In fact, the US Navy was inexplicably slow off the mark to apply the principle of swept wing aerodynamics and its arch rival, the USAF, initially made all the running. This is even more surprising when it is realised that the fighter that effectively gave them command of the skies in the Korean War was actually developed from a naval jet fighter. This was the famous North American F-86 Sabre, which had its origins in the FJ-1 Fury that had been ordered by the Navy in 1944. This was a straight-winged single-engined fighter characterised by its then unique nose intake and straight-through jet configuration. The USAAF ordered a land-based version under the designation XP-86 but a courageous decision was taken to delay delivery and production for a year so that the design could be recast to incorporate a 35-degree swept wing and powered flying controls. Even so, the first XP-86 flew as early as 1 October 1947 and a few months later became the first US fighter to exceed the speed of sound in a shallow dive. The initial production version became the F-86A Sabre and by the end of 1949 two USAF fighter groups were equipped with the new fighter, which proved to have excellent handling characteristics. Subsequently several thousand were built in the United States with licence production being undertaken in Canada, Italy, Australia and Japan. The Sabre can be regarded as one of the most famous aircraft ever built.

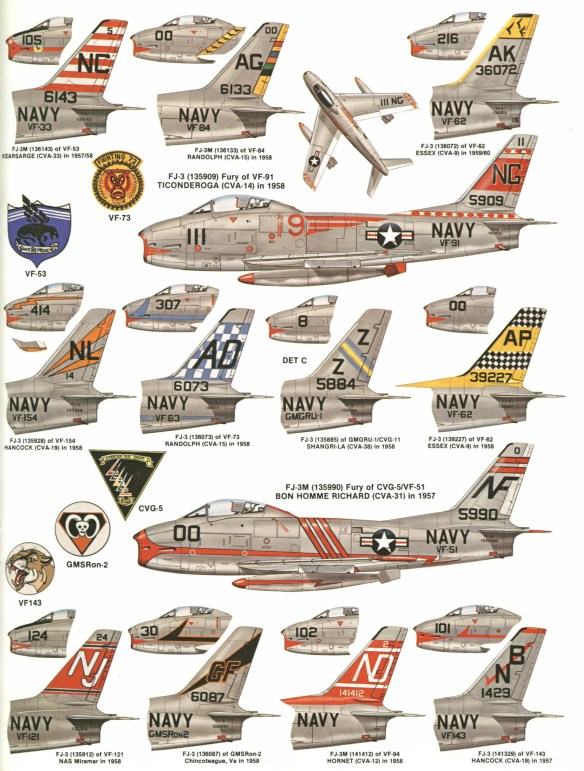

Despite its naval origins, the US Navy did not take a serious interest in the Sabre until after the outbreak of the Korean War and eventually ordered three prototypes of a naval version in March 1951. These were designated FJ-2 Fury and eventually some 200 were produced. In most respects they were standard F-86E Sabres powered by 6,000 lb thrust General Electric J47-GE-2 turbojets, which gave a maximum speed of 676 mph at sea level, an initial rate of climb of 7,250 feet/min and a combat ceiling of 41,700 feet. The only modifications for naval service were the obvious ones of an arrester hook, catapult attachment point and power folding wings, as well as a lengthened nosewheel oleo to increase the angle of attack for catapult launches. In addition the armament was changed from six 0.5 inch machine-guns to the standard US Navy fit of four 20 mm cannon. Despite these limited changes, FJ-2 Furies did not begin to reach operational units until January 1954 due to the priority accorded to Sabres for the Air Force and most were allocated to USMC squadrons. Later that year US Navy squadrons began to receive a more advanced version of the Fury under the designation FJ-3. Development of this had started in March 1952 and the main change was the installation of a much more powerful Wright J65-W-2 engine rated at 7,800 lb thrust. This necessitated an enlarged nose intake and a slightly deeper fuselage profile and production aircraft were powered by the slightly derated J65-W-4 engine. In passing it should be noted that the J65 was in fact a licence-built version of the British Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire turbojet and this was used by several other US Navy jets.

Some 538 FJ-3s were built between 1953 and August 1956 and the aircraft equipped no fewer than seventeen US Navy and four Marine squadrons. The first unit was VF-173, which received its Furies in September 1954 and was deployed aboard the USS Bennington in May 1954. An aircraft from another US Navy fighter squadron (VF-21) was the first jet to land aboard the new carrier USS Forrestal, this event occurring on 4 January 1956. In that year also missile-equipped FJ-3Ms began reaching the fleet, these being fitted to carry up to four Sidewinder air-to-air missiles. The final Fury variant was the FJ-4, which first flew in October 1954 and represented a complete redesign with the objective of increasing range and endurance. The requirement to carry 50 per cent more fuel resulted in a new fuselage outline while thinner wings and tail surfaces were also fitted. To improve handling aboard carriers, a wider track undercarriage was fitted. A total of 152 FJ-4s were produced but these were used almost exclusively by Marine squadrons, replacing the earlier FJ-2. Deliveries began in February 1955. These were intended for use in the close support role and the four underwing pylons could carry either bombs or missiles. The ultimate attack version was the FJ-4B, which did not appear until the end of 1956 but this had six weapons stations and was fitted with a Low Altitude Bombing System (LABS), which enabled the Fury to use the toss bombing technique to deliver a tactical nuclear weapons. The FJ-4B was issued to nine US Navy and three Marine attack squadrons and when production ended in May 1958 a total of 1,112 swept wing Furies had been delivered, making it one of the most significant naval fighters of the period.

