Tank crews from 4th Canadian Armoured Division gathered together south of Caen, at Vaucelles, Colombelles and Fleury, where these soldiers were photographed.

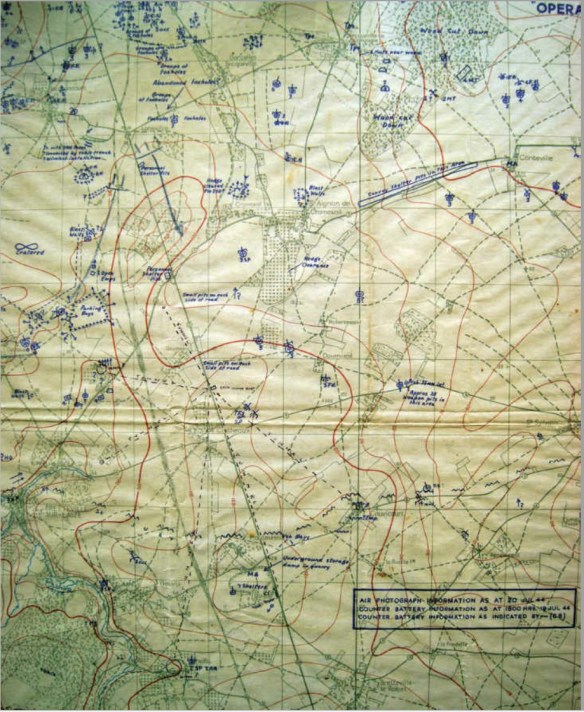

Excerpt from a rare Allied map prepared for Operation Spring, accurately detailing the German positions on both sides of the road leading from Caen to Falaise. From north to south, note the strong positions north-west of Garcelles-Secqueville, east of the main road. Rocquancourt appears to the west. A pencil inscription indicates the general direction along the axis of the main road. Further ahead, just before Cintheaux, a network of tunnels is marked on the map. The Allies knew the Germans’ ability to use such an underground network to come up behind their opponents, as the grenadiers from the Hohenstaufen had previously done in the area around May-sur-Orne. A network of trenches can also be seen in an arc around Hautmesnil. In the north-east corner (top right), note that the woods have been cut down and that the convoy shelter pits were sheltered by the opposite slope between Saint-Aignan-de-Cramesnil and Conteville.

This American map shows the 12th Army Group’s plan of attack on 8 August 1944. Even before the end of the German offensive at Mortain, the First US Army were ordered to advance on Domfront and Flers to join XXX (British) Corps which was advancing, with great difficultly, to Condé-sur-Noireau as part of Operation Bluecoat. Meanwhile, the Third US Army was ordered to circle behind the German Army, towards Alençon and Argentan, and join the II Canadian Corps, who had been ordered to take Falaise.

On 25 and 26 July 1944, the First US Army finally achieved the ‘Breakout’; the breakthrough along the Normandy front following Operation Cobra. The group then chased the Germans towards Coutances and Avranches, so as to not allow them to reconstitute a cohesive front. On its right, the Third US Army entered the line to advance on Brittany (to the west), and to the Loire region (to the east), on the back of the Normandy front. To aid this push on the German front, XXX Corps, supported to the west by VIII Corps (starting from the Caumont-l’Eventé salient), launched the ‘Bluecoat’ offensive through the rugged and difficult bocage [farmland criss-crossed by dense hedgerows, trees and sunken roads, which is typically associated with the Normandy landscape], which made any progress slow.

