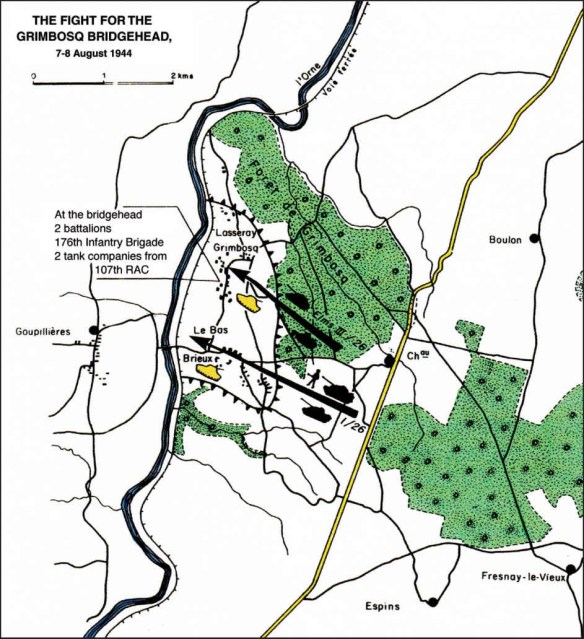

Map showing the fighting that took place for the Grimbosq Bridgehead.

The Grimbosq Bridgehead

On 6 August, 176th Brigade, 59th Division, crossed the Orne near Bas de Brieux (near Grimbosq). The 271.ID fought fiercely, but the English were able establish a bridgehead. Kampfgruppe Wünsche counter-attacked on 7 and 8 August with Panther tanks and Tigers from 2nd Company.

However, the intervention of the 271.Infanterie-Division and Kampfgruppe Wünsche at the bridgehead prevented the 89.Infanterie-Division collapsing of its left flank. Despite their bridgehead, the British would remain temporarily blocked, unable to extend it, and this decisive action remained limited within the context of Operation Totalize.

However, at the time of the fighting, at 21:40 on 7 August, Heeresgruppe B ordered the transfer of the Hitlerjugend Division to reinforce the Panzergruppe, who were fighting next to the 7th Army. The transfer operations were activated and Kampfgruppe Wünsche was to follow at 10:00 on 8 August, after the destruction of the Grimbosq bridgehead. But two hours after the order arrived, at 19:45 on 7 August, SS-Brigadeführer Kraemer told the Panzerarmee that shelling was taking place in the Bretteville-sur-Laize sector and between Boulon and Grimbosq. Meanwhile, violent Allied artillery fire was falling on the German front line, which was the sign of an imminent offensive, and Kraemer requested that the Hitlerjugend Division remained at the disposal of I.SS-Panzer-Korps. It would eventually stay in the sector and thus play an important role in Operation Totalize.

The 12.SS-Panzer-Division was no longer at full strength, having suffered casualties following two months of heavy fighting, and some of its elements had been detached to the west (Kampfgruppe Olboeter). It currently comprised of Kampfgruppe Wünsche (as we have seen), which gathered all available panzers, Panthers at the Grimbosq bridgehead;, thirty-nine Panzer IVs, and around twenty Tigers (2nd and 3rd companies of SS Panzer-Abteilung 101), three grenadier battalions (I./25, I./26, III./26) and artillery (SS-Panzer-Artillerie-Regiment 12 and SS-Werfer-Abteilung 12).

On I./SS-Panzer-Korps’ right flank, to the east, the 272.Infanterie-Division would play an intermittent role against the left flank of the Allied offensive. But overall, the balance of power was very much in II Canadian Corps’ favour, which launched 60,000 men and more than 600 tanks into battle, meaning the odds were about three to one for men, and ten to one for tanks.

The 12 Manitoba Dragoons

This was the II Canadian Corps reconnaissance group and was launched into battle on 9 August 1944. 13 August was a black day for this unit, when nine vehicles were destroyed. C Squadron was in contact with elements of the 51st Infantry Highland Division in the Saint-Sylvain area. The unit would then participate in the closing of the Falaise Pocket.

