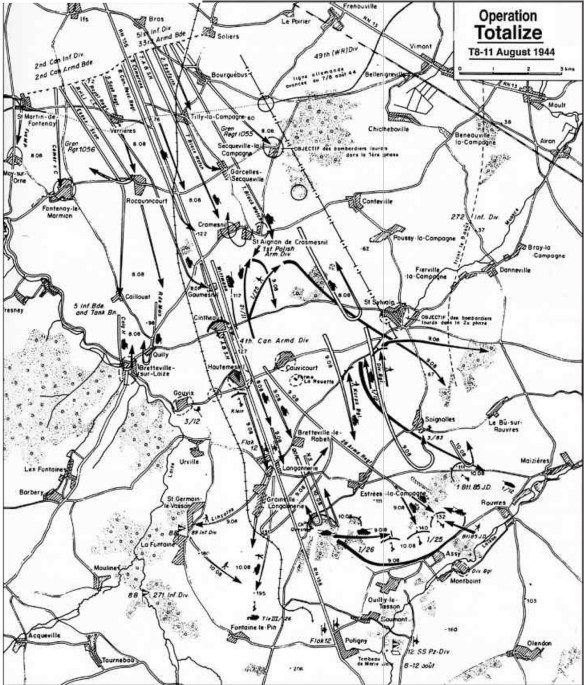

Phase I of the operation had allowed the Allies to capture May, Fontenay-le-Marmion, Rocquancourt, Garcelles, Secqueville, and even Saint-Aignan, which would play an important role at the beginning of the next phase. At the start of Phase II, the HJ Division’s counter-attack using Tigers, Panzer IVs (I./12) and the KG Waldmüller would fail. However, over the next two days the 4th Canadian Armoured Division would suffer a disaster at Hill 140 (east) and heavy losses to the west at Hill 195, with the failure marking the end of Operation Totalize.

Kurt Meyer took command of 12.SS-Panzer-Division following the death of Fritz Witt. He attempted to stem the rush of Allied armoured vehicles with skill and determination.

Phase II

The Canadians from 4AD assembled between Fleury-sur-Orne and the main road, with the exception of a tank battalion which would advance east of the road, while the Poles gathered to the south-east of Cormelles . This new attack would be preceded by a bombardment scheduled between 12:26 and 13:55. However, the Eighth US Air Force did not reach its targets until 12:55. The Bomb Line passed through the great Aucrais quarry, at Caillouet, in the west, to Robertmesnil. But once again, the bombardment would hit Allied units. The batteries of III.Flak-Korps opened fire against this armada, even though they were already coming under fire from Allied artillery, managing to take down nine four-engined B-17s. A large number of aircraft were unable reach their targets and out of 658 bombers, only 497 aircraft managed to drop a total of 1,487 tons of bombs. One of the lead bombers became disorientated and dropped its load on the Poles positioned in the suburb of Vaucelles, south of Caen, resulting in thirty-six casualties (eight killed and twenty-eight wounded). The total Allied casualties from such bombarding errors amounted to 315 (Polish division and 3rd Canadian ID), of which sixty-five were killed and 250 wounded. In addition, four guns and fifty-five vehicles were destroyed, causing profound disruption. The head of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, Major General Keller, was among the wounded and had to be evacuated. In The Story of the Algonquin Regiment, Major G.L. Cassidy writes: ‘The generally accepted idea was that the Germans had captured some of the flying fortresses and had joined the armada for a surprise bombardment. Whatever the reason, the depressing event was experienced by all of the troops, who then feared that the whole operation would be compromised.’

