On June 12, Ottoman soldiers managed to grab a prisoner, who gave them the encouraging news that a cannonball had destroyed the bakers’ oven inside Fort St. Elmo, forcing the defenders to rely on Fort St. Angelo for bread. This intelligence was improved upon by a Spanish deserter, a piper, who informed Mustapha that, given the fort’s architecture, they needed to raise the ravelin just a little bit more to have total command of its interior piazza. Mustapha thanked the piper but, having been deceived before, assured him that if his report proved untrue, the man could expect the same bastinado treatment that had been meted out to La Rivière. While sappers redoubled their efforts on the ravelin, the piper had time to consider the various fates that threatened him. Should Mustapha be dissatisfied with the ravelin, the Ottoman camp might not be the best place for him; returning to St. Elmo, however, was out of the question. He slipped off again, this time to Mdina, where he presented himself as an escaped slave. Alas for him, he was recognized, and so, after some time on the rack, was the lie. Governor Mesquita turned him over to the citizens, who tied him to a horse’s tail and then stoned him to death.

Perhaps the sudden disappearance of the piper caused Mustapha to try to reason with his enemy. On June 14, a trumpet sounded, a white flag went up, and a herald trotted over from the Ottoman lines and offered parley, an offer the defenders refused. The herald withdrew. A little later, the defenders heard an Italian voice call out from the trenches, informing them that Mustapha would graciously allow the Christians to sleep that night and that anyone inside the fort was free to leave in peace. If they continued to resist, however, the Ottoman soldiers would cut them to pieces. In response, the Christians let loose a volley in the Italian’s general direction, which ended any further talk of surrender.

There followed a day and a night of sporadic raids, cannon volleys, the sound of shouts and music that sometimes preceded attacks, but often did not. Mustapha’s technique was that of a picador at a bullfight: the administration of modest irritants to keep the defenders off balance, sleep deprived, and confused. There was little the commanders at St. Elmo could do other than petition Valette for more men, more ammunition, and more supplies. He complied and loaded the night boats with the fire hoops and powder and biscuits and ammunition needed to defend the fort. That these small convoys were able to make their nightly runs was a significant failure on the part of the Ottomans, and lack of moonlight notwithstanding, we can only conjecture why they were allowed to proceed. Once arrived, these goods were shifted to points where the fighting, once it came, would be fiercest.

The real attack came on June 16. Two hours before sunrise, the defenders of St. Elmo could hear the Ottoman mullahs addressing the gathered Muslim force and the full chorus of the soldiers’ response. The pattern of call and response, measured by the slowly rising light to the east, seemed interminable, but the meaning was clear—the soldiers were cleansing themselves of sin and preparing themselves for death. Then silence, as the four thousand men carrying arquebuses padded to their stations. Having called up the dawn, the Ottomans ringed the fort at the counterscarp, west, southwest, and south, facing into the rising sun that at dawn would silhouette anyone who looked over the walls. They were also girding themselves mentally for the fight. They knew how tough the Christians were.

Defenders lined the cracked rim of the fort in a regular pattern—three soldiers, then a knight, three more soldiers, another knight, and so forth. Monserrat, Miranda, and d’Eguaras commanded three bodies of reserves, stationed in the piazza and ready for deployment wherever the enemy threat proved greatest. Support staff prepared wine-soaked bread to refresh the hungry and thirsty—and to comfort the wounded and dying. Guns, pikes, swords, grenades, and stones all lay within easy reach of the men on the front. Fra Roberto da Eboli had returned to the fort and was in his element: “If God is with us, who will be against us? . . . recall the ancient kings of Israel, Joshua, Gideon, Samson, Jefte, Delbora, Jehosaphat, Ezekiel, the brothers Maccabee whose zeal and valor you, sacred knights, must now emulate. . . . In this most sacred sign of the cross we shall prevail.” Not far away, Mustapha reminded his own men that Muslim prisoners inside the dungeons of Fort St. Angelo were counting on them: “Perhaps you have not heard the cries and entreaties of captives from that fortress, people joined to you by blood and bound by hardest chains, enduring a life sadder than death itself, immersed as they are in squalor and sorrow?”

