Since the early 1930s, while Ernst Heinkel worked on his jet engine, Frank Whittle had been engaged in a double struggle—with the problems of perfecting a gas turbine driving a series of enclosed impellers, and with trying to interest the RAF in his project. In 1939, Whittle joined creative forces with George Carter, chief designer for the Gloster Aircraft Company, and at about that same time the Air Ministry finally took an interest in the jet concept, issuing a contract to Gloster for an experimental airframe that could be adapted for operational use with minimum modification.

The result of Whittle’s and Carter’s efforts, the single-engine Gloster E28/39 finally flew at RAF Cranwell on May 15, 1941. Although the maiden flight lasted little more than a quarter of an hour, test pilot Phillip E. G. Sawyer emerged from the cockpit praising the plane, declaring that the jet was indeed the way of the future. The RAF was already convinced of that, for by then it had issued Specification F9/40, calling for five hundred twin-engine fighters using Whittle’s engine.

Eight developmental aircraft were built, the fifth of which, DG206, made the F9/40’s first flight from RAF Cranwell on March 5, 1942, with Michael Daunt at the controls. Whittle’s WSB engines were still being built at the Rover plant in Coventry, so de Havilland H1 Halford engines were substituted for the first flight. Although the plane exhibited a few problems, including a tendency to yaw violently as its speed approached 230 miles per hour, the Air Ministry found it promising enough to continue development, starting with redesigned larger tail surfaces. Trials were switched to Newmarket Heath, then to Barford Saint John, and finally to Moreton Valence, once a hardened runway was completed there. Policemen closed the roads whenever the Meteor, as the new jet was then being called, flew. Test flights were usually conducted when there was low cloud cover, to reduce the odds of unauthorized eyes seeing the top-secret fighter.

Meteor DG205/G, fitted at last with the Whittle-developed W2B engine, made its first flight on June 17, 1943. Development continued at a rather slow pace until the first production Meteor F Mark 1, EE210/G, flew from Moreton Valence on January 12, 1944. The production aircraft used Rolls-Royce-built W1B Welland I engines, but apart from a modified canopy and the installation of four 20mm Hispano Mark V cannon in the nose, it differed little from the prototype. Rated at 1,600 horsepower, the Welland I was a reliable and tractable power plant, but because of the Meteor’s size, rather than its modest weight, the plane was only able to reach a speed of about 390 miles per hour at sea level and a maximum of 415 miles per hour at higher altitudes, with a service ceiling of 40,000 feet. Given that less than exhilarating performance, some RAF people suggested that it was fit only to serve as a trainer. By then, however, the Air Ministry was aware of the Me 262 and of its imminent introduction to service, and consequently judged it psychologically important that the RAF have a jet of its own in frontline squadrons.

Another psychological factor arose that would serve as the ultimate call to arms for the Meteor. On June 12, 1944, the first V-1 (Vergeltungswaffe, or Vengeance Weapon) was launched against London. A pilotless flying bomb packing a ton of high explosive in the nose, powered by a simple, externally mounted pulse-jet engine, guided by gyros, and made to fall on its target when its predetermined allotment of fuel ran out, the V-1—or “Buzz Bomb,” as it came to be called by its intended victims—was meant to terrorize the British home front for the first time since the Battle of Britain, in reprisal for the Allied landings in Normandy six days earlier. To the RAF, it seemed almost a matter of destiny that its first jet should be among the aircraft mobilized to defend England against these swift, small, jet-propelled flying robots.

The unsuspecting first recipient of the Meteor was No. 616 Squadron, Auxiliary Air Force, which in June 1944 was flying Spitfire Mark VIIs from Culmhead, Somerset, on escort missions for bombers striking at German tactical targets in France. Rumors had been rife since the spring that the squadron was to be reequipped, but most pilots believed that the replacements would be Rolls-Royce Griffon-engine Spitfire Mark XIVs, two of which arrived at Culmhead in June. Shortly afterward, Squadron Leader Andrew McDowall and five other pilots were summoned to Farnborough to acquaint themselves with the new aircraft, but when they returned, they announced that 616 Squadron’s replacements would be jets—and unanimously added that once they had gotten accustomed to their tricycle landing gear, they were delightful machines to fly.

