Fort St. Elmo.

Map of Grand Harbor

Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Sultan, had ordered that no action be taken without consulting Turgut Reis. Turgut still had not arrived. Some thought that he was not coming at all—he was old, and strange things happen at sea. There was no reason to hold up all operations on his account. Spain was a formidable power, more so now that they were not distracted by wars in the Lowlands and against France. They were quite capable of launching a relief force to trouble this siege, and intelligence suggested that, under the guidance of the new and capable viceroy, they were in the process of doing so. Best then to get on with the operation and hope that Turgut would show up sooner rather than later.

The leading commanders gathered in Mustapha’s tent to decide what to do next.

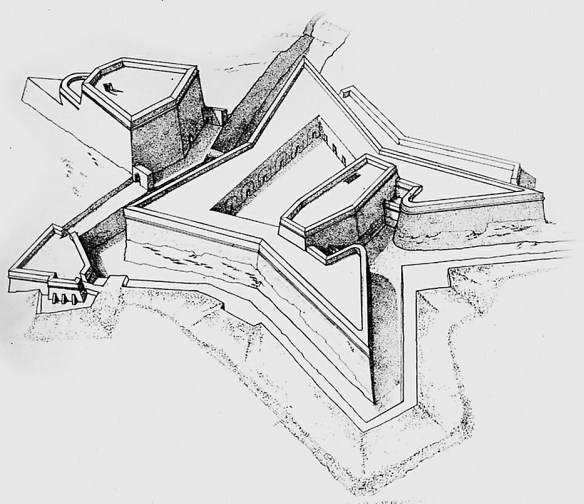

In theory there should have been little to discuss. The strategy had been laid out months earlier in Constantinople, aided by a scale model of Grand Harbor built on the report of two Muslim spies posing as fishermen. The plan was to take out Fort St. Elmo and so control the eastern-facing deep waters and the secure bay of the Grand Harbor, better protected than Marsaxlokk from the spring’s strong gregale winds that could sweep down from the northeast. In so doing, the Ottomans could maintain a supply base close to the army’s center of operations, thus simplifying the demands of logistics. All future matériel arriving from Constantinople or North Africa would not have to be hauled the eight miles overland from Marsaxlokk, a wearisome task at best, and a dangerous task so long as there were Christian marauders about—as, in fact, there were until the very end.

Mustapha had his own ideas. A veteran of wars in Hungary and Persia, Mustapha was accustomed to long marches over rough terrain—what was an eight-mile trek to him? Concede Grand Harbor to the knights, he thought, and St. Elmo becomes a Christian liability, a place they would have to defend while the bulk of Muslim soldiers were wearing down the main objectives elsewhere. His proposed order of operations was for Piali Pasha to take ten thousand men and ten guns and seize the lightly defended capital of Mdina at the center of the island. This would be both a psychological blow to the Maltese and a boost for his own men, and it would serve to protect the army’s rear from Mdina’s cavalry raiders and any possible Spanish relief forces. Once Mdina was taken, he could then attack the bulk of the enemy’s forces at Birgu and Senglea, and finally, almost as an afterthought, seize the island of Gozo. His vision went further, offshore and into Piali’s area of authority. He suggested a new disposition for the fleet, that it be divided into three parts: one to blockade Grand Harbor, one to remain in Marsaxlokk, and one to patrol the channel between Malta and Sicily.

It did not go down well. Piali Pasha reminded the council that his responsibility was to meet the needs of the sultan’s “powerful and invincible armada” and to guard the island from any Christian warships. (After his attempt to swindle Suleiman out of some ransom after Djerba, he was also on his best behavior.) Piali wanted the eastern-facing deep waters and secure bay of the Grand Harbor. To get this, they would need to take out the defensive Fort St. Elmo. The council, many of them navy men, concurred with Piali.

Compelled against his better judgment to target Fort St. Elmo, Mustapha wanted to know how long it would take to capture the place, and he sent out engineers skilled in this kind of calculation to make an estimate. They got as close as they dared, and came back with a mixture of good news and bad. The good news was that the shortcomings Don Garcia had criticized were all in place. The bad news was that the stony ground, while suitable for trenches, was useless for digging mines. As to siege artillery, that was simply a matter of getting cannon down the steep length of Mount Sciberras and into position opposite the fort. The engineers were confident that the Ottoman army, fresh from their voyage and ready for a fight, would be able to bring down the walls and take the fort in under five days. With luck, they might be able to present the first victory of the campaign to Turgut when he eventually arrived.

