But with the best will in the world, the idea of the early Vikings as speedy Baltic commercial travellers, singing their sagas as they rowed to a new market opening, doesn’t ring quite true. Towards the end of the eighth century the reeve Beaduheard in Dorchester went to meet what he innocently supposed was a fleet of peacefully inclined Norse trading ships. He directed them to the loyal royal estate and was thanked for his helpfulness by an axe in the face. The Vikings were certainly partial to one kind of inventory – people (including women), whom they sold as slaves. A thousand such slaves were taken from Armagh in one raid alone in 869. A burial dated to 879 contained a Viking warrior with his sword, two ritually murdered slave girls and the bones of hundreds of men, women and children – his very own body count to take with him to Valhalla.

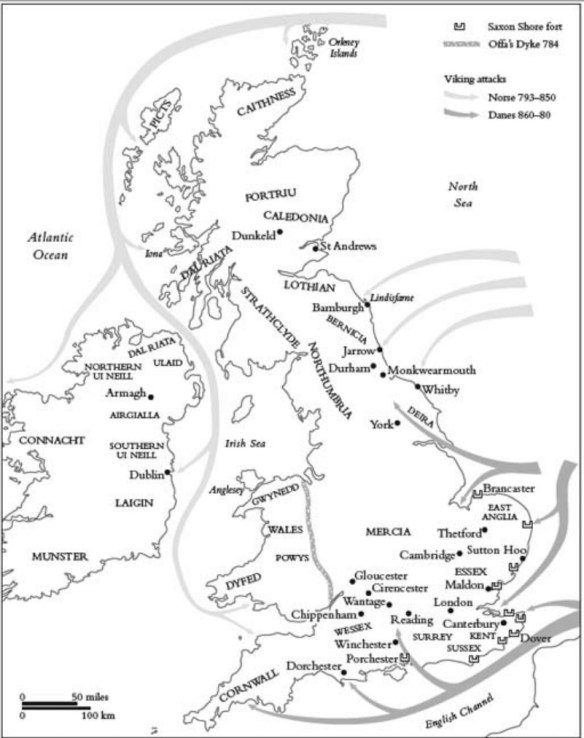

So it seems likely that the inhabitants of ninth-century Britain would have had some difficulty in finding the Norsemen ethnographically fascinating, being too busy defending themselves against dismemberment or being dragged off into captivity. Just because so many of the tales of their early impact on Anglo-Saxon life are alarmingly violent, and because they come from Anglo-Saxon, Church sources, does not necessarily mean they were untrue. Gaelic sources tell much the same story. At Strangford Lough, the ancient abbey closely associated with St Patrick’s earliest preaching in Ireland was completely destroyed. In 795 another of the iconic sites of the Christianization of Britain – Iona – was sacked, and in 806 sixty-eight of its monks were killed. Houses, then, which were vulnerable to attack from rivers, loughs or coastal estuaries had very good cause to take the Viking threat seriously. A small cathedral at Bradwell-on-Sea in Essex, founded in the seventh century by a far-ranging mission from Northumbria, had been built on the foundations of a Roman fortification, and the monks must have been grateful for the solid masonry defences while they waited nervously for Viking raids, which they knew, sooner or later, would strike fast and fierce.

On the positive side, however, there was one thing that the Vikings did manage to do – albeit inadvertently – and that was to create the need for a consolidated kingdom of England and of Alba, too, which eventually became known as Scotland. This was not what they had in mind when their longships sailed swiftly and lethally upstream. What they had in mind, principally, was loot. The Vikings came from a Scandinavian society that was itself a near-anarchy of warrior lords, making gestures of allegiance to their kings in Denmark and Norway, but for the most part being permitted to operate as freebooters, taking as much land, plunder and captives as they wished. Better the marauder away than the marauder at home. The idea, before the Vikings began to settle themselves in occupied areas of eastern and northern England, was to inflict enough violence on a kingdom for its ruler to buy them off, preferably in hard silver. The principle was crude, but the delivery of the violence was efficient, and it hit the Saxon kingdoms at a time when they were themselves divided both between and within each other. The marriage alliances between the Saxon states had proved, under pressure, to be no guarantee of military solidarity, especially when Viking damage might be thought of as a calamity for somebody other than yourself. In fact, some of the Saxon rulers repeated the mistakes of the Romano-British four centuries before, by actually welcoming the invaders as a useful auxiliary.

