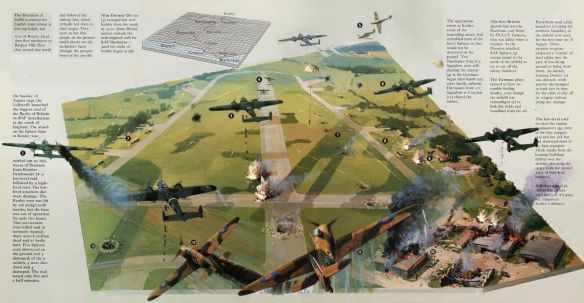

While this was going on, nine Do 17s from 9./KG 76 under Hauptmann Joachim Roth were about to cross the Channel at wave-top height. The German plan was that twelve Ju 88s from II./KG 76 would begin by dive bombing Kenley air base, after which the nine Do 17s from 9./KG 76 would take advantage of the confusion among the defenders to carry out a low-level attack on the same target. Meanwhile, KG 1 carried out a high altitude attack against the Biggin Hill airfield using sixty He 111s.

But the German plan failed. The purpose of Hauptmann Roth’s formation flying so low was to avoid detection by the British radar stations. This was successful, but when the nine planes surprisingly came thundering in over the coast at Beachy Head, it had a different effect than the Germans expected. The report from the British air observers worried Park, who had take-off orders sent to Kenley and Biggin Hill, where the Hurricanes and Spitfires from 32, 64, 610 and 615 squadrons were scrambled. Thus a second wave of British fighters was airborne further inland, as yet unaffected by the Bf 109s’ intrusion.

To top it all, the high-altitude and dive bombers were very late. The morning’s clear weather had been replaced by increasing rain, which made the other German bombers lose a lot of time climbing above the clouds before they could assemble in combat formations. The crews on board the low-flying Dornier planes were never informed of this, so they therefore became the first attack wave.

Hauptmann Roth’s nine Do 17s followed the Brighton – London railway northwards. The tracks would lead them right to their target – Kenley airfield. At Croydon, near Kenley, but on the other side of the railway, 111 Squadron was alerted. Twelve Hurricanes went up and were ordered to circle 100 feet above Kenley, which unit commander Squadron Leader John Thompson thought was ‘insane’. He soon had reason to change his mind – when the nine Dornier bombers broke out of the haze in the direction of Reigate. While the bombers fanned out towards the four large hangars, fuel depot and operations room, Thompson ordered his fighters out of the target area to get around behind the bombers.

The airfield’s air defences hastily launched their PAC – ‘Parachute and Cable’, a countermeasure against low-level attacks consisting of a 500-foot steel cable that was fired up to its full length in the air and then sank down under a parachute. The nine bombers flew straight into the maze of steel cables that popped up like a snake-charmer’s snakes in front of them, and dropped their bombs. Chaos broke out on the ground and in the air. Oberleutnant Rudolf Lamberty, the pilot of Roth’s ‘F1+ DT’, had no chance to turn away but ran into one of the wires. Anti-aircraft machine guns also opened fire furiously, hitting Roth’s plane and setting it on fire. The entire crew survived – albeit as prisoners of war. The crew of ‘F1+HT’ were not that lucky; it perished when their plane crashed in a field just outside the airfield. Oberleutnant Magin, the pilot of another Do 17 from 9./KG 76, collapsed in his seat mortally wounded and involuntarily pushed the control column forward. His observer, Oberfeldwebel Wilhelm Friedrich Illg, threw himself forward and grabbed the control column, and at the last moment succeeded – just ten metres above the ground – in pulling the plane out of its dive. In addition, according to the German report, he succeeded in dropping the remaining eight bombs.

While bomb explosions spread across Kenley airfield, Squadron Leader Thompson’s Hurricanes got themselves into attack position behind the remaining Dorniers, which attempted to climb away to the right, where they hoped to meet their own fighters. Several of the German bombers were damaged by collisions with PAC wires or by gunfire from the ground, and now they met the RAF pilots’ fury. But it was no easy fight for 111 Squadron, which lost three Hurricanes to the Dornier gunner’s fire.