Mustapha gave in. His May 23 report to Suleiman notes the divided opinions and the final proposed course of action; it does not, interestingly, indicate what he thought.

Balbi describes this squabble in some detail, based on the gossip of two more renegades who had, they claimed, stood guard outside the tent. (In camps famed for their silence, shouting commanders were presumably easy to hear.) Gossip or not, an overjoyed Valette reacted swiftly. His spies in Constantinople had reported that St. Elmo was to be the first target, but he could not be sure. Initially he had entrusted its defense to the aging and unwell Fr. Broglio and a small contingent of Spanish foot. From his command center in Fort St. Angelo, he now ordered the French knight Pierre de Massuez-Vercoirin (aka Colonel Mas) and two hundred of his men, as well as sixty-five volunteers from the knights, dispatched to bolster the three hundred and thirty-five soldiers already in Fort St. Elmo. He cautioned them, however, to make self-preservation their priority, to not engage the enemy in any unnecessary skirmishes.

#

Now certain that the first target was to be Fort St. Elmo, Valette had all the civilians who had taken refuge there brought over to Birgu. The boats that carried this last group out of harm’s way returned with powder, lead, rope, incendiaries, hardtack, wine, cheese, lard, oil, and vinegar for the five hundred men inside. He also ordered Colonel Mas and 150 of his men to swell the ranks.

If Valette expected caution from the men at St. Elmo, he had sadly misjudged them. Inspired by the knowledge that Ottoman siege guns were being towed down the peninsula, Colonel Mas and Captain La Cerda led a number of their men out of the fort and headed for the enemy. The ensuing fight, the last direct fighting they were to enjoy for some time, was a short and spirited affair, but the handful of men killed on both sides did not materially slow Mustapha’s progress.

It appears, however, to have prompted him to position sharpshooters within range of Fort St. Elmo. Janissaries were notorious for the efficiency of their snipers, “most excellent marksmen.” These men could lie in wait for hours at a time in the hope of blowing the head off anyone who, from curiosity, might peek over the top of the parapet, however briefly. From that time on, the Christian defenders were trapped inside the fort, with only the sound of Muslim sappers digging trenches outside the fort and enemy gun carriages moving closer and closer.

The defenders, however, were able to fire cannon from seaward facing cavalier cannon fire that was supplemented by Valette’s men across the water at Fort St. Angelo. The footsoldiers might feel superfluous in such circumstances. These were experienced warriors who knew what went into a proper fort, and Fort St. Elmo was not the best example of the military architect’s art. Personal bravery notwithstanding, the men of Fort St. Elmo could calculate odds as well as any Ottoman engineer, and they knew the power of the wall-smashing guns that in a day or so would be brought to bear.

On May 24, Mustapha was ready. His guns were set in three ranks facing the landward side of St. Elmo. Defensive gabions, boxes filled with cotton, now created a wall through which ten guns capable of firing eight-pound balls poked out toward the fort. A second tranche that boasted two culverins, guns capable of lobbing sixty-pound shot, backed them up. Finally, on the rise overlooking the fort was one of the so-called basilisks, its vast cyclopean eye staring down on St. Elmo, a huge weapon capable of throwing a stone ball of a hundred and sixty pounds. More guns would follow, and from different emplacements, but these would do for now. Sacks of powder were shoved down the bronze gullets, with stone balls lifted in as a chaser. Engineers sighted targets and adjusted angles of fire. Each gunner prepared his slow match and blew the tip into a bright orange glow, loose sparks flying off and crackling as they expired. Mustapha himself stood behind them, waited until all was ready, and then gave the order to fire. The artillerymen lowered the linstocks to the touchholes, and in a storm of sound, fire, and smoke, the first volleys slammed into the walls of Fort St. Elmo.