Before he died in 735 Bede had worried a great deal about whether the Christian tree of belief had been planted deeply enough to survive the threats he saw coming from both pagan resurgence in the shape of the Norsemen and the new militant religion of Islam, which had thrust deep into the heart of Christian Spain and France. But even Bede’s pessimism couldn’t begin to imagine the scale of devastation that the Vikings would inflict on Northumbria, not only on Lindisfarne, but on his own monastery at Jarrow, and at Monkwearmouth and Iona, the capture of York and, most painful of all, the burning of the great libraries of the monasteries. When he heard of the annihilation at Lindisfarne, Alcuin of York, the court scholar to Charlemagne, the great Frankish Holy Roman Emperor, wrote: ‘Behold the church of St Cuthbert, spattered with the blood of the priests of God.’

By smashing the power of most of the Saxon kingdoms, the Vikings accomplished what, left to themselves, the warring kings, earls and thegns in England and the mutually hostile realms of Dal Riata and Pictland in the north could never have managed: some semblance of alliance against a common foe. After two decades of attacks in the north, the Pictish king Constantine I, consciously taking his name from the first Roman-Christian emperor, defeated the Dal Riata and united the kingdoms in 811. Likewise, it took the threat of common, irreversible catastrophe for the rulers of what remained of non-Viking England to bury their differences and submit to the overlordship of a single king, a king of all England. To attract this kind of unprecedented allegiance, such a figure would have to be exceptional, and Alfred, of course, fitted the bill. The Tudors thought him inspiring enough to award him, alone of all their predecessors, the honorific appellation of ‘Great’ in direct analogy with Charlemagne, Charles the Great. And for all the mythology about Alfred, it can’t be said that they were wrong. The Anglo-Saxons called him Engele hirde, engele dirling (England’s shepherd, England’s darling).

When he was born – in Wantage in 849 – the youngest son of King Aethelwulf and the grandson of King Egbert of Wessex, that realm, through the usual combination of war and marriage, had replaced the midland kingdom of Mercia as the dominant Saxon kingdom. The Vikings were still largely thought of as periodic inconveniences, mounting raids, stealing as much as they could from shrines or busy Saxon market towns like Hamwic (the ancestor of modern Southampton), extorting money and then mercifully departing to enjoy the proceeds. But of late their fleets had been getting bigger – thirty, thirty-five ships at a time – and their stays were becoming ominously more protracted. In the 850s they began to stay through the entire winter in Thanet and Sheppey in Kent. In 850 a fleet, which The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle put as high as 350 ships, captured Canterbury and London and sent the Mercian king, Berhrtwulf, packing. Nor could silver be relied on any longer to keep them at arm’s length. In 864 the ealdormen (noblemen) of Kent had duly coughed up but the Vikings had decided to put the area to the sword anyway, just for the hell of it. The following year, 865–6, was the year in which the great Christian kingdom of Northumbria was destroyed at the hands of the biggest Viking fleet Britain had yet seen, with York falling in 867. By 876 the Northumbrian lands were being shared out among their principal chiefs. In 869 it was the turn of the king of East Anglia, Edmund, who, sick of making the usual payments, turned to resistance and suffered decapitation and impalement. It was now obvious to Aethelred, the king of Wessex, and to his only surviving brother, Alfred, that they, too, could not avoid confronting the Vikings for very much longer.

