To implement the strategy outlined in the Anaconda Plan, the Union army had to raise thousands of volunteer troops and outfit, train, and transport them to theaters of war. In the case of the western theater, they had to be marched overland or conveyed by rail and river steamer to staging areas such as Cincinnati or Cairo. To transport men and supplies and to secure control of the Mississippi and other western rivers, the Union navy had to lease, purchase, or construct a flotilla of steam-powered vessels suitable for operations on these narrow, shallow rivers. The navy had to protect the vital areas of these river craft from shot and shell, and it had to arm these newly constructed or acquired vessels with modern ordnance and staff them with officers and men.

Creating a brown-water navy almost from scratch called for innovativeness. The first steamers acquired by the Union navy for western service in 1861—the A. O. Tyler, Lexington, and Conestoga—were converted from commercial side-wheel steamers. Protected by five-inch timber bulwarks, they were, as one officer remarked, unprotected against “anything more formidable than musketry.” However, these ungainly looking timberclads proved their worth at the battle of Belmont and continued to serve the flotilla at Forts Henry and Donelson, during the battle for Shiloh, on the Yazoo River, and in the lower Mississippi.

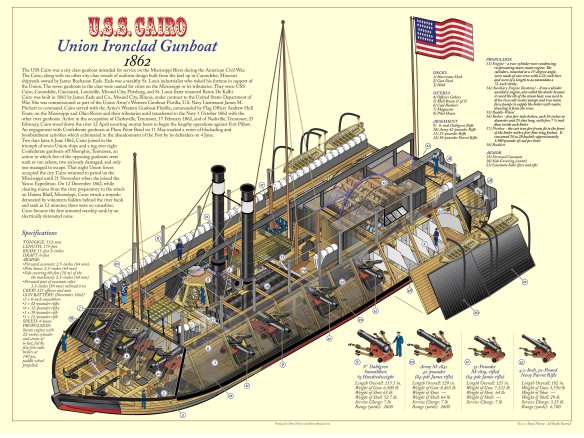

The timberclads were followed by a class of warship specially designed for service on western rivers. The seven city-class ironclads—the Cairo, Cincinnati, Carondelet, St. Louis, Mound City, Louisville, and Pittsburg—completed in 1861 extended the navy’s capabilities and made a vital contribution to the war in 1862 and well into 1863. The new ironclads’ sterling performance in their baptism of fire at Fort Henry had the unfortunate consequence of convincing many that these Pook turtles were invincible, but Fort Donelson’s gunners disabused them of that notion. The city-class ironclads were, indeed, vulnerable to enemy fire. In a running fight with CSS Arkansas, for example, the Carondelet sustained considerable damage, one 8-inch shot striking it in the stern, gutting the captain’s cabin, and knocking a twelve-inch oak log into splinters.

Despite being struck repeatedly by enemy shot and shell in engagements with Confederate gunboats, rams, and fortifications, the Pook turtles were remarkably sturdy vessels, and several that were damaged or disabled underwent repairs and returned to service. On the St. Louis, casemates greased with tallow deflected enemy shot from Fort Hindman, but the gunboat suffered casualties when shot entered its gun ports, and one that landed on the muzzle of a 10-inch gun caused an explosion. Three other city-class ironclads were eventually lost: an enemy mine sank the Cairo in December 1862, a boiler explosion caused by enemy shot claimed the Mound City, and, pummeled by enemy fire at Vicksburg, the Cincinnati sank.

The next large ironclads constructed by the Union navy for western service—the rams Lafayette and Choctaw—were better able to withstand enemy shot and shell. Although hit nine times while passing the Vicksburg batteries, the Lafayette suffered little damage. The Choctaw, converted from a side-wheel river steamer, had one-inch armor over one inch of India rubber, but the rubber proved useless, and the armor and armament were too heavy for the hull. Nonetheless, the ironclad served at Haynes’ Bluff on the Yazoo in May 1863, sustaining eighty-one hits, and then went on to participate in the Red River expedition.

