In choosing Verdun as the main German objective for 1916, General Erich von Falkenhayn, Chief of the German General Staff and Minister for War, pre-dated the jibe that the British would fight to the last man in the armies of their allies. Falkenhayn reasoned that, for the British, the European fronts in the First World War represented nothing more than a sideshow, with the Russian, Italian and French armies as their whipping boys. The Italians and Russians, Falkenhayn believed, were already foundering on their own ineptitude. Only France remained.

“France has almost arrived at the end of her military effort.” Falkenhayn wrote to the German Kaiser Wilhelm II in December 1915.

If we succeeded in opening the eyes of her people to the fact that in a military sense they have nothing more to hope for . . . breaking point would be reached, and England’s best sword knocked out of her hand . . . Behind the French sector on the Western Front, there are objectives for the retention of which the French General Staff would be compelled to throw in every man they have. If they do so, the forces of France will bleed to death, as there can be no question of a voluntary withdrawal.

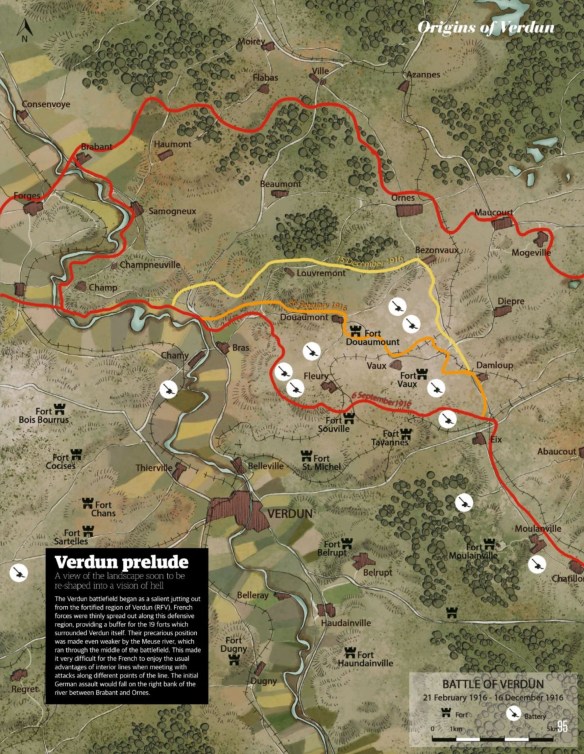

The objective Falkenhayn chose to put France in this moral and military dilemma was the massively fortified town of Verdun, on the canalized river Meuse. Verdun fitted Falken-hayn’s bill admirably. It had immense historic and emotional significance for the French and formed the northern linchpin of the double defense line of fortifications built to protect France’s eastern frontier after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1. Mount an assault here, with enough threatening potential, Falkenhayn reckoned, and the French Army would be inextricably lured to Verdun and mangled to extinction by the Germans. The mangle would be provided by a series of limited, but attritionist advances, intensively supported by artillery and spiced with surprise.

Falkenhayn’s proposals appealed to the Kaiser and to his son, Crown Prince Wilhelm, whose Fifth Army had been pounding away at Verdun with little success since 1914. But the prince and his Chief of Staff, General Schmidt von Knobelsdorf, seemed to see the Verdun campaign more in terms of shattering the French with a bombardment than of bleeding them dry by attrition. Wilhelm, who wanted to attack on both sides of the Meuse, not on the right bank only, as Falkenhayn proposed, stated the campaign’s purpose as “capturing the fortress of Verdun by precipitate methods”. Compared with this fierce phraseology, Falkenhayn’s notion of “an offensive in the Meuse area in the direction of Verdun” seemed enigmatic. Despite the suitably malevolent code-name of Operation Gericht (Judgement) given to his offensive, Falkenhayn’s essentially halfhearted approach to it planted the seeds of ultimate German failure at Verdun. Basically, that failure was rooted in Falkenhayn’s timid choice of too narrow a front for the initial attack and also in his extreme parsimony in doling out reserves.

