Much remained to be done. Two 9000 ft paved runways had been planned for Isley Field, but when Hansell arrived only one had been paved to 6000 ft, and there were no hardstandings or buildings. Nevertheless, by November 22 over 100 aircraft had flown to Saipan directly from their training bases. Target priority had been switched from steel to one offering more immediate results, the Japanese aircraft industry. This was to be accomplished by high-level daylight precision bombing, the goal still fervently sought by the United States’ senior air commanders. However, the problems encountered on a series of ‘shakedown’ raids at the end of October forced Hansell to the conclusion that 73rd BW’s crews were too inexperienced for this method of attack. The bulk of the Wing’s training had focussed on blind bombing with the use of radar, which allowed crews a certain latitude in choosing attack altitudes and bombing runs. Through no fault of their own, the crews lacked the expertise for high-level formation flying. Poor results obtained in raids on targets in Truk were aggravated by the recurrence of engine problems and Japanese air strikes on the Saipan field launched from Iwo Jima. The Chengtu pattern was unfolding in the Marianas and as it did the autonomous future of Arnold’s B-29s was placed in jeopardy.

On November 24 111 B-29s flew from Saipan to attack the Nakajima Aircraft Company’s Musashi plant, on the outskirts of Tokyo, which produced approximately 30 per cent of the Japanese air forces’ engines. Engine failures forced 17 B-29s to turn back, and as the remainder approached the home islands at altitudes of 27 000-32 000 ft they encountered the Jetstream. During the winter months this powerful wind blew out of the west at precisely the altitudes flown by the B-29s. Plucked up like leaves in a gale, the aircraft attained speeds of up to 450 mph as formations disintegrated and bombing became a matter of guesswork. Cloud obscured the target and the majority of the B-29s dropped their bombs at random over the Tokyo area. One of the B-29s was rammed and destroyed by a Japanese fighter. In ten subsequent raids on the Musashi plant, a mere two per cent of the bombs dropped hit any of the complex’s buildings; only ten per cent of the overall damage caused fell within the 130 acres occupied by the plant. In 11 raids on this resilient target, 40 bombers had been lost, while Japanese casualties in the plant were about half the figure of 440 airmen who had failed to return.

The Musashi plant was a tough nut to crack, but the B-29’s failure to punch its weight was graphically illustrated early in February 1945 when US Navy fighters and bombers from Vice-Admiral Marc A Mitscher’s Task Force 58 caused more damage to the Musashi plant than the combined B-29 raids. 73rd Bombardment Wing’s second principal target had been the Mitsubishi engine plant at Nagoya, 17 per cent of which was destroyed in raids during the course of December, although at disquieting cost. The average loss of five aircraft – or 55 crew – a mission was placing a heavy strain on the Wing’s ability to sustain the offensive. By mid-January the mission abort rate was running at 23 per cent, another cause for concern. The principal reason was overloading of the B-29s. Removal of one of the fuel tanks in the bomb bay and a reduction in the amount of ammunition carried saved over 6000 pounds in each aircraft. Performance rose dramatically. With an improved maintenance system, individual engine life was stretched from 220 to 750 hours.

Once again LeMay was brought in as the ‘fireman’, assuming command of XXI BC at the end of January 1945. His appointment coincided with a considerable expansion of the Command, marked by the arrival of 313th BW under Brigadier-General John H Davies. His wing was based at the North Field, Tinian, the largest bomber field ever built, which boasted four parallel 8500 ft runways.

In November 1944, General Arnold had received a report on the structure of the Japanese war economy. It indicated that production in Japan tended to be dispersed in numerous small businesses, and suggested that as there was a high proportion of wooden buildings in Japanese cities, area incendiary attacks might be up to five times more effective than precision bombing. The acceptance of these conclusions marked a crucial turning point in American bombing policy. From November 1944, the B-29s had been striking at precise economic targets, which nevertheless involved a degree of indiscriminate destruction. They were now about to launch a general urban bombing offensive aimed at demoralizing the population and taking advantage of the particular vulnerability of the Japanese cities to incendiary raids. The fate which had overtaken Lübeck, Hamburg, Darmstadt and Dresden was about to overwhelm the cities of Japan.

On January 3 4900-pound incendiary clusters were used in a raid on Nagoya, and on February 3 160 tons of incendiaries were dropped by 313th and 73rd Wings on Kobe, hitting fabric and synthetic rubber plants and halving the capacity of the shipyard.

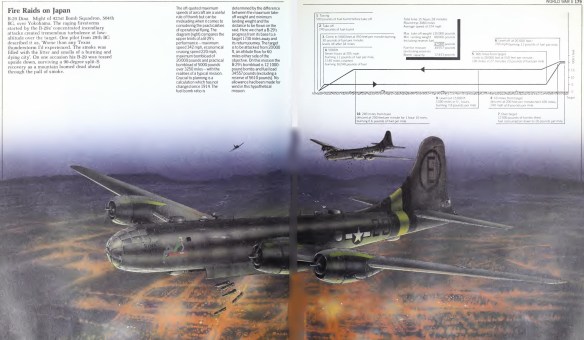

LeMay issued a directive embodying these new tactics on February 19. On February 25 and March 4 they were tested in two raids on Tokyo. In the first, 30 000 buildings were gutted by 172 B-29s, which dropped 450 tons of incendiaries. The pattern was established and by May 1945 75 per cent of the B-29s’ bombloads comprised incendiaries; among the most effective was the 500-pound M76 ‘pyrotechnic gel’ bomb which had a special mixture of jellied oil. heavy oil, petrol, magnesium powder and sodium nitrate. These bombs were all but impossible to extinguish. LeMay now introduced additional tactical refinements. To counter the jetstream, high-level daylight raids were replaced by low-level high intensity incendiary attacks, preferably by night. The B-29s were stripped of their GEC gun systems, leaving only the tail gun for defense, packed with incendiaries and pulled down to an operating height of 6000 ft. The first raid of this kind was flown against Tokyo on the night of March 9/10 by 325 B- 29s led by special pathfinder crews. Of these 279 arrived over the target and in two hours of bombing razed the central area of Tokyo. Sixteen square miles of the city were destroyed and 84 000 people killed for the loss of 14 B-29s.

