The fighting that ended in 1949 erased Palestine from the map and destroyed Palestinian society. Over 700,000 Palestinians became refugees. Barred from returning to their villages, most of which were soon bulldozed by Israel, Palestinian refugees were dispersed among surrounding Arab countries, with a high proportion going to the West Bank and Gaza. However, new form was given to Palestinian nationalist identity by their common insistence on their right to return. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) played an important role in providing services, especially in education. Set up in 1949 to provide relief services, UNRWA gradually took on more responsibility in the fields of education and health. But the fact that the refugees’ livelihood was basically dependent upon the goodwill of distinct host states resulted also in Palestinian political and social fragmentation. For example, in Lebanon—where some 150,000 Palestinian refugees threatened to upset the delicate population balance on which the governmental system of proportional communal representation was based—more Palestinian Christians were absorbed into Lebanese society than Palestinian Muslims. Proportionately, the Gaza Strip admitted the largest number of refugees: its 80,000 inhabitants, who in 1948 came under Egypt’s military administration, absorbed 200,000 refugees. Only Jordan conferred citizenship upon the refugees: for King Abdullah, gaining control over the important Muslim shrines of Jerusalem’s Old City and bolstering his regional importance fully justified the annexation of the newly carved-out West Bank, refugee camps and all. West Bank resources and manpower tended to promote the development of the East Bank.

In 1964, the creation of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) gave Palestinians a new focus of political identity. Its charter called for a Palestinian Arab state on all the whole of mandate Palestine, describing it as an ‘indivisible territorial unit’ and declaring the establishment of Israel ‘illegal and null and void’. When the PLO was formed at the first Arab summit, many prominent Palestinians participated but they became highly suspicious of the organization’s evident subordination to Egyptian President Nasser. The organization’s effectiveness as a national institution was further curtailed by the opposition of Jordan’s King Husayn, who viewed it as a threat to his claim of sovereignty over the West Bank and its inhabitants. Meanwhile, other Palestinian groups were also organizing themselves with the aim of taking control of their own struggle against Israel. The most important of these groups was Fatah (Arabic for ‘conquest’), founded in Kuwait in 1959 and led by Yasir Arafat.

Arafat’s ability to move the PLO beyond the tutelage of Arab states and take control of the organization as a whole came as a direct result of their defeat in June 1967. The war seriously weakened the hold of Arab states on Palestinian activity, and hurt the legitimacy of the previous PLO leadership. In March 1968, Fatah launched guerrilla operations against the West Bank from bases in Jordanian villages. After an Israeli reprisal attack on the village of Karamah met fierce resistance by the guerrillas, who were supported by the Jordanian army, the battle of Karamah (the name means ‘honour’ or ‘dignity’ in Arabic) became a symbol of heroic resistance. Fatah’s popularity then soared, inspiring a rapid influx of volunteers, donations, and armaments. Wearing his black-and-white chequered keffiyeh (head cloth), Arafat became the public face of the Palestinian guerrilla movement. In 1969 he was elected chairman of the PLO (a position he held until his death in 2004). In 1974, at the Arab summit held in Rabat, the PLO received recognition as the sole representative of the Palestinians. And later that year, Arafat addressed the UN general assembly and the PLO was granted observer status.

Adopting the tone of contemporary radical anti-colonial movements, the 1968 Palestine Charter placed special emphasis on armed struggle as a strategy and not just a tactic and thus as the only way to bring about the liberation of Palestine. It rejected Zionism’s claims on any part of Palestine, acknowledging Judaism only as a religion, not a nationality. The organization’s embrace of armed struggle contributed to mobilizing Palestinians and attracted international attention to their plight. But the PLO was an umbrella organization and Fatah’s role, though dominant, was not uncontested. Given Palestinian dispersal, Arafat preferred to try to bring all factions, some of which had very different agendas, under a big tent rather than place a premium on discipline and obedience. His persistent failure to oppose the more violent approaches embraced by smaller militant groups (such as the terrorist operation against Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972 and the 1985 hijacking of an Italian passenger ship, the Achille Lauro, during which a Jewish American tourist was murdered) tended to undermine the legitimacy of the Palestinian movement and solidify the image of Palestinians as terrorists on the world stage. It also brought the organization into conflict with neighbouring host countries such as Jordan and Lebanon. The relationship between Arab governments and Palestinian nationalism was an ever-shifting one: generally, the regimes’ rhetoric espousing the liberation of Palestine was backed up by limited support or a desire to control the movement for their own purposes.

In particular, the relationship between the PLO and Jordan, where Palestinians established bases from which to organize guerrilla armed struggle against Israel, was volatile from the outset. It ended in disaster in 1970 when the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a component of the PLO which was determined to overthrow the Hashemite monarchy, staged multiple hijackings of international airline flights. King Husayn declared war on the PLO after accusing it of creating ‘a state within a state’, and killed 3,000 Palestinians in the process. Expelled from Jordan, most PLO guerrillas regrouped in Lebanon, where Arafat soon established a number of social and economic organizations and indeed relocated the entire PLO infrastructure there.