The 51st (Highland) Infantry Division

The 51st (Highland) Infantry Division saw action in the French Campaign (1939-1940), during which many of its number were taken prisoner. Reconstituted in Great Britain, it went on to serve in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and then in Sicily (1942-1943), before being repatriated to England to begin training for the Normandy Invasion. Its first elements landed on Gold Beach in the evening of 6 June, before taking part in Operation Epsom. From 7 August it was attached to the II Canadian Corps, with whom it fought during Operation Totalize.

The Canadian Corps

The 4th Canadian Armoured Division provided the other armed force of the offensive, and was part of the 1st Canadian Army and II Canadian Corps, commanded by Major General George Kitching. It was created in Canada in 1942 and transferred to Great Britain from the autumn of 1943. It landed in Normandy in the last week of July 1944, taking over from the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on the night of 30-31 July. By 2 August it was already advancing towards Tilly-la-Campagne, although it failed to capture this position, and then came to a halt at La Hogue on 5 August. However, it was now preparing for the new operation and was comprised of an armoured brigade, as well as an infantry brigade.

– Reconnaissance was provided by the 29th Reconnaissance Regiment, The South Alberta Regiment.

– The 4th Armoured Brigade aligned the 21st Armoured Regiment (The Governor General’s Foot Guards), the 22nd Armoured Regiment (The Canadian Grenadier Guards), the 28th Armoured Regiment (The British Columbia Regiment) and a motorised infantry battalion attached to The Lake Superior Regiment.

– The 10th Infantry Brigade aligned The Lincoln and Welland Regiment, The Algonquin Regiment, and The Argyll and Sutherland Regiment (Princess Louise’s).

– It also included artillery from the 15th and 23rd Field Artillery Regiments, 5th Anti-Tank Regiment and the 8th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment. In addition, engineering support was provided by the 4th Canadian Armoured Divisional Engineers and communication and information was provided by the 4th Canadian Armoured Divisional Signals.

Two Canadian infantry divisions would also join the offensive.

The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division was under the command of Major General Charles Foulkes. Born on 3 January 1903, he was a lieutenant in the Royal Canadian Regiment in 1926, made captain by 1930, lieutenant colonel in 1940, brigadier in September 1942, then finally major general in 1944, when he took command of division on 11 January.

– Its 1st Infantry Brigade (4th Brigade), aligned The Royal Regiment of Canada, The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry and The Essex Scottish Regiment.

– Its 2nd Infantry Brigade (5th Brigade) aligned The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, Le Régiment de Maisonneuve and The Calgary Highlanders.

– Its 3rd Infantry Brigade (6th Brigade) aligned Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada and The South Saskatchewan Regiment.

Reconnaissance was provided by the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars) and artillery was provided by the 4th, 5th and 6th Field Artillery Regiments, the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, the 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, the Toronto Scottish Regiment (machine guns and mortars), the 2nd Canadian Divisional Engineers and the 2nd Canadian Divisional Signals.

The division was formed at Aldershot in 1940 and participated in the landing attempt at Dieppe in August 1942. It landed in Normandy in the first week of July 1944, attached to the II Canadian Corps with the 51st ID, and took part in Operation Atlantic from 18 July onwards. It then unsuccessfully attacked the Verrieres ridge on 20 and 21 July, before taking part in Operation Spring from the 25th. The Black Watch had lost 324 men after finally taking Verrieres, but now remained stuck at May-sur-Orne, Saint-André-sur-Orne and Saint-Martin-de-Fontenay. However, all this meant that the men knew the area well.

The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, commanded by Major General R.F.L. Keller, had been fighting in the Battle of Normandy since 6 June 1944. It was formed on 20 May 1940 and was chosen in July 1943 as the first Canadian division to land in Normandy. It fought bravely in the fighting to the west of Caen against the Hitlerjugend, and was the first to enter the city on 9 July. It was attached to the II Canadian Corp as of 11 July, along with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. It proceeded to participate in Operation Atlantic on the 18th and Operation Spring on the 25th, before finally being relieved by the 4th Canadian Armoured Division on the night of 30-31 July and being sent to the rear to recuperate. On 7 July it was recalled in order to participate in Operation Totalize and would be in action on the night of 9-10 July.

– Its 7th Brigade comprised of The Royal Winnipeg Rifle Regiment (The Winnipegs), The Regina Rifle Regiment (the Reginas) and the 1st Battalion The Canadian Scottish Regiment.

– Its 8th Brigade comprised of The Queen’s Own Rifle of Canada, Le Régiment de la Chaudière and The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment.