Although Crown Prince Wilhelm and others seemed to suspect this outcome, preparations for the campaign went ahead as Falkenhayn had originally planned. It did so at a pace remarkable for those leisurely times. Weeks, rather than the usual months, divided Falkenhayn’s preliminary consultations with the Kaiser at Potsdam on or about 20 December 1915 from the issue of final orders on 27 January 1916 and the projected attack date of 12 February.

During this period, the Germans amassed in the forests that surrounded Verdun a massive force of 140,000 men and over 1,200 guns – 850 of them in the front line – together with 2.5 million shells brought by 1,300 munitions trains, and an air arm of 168 aircraft as well as observation balloons. A superlative standard of secrecy was achieved by deft camouflage of the guns, by the building of underground galleries to house the troops instead of the more usual, give-away “jump-off” trenches, and by dawn-to-dusk air patrols to prevent French pilots from casting spying eyes over the area.

These gargantuan preparations were, however, being directed against a military mammoth whose teeth had been drawn. By early 1916, Verdun’s much-vaunted impregnability had been seriously weakened. It had been “declassed” as a fortress the previous summer and all but a few of its guns and garrison had been removed. This was primarily the work of General Joseph J. C. Joffre, C-in-C of the French Army, who, with others, had presumed from the relatively easy fall in 1914 of the Belgian fortresses at Liège and Namur that this form of defense was redundant so far as modern warfare was concerned. Between August and October 1915, therefore, Verdun was denuded of over 50 complete batteries of guns and 128,000 rounds of ammunition. These were parcelled out to other Allied sectors where artillery was short. The stripping process was still going on at the end of January 1916, by which time the 60-odd Verdun forts possessed fewer than 300 guns with insufficient ammunition.

The result was that on the eve of the German offensive, the French defenses at Verdun were perilously weak, from the trench-works, dug-outs and machine-gun posts to the communications network and barbed-wire fences. Far-sighted men who protested at the headlong disarmament of Verdun did so in vain. One of them, General Coutanceau, was sacked as Governor of Verdun and replaced in the autumn of 1915 by the ageing and apparently more tractable General Herr. Another, Colonel Emile Driant, commander of 56th and 59th Chasseur Battalions of 72nd Division, 30th Corps, warned as early as 22 August 1915: “The sledge-hammer blow will be delivered on the line Verdun-Nancy.” After his opinion reached the ears of Joffre, Driant was sharply reprimanded in December for arousing baseless fears. Gen. Herr quickly realized that Coutanceau’s alarm had been perfectly justified, and that he was in dire need of reinforcements to prepare the defense line Joffre had ordered at Verdun. But Herr’s pleadings did little to penetrate the cloud of smugness that swirled about the question of defending Verdun. This mood remained impervious for some weeks, despite information from German deserters about troop movements and cancelled leave and other glimpses at the dire truth.

The very last moment had almost arrived before a glimmer of sense started to seep through. On 24 January General Nöel de Castelnau, Joffre’s Chief of Staff, ordered a rush completion of the first and second trench lines on the right bank of the Meuse, and a new line in between.

On 12 February, two new divisions arrived at Verdun – much to Herr’s heartfelt relief – to bring French strength up to 34 battalions against 72 German. Had the German attack begun on 12 February as planned, it would doubtless have smashed through the weak French defenses to score a stunning steamroller victory.

As it was, 12 February was not a day of savage battle, but of snow-blizzards and dense mist which afforded less than 1,100 yards visibility. The Verdun area was said to “enjoy” some of France’s filthiest weather. For a week it lived up to its reputation with snow, more snow, rain-squalls and gales.

Not until 21 February – just before 0715 – did a massive shell, almost as high as a man, burst from one of the two German 15-in (380 mm) naval guns and roar over the 20 miles that separated its camouflaged position from Verdun. There, it exploded in the courtyard of the Bishop’s Palace. At this signal, a murderous artillery bombardment erupted from the German lines and a tornado of fire – including poison gas shells – began to flay the French positions along a six-mile front. The earth convulsed and the air filled with flames, fumes and a holocaust of shrapnel and steel which, the Germans clearly hoped, would destroy every living thing within range. The bombardment hammered on and on until about 1200, when it paused so that German observers could see where – if anywhere – pockets of French defenders survived. Then the artillery began afresh, smashing trenches, shelters, barbed wire, trees and men until the whole area from Malancourt to Eparges had become a corpse-littered desert.