In his account, Kurt Meyers describes the decision he took with Waldmüller to counter-attack:

I met Waldmüller north of Brettevillele-Rabet and we moved to Cintheaux together to orientate ourselves. Wittman’s Tigers were already east of Cintheaux, hidden behind the hedgerows, and had not engaged in the fire fight up to that point. Cintheaux was under artillery fire, but the open terrain around it did not seem to be receiving any fire. From the northern outskirts of the village we saw the dense columns of tanks north of the road to Bretteville-sur-Laize. It was the same view to the south of Garcelles and to the edge of the wood located to the south-east of the area. The sight took our breath away. We did not understand the Canadians’ actions, why did such a powerful armoured force not continue its attack? Waldmüller and I decided that we must not let these ‘squadrons’ of tanks reach us and the enemy tanks must not be allowed to attack. On either side of the road, an armoured division stood ready for attack. The offensive must not resume; we had to seize the initiative. I decided to defend Cintheaux with the forces already in position there, and to attack east of the road at lightning speed road using all the available soldiers in order to upset the enemy’s plans. The wood located to the south-east of Garcelles was our objective … During my last discussion with Waldmüller and Wittmann we had seen a single bomber flying over the area several times, followed by the flares. I gave the order to attack immediately so that we could get out of the area that was going to be bombed. I shook Michel Wittmann’s hand once more and remind him that the situation was particularly critical. The good man laughed his youthful laugh and climbed into his Tiger, which up until that point had destroyed 138 enemy tanks. Would he increase this score, or would he be the victim this time?

The panzers rapidly rolled north, crossing the open terrain at full speed and using the undulating ground to shoot at the enemy tanks. The grenadiers followed the panzer attack and advanced towards their objective. I was at the northern edge of Cintheaux when the enemy artillery launched a destructive bombardment on the attacking panzers. Michel Wittmann’s panzer fired in the midst of the enemy fire. I knew his tactics on such occasions: keep going, do not stop! All of the panzers rushed into the steel hell; they knew they had to prevent the enemy from attacking and disrupt his plans. Waldmüller followed with his infantrymen; the brave grenadiers following their officers.

A machine gunner cried out to me in the all-destructive artillery fire. He pointed to the north-west. Speechless when confronted with the overwhelming power of the Allies, I observed an endless chain of large four-engine bombers approaching us. The ironic remarks of a few grenadiers allowed us forget the great danger for a fraction of a second. A young soldier from Berlin shouted out, ‘What an honour, Churchill has sent a bomber for each of us!’ Actually he was quite right. More bombers were approaching than we had grenadiers on the ground!

There was only one way to save ourselves at that point: get out and move into the open terrain. The men defending Cintheaux left the estate at lightning speed and waited for the bombs to drop in the fields to the north. We had been right: village after village was being flattened. It did not take very long before large fires sent flames skywards. We noted with pleasure that the American bombing fleet had also hit the Canadians. The last waves flew over the vigorously attacking KG Waldmüller, without dropping a single bomb on an armoured vehicle. The aircrew had engaged the targets they had been assigned without worrying about how the situation might have changed in the meantime…

Kampfgruppe Waldmüller had approached the patch of woods and was already fighting the Polish infantry. The grim duel of tank against tank was being conducted between the vehicles of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and the Tigers of Michel Wittmann. Occasionally, the Tigers could hardly be recognised. Well-guided artillery fire was being directed against the Tigers and the Panthers [author’s note: these had to be Panzer IVs]. In the meantime, we had reoccupied our old positions in the ruins of Cintheaux. The estate was being attacked from due north and came under the direct fire of the Canadian tanks. Flanking fire from a few of Wittmann’s Tigers helped to keep the Shermans away from Cintheaux. We observed strong enemy movements 1 kilometre in front of us, heading in the direction of Bretteville-sur-Laize. Attack after attack collapsed in front of us. We had incomparable luck: our opponents did not launch a single concentrated attack against us. The Divisions-Begleit-Kompanie reported its location as west of Saint-Sylvain. It was fighting the lead elements of the 1st Polish Armoured Division and had destroyed several armoured vehicles. The Poles no longer attempted to move out of the woods at Cramesnil … The fighting had lasted several hours. The wounded were collected south of Cintheaux and evacuated under enemy fire.

