On 22 March, the remnants of the 6th SS Panzer Army withdrew towards Vienna. By 30 March, the Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front crossed from Hungary into Austria. By 4 April, the 6th SS Panzer Army was already in the Vienna area desperately setting up defensive lines against the anticipated Soviet Vienna Offensive. Approaching and encircling the Austrian capital were the Soviet 4th and 6th Guards Tank, 9th Guards, and 46th Armies.

The use of the 3rd Ukrainian Front’s tank forces during the March battles is of interest. It had been planned beforehand to use the tanks and self-propelled guns in order to strengthen the defense on prepared lines, and with the start of the German offensive, the tank formations were moved up to these lines.

The tactics of strict defense were adopted by the tank and self-propelled guns – the armored vehicles were dug into the ground among the infantry’s combat positions, or else kept concealed in ambush. In order to facilitate a more responsive command arrangement over the tank formations, they transferred from subordination to the Front to the control of the army commanders.

The tank’s combat formations on the defensive depended on the situation and the assignment. For example, the 18th Tank Corps, having taken position among the combat positions of the infantry south of Seregélyes, assigned each tank brigade its own sector of defense, while the motorized rifle brigade was distributed by battalion among the tank brigades. The defense was organized around individual strongpoints, each of which had 2-5 tanks, a platoon of motorized infantry, and 2-3 guns.

The 18th Tank Corps was reinforced with the 207th Self-propelled Artillery Brigade of SU-100 tank destroyers, which took up positions by battery in the second echelon of defense. At the same time, the tank destroyers had prepared firing positions in the first echelon, to which they moved up during enemy tank attacks. All of this allowed the creation of a dense wall of anti-tank and antipersonnel fire in front of the 18th Tank Corps’ positions, and in the course of 10 days of savage fighting, the enemy was in fact unable to break through the defense in this sector.

Thus, on 7 and 8 March alone, units of the 18th Tank Corps knocked out or destroyed 33 German tanks and self-propelled guns. In return, their own losses amounted to a total of 16 tanks or assault guns, including 2 T-34, 2 ISU-122 and 3 SU-76 knocked out, and 6 T-34 and 3 ISU-122 burned out.

Part of the 1st Guards Mechanized Corps occupied positions in the Heinrich Estate, Sárkeresztúr, Cece, Sárbogárd area. Here the defense was organized around company-sized strongpoints, each of which contained 5 to 8 tanks or self-propelled guns. The strongpoints had standard trenches, machine-gun nests, dug-in combat vehicles, and anti-tank gun positions. The anti-tank guns moved up into their positions only in order to conduct fire, but spent the rest of their time in shelters. The SU-100 tank destroyer batteries were positioned in the second echelon, and with sudden counterattacks they would destroy the enemy’s tanks and halftracks.

Tank ambushes were widely and successfully employed. For these, groups of tanks and selfpropelled guns would take concealment on the flanks of the anticipated axis of advance of enemy tanks, calculating to take shots at their side or rear facing. Artillery guns were usually positioned in order to protect the tanks that were waiting in ambush. Combat experience demonstrated that when organizing tank ambushes, it was useful to use decoy tanks, which by their actions were supposed to lure the enemy armor into the flanking fire of the tanks concealed in ambush.

The 18th Tank Regiment of the 1st Guards Mechanized Corps, which was defending in the Sárkeresztúr area, adopted a rather curious tactic. When the regiment’s positions were attacked by up to a battalion of infantry, in order not to reveal the locations of the tank ambushes, the regiment commander Lieutenant Colonel Lysenko decided to counterattack the enemy with T-34 recovery tanks and armored halftracks. In this fashion, the tankers repelled two attacks by German infantry and took 35 Germans prisoner.

The SU-100 self-propelled artillery guns showed themselves to be quite effective in the March battles. In addition to the SU-100s of the 208th Self-propelled Artillery Brigade and of the two regiments in the 1st Guards Mechanized Corps, with which the 3rd Ukrainian Front started the battle, on 9 March the 207th (62 SU-100, 2 T-34, 3 SU-57) and 209th (56 SU-100, 2 T-34, 3 SU-57) Self-propelled Artillery Brigades arrived to join the Front. Upon their arrival, the 207th Brigade was sent to the 27th Army, and the 209th Brigade went to the 26th Army. Thus, by 10 March 1945, the total number of SU-100 tank destroyers in the area of Lake Balaton (after deducting the combat losses) amounted to 188.

These self-propelled guns were actively used on the defense in cooperation with the infantry in order to repel enemy tank attacks, as well as to cover the bridges across the Sárviz and Sió Canals. They proved quite effective in these tasks. For example, the 208th Self-propelled Artillery Brigade over the course of 8 March and 9 March knocked out 14 German tanks and self-propelled guns, as well as 33 enemy halftracks, while losing 8 SU-100 destroyed and 4 disabled.