Much of what we know about Alfred comes from the biography written by the Welsh monk Asser, invited to the king’s court and doubtless eager to sing his praises. Allowing for idealization, though, the portrait somehow has the ring of truth, even the child already hungry for learning. Asser’s most famous tale of the boy-wonder describes Alfred’s mother offering to give a decorated book of Anglo-Saxon poetry to whichever child could learn the contents. Needless to say, Alfred not only committed the poems to memory but recited them out loud to his mother, half bookworm, half show-off.

But these were not bookish times. In 868, with the Vikings wintering in Mercian Nottingham, Alfred was married, in an obvious tactical alliance, to Eahlswith, whose mother was a member of the Mercian royal family. By 870 the Danes were in Reading, a direct challenge to the kingdom of Wessex. In 871 the two brothers, Aethelred and Alfred, fought a series of battles culminating in the victory of Ashdown. But before he could enjoy the success, Aethelred died, leaving Alfred the kingdom. The news that a second, enormous Viking army had come to Reading was not reassuring. With the collapse ofWessex apparently imminent, the entirety of Anglo-Saxon England seemed about to go the way of Roman Britain.

But then a series of small miracles intervened. The one failing in the otherwise impressive Viking killing machine was its tendency to congratulate itself on victory by splitting itself into pieces; not so much divide and conquer as conquer and divide. Presumably confident it could never be withstood, the great pagan Viking armies of 865 and 871 went their separate ways. In 874 some of the senior class of 865 returned to Norway, the rest settling down in Northumbria for the long term. The junior class of 871, led by a jarl (chieftain) called Guthrum, moved to Cambridge, from where it calculated it would make Wessex, to the south and west, its very own milch-cow. When Guthrum moved on Gloucester, this seemed about to happen.

For the moment, Alfred had no choice but to temporize, making treaties and exchanging hostages with Guthrum in an attempt to get the Vikings out of Wessex and into Mercia. For a while, the tactic seemed to work, even though Alfred must have been pessimistic about holding a pagan like Guthrum to any kind of sworn oath. Sure enough, on Twelfth Night, January 878, in the dead of winter and knowing that Christians like Alfred were distracted with celebrating the Epiphany, the Vikings launched a surprise attack on the royal Wessex town of Chippenham. The plan must have included the capture of the king and it very nearly succeeded. Virtually defenceless, Alfred was forced to take flight.

What happened next is the heart of Alfred’s legend. A fugitive in the bulrush-choked swamps of Athelney, he began to turn the tide against the enemy, using the inaccessible bogs as a defensive stronghold. Asser describes the prototype of the guerrilla fighter, leading ‘a life of great distress amidst the woody and marshy places of Somerset [with] nothing to live on except what could be foraged from raids’, reduced to begging hospitality from peasants, including the swineherd’s wife, who gave him such a bad time for burning her cakes. The stories, both then and later, have the tone of scripture (or at least apocrypha): a proud king reduced to abject destitution and stoical humility (especially when dressed down by an indignant woman); but then, when flattened by misfortune, blessed with the inspiration to take hold of his and his country’s destiny. In one of the many later stories surrounding the wandering king on the run, no less a person than St Cuthbert (who else?) appears and asks to share his meal. The king obliges. The stranger vanishes only to appear in full saintly get-up, promising eventual success and urging Alfred, like Gideon, to trust in God and blow blasts on his battle horn to summon his friends.

By the spring of 878 Alfred had managed to piece together an improvised alliance of resistance, and at King Egbert’s stone, on the borders of Wiltshire and Somerset, he took command of an army that, two days later, fought and defeated Guthrum’s Vikings at Edington. It was a victory so complete that Alfred was able to pursue them all the way back to Chippenham and besiege them for two weeks before the Viking chief capitulated. And this was no ordinary surrender. Guthrum was sufficiently impressed by the power of Alfred’s battle-god that he decided forthwith to enrol in the ranks of the Christian soldiers along with thirty of his warriors. He accepted baptism at the church of Aller in Somerset, where Alfred stood as his godfather, raising him from the font. The hitherto fiercely pagan Viking lords were now clad not in armour but, head to foot, in the soft white cloth of converts; their baptismal garments removed on Alfred’s royal estate at Wedmore as the solemn ceremonies were completed. So the victory over Guthrum was both martial and spiritual. Alfred had made a believer of him and received him into the community of the English Church, so it was now possible to make a sacred, binding treaty (so the king must have hoped anyway) in which Guthrum agreed to be content with his mastery of East Anglia and desist from attacking Wessex, Mercia or the territories of Essex and Kent, also ruled from Wessex proper. And this seems to be more or less what happened. Guthrum withdrew to Hadleigh in Sussex where perhaps he spent a bucolic retirement pottering about in un-Viking-like harmlessness.

