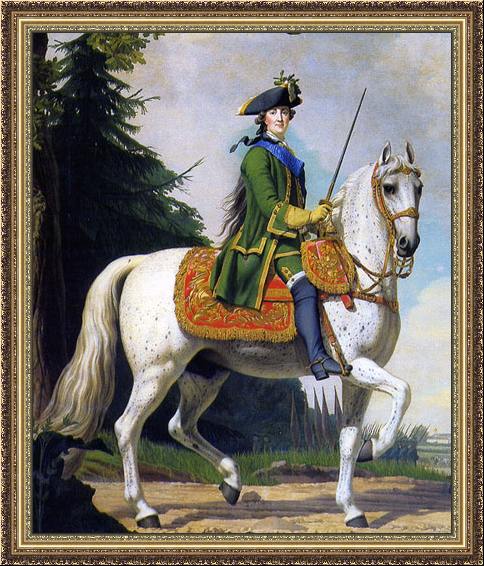

Equestrian portrait of Catherine in the uniform of the Preobrazhensky Regiment

Allegory of Catherine’s Victory over the Turks (1772), by Stefano Torelli.

The geography of eastern Europe – vast spaces, broad plains, large areas of forest, wide rivers, and (in the Balkans) mountainous terrain – meant that the style of warfare was often quite different from that in western Europe. A typical example of this was the importance of light cavalry, able to cover long distances quickly and frequently armed with firearms so that they could fight on foot if need be. Cavalry forces, such as Polish lancers or hussars, Cossacks from the steppes of southern Russia, or the spahis of the Ottomans, were often crucial during campaigns, whereas they played a more peripheral role in western Europe. Light infantry forces were also able to operate in wooded or mountainous terrain, and were far more important than in the west, where “line” infantry (that is, infantry trained to fight in a solid line) ruled the battlefield. And, given the relative sparsity of major fortified towns or cities, the sieges of such places often became crucial. Belgrade, for example, was the focus of warfare between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans throughout the century.

Catherine the Great concentrated on expanding the Russian Empire westward, specifically at the expense of two weaker powers: Poland and the Ottoman Empire.

While the successes of Europe’s powers around the world provided indicators of the strength of Europe’s military organization and technology, most Europeans were more impressed by victories closer to home – such as the defeat of the long-time enemy power of the Ottoman Empire. In 1683 Ottoman forces had laid siege to Vienna, but it was to be the last serious threat posed by them in the region.

The institutions of the Ottoman Empire had been becoming less effective – long wars against Persia in the 17th century had run down its resources, and the innovation which had characterized elite corps such as the Janissaries was steadily eroding. There was little appetite for reform from within and many provinces had become virtually independent, failing to contribute to the strength of the empire overall. So, after the relief of Vienna, the Hapsburgs led an offensive by armies of the Holy League (Polish and Venetian troops played a major part) to conquer Hungary. Then, from 1714 to 1718, Hapsburg forces under Prince Eugene enjoyed a series of successful campaigns against the Turks, consolidating in Hungary and taking Belgrade. In the 1730s, though, the Ottomans retook Belgrade and defeated Russian encroachments in the Crimea.

Having stalled the Hapsburgs, the Ottomans were to gain a new foe in Russia, which had developed into a major power under Peter the Great and then, under Empress Elizabeth, had played an important part in the Seven Years War. Six months after Elizabeth’s death, her daughter-in-law, Catherine, took power in a coup. Catherine set Russia on an expansionist course, using the resources of the vast state to create a large army.

Catherine the Great’s (as she became) first major military adventure was conducted against a group of rebellious Polish nobles known as the Confederation of the Bar. They opposed Russia’s growing involvement in Poland and objected to their own (pro-Russian) government. The rebellion, which began in 1768, was put down by the Russians, but the rebels had called on Turkey to aid them. The Turks had, in fact, ignored the calls for assistance, but Russian troops chased some of the rebels into Turkish territory and destroyed a town in the process, provoking Turkey to declare war. The Russian Army redeployed southward, defeating the Turks in the Caucasus and then invading the Balkans in 1769. The Russian commander. Count Peter Rumiantsev, smashed a Turkish army on the Dniester River, took the town of Jassy, and then conquered the Turkish-held provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia.