In order to try and cut the Allied forces in two Hitler launched Operation Lüttich, which involved a German counter-attack near the American positions at Mortain. However, because the attacked needed armoured units, these had to be removed from other areas along the front, thus weakening those areas in question. On 7 August 1944, 145 panzers were launched in this counter-attack and headed far to the west before having to retreat hastily following the failure of the offensive, which had unfortunately been launched just as II Canadian Corps was launching Operation Totalize in the area around Falaise. These 147 tanks would be sorely missed in the face of this new Allied offensive. South of Caen, where the 9.SS-Panzer-Division Hohenstaufen and 1.SS-Panzer-Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler had heroically resisted Operation Spring by holding onto the impregnable May-sur-Orne, the Troteval farm and Tilly-la-Campagne (names which now resounded in glory for the German Army), two weak divisions relieved the following panzer units; the 271.Infanterie-Division relieved the Hohenstaufen in order to deal with Operation Bluecoat, and the 89.Infanterie-Division relieved the Leibstandarte to participate in the counter attack at Mortain. The situation was in the Allies’ favour, especially as the Americans were now advancing towards the south of the Normandy front. It was now time for Montgomery to re-launch the attack on Falaise after the successive failures of Operations Goodwood and Spring. A carpet of bombs should be enough to settle the fate of the German support points, before the advance to the south could begin…

Beyond the former line of support points along the German front, the RN178 road runs straight towards Falaise over a gently undulating terrain of wheat fields. There are almost no obstacles, except for a few villages grouped together, small woods and bushes, but there are no hedges, as in the bocage. It is, therefore, an ideal ground for Allied armoured columns. However, there is a negative counterpart to all these advantages: the open terrain also favours the longest range of the German 88 guns, which were quite numerous in the sector, as well as the twenty Tiger tanks available in the area.

For Montgomery, the German sector located to the south of Caen remained of decisive importance, in spite of the failures of Operation Goodwood to the east of the town, then of Operation Spring to the south of it. He insisted on its importance in his directive of 6 August 1944, describing it as the ‘hinge’ of the German front. The situation for the German command would be particularly critical if the positions on either side of the road leading to Falaise, or even the town itself fell, ‘… tomorrow or during the next two days …’. Thus, the First Canadian Army decided to launch an offensive for the night of 7-8 August, with the aim of seizing Falaise. The offensive would be called Operation Totalize.

The operation was conceived following Montgomery’s M-516 directive of 4 August, which ordered the Canadian Army to launch a major offensive in the direction of Falaise from the area south of Caen:

[The] Purpose of the operation: a) The breakthrough of the enemy’s positions south and south-east of Caen. Gain as much ground as possible in the direction of Falaise in order to cut the enemy forces now facing the Second Army and hinder their retreat to the east, or make it impossible. (b) In general, destroy the enemy’s personnel and equipment in preparation for a possible extension of success.

The II Canadian Corps were to carry out this new offensive. After being strengthened since Operation Goodwood, at the beginning of August, it comprised of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, the 33rd British Armoured Brigade and the 1st Polish Armoured Division. It also needed strong air support. The corps would launch its attack across the area from La Hogue to May-sur-Orne, then pass through Tilly-la-Campagne, following the main line of the German front. However, the Allied Command believed that the Germans were expecting an attack in this sector, which was indeed the case, and so as a preliminary to this operation, the plan was to establish a bridgehead on the Orne, on the back of the German front line.

The main attack would be launched in three phases:

First phase: two infantry divisions (2nd Canadian ID and 51st British ID) would attack at night, without preliminary aerial support, in order to break through the German positions between La Hogue and Fontenay-le-Marmion.

Second phase: the withdrawal position between Saint-Sylvain and Hautmesnil would be broken through by an armoured division (4th Canadian Armoured Division) and an infantry division (3rd Canadian Infantry Division). This attack would be supported, during the day, by all medium and heavy bombers, as well as fighter-bombers, with heavy artillery available.

Third phase: this would be led by two armoured divisions, the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and the 1st Polish Armoured Division. Their mission would be to widen the gap after phase two and then take the high ground to the north and north-west of Potigny (Hills 183 and 195). They would then try to maintain contact with the German troops.

