The German Waffen-SS “British Free Corps” (hereafter shortened to BFC), was the brainchild of John Amery. Amery, whose father was a Conservative MP in the English Parliament, found himself living within the shadow of his successful political parent and as such, he strove to excess to prove himself capable of making it on his own. With failures in these endeavors, it only drove him to more and he joined Franco’s Nationalists in Spain in 1936, being awarded a medal of honor while serving as a combat officer with Italian “volunteer” forces. Amery was a staunch anti-Communist and with all of his failings and money problems, he accepted the fascist doctrines of Germany. Following his tour in Spain, he resided in France, under Vichy rule. He ran afoul of the Vichy government (Amery was displeased with their mind set anyhow) and made several attempts to leave the area but was rebuffed. It was German armistice commissioner Graf Ceschi who offered Amery the chance to leave France and come to Germany to work in the political arena. Ceschi wasn’t able to get Amery out of France but later, in September of 1942, Hauptmann Werner Plack got Amery what he wanted and in October, Plack and Amery went to Berlin to speak to the German English Committee. It was at this time that Amery made the suggestion that the Germans consider forming a British anti-Bolshevik legion. So much so was Amery’s suggestions (in addition to the unit ) taken that Adolf Hitler himself made the motions for Amery to remain in Germany as a guest of the Reich and that Hitler thought highly of the idea of a British force to fight the Communists. The idea languished until Amery met up with two Frenchmen, friends of his, who were part of the LVF (Legion des Volontaires Francais ) in January of 1943. The two LVF men lamented about the poor situation on the Eastern Front but that they saw that only Germany was battling the Russians and thus, despite all, they should still lend support with their LVF service. Amery rekindled his British unit concept, wanting to form a 50 to 100 man unit for propaganda uses and also to seek out a core base of men with which to gain additional members from British POW camps. He also suggested that such a unit would also provide more recruits for the other military units made up of other nationals. It seemed that the Germans were already ahead of Amery and had already undertaken some consideration, a military order saying “The Fuhrer is in agreement with the establishment of an English legion…The only personnel who should come into the framework should be former members of the English fascist party or those with similar ideology – also quality, not quantity.” As it is to be seen, this last bit would prove to be very difficult to obtain.

With the go-ahead, Amery set down write two works which covered his German radio talks (which were allowed to be broadcast but with a disclaimer which stated his comments were not those of the German government) and that he suggested the unit be called “The British Legion of St. George”. Amery’s first recruiting drive took him to the St. Denis POW camp outside Paris. 40 to 50 inmates from various British Commonwealth countries were assembled. Amery addressed them, handing out recruiting material. The end result was failure. Still, efforts continued at St. Denis and finally bore some fruit. Professor Logio (an old academic man), Maurice Tanner, Oswald Job, and Kenneth Berry (a 17 year old deck boy on the SS Cymbeline which was sunk at sea ) came forward. Logio was released while Job was recruited away by the German intelligence, trained as a spy, and ended up being caught while trying to get into England and hung in March of 1944. Thus, Amery ended up with two men, of which only Berry would actually join what was later called the BFC. Amery’s link to what would become the BFC ended in October of 1943 when the Waffen-SS decided Amery’s services were no longer needed and it was officially renamed the British Free Corps.