– Its 9th Brigade comprised of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada (HLI), The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (Glens or SDG) and The North Nova Scotia Highlanders (Novas or NNSH).

Reconnaissance was provided by the 7th Reconnaissance Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars) and artillery by the 12th, 13th and 14th Régiments, the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment and the 4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment.

The Canadian Corps also included the 51st (Highland) Division, a British unit, which was commanded by Major General Tom Gordon Rennie. He had been injured on 12 June while in charge of the 3rd Infantry Division, and then took over command of 51st Division on 26 July following the dismissal of Major General C. Bullen Smith. The division comprised of three battalions of the Black Watch, a regiment that had first been created in 1740.

– Its 152nd Brigade comprised of the 2nd and 5th Battalions The Seaforth Highlanders, and the 5th Battalion The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders.

– Its 153rd Brigade aligned the 5th Battalion The Black Watch, and the 1st and 5th/7th Battalions The Gordon Highlanders.

– Finally, its 154th Brigade was made up of the 1st and 7th Battalions The Black Watch, and the 7th Battalion The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

The German forces opposing the offensive

The 89.Infantrerie-Division would bear the bulk of the offensive. The unit had been formed in January 1944 in Bergen near Celle, in northern Germany, as a division of the 25th wave, and trained in Norway from March to June. It was commanded (from February to September 1944) by Generalleutnant Conrad Oskar Heinrichs. In June, it was ordered to join the western front and four trains arrived at Le Havre and in the Amiens sector on 26 June, although by this time the rest of the trains carrying the men had not yet reached the OB West. Like the 84.ID and 85.ID (which would also see combat in Normandy), the division was low on numbers, with only 8,000-8,500 men. In fact, it comprised of only two infantry regiments; the Grenadier-Regiment 1058 and the Grenadier-Regiment 1056. Its artillery regiment (189) comprised of three groups and it also had an anti-tank group (Panzerjäger-Abteilung 189) with a single battery, and a battalion of fusiliers, the Füsilier-Battalion 189. On 3 August, it was placed under the authority of I.SS-Panzer-Korps and the next day its units were approaching the front. The Grenadier-Regiment 1056 was already in the Falaise/Bretteville-sur-Laize area, along with III./Artillerie-Regiment 189 and Panzerjäger-Abteilung 189. The Füsilier-Bataillon 189 and II./Artillerie-Regiment 189 were near Thiberville, while I./Artillerie-Regiment 189 was still south of Lisieux (according to OB West I Nr. 6450/44 g.Kdos, 4.8.44, T311, R28, F7035148). The division was in line by 6 August, reinforced by 13 Sturmpanzer IVs, which had been provisionally detached from Sturmpanzer-Abteilung 217 (from OB West Ia Nr. 6526/44 g Kdos 6.8.44, TR 311, R28, F7035220 and Pz.Gr.West Ia Nr. 801/44, g.Kdos, 7.8.44, Nachtrag zur Tagesmeldung 6.8, T313, R420, F8714118).