On the other hand, not one of the Dorniers of 9./KG 76 escaped being hit by British fire. Two crashed into the Channel and two others crashed on the French coast with dead or wounded crew members onboard. Miraculously, it was the Do 17 manned by Oberfeldwebel Illg on this his first flight that fared best. Illg even managed to bring the aircraft and crew back to France, to Norrent-Fontes airfield! For this feat he was awarded the Knight’s Cross.

By then a gigantic air battle had developed over a large area south of London. At 6,500 metres altitude No. 615 Squadron, which had also been ordered to Kenley, clashed with the Bf 109s of III./JG 3, which had joined Schöpfel’s unit on a fighter sweep. Four Hurricanes and a Bf 109 fell to the ground like flaming torches. Two thousand metres below I. and II./KG 76 came in with twenty-seven ‘fresh’ Do 17s and twelve Ju 88s to finish the planned annihilation of Kenley sector station. This was the fomation that should have carried out their attack before Roth’s group. Now they were met by an alerted and vindictive British fighter force. A gigantic cloud of smoke, visible for miles around, rose from the devastation of the Kenley station, and this spurred the British pilots to fight with even greater determination.

Twelve Hurricane pilots from 32 Squadron were already present in the air above the airfield. This unit was now led by Michael Crossley, promoted to Squadron Leader, who had, in the last few days, trained his pilots for frontal attacks. Now it was time for a baptism by fire! ‘Tally Ho!’ shouted ‘Red Knight’ Crossley over the radio and the dozen Hurricanes turned on a collision course with the twin-engined Luftwaffe planes.

Twenty Bf 110s from ZG 26 had been assigned as close escort to these Dornier planes, and the Zerstörer airmen turned and dived to attack the first formation of Hurricanes from behind. ‘Flight Lieutenant [Humphrey] “Humph” Russell [of 32 Squadron] was surprised to be hit by extremely accurate and concentrated return fire from the Bf 110s and was forced to bale out over Edenbridge wounded in the left arm and right leg. First blood to the Zerstörer!’

But because they flew with the bombers, the Bf 110s were far too slow, and when they attempted to get speed up by diving, they also ended up at a height disadvantage. At that moment eight of 64 Squadron’s Spitfires plummeted from 7,000 metres, straight towards the Zerstörers. Squadron Leader Aeneas MacDonell hit the Bf 110 flown by Oberleutnant Rüdiger Proske, adjutant of I./ZG 26, and the pilot and the radio operator had to bail out. While they drifted down to imminent captivity under their parachutes, the German formation dispersed as the terrified bomber pilots swerved to avoid fighter attacks. Their bombs were scattered widely and caused no great harm.

The Dorniers and Junkers then fled back towards the coast as fast as they could. For the airmen in the Bf 110 fighters, who were forced to stay close to the bombers, it became a frustratingly slow journey back over hostile territory – while they were easy targets for the nimble Spitfire and Hurricane fighters which constantly harrased them from above. Several fresh British fighter units joined the combat. The German return track soon became marked by the wreckages of crashed Bf 110s, Do 17s and Ju 88s.

Even Flight Lieutenant Robert Stanford Tuck – who belonged to 92 Squadron, which was not in the front line – joined the battle. He was temporarily visiting Northolt airfield and, without waiting for orders, took off alone as soon as he heard about the severe fighting. Tuck, with 11 kills on his tally, pursued two German aircraft over the sea. Tuck identified them as Do 17s or Ju 88s, but it is more likely that they were a couple of fleeing Bf 110s. One of them may have been the plane flown by Oberleutnant Hans-Jürgen Kirchhoff, head of 3./ZG 26. He was killed along with his radio operator when they crashed into the sea. After a long chase, Tuck managed to shoot down one of the German aircraft into the water, but immediately afterwards Tuck’s own Spitfire was hit by cannon fire. Judging by Tuck’s own description, it seems that he was attacked from behind by another Bf 110 – which he never saw. Tuck abandoned his burning Spitfire and bailed out over land.