Then the artillery barrage began. This time Piali Pasha had brought gun-mounted galleys to fire in concert with the land batteries. Cannon fired from the ravelin, from all platforms, and from ships offshore, throwing “around a thousand shots with such force that not only the Maltese, but also the neighboring Sicilians were dumbstruck with horror.” The bombardment stopped an hour later, as suddenly as it had begun, leaving the men’s ears ringing. A few of the defenders snatched glances over the rubble to see what was coming next. The farsighted could make out Mustapha, upright, determined, the green standard fringed with horse tails significant of the rank given to him by Suleiman himself. He stepped forward the better to be seen and drew his scimitar from its scabbard. The roar of eight thousand Muslims filled the air. The assault was on.

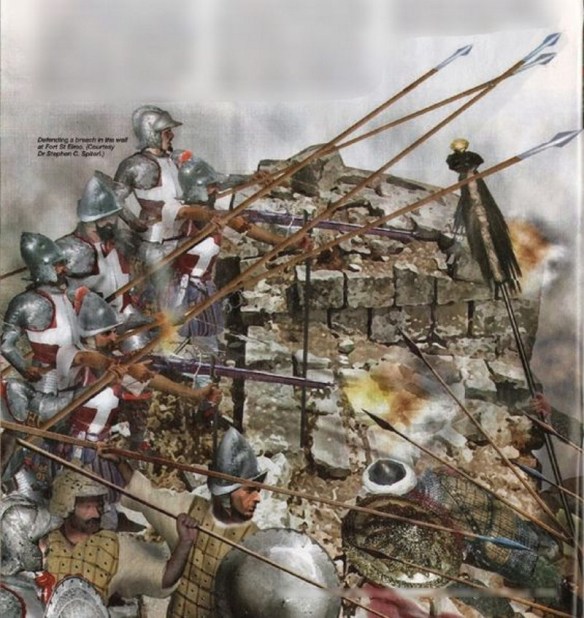

The Iayalars, religious fanatics, came first, “dressed in the skins of wild animals and the feathers of birds of prey” and with “blue tattoos of various characters on their faces.” A good number of these alarming men managed to cross the ditch and scrabble up the loose rubble toward the breach, where they were stymied by an “infinity of caltrops,” sharp spikes welded in such a fashion that one point will always face upward and impale the foot of anyone unlucky enough to walk on it. While the Iayalars contended with this new hazard, Christian arquebusiers rose up and fired into their ranks, killing many outright, wounding others, but failing to turn the tide.

Soon enough the fighting drew closer, as guns gave way to pikes and halberds, then swords, stones, and finally knives, poniards, and fists. Fortune seemed to favor the Muslims; a westerly breeze drove smoke from incendiaries into the defenders’ eyes, and more fortunate still, as the Iayalars had filled the breach, the entire store of the Christians’ firepots somehow ignited, exploded, and covered those nearby in flaming pitch. Christians and Muslims alike screamed, ran, rolled on the ground, and threw themselves into the water barrels or the sea.

Their bravery notwithstanding, the Iayalars, exhausted, withdrew soon after this incident. Mustapha now sent in his dervishes. This new strain of religious fanatic made their way over the dead and dying bodies of their coreligionists and took up the fight in a dry fog of powder smoke and the increasingly scorching heat of Malta’s July sun. The Christians managed to push the enemy back down to the counterscarp and would have pushed farther if Monserrat had not ordered them to remain in the relative safety of the fort. Zeal was all well and good, but the numbers were against them, and Monserrat wanted his men to prepare for the third wave of attackers. It was the turn of the spahis. Another charge at the breach, another failure to take it. Mustapha now turned to the warhorses of his army, the Janissaries.

The Janissaries targeted the post of Colonel Mas. Valette, watching from Fort St. Angelo, saw the attackers bringing scaling ladders to the wall, and ordered his gunners to shoot them down. Precision was wanting. Their first volley landed too far to the right and killed a mixture of the enemy and eight Christians, “putting with this misstep the fort in greatest danger of being lost.” Frantic signaling had the artillerists correct the error. Their next shot was better. Twenty Turks died, but no Christians. The remaining Muslims were few enough for the men at St. Elmo to push back successfully with pikes and trumps.

The next wave included a crew heading specifically for the cavalier. Burning hoops repelled some, and a good number were seen rushing down to the water to extinguish the burning gelatin that clung to their flesh. For seven hours “spears, torches and stones flew from all sides,” until Mustapha and Turgut finally called it quits. The defenders, once they realized they had bought another day, jeered at the retreating Muslims and heard the cries taken up by their comrades across the water in Fort St. Angelo. Mustapha’s report to Suleiman was philosophical. He wrote that he had suspended operations “because all things are tied to their destiny and marks of victory are unavoidable.”