With Amery’s initial recruiting methods being seen as a failure, another idea was to be tried in an attempt to woo POWs to join the BFC. Given the harsh conditions of POW camps in Germany and the occupied areas, it was decided to form a “holiday camp” for likely recruits from POW camps. Two holiday camps were set up, Special Detachment 999 and Special Detachment 517, both under the umbrella of Stalag IIId in the Berlin locale. These camps were overseen by Arnold Hillen-Ziegfeld of the English Committee. English speaking guards were used, overseen by a German intelligence officer, who would use the guards as information gatherers. But a Englishman was needed as possible conduit for volunteers and in this, Battery Quartermaster Sergeant John Henry Owen Brown of the Royal Artillery was selected. Brown was a interesting character. He was a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) but also a devout Christian. His ability to play both sides would serve him well. Captured on the beaches of Dunkirk in May of 1940, Brown eventually ended up in a camp at Blechhammer. Given his rank, he was made a foreman of a work detail and he also began to work into the confidence of the Germans. What Brown was doing, in reality, was setting up a black-market scheme, smuggling in contraband and using it to give to his men and also to buy off the guards. Later, Brown was taught POW message codes created by MI9 of the British intelligence service and he began to operate as a “self-made spy” as he called himself. With his status, he was called to be the camp leader of Special Detachment 517. At this time, another Englishmen, Thomas Cooper (who used the German version of Cooper, Bottcher, as his last name), arrived at the camp. Cooper, unable to obtain public service employ in England due to his mother being German, joined the British Union (the shortened name of the BUF) and eventually left England on the promise that he could get work in German with the Reichs Arbeits Dienst (RAD). As it turned out, this was not to be in the end and finally, he joined the Waffen-SS (who, unlike the Army, would take British nationalities). He was posted to the famous SS “Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler” (LAH), underwent basic training, then was placed into artillery training. This did not last for long and he was transferred to the infamous SS “Totenkopf” infantry training battalion. Trained all over again in infantry tactics, he was moved to the position of machinegun trainer with the 5th. Totenkopf Regiment and made an NCO, staying there until February of 1941 until moved to the Wachbattaillon Oranienburg unit outside Krakow, Poland. During this time, Cooper was reported (by post-war BFC men) to have participated in atrocities against Russian and Polish POWs and civilians, including the Jewish. In January of 1943, Cooper was transferred to the SS-Polizei-Division as a transport driver. The unit was posted to the Leningrad front and once in a Russian town called Schablinov, they were told they’d be put into the line to replace the mangled forces of the Spanish Blue Division. By February 13, 1943, the Russians went on the attack again and broke through the SS-Polizei lines. Cooper was wounded in the legs by shell splinters, evacuated out, and was awarded the Wound Badge in Silver, the only Englishman to obtain a combat decoration. During his recovery, Cooper came into contact with the camp and upon learning about the purpose, was given orders to join the project.

Brown, being a crafty and streetwise person, saw the real deal behind the camp and he correctly came to the conclusion that he was in a very unique position to both hinder the formation of the unit as well as obtain intelligence (and he also would make sure the men who came to the camp actually got a holiday). Brown set about winning the confidence of his German handlers and surrounds himself with trustworthy POWs and when the first batch of 200 POWs rolled into the camp, things did not turn out for the better. Brown and his men were doing their best to entertain the prisoners while Cooper and other pro-Nazi men worked the crowd, seeking ex-BUF members or other ex-Fascist group members as well as finding out attitudes about the Communists. However, this resulted in displeasure and many of the POWs wanted to be sent back to their camps. To try and qualm this, it was asked of the most senior British POW, one Major-General Fortune, to send a representative to the camp to inspect it and assure the men it was on the up-and-up. Brigadier Leonard Parrington was selected and was sent to the camp. He gave a speech, had a look at the facilities, and said it was indeed a holiday camp and not to worry. He did not know the real truth and took it for what it looked like. Brown did not feel safe in informing Parrington of the purpose of the camp. This visit was successful in calming the situation but when the POWs were sent back to their respective camps, only one confirmed recruit was gained, Alfred Vivian Minchin, a merchant seaman whose ship, the SS Empire Ranger, was sunk off Norway by German bombers. Others kept the BFC in mind as they were sent off. Brown, following the first batch, learned of the full scope of the project from Carl Britten. Britten said he’d been forced into the BFC by Cooper and Leonard Courlander. Brown was unable to persuade Britten to quit the BFC, but MI9 got a very revealing transmission from Brown.

A bombing raid against Berlin damaged a good portion of the camp prior to a second batch of POWs being brought in. It was decided to move the campmen to a requisitioned cafe in the Pankow district of Berlin, overseen by Wilhelm “Bob” Rossler, a Germany Army interpreter. Prior to the move, the BFC gained two members, Francis George MacLardy of the Royal Army Medical Corps ( he was captured in Belgium ) and Edwin Barnard Martin of the Canadian Essex Scottish Regiment ( Martin was captured at Dieppe in 1942 ). At this time, the BFC numbered seven. POWs continued to roll into the camp once repaired until December of 1944, when it was called to a halt. The reasoning was that the handling of the camp, as stated by Brown, was counter-productive to getting recruits for the BFC since the way the camp was run, fostered distrust. The reality was they had Brown as their front man, who was out for himself but also loyal to the Crown to continue his dangerous game of intelligence gathering and also deterring recruits from joining, which gained him, post-war, the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

Oskar Lange, who was overseeing the camps, hit upon another idea to gain recruits, and, it was hoped give him more stature. The earlier holiday camps only entertained long term POWs. Lange’s idea, however, was to take newly captured prisoners, who were still in a state of confusion, and work on them while they were vulnerable. This new camp was in Luckenwalde. The camp was headed up by Hauptmann Hellmerich of the German intelligence and his chief interrogator was Feldwebel Scharper. Scharper was not above using blackmail to get what he wanted and his tactics included fear, intimidation, and threats to coerce prisoners into joining.

