No one would dispute the statement that the Avro 683 Lancaster was the finest British heavy bomber of World War II. A few would even argue that it was the finest heavy bomber serving on any side during the conflict, and it is therefore strange to recall that it had its genesis in the unsuccessful twin-engined Avro 679 Manchester.

However, it is not entirely true to say that the Lancaster was virtually a four-engined Manchester; a four-engined installation in the basic airframe had been proposed before Manchester deliveries to the RAF began. But the prototype Lancaster was, in fact, a converted Manchester airframe with an enlarged wing centre section and four 1,145 hp (854 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin Xs. This prototype initially retained the Manchester’s triple tail assembly but was later modified to the twin fin and rudder assembly which became standard on production Lancasters.

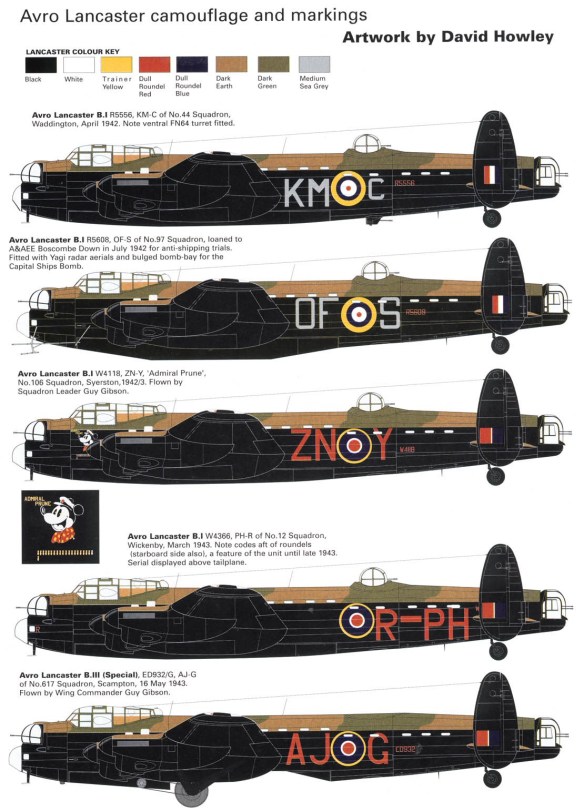

The BT308 prototype flew on 9 January 1941 and later that month went to the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment, Boscombe Down, to begin intensive flying trials. The second prototype DG595, with some modifications and Merlin XX engines rated at 1,280 hp (955 kW) for take-off , flew on 13 May 1941. In September of the same year the first prototype and several Manchester pilots were transferred to No.44 (Rhodesia) Squadron at Waddington for crew training and evaluation. The first three production aircraft were not delivered to the unit until Christmas Eve with another four aircraft arriving on December 28. No. 97 Squadron was the next unit to get the Lancaster in January 1942 followed by No. 207 Squadron in March 1942. The new bomber was an immediate success, and large production orders were placed. Such was the speed of development in wartime that the first production Lancaster was flown in October 1941, a number of partially completed Manchester airframes being converted on the line to emerge as Lancaster Is (from 1942 redesignated Lancaster B.Mk Is).

Avro’s first contract was for 1,070 Lancasters, but others soon followed, and when it became obvious that the parent company’s Chadderton and Yeadon production facilities would be unable to cope with the demand, other companies took on the task of building complete aircraft. They included Armstrong Whitworth at Coventry, Austin Motors at Birmingham, Metropolitan Vickers at Manchester and Vickers Armstrong at Chester and Castle Bromwich. Additionally, a large number of sub-contractors were involved in various parts of the country.

Lancasters soon began to replace Manchesters, and such was the impetus of production that a shortage of Merlin engines was threatened. This was countered by licence-production by Packard in the USA of the Merlin engine not only for Lancasters but also for other types.

An additional insurance was effected in another way, by the use of Bristol Hercules VI or XVI 14-cylinder sleeve-valve radial engines driving Rotal airscrews which in contrast to the Merlin airscrews, rotated counter-clockwise. Both engines were rated at 1,615 hp (1205 kW) for take-off. In this form, known as the Lancaster B.Mk II, prototype BT310 was flown on 26 November 1941 and results were sufficiently encouraging to warrant this version going into production by Armstrong Whitworth at Coventry. Delays were caused by the Ministry of Aircraft Production’s insistence on maintaining construction of Whitley bombers, but in May 1942 the changeover to Lancaster B.II production began, only to be halted for four months as a result of air-raid damage.

