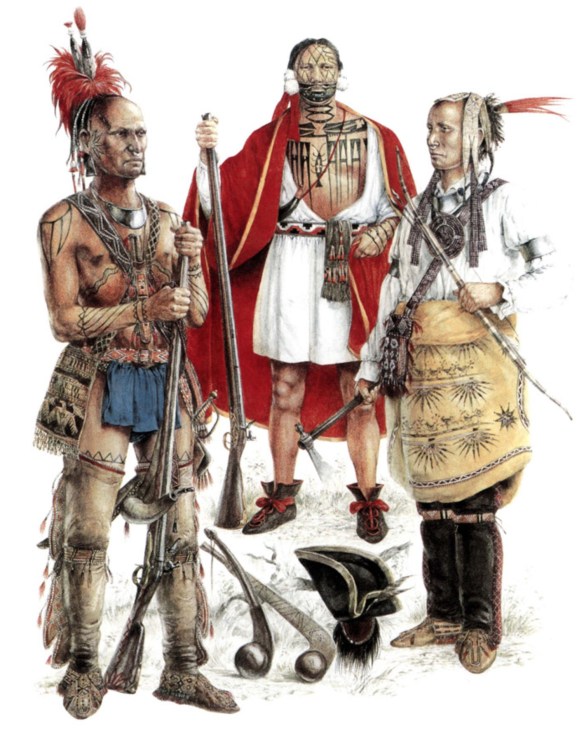

British-allied American Indians of the 18th century. On the left is an Iroquois warrior from about 1759. He is tattooed) and is armed with a painted trade musket. The Mohawk in the center is from the early 18th century) and is carrying a Hudson Valley fowling piece. He has complex tattoos on his face and body) and wears ear ornaments of swan down. He has a European blanket and shirt. On the right is a Mohawk warrior from about 1764. He carries a bow and arrows and a trade tomahawk. He wears feather and quillwork head ornaments, wampum ear ornaments and a ‘gorget.’ In the foreground are ball-headed clubs and a red-painted scalp with decorative stretcher rim. Richard Hook

Woodland American Indian men seem to have revered war above all else and, despite the great message of peace enshrined in the Iroquois league’s constitution, a conflict between the old men and the young over war policy was endemic. The councils could only adopt a policy of peace or neutrality; they could not force young men to observe it. War had been a major cause of the decline of the native population during the 17th century, for which the Iroquois compensated by the adoption of captives; in fact, war parties were often organized for this purpose. So despite the ideal that men were brothers and that killing should stop, the Iroquois were the major native disruptive military force in the northeast.

A warrior who wished to lead a war party would send a messenger with tobacco to ask others to join his expedition. The messenger would explain the purpose of the expedition followed by a ceremonial smoking of the pipe with those who enlisted. Later the warriors arrived near the camp of the leaders, who prepared a feast asking for a final pledge of support. The leader usually appointed lieutenants to act as his aides during the proposed raids. War dances and striking-the-warpost ceremonies were held before the war party left the camp together with the collection of ‘medicine,’ and materials for making and repairing moccasins. Amongst many of the eastern tribes parched corn was the standard provision of the warrior when on the trail; when mixed with maple-sugar it provided quick sustenance. The final event before the departure of the war party was often the dog feast, which was considered as a final pledge to meet the full fortunes of war. Dog war feasts were not acts of piety. They were organized by the warrior or clan societies in order to receive blessings from spirits. The dogs would be killed, singed, then boiled, and prepared in the same way as deer. The meat symbolized the flesh of captives that they might later eat, these enemies being compared to dogs. The attendant ceremonies, involving the ritual use of tobacco, evoked help from the night spirits, and also the bear and buffalo spirits.

On the warriors’ journey to the enemy village many songs and dances were held at the nightly camps, the warriors frequently singing of their former victories. The pipe bearer, a noted warrior, often led the war party with the leader walking last. A Chippewa war party could travel 25 miles a day. As the warriors neared the enemy they began preparations for actual warfare: singing medicine songs, making litters for the wounded, and designating individuals to carry extra supplies of medicine, corn, and water. An eagle-feather banner was often carried by one of the bravest warriors during the fight; another beat a drum to inspire his comrades.