The sixty He 111s from KG 1 were meanwhile lucky to avoid serious fighter attacks. ‘We flew zig-zagging with the He 111s’, said Major Mettig from JG 54. ‘Because of their bad formation flight, the He 111 formation became widely scattered. I estimate the distance to 35 km between the first and the last airplane. We knew that the British would concentrate their attacks against stragglers, so this placed great demands on us in the fighter escort. By the time we reached the target, the fuel reserve allowed us no more than ten minutes to spare. But we were replaced by two other Jagdgeschwaders and then flew straight back to our bases, where many landed with standing propellers.’

The attack against Biggin Hill became a total failure. All that was accomplished was a small number of bomb craters and some unexploded bombs on the runways.

Sometime after two o’clock the fighting died down. It had caused terrible losses on both sides. The German had lost 22 aircraft – nine Do 17s from KG 76, one He 111 from KG 1, eight Bf 110s and four Bf 109s. In return, their fighter pilots claimed to have shot down 34 British planes – of which ZG 26 ‘Horst Wessel’ took half. The difference in results between Messerschmitts on close escort and those who had been out free hunting was striking. 6./ZG 26, which flew as close escort, suffered half of the eight Zerstörer losses. Three more had been shot down from I./ZG 26, which had also been tied to the bombers in this way. In contrast, Major Johannes Schalk’s III./ZG 26 – which was free hunting – was the Messerschmitt Gruppe which succeeded best during this mission – 15 victories against one own loss. Oberleutnant Sophus Baagoe from 8./ZG 26 contributed two victories and thereby increased his total to nine. But the most successful German fighter pilot on this mission was clearly Oberleutnant Gerhard Schöpfel from III./JG 26, who had knocked down four.

The German victory claims were exaggerated, but the British units had still suffered severe attrition. A total of 16 Spitfires and Hurricanes were shot down and completely destroyed, and another nine were so badly damaged that they were out of action for some time to come. Worst affected however was Kenley sector station, where ten hangars and the Operations Room were in ruins, and all telephone lines were broken. For the first time the Germans had managed to neutralise one of Fighter Command’s nine ‘nerve centres’. In addition 17 British planes had been knocked out on the ground.

At half past two I./JG 52 made a new low-level attack against Manston airfield, similar to the attack the unit had made with such success two days before. The War Diary of I./JG 52 reads: ‘A radio message was intercepted, revealing that a fighter unit had landed at Manston to refuel. This time too, we carried out the attack with great success. 10-11 Spitfires, three Bristol Blenheims and a hangar were seriously damaged or set burning.’ According to British records, two of 266 Squadron’s Spitfires were completely destroyed on the ground at Manston.

The next blow was dealt by Luftflotte 3. Twenty-five Ju 88s from I. and II./KG 54 ‘Totenkopf’ subjected the naval air base in Gosport to a devastating new attack. They were escorted by eighteen Bf 110s from ZG 76, and all German aircraft returned safe and sound to their bases. The main force of Ju 87s attacked the airfield at Thorney Island and Poling radar station further east, but there things went quite differently.

10 and 11 Group sent up five squadrons against the Stuka formations and their fighter escorts. Although the 85 Ju 87s from StG 77 had been given virtually the entire strength of Bf 109s at Jafü 3’s disposal – more than 200 Bf 109s from JG 2, JG 27 and JG 53 – and thus were many times stronger than the relatively limited number of RAF fighters, the British succeeded in tearing the Stuka formations to pieces. Twelve Hurricanes from 43 Squadron were the first ones there and attacked the Stukas just as they pulled out of their dives after dropping their bombs. From their position 5,000 metres higher the Bf 109 pilots saw how suddenly one Ju 87 after another erupted in flames far below them. When they, shocked, dived as fast as they could to rescue their protectees, they were themselves attacked.