Regrettably for him, destiny in this case had decreed a thousand Turks and only a hundred and fifty Christians should lie dead on the edge of the fort. Two Muslim standards, one belonging to Turgut, the other to Mustapha Pasha, were now in Christian hands. The battle had exhausted both sides, and veterans of the fight believed that the Turks would have been able to take the fort if they had made just one more assault. Balbi writes, in a left-handed compliment, that convicts, oarsmen, and even the Maltese fought “as if [they] were [men] of superior reputation,” persona de mayor estima.

Among the dead was Medrano, having received a bullet through the head as he seized one of the Muslim standards. Miranda had led the final counterattack and was wounded (broken leg) but not, according to him at least, incapacitated; he ordered that a chair be brought up and positioned near the big guns. Let the enemy come again—the Spaniard would stay with his men. He could, he noted, fire an arquebus from a sitting position and even kill with a sword if his enemy had the nerve to approach. Other defenders, burned, cut, maimed, of lesser birth and therefore of whom less was expected, did not stay. These, along with Medrano’s body, were ferried back to Birgu; senior among them was the badly wounded Juan de La Cerda. The force was down to some three hundred men.

Outside the battle zone, the Ottomans were on the move. They had now struck camp at the village of Zeitun, their halfway point between Marsaxlokk and Mt. Sciberras, and burned the remains—they would soon be settled closer to the fighting and bring their ships into Grand Harbor. The endgame was under way. St. Elmo would be annihilated shortly.

Valette would no longer order any more men into Fort St. Elmo, though he would accept volunteers. Three hundred men of Birgu and thirty knights stepped forward and presented themselves for service across the water. They were targeted by Turgut’s sharpshooters on Tigné, whom Valette had Coppier chase away until the boats could make it across. On June 17, Valette reported these events to Don Garcia in terms meant to encourage him to get on with sending some aid. The entire Ottoman fleet, he said, had moved from Marsaxlokk at night so “we should not see his weakness” and from “fear of your fleet,” thus leaving Marsaxlokk free for any Spanish relief force. Bombardment of Fort St. Elmo had slackened, morale was high even though supplies were low, and Valette was certain that just a few more men, even just the two triremes of the Order now in Messina, would be enough to hold the fort indefinitely. “Our safety lies in your hands; after that, our hope remains in God.”

The siege was in its twenty-fourth day. The Ottomans kept up a desultory bombardment of six guns on the southern spur, but spent the better part of their day in recovering and burning their dead. As the smoke rose and then bent back and covered the island, Mustapha and his lieutenants considered why Fort St. Elmo had not yet fallen. Exasperated at the tenacity of the enemy and eager to get the operation over with, he was ready to listen to all sides. Theories were fielded, argued, weighed, and finally reduced to three. First, the Christian gun on the fort’s eastern flank was disrupting any mass attacks on the right side. It must be taken out. Second, the guns on Fort St. Angelo had found their range and were interfering with operations on the southern side of Sciberras peninsula. They must be neutralized. And finally, the steady flow of fresh troops from Fort St. Angelo kept the defensive manpower at an insuperable level.

This last point was key, and Turgut had already begun to address it. In addition to his cannons, Turgut had placed sharpshooters on the peninsula of Tigné. Men without pity, they fired on the small boats bringing the dead and wounded back to Birgu.

#

Turgut and the Ottoman high command began the morning with a tour of the various trouble spots with a view toward improving offensive capabilities. They also reconsidered the terrain. Turgut ordered that the counterscarp of the ditch facing St. Angelo be extended down to where the relief boats from Birgu entered Fort St. Elmo. The project had been more trouble than it was worth back when the siege was estimated at five days, but reality was forcing their hand. Sappers were already pushing the Turkish trenches forward, and sharpshooters should be able to fire not just on the skiffs that ferried men across the water, but at the subterranean entrance to Fort St. Elmo. Other sappers completed the curtain wall that hid the Turks from the guns of St. Angelo.

