Dam Busting Raids

Ruhr industry was dependent on hydroelectric power and water, supplied by several huge dams. The destruction of the largest of these would have a devastating effect on German armaments output. But no ordinary bomb was capable of the task. In the Weybridge offices of Vickers, a quiet genius called Barnes Wallis applied himself to the problem.

The solution he came up with was a large mine, which had to be placed with absolute precision against the inner face of the dams by flying at exactly 220 mph (354 km/h) and 60 ft (18 m), releasing the weapon to an accuracy of less than one fifth of a second. A special squadron was trained specifically for the task. To lead it, Wing Commander Guy Gibson was chosen, and his aircrews were hand-picked from the best that Bomber Command could offer. They were predominantly British, but included 26 Canadians, 12 Australians, two New Zealanders and a single American. It is less widely known that the ground crews and support tradesmen were also hand-picked. Thus was the birth of No. 617 Squadron at Scampton in March 1943.

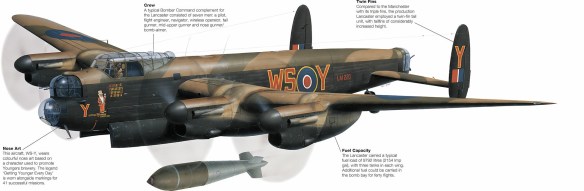

The mine, codenamed Upkeep, was a large cylindrical weapon weighing 9,250 lbs (4200 kg), over two-thirds of which was high explosive. Aircraft were taken from squadrons in No.5 Group. The bomb bay doors were removed and special brackets fitted, together with an electric motor to get Upkeep rotating at 500 revolutions per minute before release. The bomb bay was faired to front and rear of the mine in order to reduce drag and the mid-upper turret was removed. Transformed in this manner, the Mk Is became Type 464 Provisioning Lancasters.

Other changes were made as they were found necessary. The entire raid was to be flown at low level, so bomb aimers assisted navigation using a specially prepared roller map. The nose turret had to be manned continually, which gave a role to the otherwise redundant mid-upper gunner, and stirrups were fitted to prevent him treading on the bomb aimer’s head in moments of excitement.

Achieving the exact height over water at night proved difficult, but was solved by fitting Aldis lamps in the nose camera port and behind the bomb bay, angled so that the two spots of light touched at exactly 60 ft (18 m) and offset to starboard where they were easily seen by the navigator, who monitored height on the attack run.

Due to the low altitude required for the operation, standard bombsights could not be used. A simple device called the Dann sight was created in order to give the proper distance to target. It was made up from a plywood triangle, an eyepiece and a couple of nails or wooden dowels. The distance between two specific points on the dam was known, so the Dann sight was set up in such a fashion that when the nails or dowels lined up with these points, the correct distance was achieved for bomb release. Close control of the operation was vital, and for this Gibson had all Lancasters fitted with fighter-type VHF radios. This was the first use of the ‘Master Bomber’ technique, later to become standard throughout Bomber Command.

The Mohne Dam was known to be well defended, so it was assumed that the other targets were as well. Anticipating that the Lancasters would probably have to fight their way into and out of the target area, each gun was given three thousand rounds of tracer ammunition giving a total of 157 seconds firing time. By using all tracer ammunition it was hoped the Germans would overestimate the actual weight of fire and thus force them to keep their heads down.

Operation Chastise

The attack on the dams was set for the night of 16/17 May, when good weather was forecast the moon was full, and the water level behind the dams was at its highest. Nineteen Lancasters took off in three waves. The first wave consisted of nine aircraft in three Vics of three, led by Gibson. Its primary targets were the Mohne and Eder Dams. The second wave, of five Lancasters flying individually, took a more northerly route. Their target was the Sorpe Dam, of different construction to the first two and needing a different mode of attack, albeit with the same weapon. The third and final wave of five aircraft also flew individually. Taking off two hours after the others, it was a reserve to be used against the main targets if needed, otherwise to attack secondary dams in the area.

Opposition to the passage of the first wave was moderate, but Bill Astell’s Lancaster fell to light flak. The remainder arrived over the Mohne Dam on time. Gibson later wrote, ‘In that light it looked squat and heavy and unconquerable; it looked grey and solid in the moonlight, as though it were part of the countryside itself and just as immovable. A structure like a battleship was showering out flak all along its length’.