On the left flank was the 271.Infanterie-Division, which had been formed in November 1943 in the centre of Germany, from the former staff of the 137.ID and a large number of soldiers from this division, which had been dissolved after two years of fighting on the Eastern front. It took the number of an old 271.ID, which had been formed at the beginning of the summer of 1940 in Wehrkreis (military region) V and was made up of elderly soldiers who were to be sent to France in case the country continued to resist. As the campaign in France only lasted six weeks, the division was dissolved and its number was reassigned to a new division formed in Wehrkreis XIII. It completed its training in Holland and then joined the Montpellier sector, in the South of France. It quickly reached full strength, having just 119 men on 1 April 1944, but 11,617 men plus 1,004 Hiwis (volunteers from the USSR) by 19 June. It had 330 machine guns and 72 sub-machine guns, 58 8 cm mortars, 19 7.5 cm infantry guns, 6 15 cm heavy infantry guns, 32 10.5 cm howitzers, 22 7.5 cm Pak guns, 188 motorcycles, 158 light vehicles, 164 trucks, 38 self-propelled vehicles and 4,484 horses! It comprised of three infantry regiments; the GR 977, 978 and 979. The Artillery-Regiment 271 (four groups) had 3-4 guns for the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th, 9th, 10th and 11th batteries. The 12th had 3 guns, the others 4 (Anlagen zum KTB Nr.2 LVIII, Pz.Korps Ia, Gliederung 271. New Div.I.7.44, T314, R1496, F000963). The Panzerjäger-Abteilung 271 was a single company (Panzerjäger-Kompanie). The division was sent to the Normandy front at the end of June, embarking from Lyon on 1 July. It headed first for Rouen, because at the time, the plan was to send it to the Pas-de-Calais. Then, on the night of 13-14 July, its first elements (II./GR 979 and Panzer-Kompanie) arrived in the area north of Thury-Harcourt. On 15 July, 47 trains were scheduled to leave and 23 of them arrived with men. Three days later, the following elements arrived: II./GR.978, 3., 8. and 9./AR 271 at Livarot, II./AR 271, 13e and 14./GR 979 at Falaise, the Pionier-Bataillon 271, III./AR 271 (partially) were at Bernay, the 1st and 2nd batteries of AR 271 were at Brionne, most of the IV./AR 271 was at Chartres, I./GR 978 and the 7th battery of AR 271 were in Houdan, while the I./GR 971 was in Rouen. On 23 July, the bulk of the division took over from the 10.SS-Panzer-Division Frundsberg in the sector of Hill 112, west of the Orne. The other elements arrived the following day, but part of the units were still in the Livarot/Saint-Pierre-sur-Dive/Mézidon sector. Then, during the retreat to shorten the front line, the 271.ID moved to hold the eastern bank of the Orne between the left flank of the 89.ID and Thury-Harcourt, relieving the 9.SS-Panzer-Division. This was its position on the eve of Operation Totalize. From December 1943 to October 1944, the division was commanded by Generallutnant Paul Danhauser.

Sturmpanzer IV ‘Brumbär’ (sd.Kfz. 166)

Sturmpanzer-Abteilung 217 was the only unit to have been equipped with Sturmpanzer IVs during the Battle of Normandy, and had short 15 cm howitzers mounted on an armoured cockpit on a Panzer IV chassis. Although the gun’s low speed made it ineffective against tanks, it was otherwise useful against fixed targets. The battalion comprised of three companies of fourteen vehicles each and three others for the command company. Its organisation was similar to that of Sturmpanzer-Abteilung 216, which saw action at the Battle of Kursk. This unit was first stationed in the Reich (at Grafenwöhr), and on 24 June 1944 received orders to join the Normandy front, reaching the area around Condé-sur-Noireau/Le Bény-Bocage and Vire on 18 July. However, it did not appear to have all of its allocated panzers and it would only be used sparingly. On 21 July, its 2nd Company was in the 21.Panzer-Division’s sector and was attached to the division two days later. On 24 July it comprised of eleven Sturmpanzer IVs, with two in repair. On 29 July it was attached to the 1.SS-Panzer-Division LAH. The next day, it lined up nine panzers, with two in repair. On 30 July, 3rd Company was transferred from the II.SS-Panzer-Korps to the LXXIV Korps. On 6 August, thirten Sturmpanzer IVs from this battalion were with the 89.Infanterie-Division (Pz.Gr.West Ia Nr. 853/44 g. Kdos, 10.8.44, Nachtragzur Tagesmeldung 9.8., T313, R420, F87141177). On 9 August, ten of these panzers were in action with the Hitlerjugend and only one with the 89.ID. On the 10th, only five were operational with the HJ, and the situation was the same the following day. On 11 August, 1st Company was attached to the 271.Infanterie-Division (Pz AOK 5 Ia Nr 899 /44g. Kdos, 12.8.44, Nachtrag zur Tagesmeldung 11.8., T313, R420, F87141187). According to a report of 16 August, the battalion’s losses from 1-15 August were ten killed, thirty-five wounded and twelve missing. Out of 772 men, 69 were missing. A total of seventeen Sturmpanzer IVs were combat ready, but fourteen were under repair (predicted to be ready in less than three weeks). The battalion’s tanks would see action equally between the 89.ID and the HJ, as the two units fought side by side.

An anti-aircraft Crusader III AA MK3 TANK from the 1st Polish Armoured Regiment. Note the letters ‘PL’ for Poland and the number 51 for the unit.