The Chillicothe, commissioned in September 1862, followed by the Tuscumbia and Indianola, commissioned in January 1863, were smaller and had an unusual arrangement of machinery consisting of both side wheels and screw propellers; they were armed with 11-inch smoothbores. A Confederate vessel rammed the Indianola near Vicksburg in February 1863, running it aground. The Tuscumbia proved far sturdier, being hit eighty-one times during the bombardment of Grand Gulf. Rebel gunners at Fort Pemberton on the Yazoo River aimed their fire at the Chillicothe, putting a shot through the bow gun port as the gun was being loaded, and both exploded. After repairs, however, the Chillicothe returned to the squadron in September 1863.

The most formidable ironclad in the Mississippi Squadron was the Essex, formerly the snag boat New Era. It was acquired in the fall of 1861 and converted by Eads into a timberclad, then an armored vessel with three inches of iron on the casemates. The Essex served in the Cumberland River expedition and at Fort Henry, and it took part in the attacks on CSS Arkansas. A lucky shot hit the Essex at Fort Henry and caused a boiler explosion, but commanding officer William Porter had the vessel repaired and upgraded, enabling the ironclad to support the bombardment of Port Hudson and the 1864 Red River expedition.

The Mississippi Squadron’s flag boats, the Benton and Black Hawk, were also converted to ironclads from river steamboats. The Benton, though formidably armed, was not impervious to shot and shell. Enemy fire roughed the vessel up at Grand Gulf and in the Yazoo, and in July 1862 a shot from an enemy Whitworth rifle went clean through the bow, exploding and injuring several sailors.

The little gunboats dubbed tinclads—the Marmora, Signal, Rattler, and Red Rover—were not yet in service and thus did not take part in the battles for New Orleans or Memphis or in the engagements with the Arkansas, but they made valuable contributions to Union naval operations on the Mississippi, Ohio, Tennessee, Cumberland, Yazoo, and Red Rivers. Designed to patrol shallow, twisting western rivers, they were converted from steamboats by the addition of thin boilerplate iron as armor. The Union produced sixty-three of these tinclads during the war, and they served admirably, fighting rebel sharpshooters, enforcing revenue, and acting as towboats and dispatch vessels.

During the Vietnam War, the US Navy looked back to these unique river craft and designed or converted similar, lightly armed vessels to patrol the Mekong Delta. For example, the 130 PBR Mark 1 patrol boats deployed for Operation Game Warden were modified commercial sports craft ordered in 1963 from American builders; they were armor plated and armed with three .50-caliber machine guns and a 40 mm grenade launcher.

In addition to these navy craft, in 1862 Charles Ellet developed steam-powered rams by purchasing river steamers and reinforcing their hulls and bows with timber. The Army Quartermaster Department converted the Lioness, Lancaster, Mingo, Queen of the West, Switzerland, and Monarch. Ellet formed a command that was independent of the navy, but his rams took part in the battle of Memphis and passed the gauntlet of fire from the Vicksburg batteries.

To bombard Confederate batteries, especially those positioned on bluffs above the Mississippi River, the Union navy turned to the army’s 13-inch seacoast mortars. The Western Gunboat Flotilla ordered flat-bottomed rafts to carry these monstrous mortars and manned them with fifteen-man crews. Lacking their own propulsion, the mortar boats had to be towed into position. Initially, the new mortar boats went into action against Confederate batteries at Island No 10. Foote had great confidence in the effectiveness of the new boats and told his commanders to “let the mortar boats do the work.” They could not, however, silence the rebel defenses. In the battle for New Orleans, Porter deployed twenty-one 13-inch mortars placed on mortar schooners. Firing every ten minutes, the mortars pounded Fort Jackson, setting fire to the citadel, but enemy fire managed to damage two of the schooners. When Farragut and Davis met at Vicksburg in July 1862, Porter’s mortars were placed along the riverbanks in the hope they might reduce some of the enemy defenses. Sailors like coxswain John Morison of the Carondelet continued to have faith in the efficacy of these mortars, but orders from Secretary Welles sent Porter and twelve of the mortar boats back to Hampton Roads.

Porter continued to believe in mortars, and when he assumed command of the Mississippi Squadron he took mortars to the Yazoo in December 1862 to support the army’s assault at Chickasaw Bluffs. Mortar boats also participated in the fifty-two-day bombardment of Fort Pillow, and by April 1862, they had fired 531 of these 13-inch shells. Mortars played an important role in the prolonged siege of Vicksburg as well, augmented by naval guns brought ashore to bombard the rebel fortifications at that stronghold.