Shouting wildly, No. 234 Squadron’s Spitfire pilots threw themselves into the mass of Bf 109s and created utter confusion among them. Flying Officer Paterson Clarence Hughes shot down two of the German fighters. So did Sergeant Alan Harker, and other ‘109s were downed by Pilot Officers Robert Doe and Edward Mortimer-Rose. Most of the Messerschmitt pilots were forced to fight to save themselves, and meanwhile even 152, 601 and 602 squadrons appeared to complete the massacre of the Stukas.

In the space of a few minutes, the British fighter pilots shot down 16 Stukas. No. 43 Squadron was credited with 8 downed Ju 87s, 152 Squadron was credited with 9, and 601 and 602 Squadron, 6 each. Sergeant James Hallowes from 43 Squadron once again shot down three Ju 87s – thus repeating his feat from 16 August – and reached a combined total of 16 victories. In 601 Squadron Flight Lieutenant Carl Davis and Flying Officer Tom Grier were credited with two victories each in the Stuka massacre. In addition, Davis shot down one of the Bf 109s which had managed to escape 234 Squadron and was trying to rescue the embattled Stukas.

In addition to the 16 Ju 87s which remained in England, two more crashed on their return to France because of severe battle damage. Among the missing crew members was Hauptmann Herbert Meisel, commander of I./StG 77. It was an unmitigated disaster for Stukageschwader 77, which was immediately withdrawn from combat. The scattered and disordered remnants of the fighter escort returned to base at irregular intervals with utterly demoralised pilots. Their unit commanders were completely unable to explain what had happened. They themselves had lost 8 Bf 109s – in combat with an enemy where they had not only had the advantage of height but also a fourfold superiority in numbers! It was a first class defeat.

The price of this amazing success to the participating RAF formations was confined to three destroyed and eight damaged aircraft. The only drawback for the British was that two pilots of 601 Squadron had been killed, and that 43 Squadron’s top ace, Flight Lieutenant Frank Carey (11½ victories), was badly wounded.

Air fighting on 18 August ended that evening when Kesselring sent a hundred or so bombers and more than 150 fighters across the Channel.

58 Do 17s from I. and II./KG 2, with a close escort consisting of 25 Bf 109s from III./JG 51, had factories and railway stations on the outskirts of London as their main objectives. North Weald airfield was the target for 51 He 111s from II. and III./KG 53, with 20 Bf 110s from I. and II./ZG 26 as close escort.

A hundred Bf 109s from all the Jagdgeschwaders in Luftflotte 2 went out free hunting ahead of them. Once again the Bf 110s from III./ZG 26 flew on free hunting. No less than 143 Spitfires and Hurricanes went up to repel the invaders. Even Wing Commander Victor Beamish, the almost forty-year-old commander of North Weald sector-airfield, took off with one of the 151 Squadron Hurricanes. The Irishman Beamish was a fierce fighter. ‘We have to kill all the Germans in the air’, he said.

In a cruel repeat of the previous day’s mission, 4./ZG 26 – which was the close escort for KG 53 – bore the brunt of the British fighter attack. ‘We had strict orders to fly close escort, and that was the cause of the disaster that followed’, said Unteroffizier Theo Rutter, rear-gunner of one of the Bf 110s downed in the air combat. This Staffel was attacked by at least three squadrons, and of four Zerstörers that were lost during the mission, three belonged to 4./ZG 26. The German Bf 109 units fared little better. III./JG 51 was admittedly credited with three victories and no own losses. Hauptmann Walter Oesau accounted for two of these and this raised his personal score to twenty. But three Bf 109 aces were lost in the engagement, and in all cases Polish airmen were involved. II./JG 51 lost two Bf 109s without managing to shoot down a single British plane (at least none that was confirmed). Pilot Officer Pawel Zenker, a Polish pilot in 501 Squadron, explained how he shot down Hauptmann Horst Tietzen, the ace with 20 victories who commanded 5./JG 51: ‘With Green 1 I went straight to the fighters and engaged one of them. He turned back towards France and I chased him as he climbed firing from 300 [feet] and closer ranges and about 10 miles over the sea I saw smoke and fire come from the fuselage and he rapidly lost height. The Me 109 did not adopt evasive action but flew straight on until it crashed into the water somewhere near the North Goodwin Lightship.’ Tietzen’s dead body later washed ashore near Calais. Flying Officer Stefan Witorzenc, another Pole in 501 Squadron, shot down another of the pilots of 5./JG 51, Leutnant Hans-Otto Lessing, who was killed.

