The entry for the year 885 in the French Annals of St Vaast begins with the chilling phrase: “The rage of the Northmen was let loose upon the land”. It was an all too accurate assessment. As soon as the winter snows had melted, a frenetic series of Viking raids hit the French coast and continued with a ferocity not seen for half a century. This particular year was especially demoralizing because the Frankish population had believed that they had gained the upper hand against the raiders. Four years earlier, the Franks had met the Norse in a rare pitched battle and slaughtered some eight thousand of them. For several years the threat of attack had receded, but then in 885 the Norse launched a full-scale invasion.

Viking attacks were usually carried out with limited numbers. They were experts in hit and run tactics, and small bands ensured maximum flexibility. That November, however, to the horror of the island city, more than thirty thousand Viking warriors descended on Paris.

From the start, their organization was fluid. According to legend, a Parisian emissary sent to negotiate terms was unable to find anyone in charge. When he asked to see a chieftain he was told by the amused Norse that, ‘we are all chieftains’. There was a technical leader – traditionally he is known as Sigfred – but not one the Franks would have recognized as ‘King’. It was less of an army than a collection of war bands loosely united by a common desire for plunder.

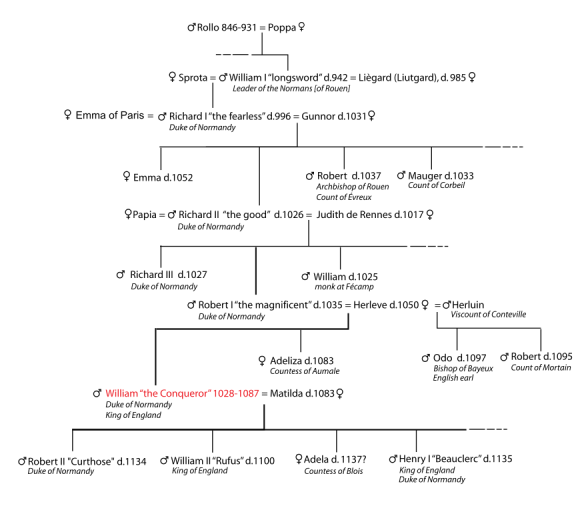

The Vikings launched an attack hoping to catch the French off guard, but several days of intense fighting failed to break through the Parisian defenses. The resulting siege, which lasted for a year, was ultimately unsuccessful, but it gave Europe its first glimpse of the man whose descendants would dominate both ends of the continent, and whose distant relative still sits on the English throne. Known to posterity as Rollo (the Latin version of the Norse Hrolf), he was a minor leader, probably of Norwegian extraction. According to legend he was of such enormous size that the poor Viking horses couldn’t accommodate him, and this earned him the nickname Rollo the Walker (Hrolf Granger), since he had to go everywhere on foot.

Like all the Vikings, Rollo had been drawn to the siege by the very real prospect of making a fortune. Forty years before, the legendary Norse warrior Ragnar Lodbrok had sacked Paris with fewer men, returning home with nearly six thousand pounds of silver and gold courtesy of the terrified French king. All of those present had undoubtedly been brought up on stories about Ragnar’s exploits, and there may even have been a veteran or two among the gathered warriors. This was their chance to duplicate his exploits.

If Rollo distinguished himself at Paris, it was in his determination. When it became apparent that an early victory wasn’t possible, many of the Norse began to drift away towards easier targets. By March of the next year, morale among the Vikings was so low that the nominal leader, Sigfred, reduced his demand to sixty pounds of silver – a far cry from Ragnar’s six thousand – to lift the siege. However, a rumor that the Frankish emperor, Charles the Fat, was on his way with a relief army stiffened the will of the Parisians and they refused. Sigfred held out another month, and then gave up, leaving Rollo and the other lesser leaders on their own.

The Frankish army finally arrived in October, eleven months after the siege began, and scattered what was left of the Vikings. Rollo’s men were surrounded to the north of Paris at Montmartre, but Charles the Fat decided to negotiate instead of attack. The province of Burgundy was currently in revolt, and Charles was hardly a successful military commander. In exchange for roughly six hundred pounds of silver, Rollo was sent off to plunder the emperor’s rebellious vassal.

It was an agreement that suited both of them, but for Rollo, the dream of Paris was too strong to resist. In the summer of 911 he returned and made a wild stab for it, hoping smaller numbers would prevail where the great army had failed. Not surprisingly, Paris proved too hard to take, so Rollo decided to try his luck with the more reasonable target of Chartres.

The Frankish army had been alerted to the danger and they marched out to meet the Vikings in open battle. A ferocious struggle ensued, but just when the Vikings were on the point of winning, the gates flew open and the Bishop of Chartres came roaring out, cross in one hand, relic in the other, and the entire population streaming out behind him. The sudden arrival turned the tide, and by nightfall Rollo was trapped on a hill to the north of the city. The exhausted Franks decided to finish the job the next morning and withdrew, but the crafty Viking was far from beaten. In the middle of the night he sent a few handpicked men into the middle of the Frankish camp and had them blast their war horns as if an attack were underway. The Franks woke up in a panic, some scrambling for their swords, the rest scattering in every direction. In the confusion the Vikings slipped away.

