All this time John Frost’s men had been defending their positions at the Arnhem road bridge, waiting in vain for relief, either from their own division or from ground forces coming up from the south.

The composition of the force at the bridge did not change at all after most of the 2nd Battalion’s B Company and the other men who had been trying to make a crossing at the pontoon area came into the bridge perimeter, so the men who found themselves there on that Monday afternoon would be the ones who fought that gallant action which has passed so powerfully into airborne history. The exact number of men who formed the bridge garrison will never be known; what follows is the best available estimate:1

2nd Parachute Battalion: Battalion HQj HQ, Support and A Companies; B Company (less most of No. 4 Platoon) – 340 men.

1st Parachute Brigade HQ including Defence Platoon and Signals Section – 110 men.

1st Parachute Squadron, RE: HQ; A Troop; most of B Troop – 75 men.

3rd Parachute Battalion: C Company HQ; most of No. 9 Platoon; part of No. 8 Platoon – 45 men.

1st Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, RA: HQ; B Troop; one gun team of C Troop – 40 men.

250 Light Composite Company, RASC: No. 3 Platoon – 40 men, plus Major David Clark from Divisional HQ, RASC.

9th Field Company, RE* part of No. 2 Platoon – 30 men.

In addition there were an estimated 59 men from various units: 17 glider pilots, all or nearly all from B Squadron arriving with antitank guns; 8 men of the Reconnaissance Squadron under Major Gough; 12 men from Royal Artillery forward observation officer parties; 6 men of the RAOC; 5 men each from the REME and Intelligence Corps; 2 or 3 Military Police; 2 men from the ‘Jedburgh’ team; and one war correspondent.

The total force at the bridge thus numbered an estimated 740 men, equivalent to less than one and a half parachute battalions. Although many of those men were not trained to the standards of a parachute battalion, nearly all had valuable combat potential. Less than half of the force was from the 2nd Battalion. There was only one lieutenant-colonel – John Frost – but there were no less than thirteen majors among the sixty or so officers present. There was a good cross-section of units available, but one element not present would be sadly missed: there was no part of 16 Parachute Field Ambulance there. It had been anticipated that there would be easy evacuation of seriously wounded cases to that unit’s location at St Elizabeth Hospital, but that did not happen. Captains J. W. Logan and D. Wright, the medical officers of the 2nd Battalion and Brigade HQ, and their orderlies would have to treat all the wounded without any assistance from surgical teams.

Monday

Only one corner of the perimeter had been attacked during the night. This was a library or small school on the eastern side of the lower ramp held by Captain Eric Mackay and some men of A Troop, 1st Parachute Squadron. There were several covered approaches to what was really an exposed outpost, and the Royal Engineers found it difficult to hold. Sapper George Needham says:

We had started to prepare it for defence – smashing the windows and pulling down the curtains – but we had only been there about ten minutes when the Germans attacked, throwing grenades into the rooms. The building was too vulnerable, so Captain Mackay ordered us out, into the larger school building next door, where we joined B Troop. They objected and said, ‘Bugger off; go find your own place’, but Captain Mackay, being the man he was, persuaded them in no uncertain terms to let us in, and we started fortifying some of the empty rooms.

(The Royal Engineers were later joined in the school by Major ‘Pongo’ Lewis, the 3rd Battalion’s company commander, and twelve of his men. There was some argument after the war between the sappers and the infantry over who was in command in this building, the Van Limburg Stirum School, during the subsequent three days of its defence. Captain Mackay, in an article in Blackwood’s Magazine, claimed to have been in command and never mentioned the presence of the 3rd Battalion men. Major Lewis, in his short official report, did not mention the larger RE party. Both officers had been allocated this position separately, in the dark of that first night, and Major Lewis, though clearly the senior officer, probably did not interfere with Captain Mackay’s handling of the larger sapper party.)

Dawn found the airborne men prepared for a day that would be full of incident. They had completed the preparations for the defence of the buildings they had occupied by breaking all the windows to avoid injury from flying glass, moving furniture to make barricades at the windows, filling baths and other receptacles with water for as long as the supply remained functioning; these were all basic lessons learned in their house-fighting training. As soon as it started to get light, Major Munford wanted to begin registering the guns of No. 3 Battery of the Light Regiment on to likely targets:

There was some reluctance to allow me to do this. Some people were still harking back to the time the paras had suffered from the results of ‘drop-shorts’ in North Africa – not by the Light Regiment. But I persisted and was allowed to register on the approach road at the south end of the bridge – only about six rounds – but we got both troops ranged on to it and recorded it. ‘Sheriff’ Thompson, back at Oosterbeek, said it should be recorded as ‘Mike One’; ‘Mike’ was ‘M’ for Munford. Our signals back to the battery were working well.