As we know, Saint-Aignan was occupied by the 1st Black Watch from 06:00, along with tanks from 148th RAC and 144th RAC or 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry (1st Northants), as well as tanks from the 33rd Armoured Brigade. The British now occupied positions north and east of Saint-Aignan, with the 1st Northants’ CP being located in an orchard north of the locality. The tank unit’s A Squadron was in position south of Saint-Aignan and in the small wood to the south-west, facing Cintheaux. The squadron had three sections made up of three classic Sherman tanks and a Sherman Firefly tank. The latter was armed with a 76.2 mm long barrel and used APDS tank shells that could pierce 19.2 cm armour plating from 1,000 metres. It was this A Squadron from the Northants who would face the Tigers’ counter-attack, and we will return to these units later.

It is important to remember the course of events before this attack. The Tiger’s 2nd Company had been engaged with KG Wünsche’s Panther tanks against the Grimbosq bridgehead and, despite being recalled, would not be available to counter-attack. Instead, the Tigers from 3./s.SS-Panzer-Abteilung 101 would be committed. Around 06:00, the head of 3rd Company, SS-Hauptsturmführer Heurich, had gone north with his vehicle without receiving orders from Wittmann, who was in command of the Tiger tank battalion under the authority of KG Wünsche. The aide-de-camp, SS-Hauptscharführer Höflinger, went to stop Heurich and told him to wait for orders. At about 07:00, a seemingly nervous Wittmann, (unusual for this normally calm and balanced Bavarian), went first to the battalion’s headquarters with Doctor Rabe and then to 3rd Company. He arrived at Cintheaux around 11:00 where he found the Tigers belonging to SS-Untersturmführer Willi Iriohn, SS-Hauptsturmführer Franz Heurich, SS Oberscharführer Rolf von Westernhagen, SS-Oberscharführer Peter Kisters and SS-Unterscharführer Otto Blasé (all members of 3rd Company), as well as those of SS-Untersturmführer Helmut Dollinger (communications officer) and SS-Hauptscharführer Hans Höflinger (aide-de-camp). Together with the Tiger of SS-Hauptsturmführer Michael Wittmann, this meant that only eight Tiger tanks were ready for the counter-attack.

A few weeks later, SS-Hauptscharführer Höflinger would provide the following testimony of these few hours:

I was woken up exceptionally early at dawn on this hard day. This was because Heurich’s company had left its position, without orders from the Kommandeur, and advanced on the road towards Caen. Michel immediately wanted to know what was going on and for that reason, as I was the aide-de-camp, I had to get to the company as soon as possible and find out what was happening. I did this and then reported to Michel. After a brief pause, which I was accustomed to on his part, he ate his breakfast, a little nervously, and then ordered me to take the two staff tanks to where Heurich’s company was located. This I did before returning very quickly in my Schwimmwagen to report back to Michel.

We then left together, him in a Kübelwagen, me in a Schwimmwagen, for Meyer’s command post to attend a meeting. When it was over, we discussed whether or not we would accompany the attack. The communications officer, Untersturmführer Dollinger, was with us. All of a sudden, Michel said, ‘I have to go because Heurich will not.’ That day, Heurich led his first fight and it was dangerous. After a few hours, we returned to the panzers, which were on the road at Cintheaux. I did not have to accompany the attack at first, but all of a sudden the situation changed. It made me nervous because Michel was uncertain in his decisions. Shortly afterwards, we climbed into our engines and camouflaged them from any aerial observation.