With the dawn, the Frankish courage returned, and they hurried to trap the Vikings before they could board their ships, but again Rollo was prepared. Slaughtering every cow and horse he could find, the Viking leader built a wall of their corpses. The stench of blood unnerved the horses of the arriving French, and they refused to advance. The two sides had reached an effective stalemate, and it was at this point that the French king, Charles the Simple, made Rollo an astonishing offer. In exchange for a commitment to convert to Christianity, and a promise to stop raiding Frankish territory, Charles offered to give Rollo the city of Rouen and its surrounding lands.

The proposal outraged Frankish opinion, but both sides had good reason to support it. The policy of trying to buy off the Vikings had virtually bankrupted the Frankish Empire. More than a hundred and twenty pounds of silver had disappeared into Viking pockets, an amount which was roughly one-third of the French coins in circulation. There was simply no more gold or silver to mint coins, and the population was growing resistant to handing over their valuables to royal tax collectors. Even worse for Charles, the Viking raids had seriously undermined his authority. It was impossible for the sluggish royal armies to respond to the Viking hit and run tactics, and increasingly his subjects put their trust in local lords who could offer immediate protection rather than some distant, unresponsive central government. The authority of the throne had collapsed, and now it was the feudal dukes who held real power. If Charles allowed another siege of Paris he would lose his throne as well. Here, however, was a solution that promised to make all the headaches go away. Who better to stop Viking attacks than the Vikings themselves? By gaining land they would be forced to stop other Vikings from plundering it. The nuisance of coastal defense would be Rollo’s problem, and Charles could focus on other things.

For his part, Rollo was also eager to accept the deal. Like most Vikings he had probably gone to sea around age fifteen and now, perhaps in his fifties, he was ready to settle down. Local resistance was becoming stronger, and there was little more to be gained in spoils. After decades of continuous raiding the coasts were virtually abandoned, and wandering further inland risked being cut off from the ships. This was an opportunity to reward his men with the valuable commodity of land and to become respectable in the process. Rollo jumped at the chance.

The Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, as it came to be known, created the Terra Normanorum – the land of the Northmen. This treaty of the Northman’s Duchy, or Normandy, was formally agreed to at a meeting between the two protagonists. The Viking warlord agreed to be baptized together with his entire army, and to perform the ceremonial act of homage to King Charles. Unfortunately, this last part was carried out with a certain lack of grace.

The traditional manner of recognizing a feudal lord was to kiss the royal foot, but Rollo wasn’t about to do any such thing. When Charles stuck out his foot, Rollo ordered one of his warriors to do the deed for him. The huge Norseman grabbed the king’s foot and yanked it up to his mouth, sending the hapless monarch sprawling onto his back. It was, had they only known, a fitting example of the future relationship of the Norman dukes to their French overlords.

Charles hoped that his grant of land was a temporary measure that could be reclaimed later. Such things had been done before and they never lasted beyond a generation. In Rollo, however, he had unwittingly found a brilliant adversary. Rollo instantly recognized what he had; a premier stretch of northern France with some of the finest farmland in the country. His genius – and that of his descendants – was a remarkable ability to adapt, and in the next decade he managed to pull off the extraordinary feat of transforming a footloose band of raiders into successful knights and landowners.

Rollo understood, in a way that most of those around him did not, that to survive in his new home he had to win the loyalty of his French subjects. That meant abandoning most of his Viking traditions, and blending in with the local population. He took the French name Robert, married a local woman, and encouraged his men to do the same. Within a generation the Scandinavian language had been replaced by French, and Norse names had virtually died out.

However, the Normans never quite forgot their Viking ancestry. St Olaf, the legendary Scandinavian king who became Norway’s patron saint, was baptized at Rouen, and as late as the eleventh century the Normans were still playing host to Viking war bands. But they were no longer the raiders of their past, and that change was most clearly visible in their army. Viking forces fought on foot, but the Normans rode into their battles mounted. Charges from their heavy cavalry would prove irresistible, and carry the Normans on a remarkable tide of conquest that stretched from the north of Britain to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

One final change took longer to sink in, but was no less profound. Christianity, with its glittering ceremonies and official pageantry, appealed to Rollo probably more out of a sense of opportunity than conviction. His contemporaries could have been forgiven for thinking that Odin had given way to Christ suspiciously easily. The last glimpse we get of Rollo is of a man hedging his bets for the afterlife. Before donating a hundred pounds of gold to the Church, he sacrificed a hundred prisoners to Odin.

Christianity may have sat lightly on that first generation of Normans, but it took deep root among Rollo’s descendants. There was something appealing to their Viking sensibilities about the Old Testament – even if the New Testament with its turning the other cheek wasn’t quite as attractive – and they took their faith seriously. When the call came to aid their oppressed brothers in the East, they would immediately respond; Norman soldiers provided much of the firepower of the First Crusade.

When Rollo finally died around 930, he left his son an impressive legacy. He had gone a long way towards turning his Viking followers into Normans, and turning an occupied territory into a legitimate state. For all that, however, troubling clouds loomed on the horizon. Normandy’s borders were ill-defined, and it was surrounded by predatory neighbors. Its powerful nobles had bowed to the will of Rollo while he was alive, but they saw little reason why they should extend the same loyalty to his son. Most worrisome of all was the French crown, which eyed Rouen warily and was always looking for an excuse to reclaim its lost territory.

Rollo had laid the foundation, but whether Normandy would prosper, or even survive at all, was up to his descendants.