Between 1500 and 1600, the barrage intensified as a prelude to the first German infantry advance along a 4.5-mile front from Bois d’Haumont to Herbebois. The advance began at 1645 when small patrol groups came out over the 656 to 1,203 yards of No Man’s Land in waves 87.5 yards apart. Their purpose was to discover where French resistance might still exist and to pinpoint it to the artillery – which would then finish off the surviving defenders. This tentative approach, the result of Falkenhayn’s excessive caution, was not to the taste of the belligerent General von Zwehl, commander of 7 Reserve Corps of Westphalians. Von Zwehl, whose position lay opposite Bois d’Haumont, paid brief lip-service to Falkenhayn’s orders by sending out probing patrols first, but only a short while elapsed before he ordered his fighting stormtroopers to follow them. The Westphalians surged into the Bois d’Haumont, overran the first line of French trenches and within five hours had seized the whole wood.

To the right of the Bois d’Haumont lay the equally devastated Bois des Caures. Here, 80,000 shells had fallen within one 500,000-square-yard area. In this shattered wasteland, the advance patrols of the German 18 Corps expected to find nothing but mounds of shattered bodies in the mud. Instead, they were faced with a fierce challenge from Colonel Driant’s Chasseurs. Of the original 1,200 men under Driant’s command, fewer than half had survived the artillery bombardment. Now, these survivors poured machine-gun and rifle fire at the infiltrating Germans from the concrete redoubts and small strongholds which Driant had cunningly scattered through the trees.

Similarly ferocious isolated resistance was occurring all along the front, causing the Germans more delay and more casualties – 600 by midnight – than they had reckoned possible. By nightfall on 21 February, the only hole decisively punched in the French line was in the Bois d’Haumont, where Gen. Zwehl’s Westphalians were now solidly entrenched. Elsewhere, the Germans had captured most of the French forward trenches, but were held up when darkness put an end to the first day’s fighting which had yielded only 3,000 prisoners.

On the next two days, the Germans attacked with far greater force and much more initiative. On 22 February they blasted the village of Haumont, on the edge of the wood, with shellfire and flushed out the remaining French defenders with bombs and flamethrowers. That same day, the Bois de Ville was overwhelmed and in the Bois des Caures, which the Germans enveloped on both sides, Col. Driant ordered his Chasseurs to withdraw to Beaumont, about half a mile behind the wood. Only 118 Chasseurs managed to escape. Driant was not among them. On 23 February, the Germans saturated Samogneux with a hail of gunfire, captured Wavrille and Herbebois, and outflanked the village of Brabant, which the French evacuated. Next day – 24 February – despite their inch-by-inch resistance, the pace of disaster accelerated for the French with 10,000 taken prisoner, the final fall of their first defense line and the collapse of their second position in a matter of hours.

The Germans were now in possession of Beaumont, the Bois de Fosses, the Bois des Caurieres and part of the way along La Vauche ravine which led to Douaumont.

Incredibly enough, at first the magnitude of the disaster did not sink in at Joffre’s HQ at Chantilly, where the Staff had persuaded themselves that the German attack was a mere diversion. “Papa” Joffre, who had long believed a serious German offensive was more likely in the Oise valley, Rheims or Champagne, maintained his customary imperturbability to such an extent that at 2300 on 24 February, he was fast asleep when General de Castelnau came hammering on his bedroom door bearing bad news from the front. Armed with “full powers” from Joffre, who then went calmly back to bed, de Castelnau raced overnight to Verdun.

At about the time he arrived there, early on 25 February, a 10-man patrol of 24th Brandenburg Regiment of 3 Corps walked into Fort Douaumont and took possession of it and its three guns while the French garrison of 56 reserve artillerymen slept. This farcical episode, which German propaganda exaggerated into a hard-fought victory, shocked the French into melancholic despair and realization of the true state of affairs. At Chantilly, many officers openly advocated abandoning Verdun.

