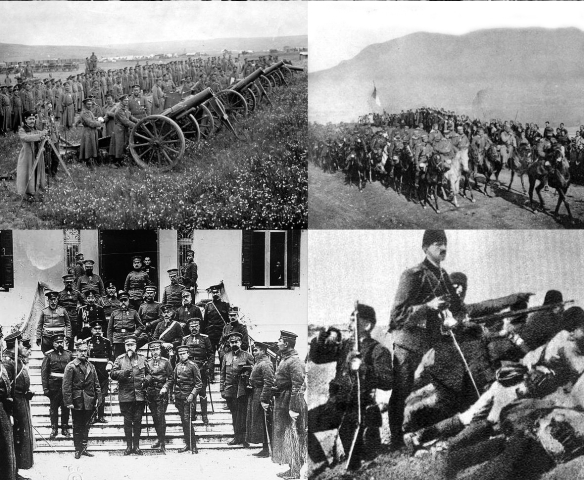

Clockwise from top right: Serbian forces entering the town of Mitrovica; Ottoman troops at the Battle of Kumanovo; the Greek king and the Bulgarian tsar in Thessaloniki; Bulgarian heavy artillery.

The two wars in the Balkans not only ended the Ottoman Empire’s foothold in Europe but created new states. It also brought to the surface many regional hostilities. This map shows the scope of the conflicts from the Adriatic to the Black Sea.

Turkish Forces on Left; Greek, Serbian, Bulgarian, and Montenegrin on Right

In 1911 Italy, who wanted to carve out its own empire in North Africa, declared war on the Ottoman Empire, which had been declining steadily for well over a century, in order to seize Turkish-held Libya. At the same time, former Turkish domains Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia, encouraged by Russia, formed the Balkan League with a view to wresting Montenegro from the Turks and forcing them out of Europe.

The Balkan League, in alliance with the small state of Montenegro, declared war on Turkey on October 8, 1912. Together the League and Montenegro could muster about 350,000 troops, while the Turks had fewer than 250,000 men available to them in Europe. Toward the end of October forces from each of the Balkan countries marched into Turkey’s European territories.

The Greeks under Crown Prince Constantine (1868-1923) advanced into Turkish-held Macedonia from the south and defeated an Ottoman force at Elasson on October 23. Despite the initial success, Constantine soon ran into trouble first at Venije Vardar and later at Kastoria and Banitsa. By November 5, however, the Greeks had overcome their adversaries and claimed an important victory at Venije. The Greek Army then pressed eastward to Salonika. Both the Greeks and the Bulgarians coveted this vital port, the possession of which would allow its owner domination of the Aegean.

Meanwhile, the Serbs, led by General Radomir Putnik (1847-1917) advanced into Macedonia from the north, defeated the Turks at Kumanovo on October 24, and forced them to retreat to Monastir. The Battle of Monastir, held on November 5, was a hard-fought contest with both Serbs and Turks showing great bravery. An impetuous Serb assault on a Turkish position was thrown back by the Turks with heavy Serb casualties. But this attack weakened the Turkish center, and allowed the Serbs to launch a frontal attack, which made inroads into the Turkish position. Threatened by a Greek force advancing from the south, the Turks retreated, having lost 20,000 men in the battle. The Greeks then captured the fortress of Salonika four days later and placed a number of other Turkish garrisons, including Scutari, under siege.

The Turks fared no better in Thrace, where they faced the Bulgarians. Three small Bulgarian armies advanced on a broad front and defeated the Turks at Seliolu and Kirk Kilissa at the end of October. The Turks fell back toward Constantinople (modern Istanbul) to hold a 35-mile (56-km) long defensive line between Lülé Burgas and Bunar Hisar. Two of the Bulgarian armies pressed eastward after the Turks, while the third placed the city of Adrianople under siege.

The Bulgarian attacks on the Turkish defensive line at Lülé Burgas on October 28-29 were successful and the Turks pulled back toward Constantinople. They took up a position along the Chatalja Line, their last defensive barrier before the Turkish capital. The Bulgarians tried to smash through the line during November, but all their efforts proved unsuccessful and Constantinople was safe from the Bulgarians. As a result of intervention by the major European powers, however, peace talks began in December and an armistice brought the war to a halt temporarily.

Peace negotiations collapsed, however, as a result of the incompatible demands of the various states. Turkey was required to surrender most of its European possessions, and a new state of Albania was to be created on the Adriatic, although this latter move was bitterly opposed by Serbia and Montenegro. But the chief cause of dispute lay in Bulgaria’s well-grounded fear that Greece and Serbia were conspiring to divide Macedonia among themselves at the expense of Bulgaria. The Balkan League might have been united in their determination to defeat the Turks, but their own regional ambitions would prove their undoing.

Complicating matters further, the Turkish government was overthrown in January 1913 and replaced by a fiercely nationalist group known as the “Young Turks,” led by Enver Bey (1881-1922). The new Turkish government was determined to carry on the war in the hope of gaining better peace terms for Turkey. Despite their best efforts, the Turkish armies suffered further defeats in 1913. The Turkish cities of Yannina (March 3), Adrianople (March 26), and Scutari (April 22) all fell to the Balkan League, forcing the Turks to sue for peace. The ensuing Treaty of London saw Turkey lose virtually all of its possessions in the Balkans.

The Second Balkan War

The Balkan League did not survive its victory in the First Balkan War. and national rivalries soon tore the alliance apart. Hoping to get a larger slice of Macedonia and. above all, the port of Salonika, Bulgaria attacked the Serbs on May 30, 1913, before declaring war on both Serbia and Greece. Bulgaria severely underestimated the strength of its former allies, and by June 30 its forces were halted by the Serbo-Greek coalition. On July 2 Serb forces under Putnik drove back the Bulgarians, and despite a failed counteroffensive, the Bulgarians were virtually defeated.

Then an already desperate situation faced by Bulgaria worsened when, on July 15, Romania sided with Serbia and Greece against Bulgaria. With great speed the Romanian troops advanced on the Bulgarian capital of Sofia. At the same time, taking advantage of Bulgaria’s troubles with Serbia, Greece, and Romania, the Turks recaptured Adrianople. The Bulgarians were quickly forced to the peace table and on August 10, 1913, the Treaty of Bucharest brought the war to a close. Bulgaria was forced to give up most of the land it had gained during the war against Turkey, as well as losing some of its northern territories to Romania. Greece, on the other hand, was given Crete and southern Macedonia, and Serbia gained Kosovo and northern Macedonia, although Austria forced them to relinquish their gains in the newly formed Albania.

The peace in the Balkans did not last long, however, and the region remained unsettled as the competing ambitions of the Balkan states were supplemented by the larger ambitions of the rival great powers, Russia and Austria-Hungary. Bulgaria remained resentful as a result of the losses it had incurred at the end of the Second Balkan War, while Turkey licked its wounds and with the help of Germany set about modernizing its armed forces. Within the space of a year, in Sarajevo, Bosnia, the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, by a Serb nationalist would throw the Balkans into chaos and spark the outbreak of World War I.