Foreign cultural influences shaped Mexican attitudes as much as capitalistic economic constraints and diplomatic pressures from London, Paris, or Washington. The Catholic Church, dominated as it was by Spanish clergy, preached its mantra of a revival of European piety based on the iron dogmas of the Counter-Reformation. With it came an insistence on the preservation of Spanish social, racial, and gender hierarchies, as well as the unfounded, but inspiring and romantic, ideals of Hispanidad; that is, that groups of Spanish speakers formed an almost biologically separate ethnic group in the world. Mexico was included in nineteenth-century global efforts by the Catholic Church to deter believers from falling under the influence of new and attractive ideologies, such as the natural sciences and Marxism. This also meant a silent papal tolerance for a new, more radical Catholic labor organization that also addressed the inhumane working conditions of industrial workers in cities such as Puebla and Monterrey. Mexican anarchosyndicalists, cheered on by Spanish and Italian friends, were no longer the only ones attacking the problem.

In the few large urban centers, upper-class Mexicans continued efforts to construct and then impose one national culture based on European mores on the obstinate large majority who wanted none of it. Sometimes this meant promoting Italian opera and imitating Parisian dress codes. At other times it appeared in the form of promoting new behavioral norms at small industrial shops and, on occasion, as a frontal attack against Catholic holidays by less pious but more entrepreneurial modernizers. The Porfirian government backed this battle for the hearts and minds of mestizos with architecture competitions for federal buildings and designs for historical monuments and stamps. Even the national archaeology and international fairs were employed for this purpose. The elites expected that these new cultural rituals and their accompanying blatant government symbolism would transform the nation from a composite of many diverse geographical areas, dominated by Mexico City, into one nation that had left its Native American legacy behind and functioned increasingly according to European positivist standards.

Rural people stubbornly undermined these high-class flirtations with foreign ideas by creatively disregarding them culturally, as well as by staging the occasional riot. The majority of the rural population did not want to become modern, rejected the emotional adjustments that came with the industrial lifestyle, and laughed at French aesthetic ideals. All the tensions created by the contradictions of the thirty-five years of Porfirian developmental policies connected more and more Mexicans through frustration. By 1910, all classes were certain that the government and its president had to change.

Most contemporary foreign observers did not understand the profound depth of the nation’s contradictions. Whatever political tensions and accompanying rebellions occurred during the electoral game in 1910 between Porfirio Díaz, Bernardo Reyes, and Francisco Madero, foreign observers interpreted them as something that could be expected in a cultural and political setting they considered deeply uncivilized. They noticed the higher-than-usual number of local rebellions in the north, Zapatista fights against sugar plantation owners in Morelos, and the suppression of urban revolutionary conspiratorial cells in the cities. Nevertheless, they consoled themselves with the cliche that these, too, comprised just one more “Latin American uprising.” Owners and managers of foreign companies saw these challenges to Díaz, first, as an opportunity to expand their economic turf. Second, it was argued, disgruntled and disunited elites might be willing to make new concessions to foreign economic interests and perhaps reduce the influence of rivals. For example, U.S. oil interests reinforced Madero’s reservations about British oil. By coincidence, this sentiment translated into a rise in German financial influence within the strengthening Madero camp. Not surprisingly, British and French companies backed the status quo, hoping that the iron fists of Porfirian soldiers and rural militias would eventually overturn U.S. and German gains.

In contrast, the leaders of regional revolutions were much more realistic about their links with foreign interests. For Pancho Villa, access to the U.S. hinterland guaranteed the flow of American weapons to his and other Chihuahuan rebels. For Madero, temporary exile in San Antonio, Texas, provided safety and the chance to reorient his previously reformist urban political challenge to Díaz toward an alliance with the rebels in Chihuahua. He was helped by Felix Sommerfeld, who dabbled in several regional secret services. The Zapatistas in Morelos distinguished themselves through their lack of foreign support and therefore felt the full brunt of governmental repression in a race war without end in Morelos. Ironically, in Yucatán the profitable links with agricultural markets in the United States and Europe cemented the social and political status quo, therefore avoiding the outbreak of open sustainable revolutionary movements among Mayan debt peons.

Along the U.S.–Mexican border, rebels appreciated how foreign money, weapons, and access to a logistical hinterland could be as important as ideology and social bonds, if their rebellions were to last longer than a few days and stand a chance against the government in Mexico City. For the counterrevolutionaries in Mexico City, control over the ports in the Gulf of Mexico and continued tax income from the British petroleum industry provided sufficient money to initiate a hastened modernization and military deployment.