There, de Castelnau drew the conclusion that the French right flank should be drawn back and that the line of forts must be held at all costs. Above all, the French must retain the right bank of the Meuse, where de Castelnau felt that a decisive defense could, and must, be anchored on the ridges. The hapless Gen. Herr was replaced forthwith by 60-year-old General Henri Philippe Pétain. De Castelnau cannibalized Pétain’s Second Army with the Third Army to form for him a new Second Army.

Pétain took over responsibility for the defense of Verdun at 2400 on 25 February, after arriving that afternoon to find Herr’s HQ at Dugny, south of Verdun, in a chaos of panic and recrimination. Pétain, however, judged the situation to be far less hopeless than it seemed, even though the loss of Fort Douaumont and its unparalleled observation point was a serious blow. He decided that the surviving Verdun forts should be strongly re-garrisoned to form the principal bulwarks of a new defense. Pétain mapped out new lines of resistance on both banks of the Meuse and gave orders for a barrage position to be established through Avocourt, Fort de Marre, Verdun’s NE outskirts and Fort du Rozellier. The line Bras–Douaumont was divided into four sectors – she Woevre, Woevre–Douaumont, astride the Meuse, and the left bank of the Meuse. Each sector was entrusted to fresh troops of the 20th (“Iron”) Corps. Their main job was to delay the German advance with constant counterattacks.

Pétain saw to it that the four commands were supplied with fresh artillery as it arrived along the Bar-le-Duc road – which was soon rechristened “Sacred Way”. Three thousand Territorials labored unceasingly to keep its unmetalled surface in constant repair so that it could stand up to punishingly heavy use by convoys of lorries – 6,000 of them in a single day. Along La Voie Sacrée came badly needed reinforcements to replace the 25,000 men the French had lost by 26 February – five fresh Corps of them by 29 February. Already, Pétain was topping up his stock of artillery from the 388 field guns and 244 heavy guns that were at Verdun on 21 February towards the peak it reached a few weeks later of 1,100 field guns, 225 80–105 mm guns and 590 heavy guns. He also set the 59th Division to work building new defensive positions.

His injection of new strategy, new blood, new supplies and new hope into the Verdun defense soon began to disconcert the Germans. In any case, their impetus was gradually grinding down. On 29 February, their advance came to an exhausted halt after the last of their initial energy had been expended in three days of violent attacks against Douaumont, Hardaumont and Bois de la Caillette.

At that juncture, apart from their own mood of ‘grievous pessimism’, the most damaging factor for the Germans was the French artillery sited on the left bank of the Meuse. Here, more and more Germans came under fire the farther along the right bank they advanced. The solution was obvious, as Pétain had long feared and Crown Prince Wilhelm and Gen. von Knobelsdorf had long urged. On 6 March, after a blistering two-day artillery barrage, the German 6 Reserve and 10 Reserve Corps, partly pushed across the flooded Meuse and in a swirling snowstorm, attacked along the left bank. A parallel prong of this new onslaught was planned to strike along the right bank towards Fort Vaux, whose gunners had been savaging the German left flank.

Despite a plastering from French artillery in the Bois Bourrus, the Germans sped along the left bank and swept through the villages of Forges and Regneville – ending by nightfall in possession of Height 265 on the Côte de l’Oie. This ridge was of crucial importance, since it led through the adjacent Bois des Corbeaux towards the long mound known as Mort Homme. Mort Homme possessed double peaks and offered two advantages to the Germans. First it sheltered a particularly active battery of French field guns, and secondly, from its heights there stretched a magnificent all-round vista of the surrounding countryside. This gave whoever possessed it a prize observation point.

But Mort Homme soon lived up to its grisly name. After storming the Bois des Corbeaux on 7 March and losing it to a determined French counter-attack next day, the Germans prepared another attempt on Mort Homme on 9 March – this time from the direction of Béthincourt in the NW. They seized the Bois des Corbeaux a second time, but at such a crippling cost that they could not continue.

Results were depressingly similar on the right bank of the Meuse, where the German effort faded out beneath the walls of Fort Vaux. Difficulties of ammunition supply had made the attack there limp two days behind the left bank assault. With that, the parallel effect of the German offensive was ruined.

Inexorably, perhaps inevitably, the fighting around Verdun was acquiring that quality of slog and slaughter, and of lives thrown away for petty, short-lived gains that was so familiar a characteristic of fighting in the First World War.