Turgut and Mustapha and their staffs, all dressed in the brightest robes possible, were inspecting the new arrangements. Balbi writes the Turgut was dissatisfied with a Turkish gunner who was aiming his cannon too high. He told the man to lower it. Still too high. He ordered him to it lower still more, but this final time the trajectory was too low, with disastrous consequences. The ball glanced against a trench and chipped off a stone that ricocheted back and hit Turgut in the temple. Turgut’s turban absorbed some of the shock, possibly preventing him from being killed outright, but the shock was severe. Blood flowed out of his mouth, perhaps even his ear and eye, and he lost the power of speech. Staff officers, appalled, quickly covered the still breathing Turgut and carried him back to Mustapha’s own tent at the Marsa, worried that news of his injury might spread and alarm the men. Ever the professional, Mustapha continued the inspection, and with his remaining staff oversaw the emplacement of four new guns aimed at the watery route to Fort St. Angelo.

#

News of Turgut’s injury marked the beginning of a small winning streak for the Christians. The day after the corsair was hit, Grugno, the knight in charge of the cavalier, was able to lay cannon fire into knots of the enemy and kill the aga (commanding officer) of Turkish ordnance. The Ottomans’ reaction to this—piercing howls of grief—encouraged Grugno to strike out at other brightly uniformed men. To do so, he had to expose himself more than was strictly prudent. A Muslim sharpshooter soon winged him, and he was sent back to the infirmary at Birgu, replaced by a Fortunio Escudero, a knight of Navarre who was even more troublesome than his predecessor. The Muslims eventually trained thirty-four guns on the cavalier, he had become such a nuisance.

There was some encouragement for the Ottomans as well. On the evening of that same day, across the waters they heard a massive explosion, the more surprising as they had not been firing in that direction. A cloud of dust and smoke hung over the area, and only later did they learn that it had been the powder mill at Fort St. Angelo. Two kantars—about a hundred kilos—of powder were lost along with ten workers. The Turks cheered the display “with their bestial voices,” which Valette answered with a volley of cannon fire across the waters. Fra Sir Oliver Starkey was appointed to investigate the matter (possibly Valette was handing the Englishman a vote of confidence; before the siege, he had been charged with accepting bribes). He determined that the explosion was accidental, but it was unnerving nevertheless, and that much powder was hard to lose. Valette sent word to Mdina asking them to make up the shortfall and to provide some twenty-three more kantars besides. With St. Elmo nearly ready to fall, he would need them.

Turkish guns surrounded the fort and kept firing the entire day, though almost to no purpose—at some points the bombardment had reached bedrock, and only the ditch lay between Christian and Turk, a ditch the Ottomans were doing their best to fill up with brush and rubble and whatever else came to hand. As the inevitable climax approached, the defenders of Fort St. Elmo seemed to have fallen into a calm acceptance of what was to come, which in turn encouraged daring and insouciance. The night of June 19, Pietro di Forli had himself lowered into the ditch, where he hoped to torch the bridge. He could not—the Ottomans had packed it with wet dirt (terra ben bagnata) and its defenders soon noticed him and began to shoot. Di Forli managed to return to the fort, where his companions followed up his efforts by dismantling a section of wall and firing chain shot at the bridge. This turned out to be a waste of powder, as they were unable to depress the angle of fire enough to actually hit the structure. However futile these efforts were, they at least gave proof that these men had by no means lost their spirit.

By now the space between Fort St. Elmo and Fort St. Angelo had become a watery no-man’s-land, but somehow Ramon Fortuyn, the knight sometimes credited with the invention of fire hoops, was able to cross over from Fort St. Angelo without incident to get a sense of how things stood. Miranda, more or less in charge despite himself, seemed a little surprised to see him and assured Fortuyn that it would be simple cruelty to send more men to die. Those remaining officers on St. Elmo—d’Eguaras, Monserrat—all said the same. Fortuyn would better serve the island by returning to St. Angelo and readying himself for the fight that would soon begin again at Birgu. All that remained was prayer. Accordingly, Fortuyn went back to Fort St. Angelo along with two Muslim standards captured in the last assault, standards that he ceremoniously presented to Faderigo de Toledo as a proxy for Don Garcia and King Philip.

Fortuyn’s report clearly disturbed Valette, and the grand master followed up the next night by dispatching a second emissary, the Chevalier de Boisbreton, along with an Italian brother Ambrogio Pegullo. A dangerous trip—the moon was just past full and the Turks were vigilant. Fra Ambrogio’s head was taken off by a cannonball. Boisbreton’s arrival must have stirred new, if unreasonable, hope within these men—why else had he been sent if not with good news? But nothing had really changed. The fort, they agreed, might be able to hold off one more Muslim assault, but no more. If they did hold off such an attack, and no help arrived from Sicily, it would be best to evacuate the fort at that time.

