On 10 January 1941, while Illustrious was covering a convoy entering Valletta’s Grand Harbour, the Sicilian-based Fliegerkorps X carried out a devastating attack, coordinated with an ineffectual Italian torpedo strike. The latter did, however, have the effect of drawing the patrolling Fulmars down to low level as the Ju 87s came to their ‘pushover’ point 11,000ft above, and there was thus little that the fighters could do to prevent the first wave of dive-bombers from bombing the carrier, defended only by the fleet’s AA fire. In this first attack she was hit by six 250 and 500kg bombs, three of which inflicted only superficial damage. The others all hit the flight deck aft, but only one actually penetrated the armour. The other two, and a seventh hit in an attack four hours later, hit on or about the after lift. The after hangar was set on fire and four Fulmars contributed to the blaze, which spread to compartments around the after lift well. Near misses caused a complete steering failure, and Illustrious was out of control for nearly three hours. However, her machinery was intact and her watertight integrity was unaffected, and she was able to keep moving at up to 18kts throughout, as well as being able to maintain power for fire-fighting pumps and communications. Once under control again Illustrious headed for Malta, protected by Valiant, Warspite and those Fulmars which had been able to refuel and rearm at Malta, 60 miles to the east of the scene of the attack. Grand Harbour was reached at dusk and the ship entered with her fires still out of control. They were not finally extinguished until the following morning. There is no doubt that the armoured deck saved her from destruction; no other carrier took anything like this level of punishment and survived.

Illustrious was bombed again while emergency repairs were carried out at Malta, receiving two more direct hits on 16 January and suffering serious damage to the bottom plating from the mining effect of near-misses on the 19 th. The Fulmars joined the few RAF Hurricanes on the island in the defence of their ship, and she eventually broke out on the evening of 23 January, bound for the Suez Canal and virtual rebuilding above the main deck in Norfolk Navy Yard in the USA. She did not return to the UK until the end of 1941.

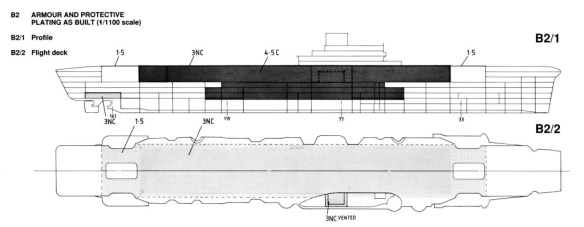

Remarkably, there was a great debate among naval theorists concerning the need for armor decking, yet their thinking was not completely irrational. The carriers that were built with armored decks fall into two distinct types – those with armor at the flight deck level protecting the below deck hangars, and those that only had armor between the hangar deck and the lower levels of the ship. Armor at the flight deck level would protect the hangar deck and the aircraft stored there from most bombs, but it severely limited the aircraft capacity of the vessel. Armor was also often thinner than was really necessary for protection. This was done especially with aircraft carriers to make them significantly faster in steaming through the seas so that their speed made them much more capable of launching and recovering warplanes. This was always done by steaming the carrier rapidly into any wind that was present to help provide aerodynamic lift. The deck armor also tended to reduce the length of the flight deck. Metal deck armor, exposed to wide changes in temperature, needed complicated expansion joints to be functional. US and most Japanese carriers had their armor placed at the hangar deck level, essentially treating the hangar spaces and flight deck as mere superstructure. These areas proved very vulnerable to the blast from penetrating general purpose bombs and other explosions, which in turn caused massive casualties in comparison to British armored carrier designs.

The British had begun the practice of armoring their flight decks prior to WWII, and in this they were consistent with their belief in the efficacy of level-bombing. The Royal Navy was faced with the particular problem of designing a carrier that could survive under the heavy bombloads of nearby land-based planes to be expected in the confines of the Baltic, the Mediterranean, and the Channel. These demands resulted in the development of aircraft carriers whose flight decks were armored against 500 lb Armor Piercing bombs and 1000 lb General Purpose bombs.

Sunk February 22, 1942, it seems almost fitting that the first US Navy carrier built was also the first to be sunk in World War II. The unarmored USS Langley, a conversion, was just one of the many victims of the Battle of the Java Sea. Three waves of Japanese aircraft attacked making 5 bomb hits. Langley took a 10 degree list, was abandoned, and sunk by US destroyers with guns and torpedoes.