Since the departure of 1.SS-Panzer-Division LAH for the Mortain sector, only two German infantry divisions opposed this powerful Canadian corps, which comprised of two divisions and two armoured brigades, as well as three infantry divisions. On 5 August, the 89.Infanterie-Division arrived to relieve the LAH, and was now facing the area from La Hogue to the Orne, north-west of Saint-Martin-de-Fontenay. The 271.Infanterie-Division took up position along the eastern bank of the Orne, within the narrowing front, having relieved the Hohenstaufen. Like the 89.Infanterie-Division, its position lined up along the river, facing the eastern bank, up to 2 kilometres north of Thury-Harcourt, although the positions only really constituted a succession of support points. This area was under the control of the I.SS-Panzer-Korps and the only available reserves consisted of elements from the 12.SS-Panzer-Division Hitlerjugend, although this division was also intended to be involved in the counter-attack on Mortain. This meant that the 89.Infanterie-Division would be on its own, with no panzers, against the Canadian Corps’ offensive . For now, these elements from the Hitlerjugend were using panzers from the Kampfgruppe Wünsche, which included the schwere SS-Panzer-Abteilung 101 and its powerful Tiger tanks.

The Grimbosq Bridgehead

As discussed above, the operation would be preceded by establishing a bridgehead to the rear of the German front, and would be launched from the west bank of the Orne. This possibility was afforded to the Allies thanks to the withdrawal of the Panzerarmee to the west of the Orne and the abandonment of Hill 112 in order to shrink the front and reserve forces. Thus, two divisions from XII Corps, the 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division and the 59th Infantry Division, which had followed the retreating German infantry divisions, were able to seize the bridges in the Evrecy and Avenay sectors. These two divisions were then ordered to build bridgeheads east of the Orne. The operation would take place in four phases:

First phase – The 59th Infantry Division would establish a bridgehead on the Orne, near Brieux, 5.5 kilometres north of Thury-Harcourt, with tank support provided by the 107th Battalion Royal Armoured Corps.

Second phase – The 53rd Infantry Division would then take over the bridgehead.

Third phase – The 59th Infantry Division would then establish a bridgehead near Thury-Harcourt, take Hill 205, 1 kilometre west of Meslay, and Hill 192, to the south-east of the former.

Forth phase – If the 59th Infantry Division were able to advance from the bridgehead established near Thury-Harcourt, the 53rd Infantry Division would cross it and push on to Falaise. If Hills 205 and 192 were not taken by the 59th Infantry Division, the 53rd Infantry Division would take them instead, before continuing to Falaise.

At 18:40 on 6 August, the British soldiers from XII Corps released artificial smoke in the Thury-Harcourt and Grimbosq sectors. During the night of 6-7 August, the artillery sent a rain of fire down on the German sector for two hours, before the 176th Infantry Brigade (59th ID) managed to cross the steep bank of the Orne, near Grimbosq, and to the south of it town, supported by the 107th RAC (tank battalion). On the afternoon of 7 August, two tank companies advanced across the river and then west of Brieux, on the eastern shore, towards Lower Grimbosq, in order to support the infantry. Meanwhile, in the morning, the battalion of fusiliers from the 271.Infanterie-Division had led a counter-attack to reduce the Grimbosq bridgehead, but was pushed back at the cost of many casualties for the Germans. The same would happen again following a second counter-attack.

The British were now firmly established on the eastern shore, supported by two tank companies, as elements from the 271.Infanterie-Division were unable to repel this already powerful force. As a result, the German commander-in-chief sent in the Kampfgruppe Wünsche in a counterattack. This particular Kampfgruppe was made up of staff from SS-Panzer-Regiment 12, the staff from the regiment’s 1st Battalion, with the 3rd Company (Panther) and 8th Company (Panzer IV), a company from schwere SS-Panzer-Abteilung 101 (Tiger), and the grenadiers of 1./26 and III./26 (minus its staff and a company).

The situation became critical during the day, and the British bridgehead strengthened from Lasseray (1 kilometre north of Grimbosq) via Grimbosq (to the east of the village) and Brieux (to the east) to the south of the locality, where the destroyed bridge over the Orne and the crossing point were located. The forward British elements had by now reached the forest of Grimbosq, as the front held by the 271.Infanterie-Division was several kilometres wide. Engaging the Kampfgruppe Wünsche now became a priority. However, during its march to the combat zone it was attacked by fifty-four bombers. Its Flak guns fired back immediately, damaging thirty-six, indeed so much so that some of the planes would not return to England.