The political collapse of the Porfiriato in 1911 and the reluctance of revolutionaries in all regions to trade in their weapons or join the federal army of Madero’s newly created government suggested to domestic and foreign observers that something radically different was happening. Clearly, these developments were more than an average rebellion or a fight between national rivals that could usefully be exploited by foreign business interests. Foreign interests and domestic elites alike agreed that the continuously expanding power of the lower classes and their unchanneled, increasing political activity needed to be stopped.

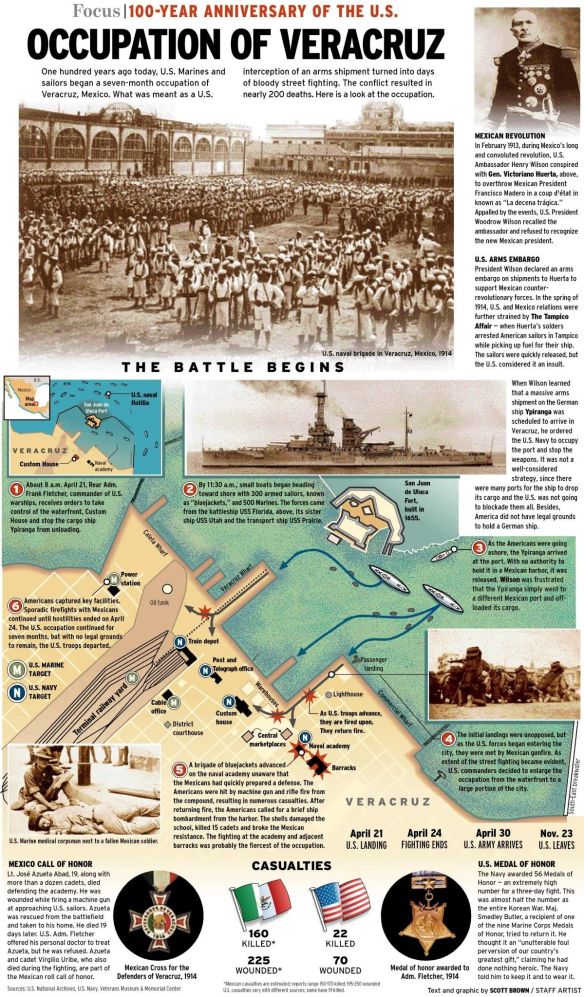

Suggestions for solutions to “the problem” differed sharply from camp to camp. European governments and company representatives favored straightforward repression and, unsurprisingly, backed the person they saw as the neo-Porfirian counterrevolutionary, Victoriano Huerta, against the rebels. In the middle stood U.S. ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, who mostly followed his own objectives and disregarded the directives of the newly elected Woodrow Wilson. He played a critical part in enabling General Huerta to realize a coup against Madero, and in Madero’s assassination, along with his vice president.

In Washington, D.C., President Wilson began to see Mexican developments as an example for his idealistic, yet naive, efforts to turn Latin America into a democracy. After several months of failed efforts to gain control over Huerta or at least to reach a modus vivendi with him, President Wilson became a determined opponent of Huerta’s emerging military dictatorship. Left with few alternatives, Wilson shifted his support to the revolutionary coalition of the Constitutionalists in the north. Wilson’s idealism had elevated the conflict into a regional Latin American issue.

In 1914, the outbreak of World War I in Europe and the accompanying establishment of the British economic blockade of the Atlantic Ocean again reframed the international context of the Mexican Revolution. For Europeans, Mexico’s oil reserves and its proximity to the United States suggested a manipulation of the revolutionary factions as an indirect tool to deprive their enemies of valuable strategic resources and manpower for future battles. For example, German war planners theorized and experimented with how a possible U.S.–Mexican war might tie up U.S. troops on a Mexican battlefield and thus guarantee the continuation of U.S. neutrality in World War I. Also, sabotage in the oil fields could deprive the British navy of an important source of fuel for its defense against Germany. In turn, British war planners debated how they could protect British oil production in Mexico against German attacks without inviting rival U.S. companies to exploit such a clash. For the British navy, a critical issue was how to maintain control over Atlantic shipping routes, so that it would not be deprived of a critical fuel source.

The British pondered the issue of whether and how to drag the United States out of neutrality and into the war on its side. Having the United States as an ally would certainly tip the strategic balance against Germany within months. U.S. planners watched with growing concern the activities of German and other European agents in the various revolutionary camps. For different reasons, the continuation of the Revolution was in the interest of all the major foreign powers. By then, the domestic conflict had developed new international dimensions as a bilateral U.S.–Mexican issue, a Latin American concern, and an increasingly important sideshow for European and U.S. military strategists.