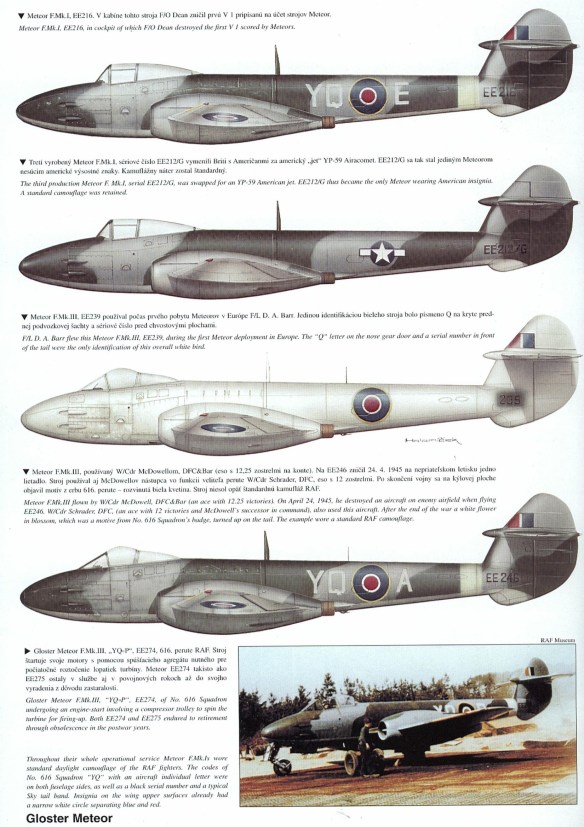

The first two Meteor Is, EE213 and EE214, began flying with 616 Squadron on July 12, 1944. Five more Meteors arrived on the fourteenth, and by the twenty-fifth squadron strength had reached a dozen, completely replacing its Spitfire VIIs. On July 21 two of the Meteors, escorted by the squadron’s Spitfires, flew to Manston airfield in Kent, followed two days later by five more jets. From there, newly promoted Wing Commander McDowall, Wing Cmdr. Hugh J. Wilson, Squadron Leader Leslie W. Watts, Flying Officers William H. McKenzie and T. J. Dean, and Warrant Officer Wilkes commenced operations against the V-1s.

At 1430 hours on July 27, 1944, Bill McKenzie flew the first Allied combat mission in a jet, patrolling around Ashford without incident. More “diver patrols,” as the RAF code-named its efforts to stop the flying bombs, were flown that afternoon by Dean and Watts, the latter catching up with an incoming V-1 over Ashford. With the “doodlebug” in his gunsight, Watts pressed the trigger button on the control column, but nothing happened. His guns had jammed, and the V-1 escaped and went on to hit its target. After that setback, it was decided that patrols against the vengeance weapons should be carried out by pairs of aircraft, since the odds of both Meteors’ guns jamming were unlikely. In order to increase their time in the air, the squadron moved its Meteors to a dispersal aerodrome near Ashford, reducing the distance they had to fly to reach the V-1s’ expected routes.

Finally, on the evening of August 4, “Dixie” Dean was only minutes from takeoff at Ashford when he spotted a V-1 ahead of and below him, heading toward Tunbridge Wells. Going into a shallow dive, Dean increased his speed to 385 miles per hour, then got in a brief burst of his guns before they jammed. Dean then brought the Meteor alongside the V-1 as close as he felt safe, slid his wing under the V-1’s and slowly pushed his control column to the left. As Dean’s plane banked, the force of air lifted the robot’s wing, unbalancing its autopilot until it abruptly flicked over on its back and dived into the ground, exploding harmlessly in the open countryside. Contrary to popular belief, the Meteor’s wingtip did not actually touch the V-1 during these “tip-and-run” tactics, since there was too much chance of damaging the fighter or even the loss of valuable pilots and aircraft. Air pressure sufficed to do the job.

Within minutes of Dean’s success, Flying Officer J. K. Rodger closed on another “diver” over Tunbridge and opened fire with his four 20mm cannon. This time, the weapons did not jam, and the V-1 went down in open countryside near Tenterden.

After that, 616 Squadron relayed two-plane patrols throughout the day, each flight lasting about thirty minutes. By August 10, Dean had added two more divers to his score. On August 16 and 17, the Meteors accounted for five more of the robot bombs. A total of thirteen V-1s were destroyed in one way or another by 616’s “Meatboxes”—modest in number, but a great boost to public morale.

Aside from its guns, the Meteor gave no trouble, and its two engines needed less servicing than the single engine of a Spitfire. Indeed, the only thing bad that happened to No. 616 Squadron was when one of its Meteors was almost shot down in error by a Spitfire and had to land under control of the elevator trimmers.

For the remainder of 1944, 616 Squadron’s Meteors operated from Debden, where they were used to acquaint RAF and USAAF units with the characteristics of jets, and to help them develop tactics to counter the Me 262As that were starting to take their toll of bomber formations. After being subjected to hit-and-run strikes by the Meteors, the American P-51 and P-47 pilots concluded that the only way to protect the bombers was to increase their numbers 5,000 feet above them, allowing the fighters time to build up speed to intercept the German jets. Such tactics required split-second timing at high speeds, but they paid off, as a number of Americans added Me 262s to their scores while on escort duty.