The III./26 was sent in to clear out the Grimbosq Wood, allowing the rest of the Kampfgruppe to attack from the south and south-west of the forest. It was supported by the Hitlerjugend’s 3rd artillery group of (III./SS-AR.12). The Kampfgruppe attacked at 21:00 and made good progress, as panzers and infantry penetrated into Grimbosq and Brieux. The southern branch of the attack, with elements from the I./26, advanced to the bridge at le Bas de Grimbosq, according to the report by SS-Unterscharführer Förster, who was in position with two Russian guns (‘Ratschbumm’) from the 4./26’s tank section. However, he was forced to destroy them once all of the shells had been fired. At the end of a violent battle, twenty-eight tanks were destroyed, two of them by III./26, but the counter-attack’s initial success was soon stopped by the intervention of the British artillery. British observers could look out over the area from Hill 162, west of Goupillières, as Grimbosq is only 100-120 metres above sea level on the eastern shore. The grenadiers had to dig in and the German artillery was unable to see the Orne Valley and the crossing points. The panzers suffered under the terrible effects of the artillery, which caused the death of SS-Untersturmführer Alban, as reported by a veteran of SS-Panzer-Regiment 12’s 3.Panzer-Kompanie, SS-Sturmmann Hermann Linke, who recounted the battle near Grimbosq as the panzers were forced to retreat to more favourable positions:

It was in the late afternoon of 7 August. We were driving down a lane in the forest. Gradually, the wood thinned. But what we saw next was no longer a forest. Only tree stumps remained. All of the trees had been ripped apart by the artillery to a depth of about 200 metres. Outside of the forest was a large orchard. There too, there was not a tree that had not been shredded by artillery fire. We took up position at the edge of the wood. The Orne River flowed down in the valley, about 800 metres from us.

The attack started in the evening, together with the infantry. As the panzers’ engines were starting up, the enemy artillery fire resumed. The barrages were getting louder and stronger, and soon we could no longer see the grenadiers. Suddenly, the panzer on our left took a hit and caught fire immediately. On our right was SS-Untersturmführer Alban’s panzer. My commander, SS-Oberscharführer Mende suddenly said, ‘Alban has left his panzer and is leaping from one panzer to another. He must be crazy to leave his vehicle during this artillery barrage’. Alban shouted, ‘Disengage!’ He probably did not want to transmit this order by radio.

Then there was a terrible bang. A shell exploded right beside our panzer and we all immediately thought of SS-Untersturmführer Alban. Mende said to the driver, ‘Drive back slowly, maybe we can give Alban some cover that way.’ But we could not see him, and so Mende then gave the order to move forward again, hoping to catch sight of Alban. That’s when we saw him. He was leaning against a tree trunk, dead. I had never been a hero, but now I had to get out. I jumped towards the dead body of my platoon commander and secured his pay-book and other papers he had with him.

The enemy had observed our movements and concentrated his fire on us. The fire was so heavy that we were unable to take the body of our commander with us. In order not to get knocked out ourselves, we had to pull out as quickly as possible. By carrying the order to disengage in person, Alban had probably saved all of our lives and sacrificed his own. He was a brave soldier and a shining example for his men.

SS-Unterscharführer Heinz Freiberg was another veteran from the Panzer-Regiment. He reports that another platoon commander from 3./12 (Panther), SS-Untersturmführer Bogensperger was killed not too far away. Under such conditions, the German Command decided to continue the attack the next day in order to destroy the bridgehead. However, during the night, the British reorganised themselves so that they would be able to hold the bridgehead whatever happened. As a result, the new German counter-attack on 8 August would also fail. The fighting around Grimbosq resulted in a total loss of 122 men for Kampfgruppe Wünsche, including 24 killed, 91 wounded and 7 missing. SS-Panzer-Regiment 12 would lose 3 officers (including Alban and Bogensperger), 1 non-commissioned officer and 6 men (killed), while another 6 officers and 8 men were wounded. A total of 9 Panther tanks would be lost. Casualties from I./26 included 2 sub-officers and 48 men, while III./26 lost 7 men (killed) with 3 non-commissioned officers and 17 men wounded, and 7 men missing. The III./SS-AR 12 would lose a warrant officer. For their part, the British lost 28 tanks.