At the start of 1915, the French mounted several unsuccessful offensive operations in the Artois and Champagne, while, at the beginning of March, the BEF launched an offensive at Neuve Chapelle. The significance of Neuve Chapelle was not that it failed but that it very nearly succeeded. The problem for the BEF was converting the break-in into a breakthrough. The German defensive line consisted of only one trench line and lacked support and reserve lines, although it did include several strongpoints 1,000 yards behind the trench line. There was some wire in no-man’s-land. After an intense bombardment by 354 British guns lasting only 35 minutes, targetting the trenches, four divisions of 40,000 men from the First Army attacked along a 3,280-yard front. The artillery was supported by eighty-five Royal Flying Corps aircraft which acted as aerial spotters. This was not an innovation as aerial spotting of this kind had been tried during the Balkan Wars a few years earlier. The field guns successfully destroyed the wire but the howitzers, which were supposed to destroy the trenches and the strongpoints, failed to do any significant damage.

Taken by surprise, the Germans were overrun and, in a matter of a few hours, the British had advanced beyond the German line of strongpoints. A rigid timetable and an inflexible plan, made worse by poor communications between the advancing troops and First Army HQ, all contributed to poor control of the battle and prevented the near breakthough from being developed further. After the success of the first few hours, the advantage had been lost by the afternoon. German troops were quick to counter-attack and, within two days, the status quo had more or less been restored, the Germans having lost very little ground.

Sir John French, blamed the failure at Neuve Chapelle on the severe shortage of high-explosive shells. This shortage not only afflicted British artillery at Neuve Chapelle but the whole of the BEF during the first six or seven months of 1915, and became a national scandal when it was made public. The Shell Scandal brought down the Liberal government and led to the creation of the Ministry of Munitions in June 1915, which took over all aspects of munitions production in Britain. The shortage of shells had undoubtedly been a significant hindrance at Neuve Chapelle as the guns had been restricted to 200–400 rounds apiece, a paltry figure when later bombardments lasted for days and weeks of sustained firing. The problem highlighted the importance of artillery in deciding the outcome of battles on the Western Front. Without enough guns and without enough shells, no army could attack and expect to win. Moreover, and just as important, no army could properly defend itself or, in this case, deal effectively with counter-attacks. The intensity – although not by later standards – and the brevity of the preliminary bombardment at Neuve Chapelle wrong-footed the Germans, however, who had already come to expect a longer bombardment to precede an infantry assault. Without question the short, heavy bombardment of the trenches and line of strongpoints had been a major factor in the initial success but the fixed barrages on a strict timetable had been unhelpful. However, at that time, there was no means by which the schedule could be amended once the fire plan had been set in motion.

Despite the shortage of shells, the bombardment neutralized the Germans, thereby allowing the British infantry to seize their objectives. However, because the howitzers failed to destroy the German defences, which allowed German infantry firepower to recover from the initial shock, the British drew the conclusion that more intense and longer bombardments were necessary to secure success. The conclusion that neutralization of enemy firepower rather than destruction of his defences was the key to success was not apparent to anybody at that time. Neuve Chapelle led to an expansion of the artillery so that it became the dominant force on the battlefields of the Western Front. It was evident from French and German experience earlier in 1915 that a preliminary bombardment was essential to success. The question was whether it should be short and intense, or carried out over several days, choices that tended to made according to the number and calibre of guns available. After Neuve Chapelle, a doctrine of destruction of the enemy was adopted by the British in the belief that, not only was complete destruction possible, but the inevitable loss of surprise that came with long intense bombardments did not matter as there would be no enemy left to be surprised.

At the Battle of Festubert in May of the same year, the British adopted a policy of destruction with a bombardment that went on for two days. The loss of surprise cost the British 24,000 casualties, although the failure at Festubert was attributed to insufficient destruction of the German defences. When the British launched an offensive at Loos in September, the barrage lasted for four days but its effects were diminished by the fact that the gun density was only one every 30 yards of front engaged, whereas at Neuve Chapelle it had been one gun for every 5.5 yards. This compromise had been necessary because of the shortage of ammunition which did not allow a heavier bombardment. The ideal level of destruction of the enemy defences was not achieved. The bombardment at the start of the Somme offensive, nine months later, lasted a week and included a hitherto unprecedented number of heavy guns, as well as trench mortars. The number of guns per yard during the preliminary bombardment on the Somme was approximately twice that at Loos, while the frontage was twice as long, 25,000 yards compared with 11,200 yards. Unlike at Loos, there was no shortage of ammunition. The prolonged bombardment and the greater gun density on the Somme was intended to obliterate the wire and German resistance, and especially to destroy German machine-guns, before the infantry assault on 1 July.