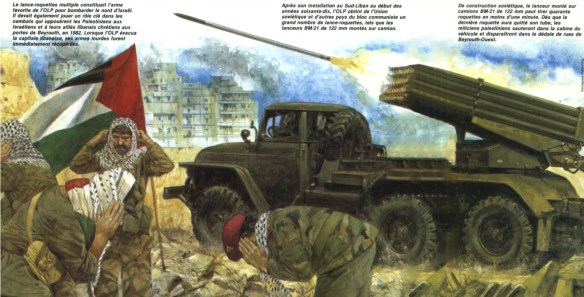

But its presence in Lebanon increasingly threatened the country’s delicate political and demographic balance. When civil war broke out in 1975, Lebanon’s Christian leaders were particularly concerned about the challenge the Palestinian ‘state within a state’ posed to their political dominance. They sought help from Israeli leaders who were equally concerned about the presence of PLO guerrillas on their northern border. In 1982, an assassination attempt on Israel’s ambassador to the United Kingdom provided the Israeli government with a pretext to invade Lebanon and expel the PLO from its power base in Beirut. In June, Israeli troops pushed up the coastline. They moved deep into Lebanon, occupying the south and then laying siege to the capital. As Beirut came under heavy bombardment, the PLO faced pressure from most Lebanese political parties to leave. In August thousands of Palestinian fighters were forced to evacuate, and the PLO leadership along with many fighters withdrew to Tunisia, Syria, and further afield. The following month, Lebanese Christian militiamen entered the now unarmed Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila and, with the help of the protective presence and night-time flares provided by the surrounding Israeli army, slaughtered thousands, including women and children.

The costs of the war for Lebanon were staggering, and the regional repercussions of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon were also profound. Politically, an important new force emerged in south Lebanon. The predominantly Shi’ite Muslim community had initially welcomed an end to PLO armed operations, which had made the area a dangerous place in which to live. But Shi’ite resentment of Israel intensified as an Israeli occupation in the south took root. Israel had hoped that the expansion of a ‘security zone’ stretching 5 to 25 kilometres inside Lebanon would offer Israel a protective buffer. Instead, it quickly replaced one foe with another. On Israel’s northern frontier, the fight against occupation was now led by the newly established Shi’ite militias Amal and, later, Hizbullah (Party of God). In the struggle for control over their land, Amal and Hizbullah launched violent guerrilla campaigns assisted by Syria and Iran. Israel finally withdrew fifteen years later.

Reverberations of the Lebanon war were also strongly felt in Israel’s domestic politics. The invasion left Israelis deeply divided. As news of the atrocities dominated the headlines, protests against Israel’s role in the Lebanon war mounted, and Prime Minister Menachem Begin faced increasing pressure to form a commission of inquiry to investigate the Sabra and Shatila massacre. The commission called for the dismissal of Defence Minister Ariel Sharon, while public pressure increased on Begin to resign, which he did the following year.

For Palestinians, the fallout from the Lebanon war was also profound. In exile in Tunisia, the PLO leadership now looked out upon a very different political landscape. With very little to show for eighteen years of armed struggle, the focus gradually shifted to the pursuit of diplomatic initiatives. A new strategy developed, involving recognition of the existence of the Israeli state and envisaging a redefinition of a state of Palestine based on the West Bank and Gaza, and not on the whole of the post-First World War mandate territory. However, shifts in international relations at this time, in particular the end of the Cold War, threatened to lessen dramatically the PLO’s significance as well as its cause. Confined to Tunis, the PLO’s central leadership drifted, until thrown a lifeline by the 1987 uprising against the Israeli occupation, known as the intifada.

Following the failure of diplomatic efforts in the wake of the 1982 Lebanon war, the 1987 Palestinian intifada (which means ‘shaking off’ in Arabic) carried the conflict back into the spotlight of the international arena. Television images of Palestinian youths armed with slingshots facing off against Israeli tanks upended common international perceptions of a David and Goliath conflict. The intifada also fundamentally transformed political equations on the ground. More than a venting of anger at the Israeli occupation, the intifada was a powerful expression of the depth of Palestinian nationalism.

As the intifada gathered steam in the late 1980s, the PLO and the Israeli government were both forced to devise appropriate responses. Both had been taken by surprise by the scope and nature of the intifada. The intifada forced and empowered the Arafat leadership in Tunis to develop new diplomatic strategies based on a two-state solution. Eager to capitalize on the political momentum to gain international legitimacy, the PLO in 1988 accepted Resolution 242 and recognized Israel’s right to exist. Israel too was forced to respond to the transformed landscape. Searching for ways to disengage from the direct violence of the intifada, which was increasingly spearheaded by the militant religious group, Hamas, Israel initiated direct talks in 1993 with PLO leaders. After reaching an agreement in secret talks in Oslo, Norway, Israeli and Palestinian dignitaries were invited by US President Bill Clinton to sign the new accords on the White House Lawn. At the time, the event was considered a groundbreaking moment.