This was wishful thinking at best. Boisbreton managed to bring the news back to Valette, but only barely. Turgut’s engineers finally had extended their trenches to command the grotto from which Fort St. Elmo anchored its lifeline to Fort St. Angelo. By the same token, it would be impossible to get enough boats to ferry the men in St. Elmo safely across the water. In Turgut’s words, Fort St. Elmo, the child of Birgu, was now cut off from the mother’s milk and must soon fall and die.

June 20 also appears to be the last day that anyone in the Order had enough leisure to compose a daily situation report.

#

June 21, the feast of Corpus Christi. Soldiers, civilians, and men, women, and children lined the streets of Birgu. Inside the Church of St. Lawrence, the priest intoned the liturgy, raised the monstrance containing the host above his head, and then solemnly carried it into the daylight and through the streets—a demonstration to the faithful that God was not confined to the inside of a church but was everywhere with them. Valette and other knights, trading the red-and-white cloaks of martyrdom for the black-and-white of devotion, raised the poles to hold the canopy that shielded the container from the sun or rain. At the conclusion, Valette, “carrying his staff, served food to thirteen poor men,” as did others of the Order, replaying the message of love and charity at the core of the Order’s mission. To the sound of distant cannon fire, the procession trod the narrow stone streets among the people of Birgu, solemn, but with a care for current dangers—the route deliberately avoided those areas most at risk of Ottoman artillery.

Across the water, Ottoman forces had managed to create a breach on the scarp walls of the cavalier and hurried to exploit this bonanza. Quickly erecting a barricade against the gunfire and fire hoops of the Christians above them, they brought up four or five small culverines (capable of firing sixty-pound balls) and began to fire down into the central piazza. It took the men inside a few minutes to realize what had happened, and when they did, they fired back with small arms. When that failed to discourage the enemy, Monserrat ordered one of the few remaining cannons wheeled about. The gunners knew their business. They stuffed the barrels with scrap iron and stone, fired on the tower, and silenced the enemy position—at least, for the time being.

The end, however, was getting near. The sun went down, and as the exhausted Christians lay and waited, the cool night air carried the sounds from the Ottoman army of “the same prayers, rituals, and acts of superstition and false religion that had been heard the night before the previous assault.” There was no sleep, and so the defenders made the best use they could of the dark. Fifteen men under the Rhodian Pietro Miraglia (emulating the Italian Pietro da Forli) slipped into the ditch and attempted (unsuccessfully) to set the Ottomans’ bridge on fire before being chased back to the fort. The rest of the night was spent listening to the enemy’s prayers and chants as both sides prepared for the morning.

The attack came just after dawn and on every side. The Ottomans threw scaling ladders against the walls and were met by flying sacchetti, gunfire, trumps, and pikes. For six hours of repeated assaults, they chipped away at the defenders, never quite getting the upper hand. Several times the Ottomans planted their standards on the parapet, and each time the Christians pulled the banners down. On one occasion, the Muslims succeeded in mounting a portion of the wall, only to find that the siege cannon had left the masonry so unstable that it collapsed under their weight, throwing them down into the ditch below. From across the water, the guns on St. Angelo fired on the wooden bridge leading to the post of Colonel Mas. This was welcome help to the Christians inside the fort, who were running low on powder and soon forced to defend the breaches with steel.

Janissaries had also retaken their position near the cavalier and were again firing into the fort proper. Monserrat ordered the same gun that was so successful the day before to prevail again. For Monserrat it was a personal victory, and his last. Seconds later a bullet struck him in the chest, killing him instantly. The still-living were saved the trouble of burial when moments later cannon fire brought down a wall on his remains. After the siege was over, survivors “dug through the ruins of the fort and found his body, fully armed, his hands joined as if still in prayer to God.”

With Monserrat gone, rumors spread among the foot soldiers that d’Eguaras, Miranda, and Colonel Mas, all three of whom had not been seen since the last assault, had also been killed. This was easy to disprove. The three were all badly wounded, struck by bullets, arrows, and artificial fire, but still alive, or half-alive. They dragged themselves into view to encourage their men and to restore some sense of order. Mas and Miranda returned to their places on the line; d’Eguaras returned to his command post at the center of the piazza. Those still alive had neither the time nor the energy to bury the dead. Instead, they stacked the bodies against the walls to bolster the defenses. Even this gruesome expedience might delay the enemy and cost them a few more casualties, which was some consolation to the survivors.