At Messines, in June 1917, the preliminary bombardment lasted seventeen days as the doctrine of destruction reached its zenith. The mines fired at Messines were in accordance with this doctrine. The gun density was such that, yard for yard, there were twice as many field guns at Messines than for the preliminary bombardment on the Somme and three times as many heavy guns. On the Somme, there was one field gun for every 21 yards and one heavy for every 57 yards, whereas at Messines, there was one field gun every 10 yards and one heavy every 20 yards. Between 3 June and 10 June, the guns fired 3,258,000 rounds, nearly twice the quantity fired during the first eight days of the Somme (1,732,873 rounds). The mortars at Messines fired 800,000 rounds.

At the same time that the number of guns and quantities of ammunition were increasing in order to bring about the realization of the ideal of complete destruction of the enemy, the manner in which the bombardments were conducted and the targets engaged by the guns went through a series of fundamental changes. Such changes were driven by a need to overcome the enemy and his trench systems. The nature of defence also changed. The concept of defence in depth was created after Neuve Chapelle so that by the time of Loos, the Germans had more than one line of trenches. Had not the nature of defence changed, the search for ever greater firepower to destroy the enemy’s defences would have lacked impetus. At the same time, the increases in firepower and the increases in defensive depth drove a change in infantry tactics. By the beginning of 1916, the power of artillery was such that infantry were at its mercy, while the firepower of the infantry in defence had also increased so that attackers stood little chance if they were caught in the open, especially en masse. The purpose of the attackers’ artillery was to destroy the defenders, to enable the infantry to take their objectives. To complicate matters, the enemy artillery attempted to destroy the attacking infantry and the attackers’ artillery. While counter-battery fire had been employed before the Russo-Japanese War, it now came into its own. This was not merely a question of shooting first since weight of fire and accuracy were crucial. Accuracy was not simply making sure that the shells landed where they were intended, but it was imperative to know the location of the enemy batteries. Thus, aerial photography and mapping became essential to gunnery. Then there was the question of how the infantry should work with the artillery. This was the nature of the struggle which attackers and defenders both faced in 1915–17.

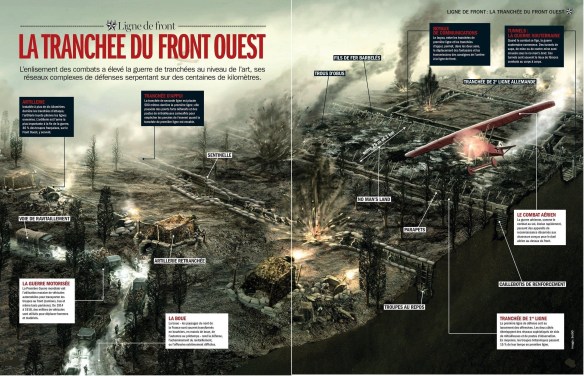

While the French and the British both concluded from the battles of 1915 that the way forward was to increase the firepower of their artillery and lengthen the preliminary bombardment phase of an offensive, the Germans took a somewhat different lesson from these battles. On the one hand, the growing power of artillery seemed to offer the German Army a way to defeat France, which ultimately led to the epic struggle at Verdun that began at the end of February 1916 and continued for ten months; while on the other, the Germans realized that a single line of trenches was not sufficient to prevent a determined Allied assault from breaking through, sweeping all before them. The solution to this problem was to build a second line of defence, similar to the first, which would contain any break-in and prevent a breakthrough. By the time the British launched their offensive at Loos in September 1915, the Germans were in the process of building this second line. And by the time of the Somme offensive in the summer of 1916, the Germans had developed their defence in depth to include a third line. When in 1917, they built the Hindenburg Line, the defensive zone was up to 15 miles deep and included five lines.