On December 18, No. 616 Squadron received its first two Meteor F Mark 3s, EE231 and EE232, which were powered by Rolls-Royce Derwent engines in revised nacelles. In addition to improved performance, the F3 had a larger fuel capacity, which gave it an hour’s longer endurance; an enlarged, more streamlined windscreen; and a rear-sliding bulged bubble in place of the F1’s side-hinged canopy. Three more Meteor 3s were on strength by January 1945, when the unit moved to Colerne, Wiltshire. There, the squadron exchanged the last of its Mark 1s for the newer type, and on January 20 one of the flights was dispatched across the Channel to Melsbroek, near Brussels, Belgium, to join No. 84 Group of the Second Tactical Air Force. For some weeks, the Meteors flew patrols over local Allied airfields, primarily to acquaint them with the new jet’s silhouette. While there, the squadron had its closest brush with its technological counterparts on March 19, when the air base was raided by four Arado Ar-234B-2 jet bombers of II Gruppe, Kampfgeschwader 76. The rest of the squadron arrived on March 31, and in early April it resumed offensive operations from Gilze-Rijen in the Netherlands as part of No. 122 Wing.

As was the case with the German jet fighter units, 616 Squadron’s personnel now included some skilled veterans, including Wing Cmdr. Warren Edward Schrader from Wellington, New Zealand, who had previously flown Hawker Tempests in No. 486 Squadron and had eleven victories, plus two shared, to his credit. An identical victory tally had been scored by Wing Commander McDowell from Kirkenner, Scotland, but he had done so in Spitfires with No. 602 Squadron. Much to the disappointment of the pilots, however, no contact was made with the Luftwaffe in the course of their short patrols, and in consequence they were employed in the armed reconnaissance and ground-attack roles.

On April 13, No. 616 Squadron moved to Nijmegen, and on the fourteenth, Flt. Lt. Mike Cooper became the first “Meatbox” pilot to fire his guns in anger over the Continent when he spotted a large German truck near Ijmuiden and in a single firing pass sent it careening off the road, to burst into flames seconds later. On the twenty-fourth, McDowell, flying Meteor F1 YQ-A, led four others on a strike against an enemy airfield at Nordholtz, Germany. Diving out of the sun from 8,000 feet, he destroyed a Ju 88 on the ground and shot up a vehicle. Flying Officer Ian T. Wilson set two petrol bowsers on fire and used up the rest of his shells on other airfield installations. Flying Officer H. Moon roamed the perimeter of the field, strafing a dozen railway trucks and destroying a flak post. Flying Officer T. Gordon Clegg attacked a large vehicle full of German troops who, thinking the twin-engine jet to be one of their own, waved and cheered until Clegg opened fire.

Up to that time, 616 Squadron had taken no casualties, but that unblemished record came to a tragic end on April 29, when Squadron Leader Watts, who had been with the unit since August 1943, collided with Flt. Sgt. Brian Cartmell in a cloud bank. The two planes exploded, and both pilots were killed.

On May 2, Wing Cmdr. “Smokey” Schrader replaced McDowell as commander of No. 616 Squadron. On the same day, one of the “Meatbox” pilots encountered a Fieseler Fi.156 Storch, but the nimble liaison plane was able to outmaneuver the fighter and landed—after which the Meteor strafed it to destruction. On May 3 Schrader, flying Meteor YQ-F, led the squadron in an attack on Schönberg air base near Kiel, during which six aircraft were destroyed on the ground—Schrader personally accounting for an Me 109, an He 111, and a Ju 87. On another occasion, four Meteors encountered some Fw 190s, but their hopes of adding some air-to-air victories to the squadron tally were again frustrated when some Spitfires and Hawker Tempests mistook the British jets for Me 262s and prepared to attack, compelling the Meteors to abandon their attempt against the Germans. On the following day, 616 Squadron’s pilots destroyed one locomotive, damaged another, knocked out ten vehicles and two half-tracks, and strafed a number of installations. At 1700 hours, the unit was ordered to suspend offensive operations. Four days later, Germany surrendered.

It is probably fortunate for the Meteor pilots that they never had to do battle with the Me 262s—all other things being even, neither their aircraft nor their own level of expertise would have matched the performance of the German fighter, nor of the crack Experten who were flying it in the final weeks of the war. Nevertheless, the “Meatbox” proved to have considerable development potential, and on November 7, 1945, a Meteor F3 piloted by Wing Cmdr. “Willie” Wilson reached a record speed of 606 miles per hour. Progressively improved marks were to follow, serving in the fighter, reconnaissance, and night-fighter roles until September 1961, by which time a total of 3,875 Meteors had been built.