Alfred was much too intelligent to be carried away by a premature sense of triumph. A single jarl and his army had been defeated, not the whole of the Viking power in England. By the end of the ninth century it was more than ever clear that the Norsemen were in the island for the long haul, no longer as raiders and pirates but as colonists. Alfred’s best hope was containment, for a modus vivendi with a Christianized and, therefore, relatively peaceable Viking realm. And although it was not quite the epic of historiographical legend, Edington did make the Viking kings pause in their sweep across the island and bought Alfred fourteen years of priceless respite, a period in which he constructed a formidable chain of thirty defensive forts called burhs, permanently manned garrisons, strategically based on the accumulated military wisdom of generations of ancestors: Iron Age hillforts, Roman roads, and Saxon dykes and ditches. His part-time army of the fyrd, raised from the thegns who owed service to his senior lords, was now equipped with horses, and put on rotational shifts of duty, so that whenever and wherever the Vikings appeared, they would always have a serious opposing force to contend with. When the Vikings did return in the early 890s, as Alfred had anticipated, they no longer had the operational freedom they had enjoyed in their marauding heyday in the middle of the ninth century. Alfred’s campaign forced the Vikings to settle for much less than half of the country, and a border running through East Anglia, eastern Mercia and Northumbria hardened into a frontier between Danish and Saxon England.

It was, at best, a stand-off. But when in 886 Alfred entered London (which he had refounded on its old Roman site, rather than the Mercian-Saxon Lundenwic sited near present-day Aldwych and the Strand), something of a deep significance happened. He was, as Asser wrote, acclaimed as the sovereign lord of ‘all the English people not under subjection to the Danes’. And it was at this time that he began to be called ‘King of the Anglo-Saxons’. Some coins of the period actually go further and style him rex Anglorum (king of the English), the title with which his grandson Aethelstan would be crowned in 927. So there can be no question that during Alfred’s lifetime the idea of a united English kingdom had become conceivable and even desirable. The exquisite ‘Alfred Jewel’, which was found not far from Athelney, bears an extraordinary enamelled face, perhaps like the similar Fuller brooch, its staring eyes symbolizing Sight or Wisdom, a wholly apt quality to celebrate an omniscient prince. The ‘Alfred Jewel’ is inscribed on its side with the legend Aelfred mec heht gewyrcan (Alfred caused me to be made). The same perhaps could be said of his reinvention of an English monarchy.

In truth, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England was still as much a work in progress as was the mac Ailpin kingdom in Scotland under Kenneth I. But by the time he died in 899, Alfred certainly had transformed the office of kingship itself. What had been a warrior chieftaincy, the giver of rings (and Alfred was still celebrated as the greatest ring-giver of all), was now also an institution of classical and biblical pretensions. The king who was the translator of the psalms could never have been far from thinking of himself as a new David or Solomon. Like David, he would be the right arm of the Church of God – and a sword found at Abingdon suggests just how seriously he took this role. Like Solomon, Alfred assumed that the authority of the king should rest on something other than the arbitration of force, namely justice. So he was the first of the kings to set about combining the different law codes and the penalties for their infraction into a single, coherent whole and having them written and translated so that his subjects (or at least the half of them that were free, for it must always be kept in mind that Saxon England was a slave society) could have access to royal justice as a matter of course. To be sure, the justice that Alfred offered was kept well within the bounds of realism. Aware of the hopelessness of attempting to outlaw the blood vendetta, Alfred merely insisted that the king should regulate it, giving a grace period, for example, to the attacked party to come to terms before he was set upon. Pained by the memory of the Viking burning of monastic libraries, Alfred also saw the king as an educator. In his translation of Boethius’s De consolatione philosophiae (The Consolation of Philosophy) Wisdom gets the best lines, but Alfred’s commitment to instruction was also of a practical kind. Establishing schools, not just for his family and the court but for all his nobility too, was a statement of intent that henceforth those who presumed to govern in the name of the king should do so as literate, educated men, rather than as the bearers of swords and the takers of purses.