The revolutionaries recognized their growing importance and, in turn, tried to sell their involvement as expensively as possible. Short-term military gains began to replace national long-term political plans. For the Constitutionalists, the internationalization of the Revolution offered critical foreign allies in their fight against the Huerta dictatorship in Mexico City. When the U.S. ordered a limited intervention in 1914 in Veracruz, President Victoriano Huerta suffered a decisive humiliation. Eventually, the combined pressure of domestic revolution and U.S. opposition forced him to abandon his attempt to turn back the political clock in Mexico. The internationally sensitive situation demanded that President Wilson engage in political negotiations with every major revolutionary faction to determine Huerta’s successor. In the end, the expanding world war and the links of its European players with anti-U.S. revolutionary factions made it impossible for U.S. planners to pick a Mexican president. Instead, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile acted as mediators in the ensuing competition over the presidency. Presidential selection issues would not again have such a strong role in the hemisphere until the 1990s. The unexpected winner was the nationalist politician Venustiano Carranza, certainly not a comfortable candidate for Wilson. After Carranza’s rise to the presidency, the nature of the Revolution changed into a civil war fought between factions of the previous anti-Huerta revolutionary coalition. In addition, regions that had not participated in the Revolution were occupied by the Carrancistas and forced to bring their regional politics and economics in line with the changes in Mexico City.

The intensification of fighting offered more options for renewed behind-the-scenes European and U.S. manipulations. Pancho Villa felt so betrayed by Wilson’s reluctant but expanding support for the Pax Carranza that the Chihuahuan decided to violate U.S. territorial sovereignty and attack the small border town of Columbus, New Mexico, on March 9, 1916. Villa hoped both to bring about a shift of popular nationalist support away from Carranza and to provoke the United States into invading Mexico. Immediately, a U.S.–Mexican war would demonstrate the limits of Carranza’s power vis-à-vis the United States. Villa expected that Carranza’s predicted helplessness could bring about a revival of Villa’s rebellion in the north. He expected to fight simultaneously against Carranza and the United States and to reenter the battle for the presidency.

Villa’s actions failed to provoke a full-fledged U.S.–Mexican military confrontation. Yet angry U.S. popular opinion demanded from President Wilson some public action against Villa’s violation of U.S. territory and the murder of U.S. citizens. Wilson chose to placate popular anti-Mexican sentiment by sending General John J. Pershing and ten thousand soldiers on a punitive expedition into Chihuahua with the task of capturing Villa. During the following months, Villa eluded U.S. pursuers in the impenetrable mountains of Chihuahua. More important, Carranza turned the crisis in his favor. An unexpectedly aggressive diplomacy and a confrontational press policy, as well as determined Mexican soldiers at the Carrizal garrison, who fought one battle against Pershing’s troops, brought about the withdrawal of U.S. forces. General Pershing’s failure was somewhat hidden by the year-long expedition in Chihuahua, followed by an impressive but unjustified triumphal return to U.S. territory. The relationship between Carranza and Wilson received lasting damage. Carranza recognized that in the years to come, he could not expect any U.S. financial or political help for the reconstruction of his nation. Thus, ironically only Germany, if it had won the war, could have been a possible friend to Carranza’s government.

The emergence in 1916 of unrestricted naval warfare among Germany, Britain, and the United States only confirmed the continuing international significance of the Mexican conflict for the European great powers. Germans pondered how to entangle U.S. resources in the Americas so that they could not be deployed on European battlefields. One option under consideration was the creation of a German–Mexican military alliance that would turn Mexico into enemy territory for the United States. Germany tried to entice Carranza into considering the offer seriously. In February 1917, the Germans promised him as a reward the return of territory lost to the United States as a result of the U.S.–Mexican war, after a victorious conclusion of World War I. When the discussion of the offer between German Minister to Mexico von Eckhardt and German Undersecretary of State Zimmerman was intercepted by British and U.S. intelligence forces, luck provided the Allied powers with a propaganda weapon that would be remembered throughout the twentieth century. The revelation of the German scheme proposed in the so-called Zimmerman Telegram reinforced deep suspicions among Washington policy makers about Carranza’s loyalties and the possible motives behind his nationalism. Not surprisingly, Carranza’s insistence on Mexican neutrality during the war was interpreted in the U.S. Congress as nonbelligerency on behalf of Germany. It helped Wilson to gain support within U.S. Congress for entry into World War I in April 1917.