The first two Hercules-powered Lancasters were completed in September 1942 and went to the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment, where they were later joined by the third. Other Mk lIs from this first production batch were delivered to No. 61 Squadron at Syerston, Nottingham, the service trials unit for this version and a former Lancaster B.Mk I squadron. Early use of the Lancaster B.Mk II by No. 61 Squadron was plagued with minor problems, but during its six months of operations the squadron did not lose a single B.Mk II aircraft and in February 1943 was able to hand over the full complement of nine aircraft to No. 115 Squadron at East Wretham, a Wellington unit in No.3 Group.

Gradually Lancaster B.Mk IIs began to re-equip other squadrons, but the B.Mk II was never to achieve the success of the Merlin-engined Lancasters. It could not attain so high an altitude, was slightly slower, and had a bomb load 4,000 lbs (1814 kg) less than the other marks. Production ceased after 301 had been built, and the Armstrong Whitworth factory changed over to Lancaster B.Mk ls. It has been said that the phasing out of the Lancaster B.Mk II was in order to effect standardization, for the Handley Page Halifax B.III with Hercules engines was able to offer equal if not better possibilities, and with Lancaster B.Mk Is, Short Stirling’s and Halifax’s all in service, variations in spares requirements needed to be cut as much as possible.

The final Lancaster B.Mk II operation was flown by No. 514 Squadron on 23 September 1944, but a few continued in service for a short while into the postwar era, mainly as test-beds, until the last survivor was scrapped in 1950. Although overshadowed by its Merlin-engined contemporaries, the Lancaster B.Mk II did not disgrace itself and achieved on average more than 150 flying hours per aircraft.

Meanwhile, the Merlin Lancasters were going from strength to strength. The prototype’s engines gave way to 1,280 hp (954 kW) Merlin XXs and XXlIs, or 1,620 hp (1209 kW) for take-off Merlin XXIVs in production aircraft. Early thoughts of fitting a ventral turret were soon discarded, and the Lancaster B.Mk I had three Frazer-Nash hydraulically operated turrets with eight 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine-guns: two each in the nose and mid-upper dorsal positions and four in the tail turret. The bomb-bay, designed originally to carry 4,000 lbs (1814 kg) of bombs, was enlarged progressively to carry bigger and bigger bombs: up to 8,000 and 12,000 lbs (3629 and 5443 kg) and eventually to the enormous 22,000 lbs (9979 kg) ‘Grand Slam’, the heaviest bomb carried by any aircraft in World War II.

Production of the Lancaster was a comparatively simple affair considering its size. It had been designed for ease of construction and this undoubtedly contributed to the high rate of production. Lancasters were built to the total of 7,377 all marks. As mentioned earlier, No. 44 Squadron was the first to receive a Lancaster when the prototype arrived for trials and this squadron was also the first to be fully equipped with Lancasters, notching up another ‘first’ when it used the type operationally on 3 March 1942 to lay mines in “Operation Gardening” against Heligoland Bight on the German coast.

The Lancaster’s existence was not revealed to the public until 17 April of that year, when 12 aircraft from Nos. 44 and 97 Squadrons carried out an unescorted daylight raid on Augsburg, near Munich. Flown at low level, the raid inflicted considerable damage on the MAN factory producing U-boat diesel engines, but the cost was high, seven aircraft being lost. Squadron Leaders Nettleton and Sherwood each received the Victoria Cross, the latter posthumously, for leading the operation which perhaps confirmed to the Air Staff that unescorted daylight raids by heavy bombers were not a practicable proposition and it was to be more than two years before the US Army Air Force was to resume such attacks.

As Packard-built Merlins became available, so the Lancaster B.Mk III appeared with these engines, although the B.Mk I remained in production alongside the Packard-engined B.Mk III. Externally the B.Mk III was distinguishable by an enlarged bomb aimer’s ‘bubble’ in the nose but there were few other differences other than in minor equipment changes.