Seven hours after the assault had begun, five hundred Christians lay dead, one hundred others wounded. They comprised the last of the fort, and yet, against all logic, the Turks still fell short of victory. Balbi claims that all Christian officers were now killed. The men waited in what is described as a day as hot as any fire. The next attack could come at any time, on any side, on all sides. Anyone not utterly incapable was at his post, weapon in hand. Mustapha toyed with these men, launching a series of feints, so many that no one bothered to keep a tally. Nightfall provided welcome relief from the sun at least, and time enough to tend their wounds, many of them serious.

All stocks of gunpowder were now empty, and the surviving defenders were forced to scavenge the powder horns of their dead comrades. They were able to get out one last communication to Fort St. Angelo. A single light swift boat shot out from the grotto under St. Elmo and managed to elude ten heavier Muslim craft. As backup, an unnamed Maltese swimmer followed suit, navigating a good part of his trip underwater. They reported that in St. Elmo “almost none healthy remained, and of those who were still healthy, all were exhausted, all soiled and stained by the blood, brains, marrow, and viscera of the dead colleagues and the enemy they had killed.” That the defenders would have only cold steel to fight with—Cirni refers to picks and spades—was almost an afterthought.

Men trapped in situations that must end in certain death can inspire a strange envy in outsiders. Having heard the last testimony from the fort, of its remaining defenders with their broken weapons, a large number of knights, soldiers, and citizens stepped forward to join the chosen few certain to die the next day. Romegas himself volunteered to lead them. Valette, who had masked his emotions with bluff heartiness and further talk of Don Garcia’s imminent arrival, refused to allow it. He did, however, agree that they might carry supplies to the beleaguered men, the first supplies in three days.

In the event, it didn’t matter. The moon was full and the Ottomans were on highest alert; and while a lone swift boat might, with some luck, successfully dart its way through, there was no hope of five cargo-laden boats lumbering over the water between St. Angelo and St. Elmo in safety. Piali Pasha, already humiliated by the last vessel out of St. Elmo, was in no mood to let another one back into the fort, and now led the flotilla to prevent any action in person. Romegas, outnumbered sixteen to one and target of a furious storm of cannon fire, gunfire, and arrows, chose to return back to Fort St. Angelo.

The chosen few remaining at Fort St. Elmo were now utterly alone. Without hope for victory, for rescue, or for mercy, they could only prepare themselves for a good death. “Seeing that all hope of survival was broken, being already certain, clear, and secure that they were to be taken and killed, and their fate delayed only so far as the hour of dawn; with great contrition they confessed to one another, asking forgiveness of God for their sins, and with his Divine Majesty, they devoutly reconciled themselves with no Sacraments other than a shared fraternal and devout embrace.”

Along with the soldiers, two friars, Pierre Vigneron and Alonso de Zembrana, one French, one Spanish, remained at St. Elmo. The two had tasks of their own to fulfill before sunrise. They entered the chapel, which now served as a hospital for the most grievously wounded, and delivered what last rites they could. This accomplished, the two brothers prised up a large paving stone and, putting it to one side, dug a hole in the earth below. Into this cavity they laid the gold and silver chalices and candlesticks and a reliquary containing a bone of St. John the Baptist. With the stone back in place, they proceeded to gather all remaining sacred objects—the tapestries that covered the walls, the wooden crosses and cloth vestments, the sacred books. All these they carried out of the chapel, piled up in the center of the fort, and set on fire. The Turks took this as a signal fire calling for help.

The pair made the circuit of the fort. They took confession from and conferred absolution on all those who remained alive in Fort St. Elmo in anticipation of imminent death. Then they, too, waited for the dawn.

#

June 23 was the eve of the feast of St. John the Baptist. Fort St. Elmo had held out for twenty-nine days, and the Ottomans were impatient to be done with it. Throughout the night, their thirty-six heavy guns fired from three points on land and several of Piali’s ships on the water, illuminating both the sky and the fort and proving if nothing else that they still had a vast amount of ordnance to waste. Dawn broke. The Muslim soldiers on Sciberras gazed up at the smoking ruins and saw the white-and-red crossed flag still flying, still defiant. Presently they made themselves ready for what would have to be the final assault. Across the water, the men at Fort St. Angelo, all too aware of what was coming and helpless to stop it, stood and watched the final act play out.