After circling to make an assessment of the situation, Gibson began his attack run, curving in down-moon, past the hills and low over the water. He had his spotlights on for height and the light flak saw him coming and opened up with everything they had. Bomb Aimer Spam Spafford released the mine and they swept low over the dam. From the air it looked like a perfect drop, but in fact the mine had fallen short.

Next came Hopgood, whose aircraft caught fire and crashed, while his mine bounced clear. Gibson then ordered Australian Mick Martin to attack. Martin’s Lancaster was hit, and its mine was released off course to detonate harmlessly. Dinghy Young made a perfect run and deposited his Upkeep right against the dam wall. Even as Malt by made his run, the parapet crumbled and the dam burst. His mine added to the breach made by Young.

Eder Dam

Martin and Maltby headed for home, while Gibson and Young led the three remaining armed Lancasters to the Eder Dam. Australian David Shannon made three attempts without being able to line up correctly. Henry Maudslay then tried twice, with no luck. On Shannon’s fourth attempt his mine exploded against the dam, causing a small breach. Maudslay tried once more, but his mine hit the parapet with him just above it. It was assumed that he and his crew died in the explosion, but badly damaged, he had limped some 130 miles (210 km) towards home before falling to flak.

Only one armed Lancaster remained, and on the second attempt its pilot, Les Knight, made a perfect run. His mine punched a hole clean through the giant dam wall. The fIrst aircraft to be lost during Operation Chastise was that of Eyers. Les Munro’s Lancaster was damaged by flak had to abandon the mission, while Geoff Rice, flying as low as possible, hit the sea and lost his mine. He also was forced to return. Barlow, an Australian, was claimed by flak just inside the German border, and of the ill-fated second wave, only the American, Joe McCarthy, survived. After making nine runs against the Sorpe he dropped his mine on the tenth, but without any visible results.

The final wave fared only slightly better. Burpee, a young Canadian from Gibson’s previous squadron, went down over Holland, while Ottley lasted only a little longer. Both fell to light flak. Of the other three, Anderson was the least lucky. Last off, the fates conspired to force him to abandon the mission without attacking.

Brown attacked the Sorpe after several attempts, like McCarthy with no visible result, while Townsend, on course for the Mohne Dam, was diverted to the Ennerpe Dam instead. After several brushes with flak, he emerged into an area made unrecognisable by floods from the already breached Mohne and Eder. Finally Townsend arrived at what appeared to be the Ennerpe and dropped his mine, but post-war evidence seems to indicate that he attacked the Bever Dam 5 miles (8 km) away.

The entire German air defence system was by now alert to the events. Apart from Maudslay, the only other loss was Dinghy Young. Hit by flak as he re-crossed the coast, be went down into the sea. Others, including McCarthy, Brown and Townsend, had eventful return flights, but recovered safely to Scampton.

Success had been expensive. Eight Lancasters failed to return home; of the 56 men on board, only three survived. Guy Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest decoration, and 33 other awards were made to participants in the raid. The Dams Raid has long passed into legend. No.617 Squadron had established itself as an elite unit.

A new role was sought for No. 617 Squadron. The modified Lancasters were replaced by standard Mk IIIs, and the crews started intensive high and low level training. Wing Commander Guy Gibson was replaced by Squadron Leader George Holden. On 30 August 1943, the squadron was ordered to Coningsby for low-level attacks.

Dortmund-Ems

The next target was the well defended Dortmund-Ems canal, a strategic artery in the German transport system. No. 617 squadron was to try, using the new 12,000 lbs (5440 kg) high-capacity bomb. Low cloud in the target area caused the first attempt to be recalled, minus Maltby, who went into the sea after hitting someone’s slipstream at low level. The next night they tried again. It was a disaster. Heavy mist in the target area foiled all attempts to bomb accurately, while the defences claimed five Lancasters, among them those of Holden and Les Knight. The squadron rapidly gained the reputation of being a suicide outfit. Six aircraft, with six more from No.619 Squadron, went out again the next night to attack the Antheor Viaduct in southern France at low level. This was another failure and the squadron was withdrawn from operations while changes took place.

