A new generation of armoured infantry transports was born as a result of Operation Totalize: the ‘Kangaroos’, which were created using the chassis of Canadian Ram tanks. The REME (Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers) had already created this type of vehicle in early July to repair other armoured vehicles abandoned in No Man’s Land. This one is from the 30th Armoured Brigade Workshop, 79th Armoured Division.

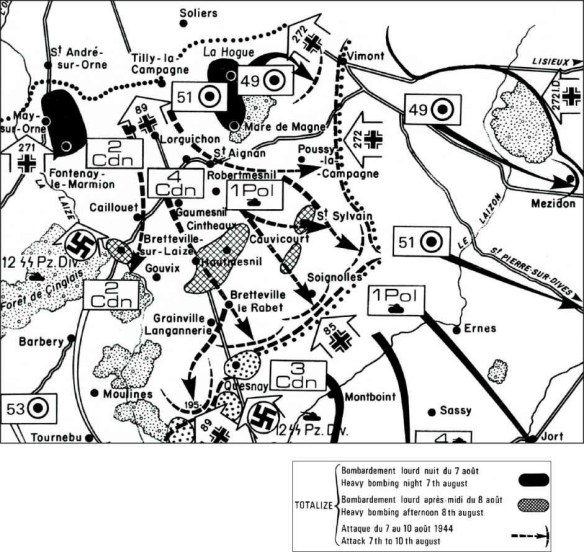

At 23:30 on 7 August, the leader of II Canadian Corps, Lieutenant General Simonds, launched the offensive following the preliminary bombardment. In total, 1,020 RAF heavy bombers had dropped 3,462 tons of bombs on targets that had been marked by coloured artillery shells laid on the edges of the area to be hit, thus framing the corridor for the offensive. In the west; May-sur-Orne and Fontenay-le-Marmion. To the east; La Hogue, Secqueville-la-Campagne, Garcelles-Secqueville and Saint-Aignan-Cramesnil. The smoke obscured the entire area meaning that a third of the bombs could not be dropped. In addition, ten planes were shot down by Flak and the Grenadier-Regiment 1055, on the right flank, thus resulting in the bombs actually landing on Allied positions. It was not to be the last time such ‘friendly fire’ affected Allied troops in this operation. Seeing the bombs falling on their adversaries, the men from 89.Infanterie-Division come out of their individual foxholes to admire the show. During the bombardments on the left flank (west of the RN178 road), on the positions of Oberst Roesler’s Grenadier-Regiment 1056, a platoon left its position and advanced forward, taking the Canadian soldiers who were ready to attack by surprise. The grenadiers then returned to their positions after the bombing had finished, bringing Canadian prisoners back with them.

Lieutenant General Simonds had planned the operation around an unusual time frame and with equally unusual methods; a nocturnal aerial bombardment before an equally nocturnal attack. Errors were avoidable. The battlefield was once more (as it was for Operation Spring) illuminated by artificial lights, with headlights directed towards the sky creating an ‘artificial moonlight’ on both sides of the RN158 road, aided by the green glows of the marker shells that created a central boundary between the two forces of attack. It was time for the offensive to begin. To the west of the RN58, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division moved into the attack, preceded by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, in four columns. To the east, the 51st Highland Division, preceded by the 33rd British Armoured Brigade, in two columns. Each column was preceded by two Sherman tank sections, along with two flail tank sections to clear any mines, and engineers. Each column included 1,900 men and 200 armoured vehicles. A further group of tanks followed behind to support the armoured and infantry columns. The exploding shells illuminating the clouds from underneath made it easy for the men to navigate, as they followed the beams of light and took their bearings on their compasses. The advance was marked with conventional coloured lamps placed on stakes 1.5 metres high every 5 metres. The direction they needed to follow was given by the DCA tracing shells, which were continually aimed due south.

Allied artillery only opened fire at 23:45, when the two parallel forces approached their starting line (the road from Saint-André-sur-Orne to Hubert-Folie). On a front 3,700 meters wide, 300 guns launched an artillery barrage that advanced 200 metres per minute; all of the units were mechanised, hence the fast pace. Lessons had been learned from Operation Goodwood’s failure : the British and Canadians had not had armoured personnel carriers such as the excellent German SPWs. In the rush, the 150 mm guns from self-propelled ‘Priests’ were removed and reinforced with armour plates , converting them for armoured troop transport. They were consequently nicknamed ‘Unfrocked Priests ‘or ‘Kangaroos’ and carried the infantry alongside the tanks. The Allies also had 720 guns for various targets, some even reaching the 89.Infanterie-Division’s CP located at Bretteville-sur-Laize. But despite all these precautions, many columns went the wrong way and arrived late at their objectives. This was, in part, due to the lack of visibility caused by the fog, smoke, and dust raised by the caterpillars, but also because of fire from isolated resistance pockets and artillery. The columns were distended, with some vehicles ending up in other columns and being hit by ‘friendly fire’, while some lead vehicles fell into bomb craters and blocked the way.