To swell the UK production lines, Victory Aircraft in Canada was chosen in 1942 to build Lancasters, and these were known as B.Mk Xs. Powered by Packard-built Merlins, the Canadian Lancasters were delivered by air across the Atlantic and had their armament fitted on arrival in the UK. The first B.Mk X was handed over on 6 August 1943, and 430 were built before production was completed.

Mention must be made of the Lancaster B.Mk VI, production of which was proposed using Merlin 85 or 87 engines, of 1,635 hp (1219 kW). Nine airframes were converted by Rolls Royce for comparative tests. No. 635 Squadron used several operationally on pathfinder work with nose and dorsal turrets removed. and fitted with improved H2S radar bombing aid and early electronic countermeasure equipment, but although performance was superior to the earlier marks no production aircraft were built.

It would be true to say that development of the Lancaster went hand-in-hand with development of bombs. The early Lancasters carried their bomb loads in normal flush-fitting bomb bays, but as bombs got larger it became necessary, in order to be able to close the bomb doors, to make the bays deeper so that they protruded slightly below the fuselage line. Eventually, with other developments, the bomb doors were omitted altogether for certain specialist types of bomb.

In this connection the most drastic changes suffered by the Lancaster were made to enable Dr Barnes Wallis’s ‘bouncing bombs’ to be carried to the Ruhr by No. 617 Squadron in its attacks on the Mohne, Ederand Sorpe dams, probably the best known raid made by either side in the European theatre during World War II. For this operation, the Lancaster B.Mk IIIs had their bomb doors and front turrets removed and spotlights fitted beneath the wings arranged in such a way that the beams merged at exactly 60 feet (18.3 m) below the aircraft, the altitude from which the bombs had to be dropped if they were to be effective. Nineteen Lancasters took part in the attack on the night of 17 May 1943, the attackers breaching the Mohne and Eder dams for the loss of eight aircraft.

The German battleship Tirpitz was attacked on several occasions by Lancasters until, on 12 November 1944, a combined force from Nos. 9 and 617 Squadrons found the battleship in Tromso Fjord, Norway, and sank her with the 12,000 lbs (5443 kg) ‘Tallboy’ bombs, also designed by Barnes Wallis. The ultimate in conventional high explosive bombs was reached with the 22,000 lbs (9979 kg) ‘Grand Slam’, a weapon designed to penetrate concrete and explode some distance beneath the surface, so creating an earthquake effect. No. 617 Squadron first used the ‘Grand Slam’ operationally against the Bielefeld Viaduct on 14 March 1945, causing considerable destruction amongst its spans.

Final production version of the Lancaster was the B.Mk VII, which had an American Martin dorsal turret with two 0.50 in (12.7 mm) machine-guns in place of the normal Frazer-Nash turret. The new turret was also located further forward.

In spite of the other variants built from time to time, the Lancaster B.Mk I (B.Mk 1 from 1945) remained in production throughout the war, and the last was delivered by Armstrong Whitworth on 2 February 1946. Production had encompassed two Mk I prototypes, 3,425 Mk Is, 301 Mk lIs, 3,039 Mk Ills, 180 Mk VIIs and 430 Mk Xs, a total of 7,377 aircraft. These were built by Avro (3,673), Armstrong Whitworth (1,329), Austin Motors (330), Metropolitan Vickers (1,080), Vickers Armstrong (535) and Victory Aircraft (430). Some conversions between different mark numbers took place.

Statistics show that at least 59 Bomber Command squadrons operated Lancasters, which flew more than 156,000 sorties and dropped, in addition to 608,612 tons (618380 tonnes) of high explosive bombs, more than 51 million incendiaries. As the war in Europe was drawing to its close, plans were being made to modify Lancasters for operation in the Far East as part of Bomber Command’s contribution to ‘Tiger Force’, but Japan surrendered before this could take place. A number of Lancasters were used to bring home prisoners of war from Europe, and various aircraft were modified for test flying in the UK and other European countries. Some were supplied to the French navy and others were converted for temporary use as civil transports, with faired in nose and tail areas, under the name Lancastrian. The Avro York transport used Lancaster wings and engines, plus a central fin in addition to the twin endplate fins.

A few Lancasters still survive, notably one airworthy example with the RAF Battle of Britain Memorial Flight and another used by the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in Canada.