SS-Hauptsturmführer Wittmann set off in Tiger 007, accompanied by the experienced SS-Unterscharführers Hein Reimers (driver) and Karl Wagner (gunner), both veterans of the Russian Campaign, as was SS-Sturmmann Rudi Herschel (radio operator). The crew was completed by SS-Sturmmann Günter Weber (loader). Wittmann, Dollinger and Iriohno’s Tigers were to the right of the RN158 road, and were probably joined by Kisters’ and a fifth Tiger. Höflinger and von Westernhagen’s Tigers advanced down the left side of the road, the company commander’s vehicle (Heurich), also advanced on the right, but behind the others. On the right, over to the east, was KG Waldmüller with I./25 and the Panzer IVs from II./SS-Panzer-Regiment 12, who moved in a northerly and north-easterly direction. What follows is the testimony of Hans Höflinger, who describes the Tiger attack:

We set off together, Michael to the right of the road and myself on the left. There were still four of us [Tigers], with von Westernhagen on the same side as me. There was a small wood about 800 metres to the right of Michael that would play at part in our destiny. We drove for 1.5 km and I received a radio message from Michael which only confirmed my apprehension regarding the small wood. We came under heavy anti-tank fire and Michel once again tried to contact me on the radio, but the message was interrupted. When I looked to the right, I realised that Michael’s panzer had stopped. I sent him a radio message but received no answer. My panzer then took a direct hit and I had to evacuate immediately as the vehicle was already beginning to burn fiercely. I lept out with my crew and we headed for the rear. I looked at what was happening and was completely shocked; five of our panzers had been destroyed. The turret on Michael’s tank was turned towards the right and hanging forward. None of the crew was left. Along with Heurich, I now began looking for who still had his panzer. I approached Michael’s panzer in von Westernhagen’s vehicle but couldn’t reach it. Dr. Rabe also tried, but in vain … The exact time was 12:55, along the Falaise-Caen road, near Cintheaux.

The history of the 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry, written by one of its veterans, Ken Tout (A Fine Night for Tanks, the Road to Falaise, Sutton Publishing, 1998) provides a better explanation of what happened. After a ‘night of horror’ (remembering that in spite of the overwhelming Allied superiority and the disintegration of certain elements of the 89.Infanterie-Division, which Kurt Meyer had witnessed), many of the division’s elements fought back with great resistance, clinging on to certain villages, such as May, causing heavy casualties for the Allies who had attacked in the middle of the night. After leaving Cormelles, the unit passed through Bourguébus and crossed the start line, before reaching Garcelles then Saint-Aignan. The 1st Northants entered Saint-Aignant early in the morning, along with a tank unit from the 33rd Armoured Brigade (independent), accompanied by the 1st Black Watch, the infantry unit of the 51st Division. The tanks took up position in a circular arc south of Saint-Aignan: Captain Boardman’s A Squadron pointing towards the south and west (towards the Falaise road) and C Squadron pointing towards the south and east, towards the open terrain. B Squadron was kept in reserve, to the rear, while infantry from companies A and B, 1st Black Watch, took up position in trenches either behind or close to the tanks.

For C Squadron, the morning was still calm and peaceful as the sun broke through the early mist. In front of the village, the fields gently descended down to a thick hedge punctuated by large trees. Afterwards, the ground opened up towards the buildings of the Robertmesnil farm. Everything was calm, even though the unit was only 3 miles from the front line. No. 2 Troop from C Squadron advanced to a position between the trees in the hedge, without spotting any threat. While all eyes were surveying the terrain, discussions were taking place over the internal radio: ‘Why are we not going to take the other ridge?’ To which Commander Ken Snowdon replied, ‘We are already quite far forward and are sufficiently isolated enough here!’ Breakfast was taken while branches were cut down from the trees to help camouflage the tanks – an important precaution given what was to come. The illusion of peace lasted until 10:30, when mortar bombs began to hit the area. Over the radio came the message, ‘Medics forward, “Big Sunray” is wounded’. “Big Sunray” was the nickname of the 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry’s leader, Lieutenant Colonel Doug Forster. Stretcher carriers ran to the middle of the CP. Forster had been speaking with the Hon. Peter Brassey, head of B Squadron, when they were both injured by a mortar shell; Forster in the neck and Brassey in his hand. Major Wyckeman now took command of the unit, while the deputy commander was a Welshman, Captain Llewellyn. Forster had been a retired Hussar, but had gone back into service at the beginning of the war. His authority had helped keep the unit together and his loss was a hard blow for the Yeomen to bear.