To the west, 4th Brigade, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, was at the forefront of the advance in the midst of the fog and dust. It advanced in four columns behind the flail tanks. Each was centred on the brigade’s three battalions and on the 8th reconnaissance regiment (14th Canadian Hussars). Seventy-seven Kangaroos carried the infantry companies, accompanied by the Sherman tanks from 2nd Armoured Brigade, followed by the Tank-Destroyers from 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, and the Bren-Carriers of the Toronto Scottish Regiment (machine guns). Meanwhile, 5th Brigade remained in reserve, while 6th Brigade would have the task of neutralising the German defensive points at May-sur-Orne (the objective for the Fusiliers Mont-Royal, with the support of flame-throwing tanks), Rocquancourt (South Saskatchewan) and Fontenay-le-Marmion (Camerons).

The infantry from 6th Canadian Brigade, which was on foot, came into difficulty as they attacked a part of the front which was only defended by two infantry battalions from the GR 1056 (Oberst Roesler) and some assault cannons. However, Rocquancourt was taken at 0:45 by the South Saskatchwan. The attack by the Fusiliers Mont-Royal was pushed back at first; the bombardments having clearly not been able to crush the powerful resistance of Colonel Roesler’s grenadiers. May-sur-Orne would not be fully taken until 16:00 on 8 August and would then only fall with tank support from the 1st Hussars. Roesler’s grenadiers had remained determined, in spite of the deluge of fire they had endured.

At Rocquancourt, which had been reduced to a heap of ruins (although the church bell tower still stood), a force of nearly 300 armoured vehicles advanced through the middle of the night in the smoke and dust, as well as through German fire and smoke bombs, all of which caused the armoured vehicles from 4th Brigade to veer off course. The Essex Scottish had to take Caillouet, but needed to reorganise near Rocquancourt at 8:55, losing vehicles under fire in the process, and would not reach its destination until noon. The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI) was halted by artillery fire at Gaumesnil quarry and had to dig in 1.5 km north-west of the area. Indeed, by dawn on 8 August the Royal Regiment of Canada would be the only one to arrive at its objective east of Gaumesnil, but it still suffered losses. Nevertheless .

To the east of the RN158 road, the 51st Highland Division advanced from the Bourguébus/Hubert-Folie sector in two armoured columns, following the same principle as the Canadians. Its 154th Brigade (1st and 7th Black Watch, 7th Argylls) on Kangaroos, 350 armoured vehicles and tanks, accompanied by the 33rd Armoured Brigade in two columns of four advance vehicles only 20 metres apart, advanced under the DCA’s spotlight and via the coloured shells. However, the attack on La Hogue was pushed back at first by elements of the 89.Infanterie-Division, supported on the right flank by the 272.Infanterie-Division. But when Hill 75, located to the west of Secqueville and also held with the support of 272.Infanterie-Division, was finally lost, elements of the 89.Ifanterie-Division who had fought there fell back to their second position on either side of Saint-Aignan. The attack also now clashed with the left flank of 272.Infanterie-Division, and the wood east of Secqueville was taken by the Germans. A German counter-attack was repulsed and the 272.Infanterie-Division consequently pulled its left flank back to Chicheboville/Conteville. The 1st Black Watch finally reached its objectives at 06:00, including Saint-Aignan. The 7th Black Watch reached Garcelles-Secqueville, which it would hold with the Churchill tanks from the 148th RAC, while the 7th Argylls and the Churchill tanks of the King’s Own (whose commander was killed in his tank) would cling on to Cramesnil from 04:30.

After the capture of Saint-Aignan, British tanks attacked in an easterly direction, but were beaten back near Conteville and Poussy. Behind the attacking force, the 132nd Brigade (2nd and 5th Seaforth Highlanders, Camerons) had to clear the areas that the two armoured columns had missed, on foot. At Tilly-la-Campagne, the 2nd Seaforth was repulsed by grenadiers from Grenadier-Regiment 1055 (89th), who clung on to the ruined village. Despite reinforcements, the 5th Seaforth was still unable to succeed and required the help of a tank platoon from the 148th RAC, who attacked the German grenadiers from the rear. At 09:30, an officer and thirty survivors from Grenadier-Regiment 1055 finally surrendered.