PLO leaders living in exile in Tunisia worried about becoming increasingly marginalized. Inside the West Bank and Gaza, the protests comprised all strata of Palestinian society and gave birth to a new, young, and clandestine leadership known as the Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU). Though composed of representatives of the main PLO factions, this local leadership encouraged grass-roots initiatives aimed at making the occupation an immoral and unaffordable burden on Israeli society. Popular committees were mobilized to coordinate acts of civil disobedience, including the boycotting of Israeli goods and services and replacing them with those produced through local networks, and to organize daily life with the eventual aim of achieving self-determination. With the political initiative lying firmly in the hands of Palestinian leaders inside the occupied territories, a certain tension emerged between the local leadership and the outside PLO. But the successful coordination of the political goals of the UNLU with those of the PLO provided salvation to its chairman, Yasir Arafat, and his fellow Fatah colleagues. Further validation of Arafat’s role came in July 1988 when King Husayn dropped Jordan’s claims to the West Bank.

However, the intifada also gave birth to a religious resistance movement that outright challenged the PLO’s authority. Best known by the acronym Hamas (Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya, or Islamic Resistance Movement), which means ‘zeal’ in Arabic, this movement was an offshoot of the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. The Muslim Brotherhood had long been involved in religious missionary activities. When the intifada erupted, younger, university-educated leaders in the movement feared that it would lose support if it did not get involved politically. Initially encouraged by the Israeli government as a counterweight to the PLO, Hamas built on its long record of providing social services in the occupied territories and gained widespread popularity during the intifada. It vehemently opposed the PLO’s willingness to compromise on the partition of historic Palestine. Hamas’s platform sacralized the whole of what had been mandate Palestine, calling for the destruction of Israel and the establishment of a ‘state of Islam’. Crude and simplistic as its initial charter was, the movement’s popularity, and its ability to mobilize an effective network of institutions, posed a real challenge to Fatah’s authority.

For Israel, the impact of this rapidly changing political landscape was profound. Israel’s eventual success in arresting many of the UNLU leaders led to the gradual disintegration of the grass-roots networks, but not before their civil disobedience campaigns had effectively convinced many Israelis that the occupied territories could no longer be considered a secure economic or even defensive asset. The Israeli state’s initial decision to use the brutal force of an ‘iron fist’ to crush the intifada had only fuelled further rebellion while tarnishing the state’s reputation abroad as well as at home. Israelis became convinced that the status quo was both morally and practically untenable, and increasing numbers began to pressure their government to extricate itself from the occupied territories.

A further push towards some kind of political reconciliation was spurred on by Iraq’s 1990 invasion and occupation of Kuwait. US forces, supported by a multilateral coalition that included many Arab countries, had little difficulty dislodging Iraq’s forces from Kuwait. During the war itself, however, Iraq launched scud missiles against Israeli cities, hoping to break up the coalition. These missiles, which Israel feared were equipped with chemical warheads, exposed Israelis to new threats and vulnerabilities, against which control over the West Bank and Gaza offered little defence. Furthermore, the war against Iraq’s occupation of Kuwait generated growing calls that the United States also bring an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestinians. Indeed, following its 1991 victory in the Gulf War, the United States moved quickly to convene an international peace conference in Madrid in which all the states of the region participated (without the PLO). The Gulf War had in fact greatly weakened the position of the PLO. Arafat’s decision to side with Iraq dictator Saddam Husayn left him isolated diplomatically and financially cut off from further contributions from oil-rich Gulf countries: the PLO lost subsidies that it had previously received from the Kuwaiti and Saudi governments, and over 300,000 Palestinians resident in Kuwait lost their homes and their livelihoods. Israel effectively barred PLO officials from attending the Madrid conference but negotiators from the West Bank and Gaza nonetheless participated under the PLO’s authority. They gave by far the most eloquent speeches. Not only were Palestinian demands framed in reasonable terms, they were presented face to face to Israeli leaders for the first time. The Madrid talks otherwise achieved little of substance beyond securing a commitment from all parties to support an ongoing framework of bilateral negotiations. With the exception of the Israel–Jordan talks, which led successfully in 1994 to a peace treaty, the bilateral negotiations soon became stalemated. In these post-Madrid meetings, the main sticking point was Israeli settlement policies. The Palestinian delegation led by the ‘insiders’—leaders who lived and worked in the occupied territories—insisted on a settlement freeze.

The intifada’s operations against the Israeli occupation continued after Madrid. Yet they seemed to become more fragmented, more militarized, and increasingly overshadowed by internecine fighting. Then suddenly, in late August 1993, it was disclosed that a small team of individuals representing the PLO and the Israeli government had reached an agreement, while meeting in complete secrecy in Oslo, Norway. The whole world—including Palestinian and Israeli delegates in Washington who were gearing up for yet another round of Madrid talks—was astonished.