Inside St. Elmo scarcely sixty men remained, scattered among the breaches and placed in the remains of the cavalier, outnumbered by the dead, who lay where they had fallen. Few of those left alive had escaped injury; all were determined to hold on to the last instant. The captains were focused on a hard fight, a good death.

One more time the kettledrums pounded, brass horns shrilled, men shouted, and the order to advance was given. Mustapha reported to the sultan that his troops, “shouting ‘Allah, Allah!’ and accompanied by the souls of the martyred,” began to charge the walls. Janissaries, spahis, and their corsair allies, impatient for victory, crossed over the rubbish pit of stone, earth, and broken weaponry, climbed over the corpses, scrambled up the incline toward the breaches, and braved a single, weak volley from inside the fort.

If they expected the job to be easy, they were disappointed. The first Muslims into the breach were met with a hedge of sharp steel, pikes, swords, lances, and a hail of stones. An hour passed, and although men on both sides fell, the fort did not. Another hour passed, and the attackers fell back, re-formed, came forward again, and again were held off by the stubborn Christian line. Both sides licked their wounds and dragged their dead away. From time to time there followed small diversionary attacks of no particular consequence, each a prelude to the next general assault.

When the final assault came, the first Janissaries to cross the rise found, to their astonishment, Captain Miranda, strapped into a chair and gripping a pike. The commander was maimed and bandaged, but still possessed of the soldier’s skills of thrust and parry. Even now in a position of weakness he managed to slash and gut a handful of enemy soldiers before his fellow Christians were able to repel the attackers one more time. The Muslims, however, managed a final parting shot that killed Miranda.

Command now devolved on d’Eguaras. His leg had been shattered, and so he too was confined to a chair. Seeing how the number of his men had dwindled, he thought to improve the odds by consolidating his remaining forces. He ordered the gunners on the cavalier to fall back and join their comrades inside the fort. This move was a boon for the Muslims, who quickly moved to fill the cavalier with sharpshooters. From its heights they could look down inside the shattered fort and signal to their comrades just how diluted the Christian force truly was. All tactical advantage now lay with Mustapha. Marksmen on the ravelin and on the cavalier could fire down on the Christians from the rear while Muslim infantry could attack from the front and flanks. (Oddly, Balbi says that the Muslims confined themselves to throwing stones.)

A little past eleven that morning, the final assault began. Janissaries, corsairs, and anyone else who wanted to be in at the kill, drew their blades and overtopped the crumbling edge of the fort and poured into the main piazza. The area soon resembled a Roman amphitheater in the final stages of a gladiators’ show, a confused mass of desperate men fighting in separate brawls “in which there ran rivers of blood from the multitude of the dead and the wounded on all sides.” D’Eguaras was among the first to die. Knocked from his chair, he managed to raise his sword and limp toward four Janissaries. One of the four brought a scimitar down on his neck and severed his head, which Mustapha would later order stuck on the end of a pike.

With their comrades gone, not wishing to survive them, unable to see beyond the moment or to hope for a life in this world, the remaining Christians lashed out with a superhuman fury at any Muslim who came within reach. At the door of the chapel, Chevalier Paolo Avogadro swung a broad sword with both hands and soon created a half-circle of Muslim dead around him. It took a volley of arquebus fire to put an end to this slaughter, and the dying knight collapsed on top of the pile of men he himself had killed.

The few small fights were winding down as force of numbers made good the Ottoman effort to leave no man standing. Colonel Mas, last of the commanders and also confined to a chair, swung a two-handed sword until he was himself cut down. Fortunio Escudero, last gunner on the cavalier, headed a small group of soldiers wielding broadswords on the crest of the fort, clearly visible from across the water at Fort St. Angelo, until he and they too succumbed to greater Muslim numbers. Official reckoning was now only minutes away. Mehmed ben Mustafa, who had captured La Rivière on the first day of the invasion, had the honor of seizing the knights’ ragged banner for his general as well, after which he “entered the bastion of the infidels and chopped off some heads.” The end was marked when a wounded knight, Frederico Lanfreducci, went to his post at the marina and gave the final agreed-upon smoke signal (una fumata) that the fort was lost. Moments later he was taken prisoner, becoming one of nine Christian survivors captured in Fort St. Elmo’s last battle. A handful of Maltese, able swimmers, were able to escape.

The fight was over. It had taken four hours.