The Two Armoured Brigades

The first phase of the offensive, led by infantry divisions, was supported by two armoured brigades. To the west, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division was supported by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade with three tank regiments: the 6th Armoured Regiment (also called the First Hussars); the 10th Armoured Regiment (The Fort Garry Horse) and the 27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment). To the east, the British Armoured Brigade who supported the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division was the 33rd Armoured Brigade, also with three tank regiments: 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry (1st Northants); the 144th Regiment RAC (until 22 August) and the 148th Regiment RAC (until 16 August).

8 August

Faced with this stampede and deluge of fire, the Kommandeur of 12.SS-Panzer-Division Hitlerjugend, SS-Oberführer Kurt Meyer, headed out over the terrain in his Volkswagen before dawn, accompanied by liaison officers, to assess the situation. The information they gathered together was not reassuring: the 89.Infanterie-Division’s positions would be broken along a wide front and although some of the support points would still hold, contact with them would be broken. Tanks were reported in Saint-Aignan and if the breakthrough succeeded, the only option was to establish a new defensive line behind the Laison sector, on either side of Potigny. This could only be done effectively with the help of a new division, the 85.Infanterie-Division, which was on its way (on foot and by bicycle), and whose first elements were already in Trun. However, time was needed in order for it to reach the front line and stop the offensive to the far north, or at least slow down the Allied advance. For the moment, Kurt Meyer (nicknamed Panzermeyer) saw only defeated men who had ‘cracked’ under the violence of the bombardment, and who had retreated south in disarray. Some of the men were bravely trying to hold the ruined villages along the front lines, clinging on for hours in front of the Allied steamroller of armoured vehicles and infantry. Some had even tried to counter-attack. But this vision of a routed army had a shocking effect on SS-Oberführer Meyer:

For the first time during these long, gruesome years of genocide, I was seeing German soldiers running away. They were unresponsive. They had been through hellfire and stumbled past us with fear-filled eyes. I looked at the leaderless groups in fascination. My uniform stuck to my body; the heavy burden of responsibility made me break out in a sweat. I suddenly realised that the fate of Falaise and the safety of both armies depended on my decision.

I stood up in the Volkswagen and moved in the direction of Caen. More and more confused soldiers approached me as they fled southwards, as I vainly tried to stabilise the collapsing front. The appalling bombardment had unnerved the units of the 89.Infanterie-Division. Rounds landed on the road, sweeping it empty. The retreat could only continue off to the sides of the road. I jumped out of the car and was alone in the middle of the road.

I slowly approached the front and addressed the fleeing soldiers. They were startled and stopped [what they were doing]. They looked at me incredulously, wondering how I could stand on the road armed with just a gun. The young soldiers probably thought I had cracked. But then they recognised me, turned around, and waved to their comrades to come and organise the defence around Cintheaux. The place had to be held at all costs to gain time for the Kampfgruppen; speed was imperative.

Measures had to be taken immediately in order to prevent a collapse of the German front in this sector. Panzermeyer met General der Panzertruppen Heinz Eberbach, the leader of the 5.Panzer-Armee, at Urville. Eberback wanted to get an idea of the situation near the advanced positions, agreeing with Meyer’s analysis and with his planned counter-attack. In the meantime, I.SS-Panzer-Korps had already ordered the Allied breakthrough to be halted and, if possible, pushed back:

– Reinforcements would be provided by the HJ Division’s 2nd panzer battalion (thirty-nine Panzer IVs) (II./SS-Pz.-Rgt.12) and a Tiger tank company (around ten). Kampfgruppe Waldmüller (III./26, III Battalion SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment 26) was to take the high ground south of Saint-Aignan (east of the RN178) in a counter-attack. The Korps-Begleit-Kompanie would be attached to KG Waldmüller on its right, and would also join the attack.

– The Divisions-Begleit-Kompanie (HJ Division), along with 1st Company, SS-Panzerjäger-Abteilung 12 (also attached to KG Waldmüller), would advance on Estrées and take the high ground to the west of Saint-Sylvain.