The 1st Polish Armoured Division

The 1st Polish Armoured Division was commanded by Major General Stanislaw Maczek, who had been a colonel in the 10th (Motorised) Cavalry Brigade in Poland as early as October 1937 (the brigade had been formed in the spring of 1937). After fighting in Poland, the brigade retreated to Hungary and the men headed for France at the end of October 1939. Following the defeat of France, many of its members made their way to Britain, where the idea of reconstituting a Polish armoured unit quickly re-emerged, thanks to the efforts of General Sikorski. The remnants of the 10th Brigade settled in Scotland, establishing its headquarters at Forfar. Due to their travels throughout Europe, German propaganda described the brigade’s men on the radio as ‘General Sikorski’s tourists’. However, they would eventually prove to be very formidable opponents and the decision to regroup them in an English armoured division, the 1st Polish Armoured Division, was taken on 25 February 1942 on the orders of General Sikorski.

Even after intensive training, its numbers were still inadequate as there were too many older soldiers. The division was inspected by Marshal Montgomery on 13 March 1944 and a month later, on 13 April, General Eisenhower’s inspection prompted more sympathy among the Poles. By the time of Operation Overlord, the division comprised of 885 officers, and 15,210 non-commissioned officers and men. Its resources included a reconnaissance unit, an armoured brigade, a detached infantry brigade, divisional artillery, and engineering and service units, just as any other British division.

– Reconnaissance was provided by the 10th Polish Mounted Rifles, equipped with Cromwell tanks and commanded by Major Maciejewski.

– The 10th Polish Armoured (Cavalry) Brigade was commanded by Colonel T. Majewski, with Major Marian Czarnecki as his Chief of Staff. It was known as the ‘Schwarze Brigade’ (Black Brigade) by the Germans, in reference to the colour of the uniforms worn by the tank crews. The men also wore black berets, unlike their British counterparts, who wore khaki ones. The brigade, commanded by Colonel Wladislawdec, was equipped with Sherman tanks and included the 1st Polish Armoured Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Stefanewicz (its regimental insignia bore the coat of arms of Saint-Nicholas); the 2nd Polish Armoured Regiment; the 24th Polish Lancers Regiment and the 10th Polish Dragoons Regiment.

– The 3rd Polish Infantry Brigade, or 3rd Rifle Brigade, included the 1st Polish (Highland) Battalion; the 8th Polish Battalion (or 8th Rifle Battalion); the 9th Polish Battalion (or 9th Rifle Battalion), which was known as Flanders, and the 1st Polish Independent HMG Squadron.

– The division’s artillery was provided by the 1st Polish Motorised Artillery Regiment; the 2nd Polish Motorised Artillery Regiment; the 1st Polish Anti-Tank Regiment, and the 1st Polish Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment.

– Other units included the Engineers (10th and 11th sappers), as well as medical services, military courts, reserve squadrons etc.

The 1st Polish Armoured Division joined the front only shortly before Operation Totalize, on 30 July 1944. Edward Podyma was originally from Poland, but had been living in Normandy, near Potigny, where a large Polish community had settled in the area in the 1920s, due to the iron mines:

How did I find myself in this war? I received mobilization orders from the Polish Army (in France) on 11 June 1940, more than two months before my eighteenth birthday. I first had to go to a recruiting centre in Coëtquidan, 45 kilometres south-west of Rennes. In June 1940, the situation escalated quickly and there was no alternative but to defend our cause. Those who choose to continue the struggle headed for England. After four years of training in Scotland we were eager to see some action, but we didn’t land on the Normandy coast until 30 July 1944, at Courseulles-sur-Mer.

Other units, especially the armoured ones, disembarked at Arromanches. The division gathered to the south of Bayeux before finally setting out for the front on 6 August. Besides Corporal Podyma, other Poles from the Potigny area included Michal Kuc, who had arrived in Normandy in 1924 and worked as a miner in Saint-Rémy-sur-Orne. He was now the driver for the brigade commander, Major Wladislawdec’s tank. Meanwhile, Stephan Barylak, who had arrived in France at the age of seven, had also been signed up in Coetquidan before travelling to England. In April 1942 he was incorporated into the 24th Lancers. All three men worried about their families, and whether or not they would encounter them during this offensive, especially when destiny saw fit to bring them so close to the Polish colony of Potigny.