The first intruder into the area was a lorry ‘full of dustbins clattering in the back’ which drove in between the buildings overlooking the ramp and the offices which Brigade HQ was occupying. Trigger-happy airborne men shot it up from both sides; the driver, presumably a Dutchman on a routine refuse-collection round, was probably killed. A similar fate befell three German lorries which appeared, probably also on a routine errand and not knowing of the British presence.

But attacks soon started, mainly from the east. The Germans did not know the precise strength or location of the British force, and the first attacks were only tentative probes by some old Mark III and IV tanks supported by infantry which were easily beaten off. One tank reached the road under the bridge ramp and was fired upon by an anti-tank gun. Lieutenant Arvian Llewellyn-Jones, watching from a nearby building, describes how an early lesson about the recoil of a gun in a street was learned:

The gun spades were not into the pavement edge, nor firm against any strong barrier. The gun was laid, the order to fire given, and when fired ran back about fifty yards, injuring two of the crew. There was no visible damage to the tank. It remained hidden in part of the gloom of the underpass of the bridge. The gun was recovered with some difficulty. This time it was firmly wedged. The Battery Office clerk, who had never fired a gun in his life, was sent out to help man the gun. This time the tank under the bridge advanced into full view and looked to be deploying its gun straight at the 6-pounder. We fired first. The aim was true; the tank was hit and it slewed and blocked the road.

These early actions were followed by a period of relative calm, described by John Frost as ‘a time when I felt everything was going according to plan, with no serious opposition yet and everything under control’.

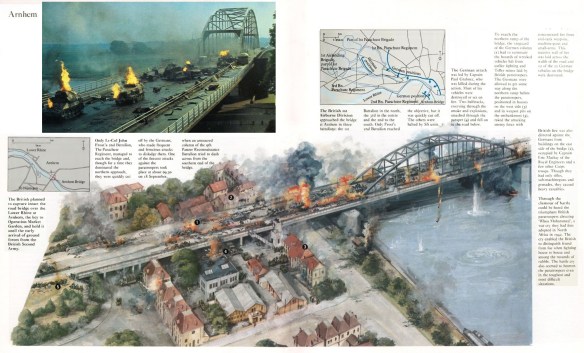

Hauptsturmfiihrer Viktor Graebner was the commander of the 9th SS Panzer Division’s Reconnaissance Battalion, a unit of first-class troops well equipped with twenty-two armoured cars and halftracked armoured personnel carriers. Only the previous day his divisional commander had presented him with the ribbon and emblem of the Knight’s Cross, awarded to him for bravery in Normandy. He had then led his unit over the bridge, before the British arrived there, on a sweep down the main road to Nijmegen. Finding that area all clear, he turned back and was now preparing to return over the bridge to reach his divisional command post in Arnhem. He knew the British were at the north end of the bridge now; whether he actually intended to mount an attack or just dash through the British positions is not known.

Look-outs in the top rooms of the houses occupied by the airborne men drew to the attention of their officers the column of vehicles assembling on the bridge approach. The identification of the vehicles as German swiftly put paid to the initial hope that this might be the head of the ground-force column making excellent time and arriving to relieve the airborne force. Major Munford saw that the German vehicles would have to pass through the area he had registered as a target, and his signaller immediately made contact with the battery at Oosterbeek. Dennis Munford says:

I received permission to open fire and, when the German column moved off, all I had to do was call, ‘Target – Mike One’, and the boys at the battery did the rest. There was no need for further correction. The Germans had to drive through it. I ordered a cease-fire when they left the Mike One area and came on to the bridge; I didn’t want to damage the bridge.

The artillery fire was accurate. Some German motorcyclists were seen to be hit, but the shells were too light to inflict much damage on the armoured vehicles.