Both Pétain and, in his own way, von Falkenhayn, were devotees of attrition by gunpower rather than manpower, but between March and May, the struggle at Verdun, like some Frankenstein’s monster renouncing its master, assumed a will of its own and reversed this preference. German casualties mounted from 81,607 at the end of March to 120,000 by the end of April, and the French from 89,000 to 133,000, as the two sides battered each other for possession of Mort Homme. By the end of May, when the Germans had at last taken this vital position, their losses had overtaken their enemy’s. On the right bank of the Meuse, in the same three months, the fighting swung to and fro over the “Deadly Quadrilateral” – an area south of Fort Douaumont – to the tune of maniacal, endless artillery barrages, never resolving itself decisively in favor of one side or the other.

The process greatly weakened both contestants. Mutinous behavior and defeatist gossip became more common in the French ranks and French officers tacitly condoned this mood. More and more Germans, many of them terrified, clumsy 18-year-old boys were becoming sickly from exhaustion, the din of the guns and the filth in which they were forced to live.

Ennervation and dismay affected the heads as well as the bodies of the two opposing war efforts. By 21 April, Crown Prince Wilhelm had made up his mind that the whole Verdun campaign was a bloody failure and ought to be terminated. “A decisive success at Verdun could only be assured at the price of heavy sacrifices, out of all proportion to the desired gains,” he wrote. These sentiments were echoed by Gen. Pétain, who was being nagged by Joffre to mount an aggressive counter-offensive. Pétain baulked at the increase in human sacrifice which that implied and clung to the principle of patient, stolid defense. Pétain was in a difficult position. Verdun had already become a national symbol of implacable resistance to the Germans, and Pétain himself a national idol. On the other hand, Verdun was threatening to gobble up the whole French Army and it certainly presented a serious drain on the manpower being reserved by Joffre for the coming Anglo-French offensive on the Somme.

For both sides at Verdun, these falterings at the top opened the way for men more ruthlessly determined to escalate the fighting onto even more brutal levels. On 19 April, Pétain was made Commander of Army Group Center, a position which placed him in remote rather than direct control of operations. His place as commander of Second Army was taken by General Robert Georges Nivelle, whose freebooter style of warfare had caught Joffre’s attention during his series of audacious, if expensive, attacks along the right bank of the Meuse. Nivelle took over on 1 May, and arrived at headquarters at Souilly with the brash announcement: “We have the formula!” He was also responsible for a quotation attributed sometimes to Pétain: “Ils ne passeront pas!”

Nivelle’s formula displayed itself in all its gory wastefulness on 22/23 May, when General Charles Mangin staged a flamboyant attack on Fort Douaumont. After a five-day bombardment, which barely chipped the fort’s defenses, Mangin’s troops streamed out of their jump-off trenches straight into a hurricane of deadly German gunfire. Within minutes, the French 129th Regiment had only 45 men left. One battalion had vanished. The remnants of the 129th charged the fort and set up a machine-gun post in one casemate against which the defending Germans flung themselves in a matching mood of suicidal madness. Out of 160 Jägers, Leibgrenadiers and men of the German 20th Regiment who attempted to overcome the French nest, only 50 returned to the fort alive. By the evening of 22 May, Fort Douaumont was in French hands, but the Germans staged violent counterattacks, capping their onslaught with eight massive doses of explosive lobbed from a minethrower 80 yards distant. One thousand French were taken prisoner, and only a pathetic scattering of their comrades managed to stagger away from the fort.

This bloody fiasco ripped a 500-yard gap in the French lines and greatly weakened their strength on the right bank of the Meuse. Together with the fact that German possession of Mort Homme largely nullified French firepower on the Bois Borrus ridge, the self-destructive strife at Fort Douaumont gave great encouragement to the so-called “May Cup” offensive which the Germans planned for early June.

The inspiration behind “May Cup” was Gen. von Knobelsdorf, who had temporarily eclipsed Crown Prince Wilhelm. As Nivelle’s new opposite number, von Knobelsdorf soon displayed an equally implacable resolve to overcome the enemy by brute force. “May Cup” comprised a powerful thrust on the right bank of the Meuse by five divisions on under half the 21 February attack frontage. Its purpose was to lift Verdun’s last veil – Fort Vaux, Thiaumont, the Fleury ridge and Fort Souville.