The effect was devastating, so powerful that even in Birgu the houses shook. The infantry huddled inside the fort, unable even to watch the enemy. Throughout the day, Turkish artillery smashed against the walls, pulverizing and knocking off chunks of stonework and beginning to fill the ditch. Of necessity, trained soldiers became journeyman masons of the crudest sort, reduced to reinforcing the walls as the ground shook and stonework crumbled, their swords and guns and all thoughts of fighting now shelved. Men such as La Cerda could only seethe at this misuse of their talents.

The Christians of St. Elmo were not, however, fighting completely alone. Valette had ordered the guns on Fort St. Angelo to fire on the Ottoman sappers and cannon, and they did so with good effect. One of these shots dislodged a stone that struck Piali Pasha’s head and knocked him senseless. He was unconscious for about an hour, prompting rumors about his death—premature, as it happened. He had, they said afterward, his turban to thank for his life. Mustapha’s reaction to this news is unrecorded.

The entire day passed in ponderous rolling thunder of cannon fire, smoke, and dust quivering in midair. The very ground trembled in response to this pummeling. Finally, night fell, the cannon ceased, and the men at St. Elmo considered the situation. It was clear to them that the fort could not hold up under this kind of abuse, and since the defenders could not even fight back, the best option, the only option, was to abandon the fort entirely, return to Fort St. Angelo, and bolster the fighting force there.

If someone was to suggest this course of action to as stern a man as Valette, best that it be a reputable commander who was not a member of the Order of St. John. The job went to Captain La Cerda.

On the night of May 24–25, La Cerda slipped into a small boat and under a moonless sky was rowed across to Fort St. Angelo. Valette was there to greet him and in a public square asked him how matters stood at St. Elmo. The grand master presumably expected a bluff-and-hearty answer to the effect that they were holding their own and eager to fight. He got the opposite. La Cerda answered that matters were exceedingly bad.

It was a straightforward, honest, and heartfelt answer, but as the chronicler put it, one that “he should have kept secret and in chambers, so as not to frighten the populace.” He was quickly hustled into the council room before he could blurt out anything more. The grand council sat in tall back benches on either side of the room, unsteady candlelight wavered over the stones and wood, and the commanders asked him to explain himself. La Cerda didn’t hesitate. Fort St. Elmo was, he said, “a sick man in need of medicine.” Its walls could not hold, and the soldiers, his soldiers, were being condemned to die without hope of fighting back. Let the place be mined and abandoned so that Turks could enter and be blown up in the process. Let the Christians rejoin their fellows at Senglea and Birgu, and let the real fight begin.

The council might not have expected good news, but this kind of talk, this early on in the campaign, was a shock, the more so given the source. La Cerda was no raw recruit who flinched at the first sound of gunfire. He was a veteran of the 1543 siege of Tlemcen, on the Barbary coast, in which battle he had been wounded in his shoulder. His actions on Malta so far had been aggressive, even rash, but undeniably brave. Given his position and experience, his word must carry some weight, both with the council and with his own men.

How did Valette react? Accounts differ. However displeased the grand master might have been, the chroniclers Balbi and Cirni record a relatively temperate response. The encyclopedic Bosio, however, writes that Valette was scathing. He thanked La Cerda for his report. Did the men in the fort truly have no confidence in their abilities? Very well, they were free to go. Valette did not wish to have anyone in whom he could have no confidence, and clearly he could have no confidence in them. He would replace the men now in the fort with better men, braver men, men headed by Valette himself.

It may have been stage anger or the real thing, but regardless, the threat had its intended effect. The council protested that as grand master he must not leave. If more soldiers were required at St. Elmo, they could be found. Valette agreed in the end and called up Lieutenant Medrano, a subordinate to Captain Miranda (who was recovering from an illness at Messina) and ordered him to take his company of two hundred men across to Fort St. Elmo. Proving that good things come to those in whom Valette did have confidence, the grand master also promoted him to captain.

Not to be outdone by the Spanish volunteers, a French knight, Captain Gaspard de La Motte, stepped forward and offered to take a number of his own men to bolster the defenders of Fort St. Elmo. Would Valette agree?

He would. Ardent men, he said, were exactly what was needed. To top off the rebuke to La Cerda and any others at Fort St. Elmo who thought the place not worth defending, Valette also offered some sixty pressed convicts (forzati) their freedom if they would agree to act as ferrymen for the soldiers.