The first part of Graebner’s force set off over the bridge at top speed. These leading vehicles were armoured cars which threaded their way round the still burning lorries from the previous night’s action and over the string of mines laid on the roadway during the night, but these failed to stop the vehicles. The airborne men held their fire until the last moment, and some of those first armoured cars drove straight on through to the town without being stopped, but then the order to open fire was given and none of the other armoured cars survived the resulting hail of fire. More and more of the German unit were committed to reinforce the attack, including half-tracks packed with soldiers, some protected by armoured coverings but others with open tops. Nearly all the German vehicles were hit and stopped in a great tangle on the ramp between the houses on both sides occupied by the 2nd Battalion’s A Company and also overlooked by the Brigade HQ and other buildings. Piats accounted for some of these vehicles, but much of the damage was caused by two anti-tank guns. One of these, Sergeant O’Neill’s gun of B Troop, was at a corner of the Brigade HQbuilding. The other 6-pounder was that of Sergeant Cyril Robson of C Troop, which was in a street closer to the river on the west side of the bridge and considerably below the level of the ramp. Directed by Lieutenant Tony Cox in the window of the house above him, Robson fired solid-shot shells at the parapet at the side of the bridge until he cut a V-shaped section away and was then able to fire into the sides of the German vehicles passing the gap. It is believed that Robson’s gun destroyed more of the attacking vehicles than any other weapon. The Germans in the half-track personnel carriers which were hit or found their way blocked were exposed to a hail of small-arms fire, trapped in their vehicles or spilling out on to the open stretch of the ramp, unable to deploy into shelter. They were slaughtered. One of the early victims was seen to be flung out on to the roadway and literally cut to pieces by a hail of fire. Some of the vehicles toppled over or slewed off the embankment of the lower ramp, allowing the airborne men in the buildings there to join in the execution.

Nearly everyone in the British garrison joined in the firing. Major Freddie Gough was seen enthusiastically firing one of the machine-guns on his Reconnaissance Squadron jeep. It would be ironic if it was one of his shots that killed his opposite number, because Hauptsturmfuhrer Graebner was among the German dead. Lieutenant-Colonel Frost was not firing: ‘I was watching other people and picking up information. A commander ought not to be firing a weapon in the middle of an action. His best weapon is a pair of binoculars.’

Here are two typical descriptions of the action. Corporal Geoff Cockayne was in the Brigade HQ building:

I had a German Schmeisser and had a lot of fun with that. I shot at any Gerry that moved. Several of their vehicles – six or seven – started burning. We didn’t stay in the room we were in but came out to fire, keeping moving, taking cover and firing from different positions. The Germans had got out of their troop carriers – what was left of them – and it became a proper infantry action. I shot off nearly all my ammunition. To start with, I had been letting rip, but then I became more careful; I knew there would be no more. I wasn’t firing at any German in particular, just firing at where I knew they were.

Signalman Bill Jukes was in the 2nd Battalion HQ building:

The first vehicle which drew level with the house was hit, and the second rammed into it, blocking the roadway. The rest didn’t stand a chance. The crews and passengers, those still able to, began to pile out, and those of us armed with Stens joined in the general fusillade. One of the radio operators grabbed my Sten gun, which was leaning against the wall, but I snatched it away from him, telling him to go and get his own. I hadn’t waited five years to get a shot at the enemy like this only to be denied by some Johnny-come-lately to the section. It was impossible to say what effect my shooting had. There was such a volley coming from the windows along the street that nobody could have said who shot who. At least one German lived a charmed life that day. He slipped out of one of the half- tracks on the far side from us and ran for dear life between the houses on the other side of the ramp and disappeared from view. Anybody with that kind of luck should live for ever.

This action lasted for about two hours. Various reports put the numbers of vehicles hit and stopped, or jammed in the wreckage of other vehicles, at ten, eleven or twelve, mostly half-tracks. The number of Germans killed is estimated at seventy. The electrical system of one of the knocked-out vehicles on the ramp short-circuited, and the horn of the vehicle emitted ‘a banshee wailing’ after the battle from among the shattered and burning vehicles and the sprawled dead of the attack. The morale of the airborne men was sky high; their own casualties had been light.