The warriors would array themselves in the most colorful body-painting, trappings, feathers, and charms for the attack, which was often made at daybreak after taking ambush positions near the enemy village. The attackers usually rushed the enemy while they were sleeping. Occasionally one warrior might inspire the others by making himself a target, throwing away his weapons and clothing, and charging the enemy.

Returning victorious war parties sent runners in advance to carry the news of the warriors’ approach to their home village. The women would meet the warriors and carry the scalps, painted red, fastened inside hoops on the end of poles; frequently scalps were given to the women. The women led the procession, waving the scalps and singing, into the village. After the return preparations were made to hold a victory dance, and a feast of dried meat, wild rice, and maple sugar followed. The victory or scalp dance seems to have been common to almost every tribe in eastern North America. Wives and sweethearts of warriors usually carried the poles with the attached scalps at celebrations in neighboring villages. Unsuccessful war parties were generally ignored by villagers.

Amongst the Iroquoian tribes the taking of prisoners was an important part of warfare. They were often adopted into families who had lost warriors in battle, thus helping to maintain population strength. Ceremonial torture of prisoners and the eating of vital organs were also reported by early observers of the Iroquois.

The war dance was usually performed on special occasions such as council meetings to recall past deeds. In the dance itself attitudes of battle, watching, listening, acts of striking the foe, and throwing the tomahawk added to the war songs, rapid drumming, recitals, and speeches, giving the effect of passion, excitement, and violence. Most deeds of valor were recorded by symbols worn in public, usually eagle feathers worn upright, crosswise, hanging down, or colored red. Other warrior insignia were armbands, ankle and knee bands of skunk or otter skin, painted legs, painted hand designs on body or face, and raven’s skin around the neck. Sometimes the skulls of slain enemies were used as lodge weights, and their flayed skins were used as mats and doorflaps.

The Woodland American Indians fought bravely to defend their lands from neighboring tribes and whites. Their methods of warfare were culturally determined, and any atrocities committed were equally matched by their foes. The torture and burning of captives were often abandoned at the instigation of their own chiefs. Scalping was a New World custom, although it was later much encouraged by the payment of bounties by the English and French. However, killing and scalping were sometimes secondary objectives to prisoner-taking by Iroquois war parties. Scalping for bounty became a feature of white frontier life, as did the severing of heads. King Philip’s head was carried to Plymouth at the close of the 1675-76 war, where it was placed on a pole and remained exposed for a generation as a reminder to Indians and whites of the brutality of colonial warfare.

The disruptive use of gifts by both the French and the British during the 18th century did much to undermine the stability of the frontier and the dependability of American Indian auxiliaries. Braddock’s Indian scouts reconnoitering Fort Duquesne reported few men at the fort; following the death of the leader’s son by friendly fire only constant presents bribed the scouts to continue their duties, and they did so with little enthusiasm. A better understanding and treatment of the Indian allies by the British could probably have avoided the ambush of the column at Monongahela altogether.

Before the trade tomahawk and gun came into popular use by the eastern Indians, their principal weapons were the bow, the stone tomahawk, and the war club. The war club was a heavy weapon, usually made of ironwood or maple, with a large ball or knot at the end. Some antique clubs in museums have a warrior’s face carved on the ball, sometimes with inlaid wampum (beads cut from the shell of the clam or conch), a long-tailed carved serpent on the top of the ball adjoining the shaft, and a cross motif. The shafts were also occasionally carved with war records and decorated. It appears to have been a devastating weapon at close quarters.

In the Great Lakes region the so-called “gun stock club” was popular, often having a sharp-pointed horn or steel trade spike at the shoulder. These were largely replaced with the trade tomahawk of English, French, or later American manufacture in iron or steeL Originally of a hatchet form, these later incorporated a pipe bowl, thus symbolizing a dual role in peace and war: to smoke – to parley; to bury it – peace; to raise it – deadly war.

Poisoned blow-gun arrows were used by the Cherokee and Iroquois but not to any extent in the major conflicts, and perhaps for hunting only. Bows were usually of one piece, made from ash, hickory, or oak. Arrows had delicately chipped triangular chert heads, and were usually kept in sheaths or quivers of cornhusk or skins. Early reports suggest that a type of wooden slatted armor made of tied rods was used by the Huron and Iroquois.

The gun replaced the bow throughout most of the eastern regions between about 1640 and the late 17th century, and partly rendered obsolete the bow and arrow and rod armor. However, as late as 1842 (due to lack of ammunition) an eyewitness reported that a battle between Chippewa and Sioux was waged with club and scalping knife.