Although typically used to bombard enemy batteries on bluffs, owing to their arching fire, the Union navy occasionally employed mortars against enemy vessels. The most famous incident involved Mortar Boat No. 16, which had only its mortar to defend itself against a rebel attacker. Mortar schooners also fired on the CSS Arkansas.

Union navy mortar boats were plagued by bad fuses, and because long-range, direct fire requires sophisticated fire control, their 13-inch shells had a limited impact on rebel batteries. Although the Union navy continued to employ mortars against enemy fortifications along the Mississippi River, these mortar boats never lived up to the navy’s expectations for them.

The Western Gunboat Flotilla, renamed the Mississippi Squadron in September 1862, took part in three engagements with Confederate naval forces and repeatedly dueled with rebel gun batteries and riverfront defenses. In addition, the Confederate navy initiated construction on several ironclads and put together a Confederate River Defense Force of rams and “cotton-clad” gunboats. Yet there were only two confrontations between Union and Confederate forces that could be classed a general fleet action. The first engagement took place off Plum Point above Memphis. In this “sharp but decisive” engagement with the Confederate River Defense Force in May 1862, the federal squadron parried the rebel rams, but the Cincinnati and Mound City suffered serious damage before the Yankee boats retreated to shallower water and the Confederates withdrew. Then, when Davis’s flotilla met Confederate rams above Memphis, it was Ellet’s rams Queen of the West and Monarch that boldly dashed past them to take on the enemy.

Union gunboats, mortars, and rams also bombarded and exchanged gunfire with Confederate forts and gun batteries on numerous occasions. The first was the battle of Belmont, when Walke’s timberclads fended off rebel fire. The Western Gunboat Flotilla moved down to Paducah and then to Forts Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Cautiously advancing against Fort Henry’s eleven river-facing guns, the four Eads ironclads encountered less than robust return fire from the rebel batteries, as those at water level had been rendered useless by flooding. All the ironclads were hit by rebel shot and shell but sustained no serious damage, and Fort Henry’s defenders surrendered before Union troops could make an assault, handing Foote a victory. When most of the enemy troops withdrew to nearby Fort Donelson, that became the flotilla’s next objective. There, the ironclads closed Confederate batteries positioned on bluffs above the river, allowing rebel gunners to pour plunging fire down on them. Unable to elevate their guns to return fire, the Pook turtles took a beating.

The flotilla’s pummeling at Fort Donelson made Foote cautious about exposing his ironclads to enemy batteries at Island No. 10—until Walke agreed to run the Carondelet down past them under cover of darkness. Farragut had less compunction about Confederate river defenses and took his Gulf Squadron past the forts at New Orleans, Vicksburg, Grand Gulf, and Port Hudson. Foote and Porter, Davis’s successor, confronted enemy batteries on the Yazoo River, at Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post, and at Vicksburg. The Mississippi Squadron, in fact, became the army’s “floating artillery.”

In many of these engagements with Confederate gun batteries, Union naval vessels came through relatively unscathed, despite being struck repeatedly. As the war progressed, commanders learned that coiling chains, placing hay or cotton bales on deck and near bulwarks, or greasing casemates with tallow helped protect their vessels from shot and shell. During the attack on Fort Hindman, for example, enemy shot struck the Cincinnati at least eight times but simply bounced off the greased casemates.

Chains and tallow could not always protect a vessel’s boilers, and pilothouses were vulnerable as well. Union ironclad gunboats and rams were conned from pilothouses sheathed in iron plate, but the pilothouses were often targeted by enemy gunfire, and when shot or shell penetrated them, the splinters could inflict serious damage and casualties. When officers stepped outside these pilothouses, they risked injury, as Roger Stembel learned when a rebel sharpshooter’s bullet struck him during the battle of Plum Point.