That attack by the Germans over the bridge proved to be the high point of that first full day. After the attack was over, John Frost reviewed the situation of his force. He had left B Company at the pontoon area, 1,100 yards away, in the hope that it might assist the remainder of the brigade into the bridge area. His last wireless contact with the other battalions showed that the 1st Battalion was still at least two miles away on the outskirts of Arnhem and making only slow progress; there was no contact with the 3rd Battalion and no sign that it was any closer. Frost had earlier decided that B Company was in danger of being surrounded at the pontoon while performing no useful function there and had ordered it to come in. It has already been told how Major Crawley extricated most of his company but lost one platoon cut off. Frost met Crawley and directed him to occupy some of the houses in a triangular block of buildings on the western part of the perimeter to provide an outer defence there. After B Company’s casualties the previous day and the loss of No. 4 Platoon, there were only about seventy men in the company. Captain Francis Hoyer-Millar describes how Company HQ was greeted when it occupied its house:

The lady – elderly, but not old – didn’t seem to mind us fighting from her house, smashing windows and moving the furniture about, but she took me into one room and said, ‘Please don’t fire from here; it’s my husband’s favourite room’; he was away somewhere. We couldn’t agree with her of course, and anyway, the house burned down in the end.

Later in the day Sergeant-Major Scott came in and reported that our last platoon commander had been killed – ‘Mr Stanford’s had his chips.’ Doug Crawley and I were both distressed, not at the seeming callous manner of the report, but that we had no more platoon commanders.

Lieutenant Colin Stanford was not dead. He had been shot in the head while standing on the top of his platoon building studying the surroundings through binoculars, but he survived.

The next serious event was a sharp German attack from the streets on the eastern side of the perimeter against the houses defended by Lieutenant Pat Barnett’s Brigade HQ Defence Platoon and various other troops. Preceded by an artillery and mortar bombardment, two tanks led infantry under the bridge ramp and into the British positions. In a fierce action, the two tanks were claimed as knocked out and the infantry driven back. One tank at least was destroyed by Sergeant Robson’s anti-tank gun and possibly one by a Piat. The 75-millimetre battery back at Oosterbeek was also brought into this action, its fire being directed on this occasion by Captain Henry Buchanan of the Forward Observation Unit, a good example of the way this unit’s officers operated with battalions as extra observation officers for the Light Regiment until the guns of the ground forces came into range, but Buchanan would be killed on the following day.

The remainder of the day saw further minor attacks. One of the buildings on the eastern side of the perimeter held by part of No. 8 Platoon, 3rd Battalion, was overrun, and another, held by part of the Brigade HQ Defence Platoon, had to be abandoned, but no further ground was given. There then commenced a general shelling and mortar fire which would harass the British force throughout the remaining days of the bridge action. Both sides were settling down to a long siege. The day had been a most successful one for the airborne men. Their positions were almost intact, and every attack had been beaten off with heavy loss of German life. Up to three tanks and a host of other armoured vehicles had been destroyed. British casualties had not been heavy. The best estimate is that only ten men had been killed and approximately thirty wounded before nightfall from all of the British units present. But the force was clearly isolated, unlikely to be reinforced in the near future and likely to be the subject of increased German pressure; the Germans badly needed the bridge to pass reinforcements down to the battle now raging in the Nijmegen area. These reinforcements were being laboriously ferried across the Rhine further upstream at present. Another danger was a looming shortage of ammunition; profligate quantities had been expended during the day, and the last issue from the supply brought in by the RASC would be made that night.

A change in the command structure took place that evening. All through the day, Lieutenant-Colonel Frost had been directing the actions only of the 2nd Battalion. Major Hibbert had been running Brigade HQ and the other units, carrying out as far as possible the plan brought from England and hoping that Brigadier Lathbury would soon arrive. But Hibbert now heard, from a wireless link with the 1st Battalion, that Lathbury was missing and he formally asked Lieutenant-Colonel Frost to take over the running of the entire force at the bridge. So John Frost moved over to the Brigade HQ building, leaving his second in command, Major David Wallis, in charge of the 2nd Battalion. At 6.30 p.m. Frost heard from the 1st Battalion that it was stuck near St Elizabeth Hospital and that the 3rd Battalion was nearby. Frost, acting now as brigade commander, ordered both battalions to form a ‘flying column’ of at least company strength to reach the bridge before midnight. But neither battalion had the strength or the means for such an operation, and this was the last attempt John Frost would make to exercise command over the other units of the brigade.

