“Askari” was a term applied to local Africans who served in European colonial forces. The entomology of the word comes from the Arabic word soldier and, as it was most commonly used in the eastern African context, reflects the mixed Swahili culture of the region. The term also means someone who is “locally recruited,” which carries special import in terms of Africans recruited from the colonies to serve European interests. The importance of the askari to the colonial project underscores the true nature of imperialism. Despite the claims of imperialists that European success was due to their cultural, racial, or technological superiority, the reality of most colonial conquest underscores European dependence on Africans to accomplish the aims of imperialism. For example, the famous colonial standoff at Fashoda, in that the French force consisted of seven Frenchmen and around 140 Senegalese, illustrates this reliance. African askari were of critical importance to nearly all of the colonial powers, although the manner in which they were organized and employed was as varied as the colonizers themselves.

What was common to the colonizers, at least initially, was a firm belief in a hierarchy of “martial races” that meant Africans from certain communities were seen as naturally good soldiers for the Europeans. Not only were these races deemed strong and hearty (useful qualities in any soldier), but also they were considered most willing to obey European officers. Often, this led to common recruitment practices as Europeans attempted to maximize their use of these martial races. Prized for their effectiveness against the forces of the Egyptian Khedive, and later against Europeans under the Mahdi, were Sudanese troops. Sudanese were recruited by both the British and the Germans, for example, to staff their initial forces. Even after such common recruiting practices went away, largely due to the solidification of colonial divisions, this belief in racial or ethnic hierarchy was sim- ply transferred to the specific colony or colonial holdings of the respective powers. Beyond racial categorization, askari often would be recruited on ethnic lines to ensure the connection of one people, group, or region to the colonizers. The very nature of recruitment was designed to divide and conquer the colony.

African soldiers were often utilized in regions not connected to their ethnic background to ensure that there would be no chance of common cause between colonial troops and African civilians. These tactics underscore that the role of the askari was as much about internal security as about de- fending the colony from foreign threats. Beyond such racial and political justifications were the practical matter that utilizing African troops made colonial conquest and administration far less costly in money and European lives. Every askari in a colonial force lowered the monetary cost of administration, as well as the risk to European troops, who often suffered mightily from the African climate and African diseases.

As Belgium’s King Leopold II served as one of the major catalyzing agents for the Scramble for Africa, it is unsurprising that his Force Publique (FP) employed askari. Leopold’s force reflected the views of the “martial race,” with his force initially recruiting heavily from the Sudan. Of the initial 2,000 askari, for example, only 111 were Congolese. Only in the 1890s were local chiefs required to produce recruits for ser vice to fill out the ranks. During the period of personal rule, the line between soldier and mercenary was thin, with the askari more readily employed as overseers to punish those African civilians who did not meet their rubber quotas. Famously, the Belgians went out of their way to recruit cannibals in order to heighten the potential terror of their troops. The largest action of the FP was during the Congo- Arab War, to repress Arab population centers along the Lualaba River. The war involved a massive number of African troops as the FP absorbed mercenaries and irregulars into their forces to quell the Arab states. After a three- year war, the Belgians were able to defeat the remaining Arab positions and solidify their control over the Free State. After the Belgian government acquired the colony, the askari became a more regularized force, both in weaponry and organization, which enabled the FP to acquit themselves in Africa during World War I.

In the British case, the use of Africans to fight for British interests was originally an ad-hoc affair. Frederick Lugard helped create the Central African Rifles and Uganda Rifles when serving the interests of British companies attempting to solidify their hold over the African interior. Eventually these ad- hoc units, as well as the East African Rifles, combined to form the King’s African Rifles (KAR) in 1902. The KAR served with distinction in colonial campaigns in Somalia and the German East Africa campaign of World War I. Lugard was also responsible for the creation of the askari forces in the British possessions in West Africa. He was the founding commander of the West African Frontier Force (WAFF), which was an amalgamation of a number of ad- hoc units in West Africa. This force was organized in order to protect Nigeria’s hinterland from French encroachment. Lugard utilized the force, however, to conquer the Sokoto caliphate in what is now northern Nigeria. The WAFF fought in World War I in Africa and was renamed the Royal West African Frontier Force (RWAFF) in 1928.