III./JG 26 was credited with two victories – which was slight consolation for the loss of two of the unit’s most important aces: Leutnant Gerhard Müller-Dühe dived to attack a Hurricane, eager to record his sixth victory. It was a mistake that would cost him dearly. Peter Brothers, who then served as a Pilot Officer in 32 Squadron, explained what happened: ‘I turned sharply right, on to the tail of an Me 109 as he overtook me. I gave a quick glance behind to ensure that there was not another one on my tail, laid my sight on him and fired a short burst. I hit him, another short burst and he caught fire and his dive steepened. I followed him down, he went into a field at a steep angle and a cloud of flame and black smoke erupted.’

By all accounts Müller-Dühe was then fired upon by the Polish Pilot Officer Boleslaw Wlasnowolski, who described how he followed the Bf 109 down towards the ground: ‘I followed, firing several short bursts, he dived into the ground and went up in flames.’

Müller-Dühe did not survive. His comrade from III./JG 26, Leutnant Walter Blume – also credited with five victories – had slightly better luck. Blume had a Hurricane in his sights when suddenly a tracer passing his cockpit made him look upwards and back. To his horror he found that he was staring right into the eight fire-spitting muzzles of a diving Hurricane. Blume turned as he dived, but could not get away from the Hurricane pilot – 32 Squadron’s Pilot Officer Karol Pniak. The latter’s commander, Squadron Leader Michael Crossley, and Pilot Officer Alan Eckford also raced after Blumes steeply diving Messerschmitt 109. Blume crash landed his 109 near Canterbury; he was seriously injured, but was still alive.

Despite the mediocre performance of the Bf 109s only four German bombers were shot down – all from KG 53. This was mainly due to the free hunting Bf 110s from ZG 26 ‘Horst Wessel’. They accounted for most of the 12 British fighters shot down in this combat – nine of which were completely destroyed. When Squadron Leader Peter Townsend intervened with 13 Hurricanes from his 85 Squadron, he found that the Bf 110s made it almost impossible to reach the bombers. ‘A general engagement was now taking place, enemy aircraft consisting chiefly of Me 110s’, said Townsend. Among the British pilots shot down by Bf 110s was Squadron Leader Gordon, commander of No. 151 Squadron. It was the second time in three days he had been shot down, but this time Gordon was badly burned. Another RAF pilot to be shot down – possibly also by a pilot from III./ZG 26 – was an ace with 15 victories, albeit an unusual one. His name was Rodolphe de Hemricourt de Grunne, and he was a Belgian nobleman who had fought side by side with several Luftwaffe veterans as a volunteer fighter pilot in Franco’s Air Force during the Spanish Civil War. There he had been credited with 14 victories. Now, he served as a pilot officer with 32 Squadron. Badly burned, Count de Hemricourt de Grunne bailed out of his blazing Hurricane and spent six months in hospital.

Even Wing Commander Beamish came close to being shot down, but was fortunate to escape with his Hurricane badly damaged. When Flight Lieutenant George Stoney was shot down and killed by a Bf 110 over the Thames estuary at 18:45 (German time), 501 Squadron had lost six Hurricanes and four pilots during the day.

Upon its return to France, Oberleutnant Theodor Rossiwall’s 5./ZG 26 – which had been free hunting with III./ZG 26 – counted four victories without own losses. Major Johannes Schalk’s III./ZG 26 ‘Horst Wessel’ was as usual the most successful, with 11 new victories – this time without any own losses. In Oberleutnant Ernst Matthes’ 7./ZG 26, Leutnant Kuno Konopka and Feldwebel Franz Sander were credited with two victories each; in the latter case it was the pilot’s third victory that day. With the Spitfire Oberfeldwebel Joseph Bracun reported shot down at 18:58, 7./ZG 26 reached its 30th victory – achieved against only one own combat loss since the war had started.