Whether down on the gun deck or in the pilothouse, the officers and men of the Western Gunboat Flotilla risked death or injury from musketry, enemy shot, splinters, and gun or boiler explosions. The bursting of a rifle gun onboard the St. Louis on March 17, 1862, for example, killed two seamen and wounded fifteen. A similar gun explosion killed fourteen men on the Chillicothe in the Yazoo River. During the assault on Fort Donelson, a shell hit the Carondelet, killing four men and wounding the pilot and twenty-seven other crewmen. At Chickasaw Bluffs, the flagship Benton suffered twelve sailors killed, and in the assault on Arkansas Post and Fort Hindman, Porter’s flotilla incurred thirty-one killed and wounded in capturing that enemy strongpoint. Even one well-placed enemy shot could inflict devastating damage, as was the case with the Mound City.

Confederate gunfire did not discriminate. Foote suffered an injured foot, Stembel was shot by a sharpshooter, Augustus Kilty died from burns suffered in the Mound City boiler explosion, A. Boyd Cummings lost a leg, and William Gwin was mortally wounded. The ships and gunboats of Farragut’s fleet also sustained casualties during operations on the Mississippi River. Farragut’s squadron, for example, suffered five killed and sixteen wounded, and Davis’s Mississippi Squadron had thirteen killed and thirty-four wounded while passing the Vicksburg batteries.

Combined operations in the West during the Civil War required senior army and navy commanders working together to formulate strategy and to allocate troops and resources. Cooperation with the Union army proved essential in the assaults on Confederate strongholds at Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and Grand Gulf. Naval gunboats and mortars shelled these fortifications, attempting to silence the rebel batteries, but in many cases it took federal troops—“boots on the ground”—to assault, occupy, and hold these positions. The Union army’s failure to allocate sufficient troops could doom these combined operations to failure, as was the case with the first Vicksburg campaign.

In addition to Confederate gun batteries and naval forces, Union naval units faced opposition from rebel sharpshooters, from irregular Confederate troops or guerrillas, and from a new weapon—the “torpedo,” or mine. From almost the beginning of the war in the West, Union naval vessels, army transports, and other river steamers found themselves under fire from local pro-Southern citizens, armed bands, and Confederate guerrillas. Walke’s flotilla at Milliken’s Bend repeatedly encountered enemy sharpshooters, and sharpshooters harassed Porter’s vessels during the Steele’s Bayou expedition as well. In fact, guerrillas visited the banks of the Mississippi with impunity, took potshots at passing transports, and seized the Sallie Wood. When federal rams or gunboats pinpointed these enemy guerrilla bands or rebel artillery pieces, they did not hesitate to lob a few shells at them, as the Lancaster did against one band of rebels. The Forest Rose surprised a guerrilla camp on the Yazoo, and in some cases the army landed men to pursue guerrillas. Towns were not spared the federals’ wrath either. When rebel guerrillas fired on a dinghy from Farragut’s flagship Hartford off Baton Rouge, the ship’s gunners immediately retaliated by firing into the town. None of these guerrilla attacks on Union naval vessels inflicted serious damage or caused a large number of casualties, but they did force commanders to use caution and in some cases to carry their own sharpshooters on board.

The Confederacy contested Union naval operations on the Mississippi, Cumberland, Tennessee, and Ohio Rivers with both steam-powered rams and gunboats, but also with a new weapon: the “torpedo,” or mine. These “infernal machines” proved capable of causing serious damage to federal gunboats, sinking the USS Cairo in December 1862. Dragging for floating mines became one of the Yankee flotilla’s ongoing missions, consuming time and manpower. Furthermore, mines could render stretches of the river unsafe for federal gunboats, curbing their ability to provide fire support to the army.

The Mississippi River itself proved a challenge to Union naval operations and sometimes seemed to be the “enemy.” The Mississippi River rose with winter and spring rains, causing extensive flooding; then it fell with the approach of warm weather. Low water proved hazardous to Farragut’s deep-draft wooden vessels. The Hartford grounded on its way north, and many others, even lighter-draft gunboats such as the Winona, also went briefly aground. Federal vessels also risked damage from snags or sawyers, collisions, and falling trees, and the swift current in these narrow western rivers made positioning the gunboats to bombard enemy positions difficult.