On March 11/12 285 B-29s unloaded 1700 tons of incendiaries on Nagoya, leveling two square miles of the city for the loss of only one aircraft. There were now only 500 aircraft of low serviceability defending Japan, including two night fighter groups equipped with rudimentary radar. Because of the system of Army command over the home defense units, each fighter group was assigned to a specific territory and could not be used for operations in support of neighboring areas. Ground-to-air communications were too poor for concentrated control of fighters, even in the relatively small defense areas.

On March 13/14 eight square miles of Osaka were swept by a firestorm; on March 16/17 three square miles of Kobe were razed, and three nights later a similar blow was delivered to Nagoya. In two weeks over 120000 Japanese civilians were killed or injured, for the loss of 22 B-29s. By March 20 XXI BG had exhausted its stock of incendiaries. It was the final triumph of area bombing. By April 1945 LeMay had over 700 B-29s at his disposal, enabling him to divide his force between the tactical support of the Okinawa landings and the continuing incendiary offensive against the major Japanese cities – Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Kawasaki, Kobe and Yokohama. On April 13 327 B-29s destroyed another 11 square miles of Tokyo with over 2000 tons of incendiaries. The Japanese night defenses had rallied and five aircraft were lost on this raid and 13 more on April 15 in attacks on Tokyo, Kawasaki and Yokohama. These were negligible losses, and the arrival of 58th Wing from the CBI now enabled LeMay to contemplate the use of 500 B-29s in a single raid and the ending of the war with the bludgeon of air power.

On May 14 a new series of crippling fire raids began with an attack by 472 B-29s on the area surrounding the Mitsubishi engine plant at Nagoya. In this and another attack on May 16/17 a total of nine square miles were engulfed by firestorms, stampeding the terrified population into the surrounding countryside. On May 23 LeMay mounted the largest single B-29 raid of the war when 562 aircraft took off to raid Tokyo and 510 bombed the target. Two days later 464 B-29s returned to drop incendiaries in the areas which had not been hit. Although 43 aircraft were lost in these two raids, the Japanese capital had been reduced to a charred wasteland. By the end of May over 50 per cent of the city area of Tokyo, about 56 square miles, had been destroyed.

Troubled by the losses on these raids, LeMay changed his tactics, with the twin aim of catching the defenses off balance and drawing the Japanese fighters into an air battle which would drain their remaining strength. On May 29, in a high-altitude raid, 454 B-29s appeared over Yokohama heavily escorted by P-51 Mustangs from Iwo Jima. In the ensuing dogfights 26 Japanese fighters were shot down for the loss of four B-29s and three Mustangs. Japanese interference with the raiders now fell away as they husbanded their dwindling strength for a final spasm of Kamikaze attacks against the anticipated Allied invasion force. By June 1945 the B- 29s flew unmolested over the shattered cities of Japan. At the end of the month no less than 105.6 of the combined 257.2 square miles of Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Kawasaki, Kobe and Yokohama had been flattened.

Operating with almost complete freedom, LeMay adopted a variety of tactics. On April 7 he initiated a program of high-level precision strikes with an attack by 153 B-29s on the aircraft engine plant at Nagoya. Six hundred tons of HE wrecked 90 per cent of the remaining facilities. Five days later 93 B-29s completed the destruction of the Nakajima factory at Musashi. The task of neutralizing Japan’s remaining oil-producing and storage facilities was given to 315th BW, stationed on Northwest Field, Guam, and equipped with the stripped-down B-29B capable of carrying a standard load of 18 000 pounds. Navigation and bombing accuracy were improved by the AN/ADQ-7 ‘Eagle’ radar, housed in a wing shaped radome underneath the fuselage. The aircrew in 315th BW had received a rigorous training in low-level nighttime bombing. The task was completed by August 10. The last nails were hammered into the Japanese coffin by 313th BW, which between March 27 and August 10 sowed nearly 13 000 acoustic and magnetic mines in the western approaches to the Shimonoseki strait and the Inland Sea, and around the harbors of Hiroshima, Kure, Tokyo, Nagoya, Tokuyama, Aki and Noda. By the end of April Japanese coastal shipping movements had been brought to a standstill. In May, 85 ships totalling 213 000 tons were sunk in attempts to break out.

With Japan’s major cities lying in ruins, LeMay focused his attention on smaller conurbations of between 100 000 and 200 000 people. The program began on June 17 with low-level incendiary raids on Kagashima, Omuta, Hamamatsu and Yokkaichi. Fifty-seven cities were hit in these secondary attacks. One of them, Toyama, was 99.5 per cent destroyed. In July a refinement was introduced – reminiscent of the plans to proscribe’ German cities which had been discussed by the British Air Staff in 1918 and 1941. Leaflets warning of forthcoming attacks were dropped over selected Japanese cities and every third night thereafter the B-29s returned with their cargoes of incendiaries.

After four months of relentless bombardment LeMay was running out of targets to attack. Japan had been brought to the brink of surrender.