To make matters more difficult, the Germans stopped manning their front-line trenches in strength, but withdrew the bulk of their troops to what was, in effect, the second line, with only about a quarter of the infantry being located in the first two trench lines immediately facing no-man’s-land. Thus, at the start of the Somme in 1916 the German trenches closest to no-man’s-land were held very thinly and, once the preliminary bombardment started, the troops in them sheltered in deep bomb-proof dugouts, leaving very few troops to man the trenches. By 1917, the German front line was no more than a series of outposts, thinly held, located hundreds of yards in front of the main line of defence. At the same time, the development of strongpoints with all round defence began to replace linear defensive lines of continuous trenches, a process of change that led to the construction of the Hindenburg Line. Here, the defensive lines were more in the nature of zones than linear trench lines of the sort commonly employed in 1915. In conjunction with the dissolving of rigid lines of defence, the Germans adopted an elastic defence in which the immediate counter-attack to retake any ground lost played a major role.

The tactics employed by the infantry went through a similar process of change. While the infantry tactics of the assault employed in the early battles of 1915 tended to be based on pre-war tactics, so that infantry engaged infantry and artillery provided support, this was soon found to be costly and ineffective. Nevertheless, the notion of attacking in lines or waves persisted well into 1916, largely because of the relationship between the infantry and artillery, whereby the artillery timetable dictated how the infantry attacked. The growing dominance of artillery placed restraints on the infantry because of the nature of artillery barrages. The barrage was intended to support the infantry by preventing the enemy from engaging the assault troops as they approached. However, it forced a rigid timetable on the infantry and took no account of obstacles that might have to be overcome which slowed the advance. Equally, the assault troops had to contend with enemy fire and as his firepower increased so the likelihood of their crossing no-man’s-land unscathed to engage the enemy on his territory diminished. Thus, while linear tactics favoured reasonable coordination between the attackers’ artillery and their assault troops, it also favoured the enemy as linear waves presented unmissable targets, especially when the enemy was able to enfilade the attacking waves. Far from being a straightforward problem that might offer a straightforward solution, a quite different approach to infantry assaults was required.

The idea of doing away with rigid linear tactics and adopting a more flexible approach was considered as early as May 1915, when Captain André Laffargue devised tactics of infiltration which avoided the massed frontal assault. These were derived from his own experience and were a variation on the wave theme. No one took much notice of his theories. At much the same time, and quite independently, Major Wilhelm Rohr, who commanded the German Army’s Assault Detachment, also devised tactics of infiltration. The purpose of the Detachment was to develop new tactics for offensive operations. Rohr and his unit tried the new tactics against the French in the Vogues before using them at Verdun. Rohr and the Assault Detachment, renamed Assault Battalion Rohr in April 1916, were the first Stormtroopers.

The artillery barrage, as distinct from the bombardment that preceded an infantry assault, was intended to help the assault by preventing the enemy infantry from bringing their weapons to bear on the attackers. Counter-battery fire, on the other hand, was purely a duel between the guns, a duel which the Germans increasingly lost from about 1917 because the Allies, and the British in particular, could bring a heavier weight of fire to bear. It was clear from early 1916 that artillery had become the dominant force on the battlefield, and battles were won or lost according to how the artillery was used, or, at least, the casualty level was decided on how well the artillery could deal with the enemy. Indeed, when the Australians attacked Pozières during the Somme campaign and did so without a preliminary bombardment, they suffered very high casualties and failed to take their objectives because of German firepower, both from infantry in the trenches and from artillery. The protective barrage in support of an assault was not an alternative to a preliminary bombardment, of course. The problem was how to hit the enemy trenches while the infantry advanced without causing friendly casualties in the process.

The first barrages were no more than lines of bombardment across the width of the battlefield, targeting the front-line trenches. After a fixed time interval, it moved on a somewhat arbitrary distance to lay down another line of shelling beyond the advancing infantry but not necessarily on the next line of trenches. The straight barrage was of very limited help to the infantry who were often left behind by the advancing barrage. The next development was the lifting barrage, first used by the French in early 1915 in the battles in the Artois and Champagne. The barrage still advanced in the same way as the straight barrage but it hit trenches each time it lifted to the next target. By now, the infantry were accompanied by Forward Observation Officers whose job it was to direct the artillery to improve its shooting. In both cases, the artillery employed indirect fire and one of the problems this highlighted was the difficulty of accurately locating the targets due to a lack of reliable maps. Shooting by the map with accuracy was more of an aspiration than an achievable goal before the middle of 1916. Unfortunately for the infantry, the lifting barrage was no easier to follow than the straight barrage. The added disadvantage was the necessity for the guns to fire registration rounds beforehand to ensure that they had the range of the target. In registering the guns, the enemy was, of course, alerted to the targets that were about to be hit and, indeed, to the fact that an offensive was likely in the near future. Suspicions were increased if a lot of guns were firing registration shots. They were easy to identity because of their apparent randomness, although they bracketed what was clearly a target. It was because of this easy identification of registrations that trench mortars hid theirs during an artillery bombardment.