On 1 June, the Germans crossed the Vaux ravine and after a frenzied contest forced Major Sylvain Raynal – commander of Fort Vaux – to surrender on 7 June. By 8 June, Gen. Nivelle had mounted six unsuccessful relief attempts, at appalling cost. He was stopped from making a seventh attempt only when Pétain expressly forbade it. Elsewhere – totably round the Ouvrage de Thiaumont – the fighting brought both sides terrible losses. The French alone were losing 4,000 men per division in a single action. By 12 June, Nivelle’s fresh reserves amounted to only one brigade – not more than 2,000 men.

With the Germans now poised to take Fort Souville – the very last major fortress protecting Verdun – ultimate disaster seemed imminent for the French. Eleventh-hour salvation came in the form of two Allied offensives in other theaters of war. On 4 June, on the Eastern Front, the Russian General Alexei A. Brusilov threw 40 divisions at the Austrian line in Galicia, in a surprise attack that flattened its defenders. The Russians took 400,000 prisoners. To shore up his war effort, now threatened with total collapse, Field Marshal Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Austrian C-in-C, begged Falkenhayn to send in German reinforcements. Grudgingly, Falkenhayn detached three divisions from the Western Front. Meanwhile, the French had been doing some pleading on their own account. In May and June, Joffre, de Castelnau, Pétain and French Prime Minister Aristide Briant had all begged General Sir Douglas Haig, the British C-in-C, to advance the Somme offensive from its projected starting date of mid-August. Haig at last complied on 24 June, and that day the week-long preliminary bombardment began.

At this juncture, a German 30,000-man assault on Fort Souville, which had begun with phosgene – “Green Cross” – gas attacks on 22 June had already crumpled. Despite its horrifying effects on everything that lived and breathed, the novel phosgene barrage was neither intense nor prolonged enough to sufficiently paralyze the power of the French artillery. This shortfall, together with German failure to attack on a wide enough front, their recent loss of air superiority to the French, their shrinking store of manpower and the ravages thirst was wreaking in their lines, combined to scuttle the German push against Fort Souville on 22 June. July and August saw increasingly puny attempts by the Germans to snatch the prize that had come so tantalizingly close, but all ended in failure and exhaustion. German morale was at its lowest. On 3 September, the German offensive finally faded in a weak paroxysm of effort. Verdun proper came to an end.

For the Germans, this miserable curtain-fall on the drama of Verdun was assisted by the fact that after 24 June, the exigencies of the fighting elsewhere denied them new supplies of ammunition and, after 1 July, men.

All that remained was for the French to rearm, reinforce their troops and counter-attack to regain what they had lost. By 24 August 1917, after a brilliant series of campaigns masterminded by Pétain, Nivelle and Mangin, the only mark on the map to show the Germans had ever occupied anything in the area of Verdun denoted the village of Beaumont.

During this counter-offensive, the formerly maligned forts reinstated themselves as powerful weapons of defence. As the French recaptured them, they found how relatively little they had suffered from the massive artillery pounding they had received. This discovery made forts fashionable among French military strategists once more. It did so most notably, and later mortally for France, in the mind of André Maginot, Minister for War from November 1929 to January 1931 and in that time sponsor of the Maginot Line of fortifications.

Of course, fortress-like durability was given neither to the 66 French and 43.5 German divisions which fought at Verdun between February and June 1916, nor to the terrain they so bitterly disputed for so long. Both suffered permanent scars. The land around Verdun, raked over again and again by saturation shelling – over 12 million rounds from the French artillery alone – became a ravaged, infertile lunar-like wasteland. By 1917, the soil of Verdun was thickly sown with dead flesh and irrigated by spilled blood, having claimed more than 1.25 million casualties. Between February and December 1916, the French had lost 377,231 men and the Germans about 337,000 in a scything down of their ranks. In these circumstances, the Western Front ceased to be a sideshow for the British – of it had ever been so. They were forced to assume the star role in the Allied war effort which the French had formerly played. A repetition of Verdun was simply inconceivable.