Russian Gains

The Russians then backed revolts in Turkish-controlled Egypt and Greece. These did not succeed, but the Russians were victorious elsewhere. At the naval Battle of Chesme, fought off the Mediterranean coast of Turkey on July 6, 1770, a Russian force led by Admiral Aleksei Orlov overwhelmed a Turkish fleet. And in August, Rumiantsev, taking advantage of his victory on the Dniester, defeated a Turkish force that had been mustered to eject him from Moldavia.

In 1771 Catherine’s forces continued to make further inroads into Turkish territory. Prince Vasily Dolgoruky advanced into the Crimea, conquering the peninsula. The Turks opened peace negotiations in 1772. However, this conciliatory move was simply a ploy to allow them to rebuild their forces. War broke out again in 1773, but the Turks only met with further disasters.

Rumiantsev advanced south from his position along the Danube River against the main Turkish field army, which fell back on Shulma. General Alexander Suvarov then tackled the Turks at Shulma in June 1774 and won a famous victory. Weariness began to set in and the Treaty of Kuchuk Kainarji was signed on July 16: Russia returned some of the territories it had captured but, significantly, gained access to the Black Sea, a stretch of water whose coastline had previously been the sole preserve of the Turks. The Ottoman Empire never recovered from this change in the balance of power.

The peace lasted for 14 years. The Russians intrigued with local tribes to gain control of Georgia, ruled by the Turks, while the latter encouraged the Crimean tribes to rebel against their new overlords. However, in 1788 Suvarov defeated the Turks at Kinburn, thereby preventing them from reconquering the Crimea. The Russians were also successful at sea. John Paul Jones, the naval hero of the American Revolutionary War, led the Russian fleet into action at the two Battles of Liman in June 1788.

The focus of the war switched to Moldavia in 1789. The Austrians invaded from the west, while the Russians advanced from the north. A united Russian and Austrian army was then resoundingly successful at the Battle of Foscani on August 1, forcing the Turks to fall back to the Danube River. With other attacks in the Balkans and the loss of Belgrade, the Turks became alarmed and sought to negotiate a treaty with Austria. The peace deal in 1791 let Turkey regain Belgrade but cede control of other parts of the Balkans.

The Turks had to deal with a revolt in Greece in 1790 that undermined their ability to focus on holding back the Russians. Then, on December 22, General Suvarov captured the important fortress of Ismail at the mouth of the Danube. When it fell, he ordered the massacre of all its Turkish defenders, after which he was promoted. Despite these victories, Russia was eager to reach a peace agreement with Ottoman Turkey. This was a consequence of renewed problems in Poland, where the Prussians were trying to increase their political influence. The Treaty of Jassy was signed on January 9, 1792: the Russians returned Moldavia and Bessarabia to the Turks but kept hold of the territories to the east of the Dniester. Thus, a century after the siege of Vienna in 1683, the Ottoman Empire was in retreat, grimly hanging on to its possessions in Europe against stronger powers. It was a significant change in the balance of power.

Catherine the Great also had the large but weakly ruled state of Poland in her sights. In 1772 she came to an agreement with Austria and Prussia by which they all occupied some Polish land. There was a further partition agreed between Russia and Prussia in 1792. In 1794 Polish nationalists, commanded by Thaddeus Kosciusko, began to rebel against the dismemberment of their country. Kosciusko’s poorly armed forces were soon forced back to Warsaw, which was besieged in late August. The heavily outnumbered Poles, some 35,000 soldiers with 200 guns, defended their capital with great valor, repulsing two major assaults by the Russo- Prussian armies, whose combined strength totalled 100,000 soldiers and 250 guns.

Incredibly, at the beginning of September, the siege was broken by the Poles. The victory was short-lived, however. On October 10 at the Battle of Maciejowice, Kosciusko, with just 7,000 men, was decisively defeated. He was wounded and captured and the rebellion quickly collapsed. Poland disappeared as an independent country in 1795.

Between 1788 and 1790 Catherine the Great had also fought a war against Sweden. Despite two early defeats, the Swedes recovered sufficiently to take on the Russian Navy in July 1790. The battle left the Russian fleet in tatters as 53 ships were sunk by the Swedes. Peace between the two countries followed, on August 15. 1790.

By 1790, Europe was a continent in which there was great expertise in the conduct of warfare, and whose technology and organization for war was superior to those of any other societies in the world. Over the period from 1792 to 1815, this expertise was to be heightened even further, as the conduct of war took a very new turn under one of the greatest commanders in history Napoleon Bonaparte.