Although the preliminary bombardment also gave away the fact that an offensive was starting, prior registration of the guns was insignificant to overall lack of surprise. Any bombardment that lasted more than a few hours gave the enemy time to move his infantry and his guns. By 1917, greater effort was made to conceal registration shots so that the targets were less likely to be identified by the enemy. With this in mind, every effort was made to conceal the location of gun batteries to avoid counter-battery fire. They were sited on reverse slopes and some batteries remained inactive so that they remained hidden until the moment they opened fire for the offensive.

In 1916, the so-called piled-up barrage was introduced to satisfy the infantry’s need for a barrage that focused on the trace of the enemy trenches. Whereas the earlier barrages moved forward in lines parallel with the gun line and passed over the enemy trenches in the same straight line irrespective of the trace of those trenches, the piled-up barrage concentrated or piled up as it hit the enemy trenches, until the rest of the barrage had caught up, thereby concentrating the fire on the trenches. This ensured that the entire trace was hit simultaneously, which had not been possible with straight-line barrages. Both the straight and lifting barrages had allowed the enemy in those parts of the trench that were ahead of the advancing barrage line to enfilade the infantry to their left or right. The piled-up barrage overcame this problem. However, to be effective, the full extent of the enemy disposition needed to be identified beforehand. Trench raiding and patrolling helped in this respect but there was no foolproof way to locate all the enemy’s trenches or to determine the strength with which he held the various sections. There was also the disadvantage that the attacking infantry had to assault the trenches simultaneously, irrespective of the location of the trenches. In practical terms, this meant that those troops which had the furthest to go to hit the enemy trench allocated to them had to leave their own trenches before those troops which had a short distance to cover. This made them vulnerable to enemy fire.

The creeping barrage was a solution to the problems posed by the piled-up barrage. Now, instead of the barrage moving forward parallel with the gun line, it was parallel with the enemy trench line. For the first time, it was possible for the assaulting infantry to hit the enemy trenches immediately after the barrage had passed over these trenches. To achieve this, the infantry still had to leave their trenches according to their distance from the enemy so that they all hit the enemy, irrespective of the trace of his trenches, at the same time. Unlike with the piled-up barrage, the infantry did not have to wait until the entire enemy line was under the barrage before leaving their trenches, although in practice they had left their trenches before then, but had to slow their advance or speed it up according to the distance between them and their targets. Good planning and execution were necessary with every type of barrage. And in every instance, the infantry had to advance as close to the exploding shells as they could safely get. Hence, rehearsals on ground that replicated the enemy line were carried out before the offensive, although this was not done with live shells.

Until about the middle of 1916, the infantry assault was a linear operation in that it consisted of lines, or waves, of men with specified time intervals between each line, each of which was straight irrespective of the trace of the enemy trenches. The first day of the Battle of the Somme has been made infamous by the fact that the British troops approached the German trenches in straight-line waves. While the idea of infiltrating groups of men was considered, the plan was not taken up. It has passed into folk lore that the reason for this was the lack of faith of the generals in the troops of the New Armies to execute anything but simple manoeuvres on the battlefield, with infiltration and group tactics being considered too sophisticated for their abilities. However, not only is this view of the relationship between British generals and the New Armies quite unfounded, but the reason for using linear wave tactics had nothing to do with any supposed lack of ability on the part of the citizen soldier of Britain’s New Armies. The linear nature of artillery tactics at that time precluded an alternative to linear infantry tactics. To have attempted to employ non-linear infantry tactics would have required a highly complex artillery plan. Moreover, there was a real fear among the planners of the Somme offensive that localizing concentrations of artillery firepower, which nonlinear infantry tactics would require, could lead to sections of the German trenches, and machine-guns in particular, being missed by the barrage. One advantage of the linear barrage was that the whole of the hostile territory was eventually swept by fire so that everything was subjected to shelling before the infantry reached the trenches. To this end, there was one 18-pounder for every 25–30 yards and one howitzer or heavy gun for every 65 yards.