The sky was still dark. Captain Medrano, La Motte, and two hundred fresh troops (along with the humiliated La Cerda) embarked stealthily into the small crafts and under the last sliver of the old moon crossed the waters back to the crumbling fort. Valette wrote to Don Garcia that the fort’s complement was eight hundred men, though perhaps he was exaggerating a bit when he said “all were resolved to do their duty.”

If nothing else the incident demonstrates the degree to which auxiliaries, especially the Spanish soldiers like La Cerda, considered themselves to be the equals of the Order in terms of authority. Vertot, a seventeenth-century French historian for whom Valette could do no wrong, derides the Spaniard as someone “whom fear made eloquent.” The charge is ludicrous and ignores La Cerda’s logic, which in this instance was both simple and direct. He was on Malta to kill Muslims. In St. Elmo he was not killing Muslims. Better, therefore, to abandon a slaughter pen and take the fight to the enemy elsewhere. This was perhaps an admirable view, but impractical for Valette. The grand master’s was not a split command, much less command by consensus. Dissent was already a problem in the enemy camp, and Valette would not have it in his own.

And he did not let the matter drop. He quickly informed Don Garcia, who raised the matter with the king: “Juan de la Cerda and his lieutenant . . . have shown great baseness (vildad), and attempted to persuade the Grand Master to abandon the fort and mine it, because it was no longer possible to defend the place.” Don Garcia suggested that beheading would be suitable punishment, and the king, who took a minute interest in all details of his empire, did not object: “If what you say is true, that Juan de la Cerda and his lieutenant wanted to abandon Sant Telmo, you are to give orders that they be punished according to what is just.” Philip’s letter is dated July 7—it is a little touching that the king could imagine that he was addressing a situation static enough that his advice would be meaningful. Nothing further seems to have come of the matter, and as we shall see, La Cerda’s fate would be more complex than a simple execution.

#

The fight for St. Elmo, projected to take five days, was now on day nine, with no end in sight. Worse, it turned out that Turgut agreed with Mustapha’s abandoned strategy completely, and said so: “‘Of what use is it to take Saint Elmo?’ he asked. ‘Even if you had ten Saint Elmos, until you take Malta [i.e., the rest of the island], you cannot be conquerors.’ Thus having spoken, he immediately wept.” They should, he thought, have gone for Mdina and Gozo, the easy targets, the mother to the child St. Elmo.

It was too late now, though the endorsement of Mustapha’s plan, added to the soldiers killed by Piali Pasha’s guns, cannot have helped relations between Mustapha and Piali. It was best to look forward. Having received a full rundown of how matters stood, the aging Turgut immediately went out to the end of the peninsula to see firsthand what steps had been taken and what things could be improved. Turgut’s first concern was for the safety of his troops. He noted that the southward part of Sciberras was clearly visible from the walls of Fort St. Angelo. Given the expectations of a quick victory, Mustapha had had no reason to spend too much time in masking their actions. By now, however, Christian gunners from across the water had been able to calibrate their fire on sappers and artillerists, making the Muslims’ work both difficult and short. This interference had to be stopped. Turgut ordered a makeshift screen to be erected between Fort St. Angelo and the Turkish part of Sciberras. Blind the gunners to specific targets and they would be wasting shot and powder on empty space.

The men now relatively safe, Turgut turned his attention to the fort itself. A devastating bombardment was in order, and from as many directions as possible. Turgut ordered new artillery emplacements on Tigné point, the north tip of the harbor mouth. This would allow the Turks to fire on St. Elmo from three sides and force the defenders within to spread out their repairs. He was particularly interested in neutralizing the raised cavalier whose cannons faced back on the Ottoman lines at Mount Sciberras. Finally, he considered the matter of the Christians’ nocturnal relief boats. These vessels, all but invisible under the nearly moonless sky, had until now been largely unmolested. The moon, however, was waxing, and with each passing day, the Christians lost another sliver of advantage. Turgut was determined to end the fort’s cycle of slow bleeding and regular infusions, and just finish the fort off once and for all. The guns—thirty of various caliber—were to begin firing that night.