Between the I 7th century and early 19th centuries the practice of American Indian warfare changed little. A warrior’s equipment in later years included a blanket, extra moccasins, a tumpline used as a prisoner tie, a rifle, powder horn, bullet bag, and his own medicine. Delaware and Shawnee scouts in the US Army out west are said to have administered warrior medicine to white soldiers. The calumet ceremony was often performed for war and peace. It appears to have been of Mississippian origin and spread east to the Ottawa via most central tribes, together with the ritual use of tobacco and steatite and catlinite pipe bowls. Calumets were highly decorated wands of feathers, painted tubes with animal parts (including the heads and necks of birds) with or without the pipe. The use of the calumet and pipe for ritual smoking at treaty councils led to the term “peace pipe:’

Although the horse was adopted by the eastern tribes as a beast of burden, there seems to be little reference to its use in warfare except in the later 18th and early 19th centuries and particularly by the western tribes Sauk, Fox, Winnebago, etc. However, the Iroquois and Cherokee had large numbers of horses from the mid-18th century on.

The Iroquois conquered or exterminated all the tribes upon their immediate borders and by 1680 had turned their arms against more distant tribes, the Illinois, Catawba, and Cherokee. According to Iroquois tradition the Cherokee were the original aggressors, having attacked and plundered a Seneca Iroquois hunting party, while in another story they are represented as having violated a peace treaty by the murder of Iroquois delegates. The Iroquois war party usually took 20 days at least to reach the edge of Cherokee territory. Such a war party was small in number, as the distance was too great for a large expedition. The Cherokee often retaliated by individual exploits, a single warrior going hundreds of miles to strike a blow which was sure to be promptly answered by a war party from the north. A formal and final peace treaty between the two tribes was arranged through the efforts of Sir William Johnson in 1768.

About the year 1700 the Iroquois reached the apogee of their empire. From the start their relationship with the French was difficult, and from 1640 to 1700 a constant warfare was maintained, broken by periods of negotiated peace, the exchange of prisoners, and periods of missionary influence, which drew a portion of the Mohawks from their homelands to Canada. Their friendship with the English remained largely unbroken during the 17th century, but during the 18th century frontier politics were such that the league weakened and individual tribes no longer acted in one accord with league policy.

The Jesuits had established missions in eastern Canada by 1639, and by 1700 they were as far west as the Mississippi river. Thus France had a secure route to its southern territories, and secured French dominance of the Great Lakes fur trade until 176I. New France now encircled the Thirteen Colonies through the western wilderness. However, it was not always a friendly relationship between the French and the various American Indian tribes and several wars resulted with the Mesquakie (Fox), Sauk, Dakota (Sioux), Huron, and Chickasaw. While inter-tribal warfare seems always to have been the norm, the arrival of the Europeans added to inter-tribal rivalry within the fur trade. Indeed, the Iroquois’ conquests seem to have been largely to establish their superiority in such commerce. At times Indians took their furs to the British posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the far north, or even to Albany. By the 1730s the focal point of Indian and frontier colonial warfare was the Ohio River Valley, now populated along its tributaries by tribes forced across the Appalachian mountains by white population pressure. These were principally the Delaware and Shawnee, with portions of many tribes forming a multi-tribal population, including fragments of all six Iroquois tribes, Mahican, New England groups, Abenaki, and Chippewa (Mississauga).

American Indian Tactics

Though apparently crudely armed by European standards, American Indians had an undeniable advantage in North American warfare. Their knowledge of the forests and wilderness of their homeland was built up over centuries, and they could use the topography against any enemy. Having hunted since childhood, Indian warriors were well used to traveling vast distances at speed, dealing with fatigue and hazard, and being aware of every detail of their surroundings. They were lightly armed, highly mobile fighters, able to disappear into the environment at will, and supply themselves from their surroundings while on campaign for extended periods. Complete command of stealth tactics made Indians invaluable as scouts, and gatherers of intelligence. Colonial military leaders learned that spying on, and defeating, Indian warriors in battle was only possible with the expertise and knowledge of other Indians. Eventually, native scouts and tactical knowledge became legendary, and success in the Revolutionary War was partly attributed to the use of American Indian tactics and stealth.