Typically, both sides proclaimed themselves as victors in the air battles on 18 August. Fighter Command reported 126 German aircraft downed. Of these, 54 Squadron claimed 14, with no own losses. That evening 54 Squadron received a telegram from Lord Newall, Chief of the Air Staff: ‘Well done 54 Squadron. In your hard fighting this is the way to deal with the enemy.’

The German High Command announced that 124 British aircraft had been shot down. With 51 victories ZG 26 ‘Horst Wessel’ claimed the lion’s share of this result, which gained the unit a special mention in the OKW communiqué. According to German estimates the RAF had lost 732 aircraft in the previous eight days.

The actual combat losses on 18 August were 71 German aircraft and 30 fighters from Fighter Command. In addition, 10 RAF fighters crashed or emergency-landed with combat damage in England, and as many again had landed with moderate damage. For Dowding and Park the British loss figures were enough to prevent themselves from getting carried away by the victory communiqués. Without a doubt more hard air fighting that would grind down already beleaguered units lay ahead. 501 Squadron’s Operations Record Book for 18 August gives a clear picture of the pressure the fighters on both sides were under: ‘Squadron 15-mins Available from dawn to 8.30 when aircraft took off from Hawkinge. Combat near Canterbury in broken cloud and haze. P/O [Kenneth] Lee wounded in the leg, P/O [Franciszek] Kozlowski seriously injured, Sgt [Donald] McKay slight burns, P/O [John] Bland killed. Squadron returned to Gravesend. All aircraft scrambled – vectored to Biggin Hill which was under attack. P/O [Robert] Dafforn [shot down and] baled out. 7 Hurricanes took off for Hawkinge patrol at 16.50. Met 50 bombers and fighters. Red section attacked. 2 Me 110 shot down. F/L [George] Stoney killed in that combat.’

The mood was even more sombre on the German side. Göring was utterly shocked by the reports he received that night. In particular he could not understand how a relatively small force of RAF fighters had been able to beat up a mass formation of 200 Bf 109s and inflict a defeat of historic proportions on his dive-bombers. Göring had long been aware of the vulnerability of the Ju 87, and he had watched the losses among the Stuka units mount with growing concern. On 8 August, ten Ju 87s were lost, on the 13th six, on the 15th seven and on the 16th nine. But not even in his worst nightmares could the Reichsmarshall have imagined what happened on 18 August. Perhaps the worst thing was that it took place under the eyes of Jafü 3’s entire fighter force! The Luftwaffe’s total combat losses amounted to nearly 350 aircraft since large scale attacks had started on 8 August. Göring was not the only one to conclude that the air offensive against England was not going as planned. The RAF was proving a far harder nut to crack than the Germans expected.

Not only in Britain, but throughout the world, the British airmen’s stubborn fight against the vastly stronger Luftwaffe was looked on with amazement and admiration. After Poland, Norway and France people had come to regard Hitler’s new Germany as invincible, but on this tiny island, led by its irrepressible prime minister, the people continued to offer resistance. In particular this made a big impression in the USA. Winston Churchill’s speech in the British Parliament on 20 August was full of admiration for the pilots in the RAF, and some of the words he uttered have become legendary: ‘The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the World War by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few. All hearts go out to the fighter pilots, whose brilliant actions we see with our own eyes day after day.’ Then he added: ‘but we must never forget that all the time, night after night, month after month, our bomber squadrons travel far into Germany, find their targets in the darkness by the highest navigational skill, aim their attacks, often under the heaviest fire, often with serious loss, with deliberate careful discrimination, and inflict shattering blows upon the whole of the technical and war-making structure of the Nazi power.’

Only days later the British bomber pilots – whose contribution to the Battle of Britain is often underestimated – would make a vital contribution that helped change the course of the battle.