It was an extraordinary thing that Alfred’s most fervent conviction was that the condition of exercising power was the possession of knowledge. Of how many other rulers of British realms could that truly be said?

The Saxon kings had come a long way from the ferocious pagan axemen of the adventum to the makers of libraries! Of course, this vision of a peaceful, studious Anglo-Saxon Wessex was more of a noble ideal than an imminent reality. More than half the country was securely in the grip of the Vikings, and although in the tenth century the sovereignty of the Wessex-based kings of England would extend to the border of the Tweed, it was on condition that the Viking zone of control, the ‘Danelaw’ as it came to be known, would enjoy its own considerable autonomy. By the end of the tenth century a second coming of aggressive Viking raids would once again attempt to reach deep into the territory of Anglo-Saxon England, and early in the eleventh century a Danish king, Cnut, would reign over the whole country south of Hadrian’s Wall. But he would reign largely as the beneficiary of the Anglo-Saxon government established by Alfred and his successors.

Although the dynasty of the house of Wessex was battered and bloodied through all these years of tribulation, and was often on the point of being wiped out altogether, the ideal of English kingship that had crystallized under Alfred persisted. And it is one of the most profound ironies of early British history that it was, at heart, a Roman ideal of rule, which was implanted in the breasts of the Saxon cultures usually thought of as having buried the classical tradition. This was equally true north of the Tweed, where the kings of Alba (as they called the old Pictland after 900) named their sons alternately with Gaelic and Latin names – so that a Prince Oengus would be brother to a Prince Constantine. Alfred had, in many ways, been the most Roman of Saxons. When he was just a child, in 853, his father, Aethelwulf, had sent him on a special mission to Rome where Pope Leo IV had dressed the little fellow in the imperial purple of a Roman consul and set around his waist the sword-belt of a Romano-Christian warrior. In 854–5 he had spent another whole year in Rome with his father, collecting the kind of memories, even of the Palatine hill in ruins, that an Anglo-Saxon would hardly forget. Learning Latin in his adult life and translating Pope Gregory’s Pastoral Care finally set the seal on this ardent Christian Romanism. And during the pontificate of Pope Maximus II, Alfred inaugurated the tradition by which every year, in return for freeing the English quarter of the city from taxes, the alms of the king and people of England would be sent to Rome, a tradition that ended only with the reformation of Henry VIII.

Of course, the Rome to which Alfred was evidently devoted was not the pagan empire from which Claudius and Hadrian had sent their legions into the island, inventing Britannia. It was, rather, the new Roman Christian empire. If Alfred had had a model in mind for his own exalted concept of kingship it surely would have been Charlemagne, and Alfred’s policy of bringing learned clerics to court seems to have been in direct emulation of the Frankish emperor. All the same, when his great-grandson, Edgar, was crowned, twice over, in 973 with solemnities designed by Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury (who must have known something about antiquity), the rituals that remain at the heart of English coronation to this day – the anointing, the investment with orb and sceptre, the cries of acclamation, ‘Long live the king, may the king live forever’ – owed as much to the Roman as to the Frankish tradition. And where did those two coronations take place? In the two places in England that most profoundly embodied the fusion of Rome and ancient Britain: Bath and Chester.

For whatever else he understood about this, Edgar was bright enough to know that, if he were to survive, the one thing a king of England could not afford was insularity.