This may be a suitable place to mention Dutch dismay at the failure to use local means of communication and to utilize more fully the services of the Dutch Resistance. All through the day just passed, parts of the local telephone service had been functioning normally, but because of official British fear of German penetration of the Resistance, units had been ordered not to use the telephone. Another Dutch complaint is over the failure to trust more local men as guides; this would have been of particular help to the battalions trying to get through to the bridge. Albert Deuss, one of the local Resistance survivors, says:

If they had trusted us, we could have brought them through houses and got them through to the bridge, but they did not trust us and preferred to fight through the tanks. We knew our own town and where our friends were and all the short cuts. We even had a special password from ‘Frank’, our contact in Rotterdam, and we expected the British to know all about it – but they did not.

The only Dutch officer at the bridge, Captain Jacobus Groenewoud, had been using local telephones, but only to contact the loyal names on his ‘Jedburgh’ list to ascertain where the known German sympathizers in Arnhem were.

The airborne men prepared to face their first full night at the bridge. The houses on the western side of the perimeter had hardly been attacked, so part of B Company was redeployed to the eastern sector. A house near the bridge was deliberately set on fire to illuminate the bridge area, and B Company was ordered to send out a standing patrol to make sure no Germans came across the bridge during the night and also to protect a party of Royal Engineers which was sent to examine the underside of the bridge to ensure that the Germans could not demolish it. Captain Francis Hoyer-Millar was in command of the B Company patrol:

I was told to take twelve men out. We went past the wrecked vehicles on the ramp and on to the bridge itself. It was a large expanse of open area, quite dark. I didn’t know what was over the top of the slope so I threw a grenade. We were surprised when five Germans emerged with their hands up; three of them were wounded. I don’t know how long they had been hiding there, almost inside our perimeter.

I put half of my men on either side of the road. We had no trouble from the Germans but we were annoyingly fired on by a Bren from the houses held by our men. I yelled, ‘Stop firing that bloody Bren gun. It’s only me.’ It was one of those silly things one says on the spur of the moment. John Frost got to hear about it and he always teased me about it afterwards.

It was soon after dark that John Frost lost his long-standing friend and second in command, Major David Wallis, who only that afternoon had been made acting commander of the 2nd Battalion. Major Wallis was making his rounds in the darkness and came to the house defended by A Company HQ and some sappers of the 9th Field Company. As he was leaving the rear of the house there was a burst of fire from a Bren gun, and Major Wallis was hit in the chest and died at once. The shots were fired by one of the Royal Engineers. A brother officer of Major Wallis says that he was known to ‘have a habit of speaking rather quietly and indistinctly, and his answer to the sentry’s challenge may not have carried or not have been understood’. A comrade of the unfortunate sentry says: ‘It was at a time when the next shape in a doorway could be the enemy, such was the proximity of the fighting; response time was very short, and a German grenade had a short fuse.’ The death of this officer resulted in another command change. John Frost appointed Major Tatham-Warter to command the 2nd Battalion; this was over the head of the more senior Major Crawley. Frost was ‘aware of a slight resentment, but Tatham-Warter was well in touch with the battalion positions and I chose him’.

Soon after 3.0 a.m. (on Tuesday) there was a one-sided action at the school building jointly manned by sappers of the 1st Parachute Squadron and 3rd Battalion men. A German force which had probably misidentified the building in the darkness assembled alongside it, standing and talking unconcernedly, directly under the windows manned by the airborne men on the second and third floors. Typical of the disputed history of that building’s defence, Captain Mackay says that he organized what happened next while Lieutenant Len Wright of the 3rd Battalion claims that Major Lewis did so. This is Len Wright’s description of events:

We all stood by with grenades – we had plenty of those – and with all our weapons. Then Major Lewis shouted, ‘Fire!’, and the men in all the rooms facing that side threw grenades and opened fire down on the Germans. My clearest memory was of ‘Pongo’ Lewis running from one room to another, dropping grenades and saying to me that he hadn’t enjoyed himself so much since the last time he’d gone hunting. It lasted about a quarter of an hour. There was nothing the Germans could do except die or disappear. When it got light there were a lot of bodies down there – eighteen or twenty or perhaps more. Some were still moving; one was severely wounded, a bad stomach wound with his guts visible, probably by a grenade. Some of our men tried to get him in, showing a Red Cross symbol, but they were shot at and came back in, without being hit but unable to help the German.

The defenders suffered no casualties.