Carranza did not confuse German promises of involvement in case of a Mexican–U.S. war. He wanted confirmation that the Germans saw in Mexico more than the back door to the United States, a potential strategic hinterland, and an ideal staging ground for secret attacks that exploited Mexico’s continued neutrality. In June 1916, the German government admitted its inability to give Carranza what he needed most: gold to stock an independent Mexican national bank. Carranza became more selective in German partners but continued relations with a small number of critical individuals. He could not simply reject German approaches. Any openly negative attitude toward Germany might encourage Berlin to abandon careful consideration of Mexican sensitivities and initiate sabotage activities in the oil fields. Most likely, sabotage in the petroleum industry would trigger a U.S. intervention that would reduce Mexico to a battlefield between Allied–German militaries. For the remainder of World War I, German–Mexican relations remained officially friendly and engaged. Von Eckhardt helped Carranza with intelligence information about Allied agents. In late 1917 and 1918, he encouraged Carranza’s representative, Isidro Fabela, to move among Mexico City, Buenos Aires, and Madrid, exploring whether German government support could make the revolutionary chief financially independent from Allied banks. Mexican agents became friendly with German and Japanese agents, working against the United States in South America. A few Japanese Navy leaders were pursuing arms sales relations with Carranza that the Japanese emperor ignored. Rightly so, in Washington, U.S. observers followed German–Mexican–Japanese interactions as a national security issue and considered the possibility of confronting German forces inside Mexico. Outstanding U.S. intelligence work prevented a major 1918 German sabotage campaign in the United States planned in Mexico City.

Select Mexican, German, and Japanese activities against the United States continued after the November 1918 armistice. Because French and U.S. policy isolated revolutionary Mexico, Carranza attempted to unify anti-U.S. groups in Latin America, trying to defeat the launching of the League of Nations. In addition, he negotiated with Spanish, Belgian, Italian, and Austrian arms manufacturers to build an independent Mexican arms industry that could supply his forces in a potential future war against the U.S. Army. Carranza’s assassination by political rivals in 1920 eliminated this major Latin American nationalist from the anti-U.S. political scene, exceeded in scope and skill only by Fidel Castro in the 1960s. Still, only the successful 1921 Washington Naval conference turned a strengthening Mexican, Japanese, and German intelligence exchange from a gathering threat into a historical curiosity.

In retrospect, Carranza deserves to be recognized as one of Mexico’s greatest foreign policy makers of the twentieth century. Under the most difficult revolutionary circumstances, he succeeded in keeping his country and its citizens out of direct military involvement with both the German and the Allied sides during World War I. His skillful diplomacy prevented a devastating U.S.–Mexican war or a longer U.S. military presence on Mexican soil. Meanwhile, he succeeded in assuring Germans of enough Mexican interest in future cooperation to avoid sabotage of the British and U.S. petroleum industries in Mexico. He also isolated Villa in Chihuahua and kept German manipulators at arms length. Finally, he confronted U.S. President Wilson vigorously through diplomacy, propaganda, and the symbolic display of military courage. In the midst of this explosive situation, he and representatives of other revolutionary factions passed the Constitution of 1917, which created the legal foundation for subsequent presidents to achieve sovereignty over national territory and natural resources.

Publicly, Carranza preferred to talk only about a set of political principles—later called the Carranza Doctrine—that guided foreign relations through several decades of the twentieth century. Its most important points were the rejection of the Monroe Doctrine, a demand for foreign respect in regard to Mexico’s economic and territorial sovereignty, an insistence that all foreign powers accept the concept of nonintervention in Latin America, and, finally, an emphasis on the importance of negotiating alliances with European and Latin American countries that could counterbalance Mexico’s geographic fate of bordering on the United States. Under the most difficult domestic and international circumstances, Carranza had broken with Porfirian laissez-faire and established a distinct nationalistic revolutionary agenda that sought domestic solutions to the international challenges of expanding capitalism and centuries old great-power rivalries in Europe.

Carranza’s dogmatic insistence on self-definition turned out to be timely. Following World War I, the United States replaced Great Britain as the most important economic and political power in Latin America. The newly founded League of Nations recognized the application of the Monroe Doctrine, refusing to aid Latin American countries against short-sighted and amateurish U.S. policies of big-stick and dollar diplomacy during the Republican presidencies of the 1920s.

By 1921, Villa’s retirement from revolution, the assassinations of Zapata and Carranza, and Wilson’s retirement from the White House provided a new opportunity for Mexican and U.S. representatives to forge a closer, more constructive relationship. Yet the next four years remained as difficult for the emerging revolutionary state as the previous years had been.

In a sharp break with Wilsonian universalism, Harding brought relief from the naive perception that democracy could be decreed overnight in Mexico. Other possible benefits from the United States’ turn toward isolationism did not materialize. U.S. racial discrimination against Mexicans continued and even intensified within the context of the xenophobic immigration debates of the 1920s. The Republican political and economic laissez-faire stance only made U.S.–Mexican bilateral relations more difficult. Now that the U.S. government was only one among many laissez-faire political interests in Washington, U.S. contacts with Mexico diversified to the point of destructive chaos.