab mercenaries. The port was taken in just under two hours. The newly instated Prince Harmet Karamanli was so impressed with O’Bannon’s achievements that it is said he presented him with a magnificent curved sword. Later, when he returned to the United States, the Virginia Legislature presented O’Bannon with a similar sword of honour in the curved Mameluke style, and in 1825 the Marine Corps adopted the design as the dress sword for all officers.

Although the battle had been won, the campaign was far from over. Yusuf dispatched reinforcements to Derna, and the port was quickly encircled. Eaton ordered that the fortifications be strengthened but his small contingent could not be strong everywhere. On 13 May the Tripolitans tried to storm the town, driving the Arab mercenaries back almost to the governor’s palace. Eaton directed the town’s guns and naval fire onto the Tripolitans as they advanced and this broke up their attack. There were several further attempts like this to retake the port, but each one was driven off. By the beginning of June, Eaton felt sufficiently confident to renew the offensive. He led a second desert march, hoping to close on Tripoli itself, but the signing of a peace treaty prevented this final, daring plan from being executed. The terms of the treaty were controversial, but Tripoli was forced to relinquish 300 American prisoners, for which they were paid $60,000. Tripoli remained cowed for two years, until a new round of piracy led to a Second Barbary War in 1815.

The epic struggle with the Barbary pirates was the first occasion on which the newly independent United States conducted operations on foreign soil in defence of its national interests. It was a war marked by acts of astonishing courage in the face of considerable odds. Lieutenant Decatur’s gallant raid on the Philadelphia was praised by Britain’s Horatio Nelson, the victor of the battles of the Nile and Trafalgar, as ‘the most bold and daring act of the age’. Somers’s equally courageous act was denied success but illustrated the remarkable spirit of the new American navy. Eaton and O’Bannon demonstrated incredible endurance and determination in their desert march to Derna, and, against the odds, they succeeded in seizing and holding a strategic port against far greater numbers of enemy forces. Rightly, the United States Navy and Marine Corps are proud of these pioneering achievements, which set such a high standard.