The infantry wave tactic would have been successful had the artillery been able to destroy or neutralize all the enemy machine-guns, some of which were positioned in shell holes in no-man’s-land, as well as between the trench lines, but the artillery had been unable to do this. So long as the waves moved forward according to the timetable in the plan, they could keep up with the barrage. In some areas of the front, the lifts were short enough for a creeping barrage to be created. This was as much a function of the accuracy and precision of the guns as it was a deliberate intention to creep the barrage forwards. But as soon as the leading wave was held up by more resistance than anticipated, such as machine-guns or surviving enemy infantry, the whole assault scheme ran the risk of descending into chaos as each successive wave ran into the back of the preceding wave. For the plan to function smoothly, the timetable had to be followed, which was governed by the artillery lifts and the resistance of the enemy. Had the artillery had the technical sophistication to achieve a precise piled-up barrage rather than an imprecise approximation of one, the effect on the German trenches would have been much more destructive. To achieve a precise piled-up barrage, precise gunnery was needed but, at the time of the Somme, such precision was not technically feasible.

The rise in importance of counter-battery fire meant that more heavy guns were allocated to this role than to infantry support, which hindered the weight of fire in the preliminary bombardment and in the supporting barrages. The Germans discovered in 1915 from their experience on the Eastern Front that surprise and weight of fire were more important to success than bombardments which might last for up to a week. Indeed, contrary to the Allied practice of prolonging bombardments and increasing the weight of fire, the Germans increased their weight of fire but decreased the duration of the bombardment. Whereas the Allies bombarded the Germans on the Somme for a week and the British shelled the Germans at Messines in 1917 for a week, the Germans fired a preliminary bombardment on the French at Verdun for only 10 hours. On 21 March 1918, at the start of the German Michael offensive, the assault was preceded by a bombardment of only 5 hours in which 6,473 guns and 3,532 trench mortars fired millions of shells, including more than 2 million gas shells. German artillery outnumbered British guns by more than 2.5 to 1.

This highlighted the different philosophies of destruction and neutralization. While the Allies had gone down the total destruction road, the Germans had opted for neutralization and had developed their infantry assault tactics accordingly. At the same time, they adapted their defensive policy to reflect the same principals. As the Allies tried ever harder to destroy the German lines before an assault in 1917, so the Germans withdrew the bulk of their infantry and artillery from the forward zones at the start of an Allied offensive, shelled the British trenches when they calculated the assault was about to start, withdrew again and shelled their former positions when the Allies were in possession. Reserves were kept out of artillery range, approximately 5.5 miles to the rear but still within the defence zone. By extending their defence zone the Germans diluted the effect of Allied destruction tactics. They developed island strongpoints each of which was located to take advantage of local topography and road links and sited so that each strongpoint could act cooperatively with its neighbours, thereby creating lethal zones through which attacking infantry would have to pass. And always the Germans used the immediate counter-attack, with ad hoc formations of troops when necessary, to deal with any loss of ground. The notion of linear assault tactics and barrages were made redundant by such defensive measures.

Destruction tactics were applied by the British with ever greater intensity at Vimy Ridge, Messines and Passchendaele. While Vimy and Messines were both limited actions, Third Ypres was a major offensive and, while the limited actions achieved limited successes, Third Ypres became a costly battle of attrition in atrocious conditions which, in terms of its original objectives, was far from a success. At Passchendaele, the tactic of destruction was at last shown to be counter-productive.

The last British offensive of 1917, Cambrai, marked a radical departure from previous artillery and assault tactics. Not only were tactics of neutralization employed by the artillery, but Cambrai saw the first use of massed tank assaults in support of the infantry. The tank had been devised independently by British and French engineers during 1915 and 1916, as a solution to the trench deadlock. British tanks first saw action during the later stages of the Somme battles in September 1916. The French first used theirs in April 1917 during the disastrous Chemin des Dames offensive. Neither debut was a success, however, and their achievements, such as they were, were modest. From the outset, tanks were under-gunned, under-armoured, under-powered and mechanically unreliable, while they were quite unsuited to crossing the shell-cratered landscape of the Western Front as they easily stuck in craters and trenches, tended to throw a track on rough ground and sank in mud. Indeed, their unreliability was the biggest cause of operational losses; more tanks broke down or were ditched than were knocked out by enemy action. At Cambria, 378 tanks started out from the start line on the first day of the offensive and, although some tanks remained in continuous action for 16 hours, no fewer than 114 were lost through mechanical failure and ditching, while sixty-five were knocked out by enemy action.