In order to combat enemy tanks, the SU-100s primarily operated out of ambush positions. SU-100 batteries were deployed in covered positions, camouflaged in woods, or on the reverse slopes of hills and ridges. In front of them, at a distance of 100-200 meters, firing positions with good visibility and good fields of fire were prepared, and as a rule, they offered 360° of fire. In the positions or next to them, observation posts were set up, in which there would be an officer who had a communications link with the battery. Whenever German tanks appeared at a distance of 1,000 to 1,500 meters, the tank destroyers would move up into their firing positions, fire several rounds, and then use reverse drive to pull back into cover. Such a tactic justified itself when repelling enemy attacks in the areas of Sáregres and Simontornya. For example, on 11 March, a battery of the 209th Self-propelled Artillery Brigade’s 1953rd Self-propelled Artillery Regiment, having taken up an ambush position in a dense patch of woods west of Simontornya’s train station, repelled an attack of 14 German tanks, three of which were set on fire at a range of 1,500 meters.

The normal range for firing from the SU-100 at heavy German tanks was 1,000 to 1,300 meters, but out to 1,500 meters, and sometimes even longer, when firing at medium tanks and self-propelled guns. The SU-100s as a rule fired from fixed positions, but sometimes from short halts. From the indicated ranges, the SU-100 could inflict damage to all types of German armor, and as a rule, with the very first on-target shell.

Cooperation between the self-propelled guns and other units was implemented in the following fashion. The commander of the self-propelled regiment and the rifle regiment commander as a rule were located in the same observation post or had telephone contact with each other. The commanders of the rifle battalion and of a self-propelled gun battery would personally work out all questions of cooperation on the spot, and in case of need, also had telephone communications. The commander of the SU-100 brigade maintained constant radio contact with the commander of the rifle division to which his brigade was attached. This allowed the transmission of information regularly in the course of fighting and the reaching of necessary decisions.

Nevertheless, during the battle, a number of genuine miscalculations in the organization of cooperation with the SU-100s were revealed. For example, fire cover provided by the field artillery for the self-propelled guns was poorly organized, the infantry didn’t render assistance to the crews when attempting to pass through swampy areas of terrain, and several of the all-arms commanders tried to use the SU-100 in the role of infantry support tanks. For example, the commander of the 36th Guards Rifle Division ordered a battery of tank destroyers to lead an infantry attack. Because of the absence of infantry and artillery cover, the SU-100s came under the fire of German antitank guns, as a result of which three of the tank destroyers were left burning.

A substantial shortcoming of the SU-100, which was revealed in the course of fighting, was its absence of a machine gun. Because of this, the vehicle had no close range defense against infantry and proved defenseless against assaulting German infantry. As a temporary measure, it was proposed to give each crew a light machine gun, and to give 8-10 light machine guns to the company of submachine gunners in the SU-100 self-propelled artillery regiments.

In the first days of the German offensive, even training units were used to reinforce the Front’s tank units. For example, on 8 March, the 22nd Tank Regiment, which was formed from a training regiment with the same numerical designation, arrived in the 26th Army. In a report it was noted that “in view of the fact that the tanks were from the table of equipment of a training tank battalion and were located on a training ground and in a tank park, and as well of the fact that it was 115 kilometers to its assigned place of assembly, the regiment was 11 hours late in arriving.” Altogether, the 22nd Tank Regiment had 11 T-34, 3 SU-76, 1 SU-85 and 1 KV-1s. This unit conducted combat operations right up to 16 March.

As concerns the replenishment of materiel, over the period between 6 and 16 March, the 3rd Ukrainian Front received only one batch of replacement tanks and self-propelled guns – on 10 March, 75 SU-76, 20 Sherman tanks and 20 T-34 arrived from the rear. The self-propelled guns were used to replenish the 1896th, 1891st and 1202 Self-propelled Regiments, the 18th Tank Corps, and the self-propelled gun battalions of the 4th Guards Army, while the Shermans went to the 1st Guards Mechanized Corps and the T-34s went to the 23rd Tank Corps. In addition, a certain number of tanks were put back into service by the Front’s 3rd Mobile Tank Repair Shop. For example, on 6 March the 18th Tank Corps received 20 repaired T-34s from it.

The final German offensive of the Second World War was planned on a grand scale. However, even at this time – spring 1945 was already around the corner – many German calculations were based on an underestimation of the enemy’s possibilities.

In a tactical respect, the German panzer divisions proved to be much weaker than they had been in preceding operations, for example, in the January 1945 Konrad operations. Soviet documents on this subject stated:

If in the preceding operation the enemy had employed broad maneuvers with his mechanized troops, then in the given operation, the maneuvering from one sector to another was insignificant. The enemy fought on one axis using only separate groups of tanks shifted from one sector to another within the boundaries of the formation’s operations.

The defensive battles at Lake Balaton in March 1945 are interesting by the fact that the main burden of the struggle with enemy tanks lay upon the artillery. Soviet tank units played a secondary role in the fighting.