One was the introduction of the Stabilizing Automatic Bomb Sight (SABS), introduced by Arthur ‘Talking Bomb’ Richardson, whom we last saw over Gdynia with Guy Gibson. No. 617 Squadron was now to become a medium and high-level ‘sniper’ squadron. The other was the arrival of Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire to command the unit on 11 November.

Cheshire was introspective and unconventional, and arguably the most inspirational bomber leader of the war. Always leading from the front, he was described by David Shannon as a pied piper; people followed him gladly. He set out to make the squadron live, breathe and eat bombing accuracy.

Several missions followed against pin point targets, but they were not a great success. Oboe marking was too inaccurate against small targets. Cheshire and Martin worked out between them that only low-level marking in a dive would be good enough, and on 3/4 January 1944, they tried it against a flying bomb site at Freval. By the illumination of flares, they marked from 400 ft (120 m), and 12,000 lbs (5440 kg) bombs from the remainder of the formation as they obliterated the target.

A more exacting test came on 8/9 February, by which time No.617 has moved to Woodhall Spa. The aero engine works at Limoges were almost totally destroyed, while damage to French houses close by was minimal. Other raids followed with equal success, the only failure during this time being another attempt against the Antheor Viaduct.

To mark heavily defended targets, smaller and faster aircraft were needed. The obvious choice was the De Havilland Mosquito, which Cheshire duly acquired, bringing the low-level marking career of the Lancaster to an end. At the same time, No. 617 became pathfinders and Main Force leaders to No.5 Group.

D-Day Deception

The first of these was Operation Taxable, a deception ploy that was designed to make the Germans think that a vast invasion fleet was moving towards Cap d’ Antifer, some 20 miles (30km) north of Le Havre. This was done by 16 Lancasters, flying precise speeds and courses, dropping Window at five-second intervals. Packed with Window bundles, they maintained the deception for some eight hours until dawn broke to reveal only an empty sea to the expectant Germans.

The second was the introduction of the Tallboy, a new 12,000 lbs (5440 kg) bomb with exceptionally good ballistic qualities and penetrative power. Like Upkeep, Tallboy was the idea of Dr Barnes Wallis, and only the SABS equipped Dam Busters could bomb accurately enough to make the best use of this new and devastating weapon.

One of the few south-to-north rail routes still open in France at this time passed through a tunnel near Saumur, on the Loire. Shortly after midnight on 8/9 June the squadron arrived, and Cheshire placed two red spot fires in the mouth of the tunnel. Nineteen Tallboy armed Lancasters moved in, plus another six with conventional loads. The result was a series of enormous craters that tore the line to pieces. One Tallboy had impacted the hillside and bored its way down to explode inside the tunnel almost 60 ft (18 m) below, completely blocking it.

More precision raids followed such as the raids on the concrete E-boat pens at La-Harve and V-weapon sites scattered around Pas-de-Calais and elsewhere. In July, command of the squadron passed from Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire to Wing Commander Willie Tait DSO DFC.

The Tirpitz

The German battleship Tirpitz lying in Alten Fjord in Norway, tied down British naval units which would have been better deployed elsewhere. Even from the most northerly of British airfields Alten Fjord was outside Lancaster range. A deal was struck with the Russians, who made Yagodnik, near Arkhangelsk, available as a refuelling stop. For this and subsequent anti-Tirpitz operations, No.617 was joined by No.9 Squadron, which, although fitted with the Mk XIV vector bombsight, was also something of an elite outfit. Of the 36 Lancasters detailed, 24 carried Tallboys; the others were loaded with 12 Johnny Walker Diving Mines each, an original but ineffective weapon.

The raid nearly ended in disaster when bad weather over Russia forced many Lancasters to land where they could. Six were abandoned in the marshes. On 15 September the attack was finally mounted, and the German early warning system proved equal to the task and a smokescreen quickly obscured the battleship. A single Tallboy hit was scored, but Tirpitz was still afloat. The Kriegsmarine moved her south to Tromso Fjord for use as a floating German gun battery; she would never sail again, but this was not known either.

Calculations showed that fitting internal fuel tanks in the fuselage of the Lancasters would allow Tirpitz to be attacked from Lossiemouth. On 20 October, 40 aircraft of Nos. 617 and 9 Squadrons set out on the long haul to Tromso. A combination of poor weather and enemy fighters made this attack a failure, and few crews even so much as saw the battleship.