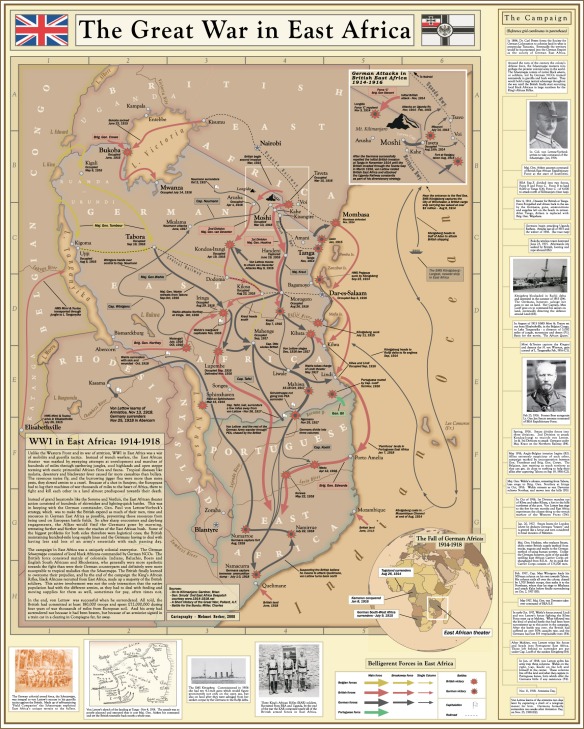

Despite the common utilization of the term askari, it is most readily associated with the German Schutztruppe (Protective Force) of the respective German colonies. Like other colonial forces, these units were created out of necessity to meet the needs of the imperial venture. In 1888, after suffering under the exploitive rule of Carl Peters and his German East Africa Company, Africans led an uprising against the company that took over nearly the entire coast. The German government, in responding to this threat against their interests, sent a force under the command of Hermann von Wissmann to repress the revolt. Originally, this Wissmann-Truppe consisted of a polyglot assembly of Africans (600 Sudanese, 100 Zulu from Mozambique, 80 East Africans, and 40 Somali), in line with the common European attitude of the martial races. The Sudanese were deemed the bravest soldiers with some Germans referring to them as “black lansquenets” in homage to the Germanic mercenary soldiers. This force, which was used to crush the rebel- lion, was then made the official protective force of East Africa by the German government. While initially relying on foreign Africans, the Schutztruppe shifted to utilizing locally recruited Africans (in other words, askari), primarily from the Nyamwezi people located in western Tanganyika. This region, heavily connected to the caravan culture of east Africa which required the service of young men as soldiers and porters, served as an attractive area of recruitment. While the forces in East Africa have attracted the most historic attention, largely due to their success in World War I, another primarily African Schutztruppe force was formed in German Cameroon, while an entirely white cavalry force was created in German South West Africa. These forces served as the punitive and protective force in the German colonies and then became the main fount of German resistance during World War I. Under Paul von Lettow-Vorbek, the east African Schutztruppe proved a thorn in the side of the British, as the Germans were able to conduct a guerilla campaign that tied down British imperial troops throughout the entire war.

Further Reading Jonas, Raymond. The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2011. Moyd, Michelle R. Violent Intermediaries: African Soldiers, Conquest, and Everyday Colonialism in German East Africa. Athens: Ohio University, 2014. Page, Malcolm. A History of the King’s African Rifles. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2011. Parsons, Timothy. The African rank and file: Social implications of colonial military ser- vice in the King’s African Rifles, 1902-1964. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1999. Vandervort, Bruce. Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa 1830-1914. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.