Tactically, the Soviet anti-tank, divisional and self-propelled artillery stood out in the most favorable light. The techniques for conducting fire from close range at the most vulnerable locations on the German tanks and self-propelled guns – the flank and rear – were firmly confirmed. In the process, the most combat capable German panzer army at that time – the Sixth SS Panzer Army – suffered heavy losses:

In the period of the offensive, the German command undertook the commitment of tank groups consisting of 40 to 80 armored vehicles each simultaneously on several directions, with the aim of dispersing and breaking up our means of anti-tank defense. With such actions, the adversary obtained no success, and such a tactic led him to lose 80% of his tanks and self-propelled guns, which were destroyed by our anti-tank artillery, tanks, self-propelled guns and aircraft.

As concerns the losses in equipment, according to data of the 3rd Ukrainian Front, over the 10 days of fighting, 324 German tanks and self-propelled guns, as well as 120 armored halftracks, were left burned out on the battlefield; another 332 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 97 halftracks were knocked.

According to German data, however, as of 13 March the irrecoverable losses of the Sixth SS Panzer Army amounted to 42 tanks and 1 halftrack (!). True, another 396 tanks and self-propelled guns and 228 halftracks were in the repair shop for short-term or long-term repairs. If you consider, though, that according to German documents a short-term repair could last for a month (and sometimes even longer), while no deadline at all was given for the completion of long-term repairs, then it will be clear that the German count of its armor losses is quite far from the truth. In addition, it should be considered that long-term repair was related to those vehicles that had to be evacuated from the battlefield. In addition, the German armor vehicles could switch from one category to another: initially short-term repair, then long-term, and then it might be written off as an irrecoverable loss.

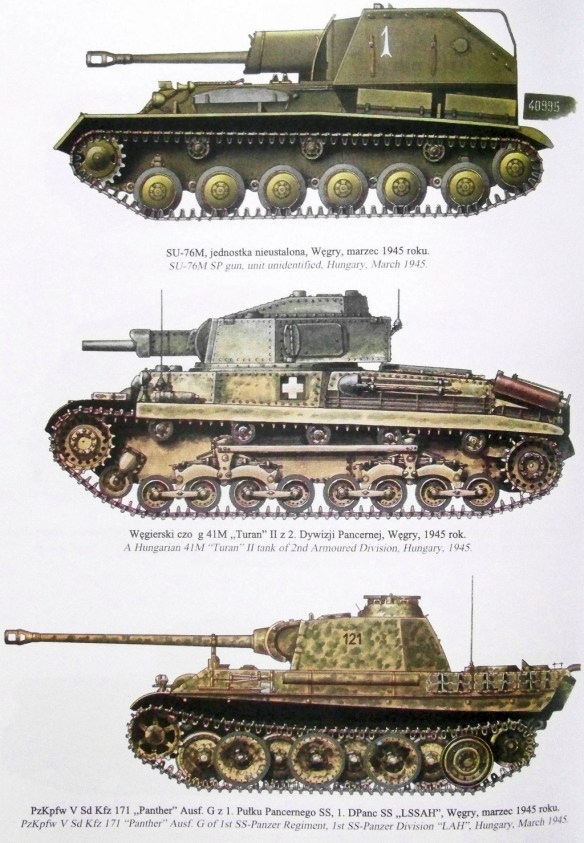

In sum, if we take the number of burned-out armor vehicles claimed by the 3rd Ukrainian Front, we won’t be far from the truth. The photos of the knocked-out or abandoned German armor in the Lake Balaton region, which were taken in the second half of March 1945 and are reproduced in this book, serve as confirmation for this. The author possesses photographs of 279 German tanks and self-propelled guns, which were marked with numbers by the Soviet trophy team, of which there are 70 Panthers, 40 Pz IV, 28 King Tigers, 3 Tiger I, 44 tank destroyers (Pz IV/70 and Hetzers), 22 assault guns, 17 Hungarian tanks and self-propelled guns, and a number of other vehicles. At the same time, the highest identification number that is visible in the photographs of the knocked out armor is 355. Considering that the photos depict 279 armor vehicles and just one halftrack, it can be assumed that the missing numbers all relate to German halftracks. Thus, one can confidently state that the irrecoverable German losses of tanks and self-propelled guns in the course of Operation Frühlingserwachen amount to no less than 250. As concerns Soviet losses, then over the 10 days of fighting they amounted to 165 tanks and self-propelled guns, of which T-34s comprised the largest number (84), followed by SU-100s (48).

On 16 March 1945, the units of the 3rd Ukrainian Front went on the offensive according to plans for the Vienna operation. The Sixth SS Panzer Army, after the heavy losses it had suffered in Operation Frühlingserwachen, was unable to offer serious resistance, and it was driven out of Hungary and into Austria literally within two weeks. Its remnants later surrendered in part to the Soviets, in part to the Americans, near Vienna in May 1945.