– KG Wünsche would immediately suspend its counter-attack near Grimbosq and Brieux, disengage, and then occupy the high ground west and north-west of Potigny. It would then defend the area between Laison and Laize (on the western flank of the Allied breakthrough).

– The HJ’s artillery regiment (SS-Pz.-Art.-Rgt.12), with SS-Werfer-Abteilung 12, would support the counter-attack along the positions near the main road.

– The Flak group (HJ Division) would establish an anti-tank barrier on both sides of the mainl road, at Bretteville-le-Rabet.

By noon, all of the first phase objectives of Operation Totalize had been achieved along a line exceeding 5-7 kilometres south of where the front had been the day before. To the west, the Canadians counted 344 losses, 72 in the initial (armoured) breakthrough and 262 infantrymen who had advanced on foot to try and liquidate the various pockets of resistance (May-sur-Orne would hold until 16:00). To the east, the 51st Highland Division suffered losses due to the tragic bombardment error (including 17 losses in the 5th Black Watch alone) and 260 casualties as of midnight on 8-9 August.

– The reconnaissance group (SS-Pz.Aufkl.-Abt.12), under the command of SS-Untersturmfürher Wienecke, would maintain contact with the left flank of 272.Infanterie-Division (to the east) and would reconnoitre the existing gap, most likely in a westerly direction.

The 12.SS-Panzer-Divsions’s CP was located in a place that in other conditions might have been rather romantic, being under the tomb of Marie Joly, at the Breche au Diable (just under 1 mile east of Potigny). Kurt Meyer would remain with KG Waldmüller during the counter-attack.

It is impossible to provide the numbers and positions of the Nebelwerfer (rocket launchers) and Luftwaffe Flak positions. The 12.SS-Panzer-Division’s former chief of staff, Hubert Meyer, stated that, ‘we knew the Werfer-Regiment 83’s (Werfer-Brigade 7) 3rd battery was in position near Soignoles (south of Saint-Sylvain) and covered an area from Saint-Sylvain to Urville to a depth of 7.5km. Other batteries from the 1st group had to be engaged in the same sector. KG Waldmüller set off to Brettevillele-Rabet to assemble there and the attack was to begin around 12:30.’ It is also important to note the presence of III.Flak-Korps in the west, in the Laize sector, which would play a significant role in the counter-attack with its formidable 88mm guns.

Phase II was now put into action. To the west, General George Kitching’s 4th Canadian Armoured Division (4 CAD) arrived to occupy the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division’s positions on its former starting line. To the east, General Stanislaw Maczek’s 1st Polish Armoured Division was positioned on the former starting line of the 51st Highland Division. These two armoured divisions had not yet experienced what it meant to be under fire, and it would prove to be a terrible baptism for the Canadian division. The 4 CAD was to be divided into three battle groups. The first was the Halpenny Force (under the orders of Lieutenant Colonel Halpenny, commander of the 22nd CAR), comprising of the 22nd Canadian Armoured Regiment (22nd CAR) or Canadian Grenadier Guards (CGG) with the LSR, the 96th Anti-Tank Battery and a squadron of flail tanks. They had little time to prepare; their orders only reaching them at 17:00 the day before (see Brigadier General William J. Patterson, Soldiers of the Queen, The Canadian Grenadier Guards of Montreal 1859-2009, p.232).

As for the division’s infantry brigade, Brigadier Megill’s 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade (the Algonquins) was still in the Vaucelles area (south of Caen) on the morning of 7 August. They had witnessed the night-time hell and were already knew what their objectives were: Bretteville-le-Rabet and Falaise. In the morning, their convoys had been hit on the road from Falaise to Ifs, where they had to wait for most of 8 August until the bombardment in the afternoon. The infantrymen of the Lincs’ (Lincoln and Welland) had left Caen on foot and remarked that at midnight, ‘the sky was as bright as daylight.’ In the middle of the morning on 8 August, they were ordered to head for Rocquancourt, and the regiment’s journal describes the march:

[It was] like a day of horror under the artillery fire; limestone buildings were pulverized, houses were without windows and roofs, and the air was polluted by the pestilence of death. The unit had to dig in again while the plans were developed at the brigade command post. The men had soon learned the necessity and routine of digging shelters because they were targeted by the mortars. They could even be hit by a shell in a trench. So you dug here and there for your own safety. It became your home. (Geoffrey Hages, The Lincs, a History of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment at War, 2007, pp.27-29).

In this sector the hard limestone was close to the surface, making the task of digging any form of shelter difficult, but the men would remain here until nightfall.