HMS Hermes, destroyed in the Indian Ocean by IJN dive-bombers and torpedo aircraft two months later, was the world’s first ship to be designed and built specifically as an aircraft carrier. In service since 1924, Hermes spent most of the war patrolling the Indian Ocean with a tiny compliment of bi-wing planes. She refitted in South Africa in February 1942 and then joined the Eastern Fleet at Ceylon. The ship was woefully short of AA batteries. The ship’s waterline belt armor was 3 inches (76 mm) thick, but her flight deck, which was also the ship’s strength deck, was just 1 inch (25 mm) thick—armor similar to that afforded a light cruiser. By way of comparison, HMS Ark Royal deployed in 1938 had 4.5 in (11.4 cm) of belt armor and 3.5 in (8.9 cm) of deck armor over its boiler rooms and magazines. Ark Royal was lost to U-boat torpedo attack in 1941.

The Eastern Fleet had recently been devastated by the IJN whose overwhelming airpower sank the battle cruiser HMS Repulse and battleship HMS Prince of Wales. Together with their escort destroyers, HMS Electra, Express, Tenedos, and HMAS Vampire, these two had formed the so-called Force Z Naval fleet sent out too late to rescue the British base at Singapore. It was hoped that Hermes and other ships assigned to join the fleet (the carriers HMS Indomitable and Formidable) would bolster the airpower necessary to prevent a repeat of such a disaster. The carrier, without aircraft embarked, and its escorting destroyer were quickly sunk by the Japanese bombers and torpedo planes in April 1942. Most of the survivors were rescued by a nearby hospital ship although 307 men from Hermes were lost in the sinking. Allied uncertainty concerning the best configuration for an aircraft carrier had increased to the point, thereafter, that the British Admiralty forbade builders from working above the hangar deck without express permission. The design flaws were rectified in the Illustrious and Implacable class carriers, under construction at the time.

The IJN carrier force during World War II had unarmored flight decks just like the Yorktown and Essex classes of the US Navy. Only at the very end of the war did the IJN attempt to armor its carrier decks. It was thought that the substance of the flight deck was sufficient to ward off penetration by lesser dive-bomber loads. Nonetheless, there is no doubt that dive-bombing was more precise and more effective with the same weight of bombs than any level-flight method employed for this purpose during the war.

The only Allied carrier (built after 1942) lost to deck hits by bombs was the American light carrier, USS Princeton (CVL-23). A IJN dive-bomber dropped a single bomb, which struck the carrier at a weak point between the elevators, crashing through the flight deck and hangar before exploding. Although 1,361 crewmen were rescued, 108 men from the Princeton were lost in the attack. The interior of the ship was said to have been an inferno. Many light and escort carriers were unarmored, with no protection on the hangar or flight deck, and thus they fared poorly against deck hits. The USS Franklin was struck by two 250 kg (550 lbs) bombs, one semi-armor piercing (SAP) and one general purpose (GP) bomb, both of which penetrated into its hangar deck and set off ammunition there, killing 724 and wounding 265 of the crew. The ship survived and was decommissioned in 1947.

The unarmored American carriers of the Essex class suffered very high casualties from serious kamikaze hits for which no one had provided. The kamikaze threat was serious (173 recorded strikes on US vessels alone), but allied AA defences neutralized it somewhat. US carriers and their fighters shot down more than 1,900 potential suicide aircraft. Many kamikaze strikes missed the deck armor entirely, or bounced off the decks of both British or American carriers. After a successful kamikaze hit, however, the British were generally able to clear the flight deck and resume flight operations in just hours, while the Americans in some cases took a few days or even months to affect repairs. The USS Bunker Hill was severely damaged by a pair of kamikaze hits that killed 346 men. In total, four US carriers suffered significant damage from suicide planes.

The Royal Navy and IJN limited their carriers’ aircraft capacity to the capacity of their under-deck hangars, and struck down all aircraft between operations. The US typically used a permanent deck park to augment the capacity of their aircraft carrier’s hangars giving them a much larger aircraft capacity than contemporary Royal Navy armored flight deck carriers.