The first group of POWs to be taken to Luckenwalde were mainly from the Italian theater. One such case of Trooper John Eric Wilson of No.3 Commando illustrated the techniques used by the camp. Upon arrival, he was stripped, made to watch his uniform get ripped to bits, then was given a blanket to cover up with. Placed in a cell with only the blanket and fed 250 grams of bread and a pint of cabbage soup, he was only allowed out to empty the waste bucket. After two days like this, he was taken before a “American”, who was in fact Scharper. Wilson was asked his rank, name, number, and date of birth (to which Wilson lied about his rank, saying he was a staff sergeant) then returned to his cell. Left alone, a “British POW” would come in from time to time, offer smokes and conduct idle chit-chat. The end result was that the isolation and the mistreatment led to him holding on to the “POW” who showed kindness to him and when dragged before Scharper some days later and offered the choice of joining the BFC or staying in solitary, it can be understood that Wilson chose the BFC. With this initial success, it was deemed this method would be the gateway to expanding the BFC and in turn, 14 men were made to join, including men from such esteemed units as the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and the Long Range Desert Group.

However, things fell apart when these men, told they would be joining a unit of thousands, ended up in the billets of the cafe and the unit amounted to a handful of men who were more out for the opportunity of freedom or Fascist in leaning. At this time, Edwin Martin attempted to take advantage of the discord (perhaps to atone for his role in the camp) to disrupt the BFC but it did not have the desired effect. Two of the men broke away from the cafe and get into the holiday camp 517 to report to Brown who then complained to Cooper. Cooper then addressed the men at the cafe billet and in turn, those who did not want to remain could leave (though, to prevent the truth about the BFC reaching the general POW population, these men were isolated in a special camp) and by December of 1943, the BFC had only 8 men.

In spite of the tiny size of the unit, the Waffen-SS continued to work on the BFC. The first step was to appoint an officer. Because of the nature of the BFC, the candidate had to be trustworthy, have a good understanding of English, and also be a skilled leader and have excellent administrative. This job fell to SS-Hauptsturmfuhrer Hans Werner Roepke. A very educated man, Roepke’s grasp of English came from his time as an exchange student prior to the war. His military service included being a private in the Reichswehr, then as a law man with the Allgemeine-SS, before being called up to duty as a flak officer with the SS-Wiking division. He was made the commander of the BFC in November of 1943. Roepke’s first order of business was to determine just what goal of the BFC was and its principles. The first order of business was the name. “The Legion of St. George” was tossed out as being too religious and the “British Legion” was rejected as well since it was in use by a UK World War 1 veterans group. It was Alfred Minchin who suggested “British Free Corps” after reading about the “Freikorps Danmark” in the English version of Signal magazine. Thus, it was accepted (though, in correspondence, the unit was sometimes called the “Britisches Freikorps”) officially as the “British Free Corps”. That settled, Roepke moved on the purpose of the unit. All the current members told Roepke they wanted to fight the Russians (as you will see, this was more of telling the Germans what they wanted to hear) and so, with that settled, it was ordered that the BFC must swell to create at least a single infantry platoon, or 30 men. It was also decreed that no BFC member could be part of any action against British and British Commonwealth forces nor could any BFC member be used to intelligence-gathering. The BFC would be, until a suitable British officer joined the unit, under German command. Other things worked out included the fact that the BFC members would not have to get the German blood tattoo, they did not have to swear an oath of loyalty to Hitler, nor were they subject to German military law. They would receive the pay equal of the German soldiers for their rank. Finally, it was decided to equip the unit with standard SS uniforms with appropriate insignia.

Roepke put in the order for the BFC to be moved to the St. Michaeli Kloster in Hildesheim and he also put in the order for 800 sets of the special BFC insignia to the SS clothing department. Officially, the BFC came into existence on January 1, 1944. By February of 1944, the BFC made the move to Hildesheim and the Kloster, which was a converted monastery, now the SS Nordic Study Center and also the barracks for foreign workers laboring for the SS. Prior to the move, things for the BFC men were pretty idle but after the move, recruiting was to be stepped up. Of the group who left the BFC in December, the rumor that they would be sent to a SS run stalag, caused some of them to rethink their decision and three of them returned. Two new recruits were gained, including Private Thomas Freeman of the 7 Commando of Layforce. Freeman was to be the only BFC man who did not receive any punishment post-war for his membership, as MI5 stated his only purpose for joining the BFC was to escape and also to sabotage the unit. At this time, Roepke ordered all of the BFC men to assume false names for official documents but some did not do so. The BFC were also issued their first SS field uniforms, but without any insignia. Tasks were now assigned to the BFC members as well, which lead to some factionalism. Despite having duties, the majority of the time was spent being idle once simple chores such as cleaning the billets and such were done.