Manning the burgeoning number of ironclads and gunboats of the Western Gunboat Flotilla proved even more challenging than constructing or converting them. Foote repeatedly asked the Navy Department to send him men to fill out the complements of new vessels and to replace men whose terms of enlistment had expired or who had fallen ill. The Union navy competed with the Union army for recruits, and when recruiting efforts failed to produce enough seamen, the navy turned to foreigners, African Americans, and Confederate prisoners of war who were willing to enlist. As a last resort, commanders asked the army to detail soldiers to serve on naval vessels.

When federal gunboats appeared on the Mississippi River and its tributaries, African Americans, most of them slaves belonging to plantations situated on these waterways, often greeted them warmly. Some of them offered to provide food or information about Confederate activity or to act as guides. Soon, increasing numbers of slaves, and even some free blacks, began to seek safety on federal vessels. Naval commanders did not always oblige these fugitives, but they gradually came to value the intelligence they provided about the enemy. They employed these contrabands as crewmen, stevedores, and laborers, and the women worked as cooks, laundresses, and aides in Union hospitals and aboard hospital boats such as the Red Rover.

Union navy policy toward African Americans in the West varied over time. In deference to the bias of the Southern people, Foote did not want contrabands shipped on his vessels, and the enlistment of blacks had to wait until April 1862. Porter issued regulations to segregate blacks in his crews; they were to be “messed by themselves and also [to] be kept in gangs by themselves at work.” But segregation on shipboard was not always possible, and Porter finally had to admit that his contraband sailors “do first rate.”

In the summer of 1862 the army employed a large force of slaves, along with some troops, to dig a canal across the peninsula opposite Vicksburg. When Davis and General Williams departed, scores of African Americans who had dug the canal were left behind, denied their promised freedom. Sherman, however, welcomed slaves as laborers, putting them to work and housing their families. In the fall of 1862 he ordered that runaway slaves be treated as free, pending a final ruling by the courts. This opened the “floodgates of freedom,” and the fugitive population grew sharply as a result.

African Americans seeking sanctuary on Union vessels presented commanding officers with opportunities, but also with the challenge of feeding and protecting them. Many were sent ashore to army commanders, but the navy retained the able-bodied males as first-class boys, coal heavers, and landsmen. By the summer of 1862, many Union warships, rams, and gunboats had African American crewmen. Black sailors fought alongside their white comrades on Union vessels and risked injury and death. One contraband had both his arms and a leg shot off while serving on the ram Lancaster. Shot and shell from the Arkansas also injured seven black deckhands and coal heavers.

When the Union army recruited African Americans as troops and deployed them in the Mississippi Valley campaigns, Union gunboat commanders were asked to support these black soldiers and defend them against enemy attack. The extent to which African Americans, slave or free, supported the Union war effort in the West has not been extensively studied, but as this narrative of Union naval operations on the Mississippi River has shown, African Americans made substantial contributions to the Union navy’s opening of the river.

Union navy vessels operating on these western rivers did incur combat casualties, but more officers and men suffered from various illnesses. Fevers and gastrointestinal illnesses often drastically reduced the number of seamen fit for duty on navy vessels. When the Carondelet met the CSS Arkansas, for example, half its crew were ill, and Walke could man only one gun division. Foote himself succumbed to an injury and the debilitating effects of the Southern climate. Watson Smith asked to be relieved of command of the Yazoo expedition because of an unspecified illness, possibly suffering a nervous breakdown.

Naval operations on the Mississippi River involved transporting these ill and wounded sailors and soldiers from the battlefields to hospitals in Memphis and Cairo. Numerous cases of fever and other illnesses prompted the Union navy to outfit river steamers as hospital boats, the Red Rover being the most famous example. Naval gunboats also carried prisoners north to Union prison camps or escorted vessels carrying flags of truce or conveying prisoners of war for exchange.

Service in the brown-water navy was not glamorous duty. As one historian put it, “the brown water sailors of the riverine war struggled like their army comrades with a hostile, combatant populace, disease, boredom, and death in the shadows from marksmen known as bushwhackers.” The almost two-year battle to implement Scott’s Anaconda Plan to “open the Mississippi River” might not have succeeded without the brown-water fleet. As Admiral Porter wrote, “The services of the Navy in the West had as much effect in reducing the south to submission as the greater battles fought in the East.”