Cambrai also saw the use of aircraft in an air-support role to suppress the enemy’s ability to fight, an operational innovation pioneered by Lieutenant Colonel J.F.C. Fuller, one of the advocates of tank warfare. Moreover, there was an emphasis on air observation for communicating the fall of shot to the artillery batteries. The artillery did not fire registration shots before the battle so that complete surprise was possible. Instead, gunners used predicted fire for counter-battery work. Although predicted fire had been tried before, it was not until late 1917 that it could be relied upon as an effective means by which to hit enemy batteries. Predicted fire was a science, not an art, which combined the technical skills of several disciplines to ensure that the target was hit precisely. Not least among these was map-making. Without accurate maps, no amount of clever gunnery was ever going to result in the intended target being hit except by chance. To this end, thousands of aerial photographs were taken by reconnaissance aircraft flying over enemy-held territory, in support of which fighter aircraft flew escort patrols to prevent enemy aircraft shooting down the reconnaissance planes. From these photographs, accurate maps were prepared and regularly updated using new photographs by the map-making branch at GHQ.

Fundamental to accurate gunnery was an understanding of the science of ballistics. Aspects of this included the weight of the shell, muzzle velocity and the effect of barrel wear on range and accuracy. Such issues applied specifically, not to the artillery in general or to a battery, but to individual guns. Since 1915, gunners had become aware that the rifling in a barrel was worn down by each shot fired and that, as barrels became worn, so accuracy and range diminished. Indeed, shooting from very worn barrels could result in shells landing unpredictably on friendly troops. By the end of 1917, gunners were able to factor all this into their calculations, for each gun, along with the wind speed and direction as well as the air temperature to ensure that the first shot fired from each gun would have a very high probability of hitting the target. Thus, the need to fire registration shots became redundant and tactical and strategic surprise were once more realistic possibilities. Cambrai was the first opportunity for British gunners to put all this into practice. The object at Cambrai was not to destroy the Germans in a prolonged artillery bombardment, like those of the past, but to prevent the enemy from engaging the British artillery, tanks and infantry. In other words, the object was to neutralize the enemy’s ability to fight. With this in mind, smoke and tear gas rounds were fired in addition to high explosive, while the tanks created corridors through the wire obstacles for the infantry and acted as mobile artillery to deal with pillboxes and strongpoints. There was no preliminary bombardment. When zero hour arrived, a creeping barrage from more than 1,000 guns led the way and the tanks and infantry moved forward, 300 yards behind the barrage.

The Germans were completely surprised and overwhelmed. The assault broke into the German line and penetrated to a depth of 5 miles on a 6-mile front in 10 hours, by which time tank crews and infantry were exhausted. Tanks outran their infantry, despite their slow speed. There were no tank reserves so that by the third day there were, in effect, no tanks in action. The initial success could not be exploited and when the Germans counter-attacked ten days after the start of the battle, the advantage had passed to them. The British lost most of the ground they had taken but more importantly they had been stopped from converting the break-in into breakthrough.

During the Cambrai counter-attack, the Germans applied infiltration techniques and used them again in their spring offensives of 1918. At the same time, they applied more flexible artillery tactics that, like the Allied artillery, now no longer focused on destruction, but on neutralization. The object was not so much suppression of the ability of the enemy’s ability to fight, as destruction of their morale by subjecting them to a sudden and very intense bombardment of short duration, followed by an immediate infantry assault. Such artillery tactics were devised by an artillery commander, Lieutenant Colonel Bruchmüller, who tried them out on the Eastern Front before applying them to the Western Front. The Germans also used predicted fire without registration. The new artillery tactics were combined with infantry tactics which emphasized infiltration, as well as fire and movement, and both were integrated in a strategy which sought to apply a heavyweight punch on a short sector of front to achieve a breakthrough. Such tactics were named after General von Hutier who first applied them at Riga on the Eastern Front in September 1917. Part of this overall attack plan included so-called stormtroop tactics which were aggressively applied in the assault phase by elite units of stormtroopers, leaving more conventional troops to deal with pockets of resistance bypassed by the stormtroopers. This was how the spring offensives of 1918 were mounted.