This idleness was to Freeman a chance to ruin the BFC by going after those who weren’t Fascist or strong anti-Communist. By gaining them to his side, especially since the main pro-Nazi BFC men were often away from the barracks, Freeman sought to form a rift in the unit. He was able to go on one of the recruiting drives (which were still being carried out) and even get ahead of the line to being made the senior NCO of the BFC. Freeman’s purpose for going on the recruiting drive was to gain men for his own ends. It netted three men, though one left soon after, being returned to his camp.

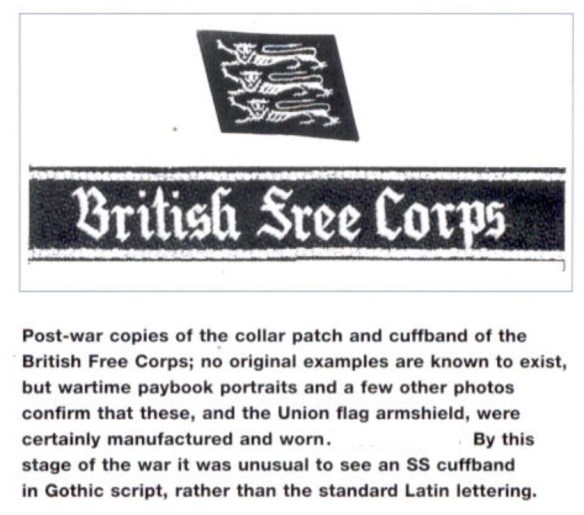

In April of 1944, the BFC was issued its distinctive insignia, the three-lion passant collar tab, the Union Jack arm shield, and the cuff title bearing “British Free Corps” in Gothic-script. Britten, who had been tasked as the unit tailor, spent most of a day sewing all the items onto the BFC member’s tunics. On the morning of April 20, 1944 (which was Hitler’s birthday), the BFC was paraded in full uniform and addressed by Roepke who said that now that the BFC was full-fledged ( by being issued uniforms, weapons, and pay books ), recruiting can begin in earnest. Promotions were also handed out at this time, with Freeman getting his NCO slot. Following the parade, the BFC members went off to various camps throughout Germany and Austria. The idea was to send the men to camps which they had been formally interned in. The idea, however, was very flawed and did not help recruiting in the slightest. All told, this recruiting drive netted six new members. During one such drive, Berry confided in a camp leader about his predicament, the leader saying he should seek out the Swiss embassy in Berlin, which Berry did not follow up on. Two of these recruits, John Leister and Eric Pleasants, both not wanting to get involved with the war, got caught up in it when the Germans took over the Channel Islands and put them both the camps since they were of military age. While not initially taking up the BFC offer, they talked it out and if the BFC should return, they’d join up. Why? Because the both of them were tired of slim food rations, did not like being away from the company of women, disliked the camp life, and also because the both of them hated being deprived of their freedom for a war they wanted no part in. In fact, Pleasants even admitted to Minchin and Berry that he “was in it to have a good time.”

All of the drives found the BFC numbering 23 men. This worried Freeman because if the unit reached 30, then the BFC would be incorporated into the SS-“Wiking” division and sent into action. To prevent this, Freeman took it upon himself to stop it. He drafted a letter, signed by him and 14 other BFC men (mostly the newcomers), requesting they be returned to their camps. This threw the BFC into chaos and it took pressure from Cooper and Roepke to just have Freeman and one other instigator tossed out and into a penal stalag, both being charged with mutiny on June 20, 1944. Freeman escaped the stalag in November of 1944, making it to Russian lines where he was repatriated in March of 1945. Still, the BFC was rattled and tensions between members were evident, made worse by Cooper seeking to instill SS-style discipline and methods, which was alien to the Englishmen whose experience with the British army was more lenient. With Freeman gone, Wilson was made senior NCO, which was a mistake given Wilson had lied upon his capture about his rank, and thus had little experience leading men and had a large appetite for women, which only being with the BFC could provide him with the freedom to partake of the female virtues.