To some extent the development of a naval version of the F-86 Sabre was driven by the sudden appearance of the swept wing MiG-15 over Korea and the realisation that the US Navy’s current straight-winged jets were outclassed. The same motive also led directly to a swept wing development of the existing Grumman F9F-5 Panther. In fact, Grumman had investigated the possibility of swept wing variant when the original Panther design had been proposed but although some design work was done, the decision was made to concentrate on getting the Panther into service. There were also doubts about the suitability of swept wing aircraft for carrier operations due to the problem experienced at that time with low-speed handling. However, the appearance of the Russian-built MiG swept such concerns aside and Grumman was authorised to proceed with the construction of three swept wing Panthers in December 1950. The project was given the highest priority with the result that the prototype F9F-6 Cougar flew in September 1951 and VF-32 received the first production examples in November 1952, although by the time the aircraft was ready for operational deployment the Korean War had ended.

Compared with the Panther, the most obvious change was fitting a new wing with 35 degrees of sweepback at quarter chord, as well as a similarly swept tailplane, although the vertical tail surfaces were substantially unchanged. Inevitably the stalling and approach speeds increased but to assist low-speed handling the chord of the leading edge slats and trailing edge flaps was increased, larger flaps were fitted below the centre section, and rudder controls were boosted by the addition of a yaw damper. The forward fuselage was lengthened by 2 feet and the wing centre section, which included the air intakes, was also extended forward. The lengthened fuselage allowed internal fuel capacity to be increased to allow for the fact that wingtip tanks (as on the Panther) could not be fitted. Flight testing resulted in changes, including the adoption of an all-flying tail and the introduction of spoilers to replace conventional ailerons and improve lateral control. Finally, it was found necessary to fit conspicuous wing fences to reduce a tendency for the airflow to spread spanwise and cause difficulties with lateral control. Taken together, these changes substantially improved handling to the extent that most pilots found the Cougar easier to handle in the carrier environment than its straight-winged predecessor. It should be noted that the problems that the Grumman team experienced echoed those that had affected the British Supermarine Type 510 and Hawker P.1052, and the solutions adopted were much the same.

The Cougar was powered by a 7,000 lb thrust Pratt & Whitney J48 turbojet, which had also been installed in the later Panther variants and was actually a development of the Rolls-Royce Nene of which the British equivalent was named the Tay. However, by the early 1950s new British jet fighters were being designed around axial flow engines such as the Avon and Sapphire and the only British application of the Rolls-Royce Tay was in an experimental jet-powered version of the Viscount airliner (Type 633), which flew in March 1950 but did not enter production. On the other hand the Cougar proved extremely adaptable and ultimately a total of 1,988 were built, the last being delivered as late as February 1960. Although too late to see service in the Korean War, the Cougar rapidly replaced Panthers and Banshees in some twenty US Navy squadrons, these all receiving the F9F-6 and -7 versions. In a parallel with Panther experience, the F9F-7 was powered by an American-designed Allison J33-A-16 turbojet rated at 6,350 lb thrust. However, most of these were eventually refitted with J48s and the last fifty produced were completed with the more powerful Pratt & Whitney engine.

Once the basic F9F-6 was established in production, Grumman had time to look at improving the design and this resulted in the F9F-8, which first flew on 18 January 1954. This incorporated several changes to the wing, including a thinner profile, increased wing area, and extended and cambered leading edges. Additional fuel tankage was incorporated in the extended leading edges and the fuselage tank was enlarged, increasing total capacity from 919 to 1,063 US gallons. The wing modifications resulted in a useful increase in critical Mach number and the additional fuel increased range by almost 300 miles. However, the extra weight reduced the rate of climb and service ceiling but this was offset to some extent by much improved handling and manoeuvrability. There were several sub variants of the F9F-8, including a photo reconnaissance version (F9F-8P), which flew in February 1955, and a two-seat trainer (F9F-8T), which flew in February 1956. Finally, some Cougars were modified for the tactical nuclear strike role with the fitting of LABS as in the FJ-4B Fury and these were designated F9F-9B. Although fighter versions of the Cougar were phased out of frontline service with the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets service by 1959 in favour of more advanced types, the F9F-8P was operational until 1960. The trainer version (later redesignated TF-9J) served with five training squadrons and the last of these, VT-4, did not relinquish its Cougars until 1974. In addition, many reserve units continued to fly Cougars throughout the 1960s.

Although too late to see combat, the swept wing Grumman Cougar and North American Fury provided the backbone of the US Navy’s carrier air groups in the years following the Korean War. As already related, both were developed from straight-wing, first-generation jets under the impetus of the challenge presented by the Russian-designed MiG-15. However, by the early 1950s the US Navy had other projects underway for even more advanced aircraft, although none of these would see full-scale service until the latter half of the decade. The benefits of swept wings had become apparent when allied engineers and scientists gained access to the results of German wartime experience and research, but there were other advanced aerodynamic features that the Germans had applied and a number of US designers attempted to make use of these. Foremost amongst these was the concept of the delta wing pioneered by Dr Alexander Lippisch and when the US Navy needed a fast-climbing interceptor, this configuration appeared to offer some significant advantages. During World War II, the principle of a standing Combat Air Patrol (CAP) was established with waiting interceptor fighters being directed by radar onto incoming targets. However, the new jet fighters had limited endurance so a standing airborne CAP was difficult to organise and costly in fuel consumption. Perhaps more significantly, the performance gap between fighters and jet bombers had narrowed considerably to the extent where the bomber would be difficult to catch in a pursuit scenario. From this problem evolved the concept of a Deck Launched Interceptor (DLI), which remained on short-notice standby on the carrier’s deck. Assuming an inbound missile-armed bomber flying at 550 mph at 40,000 feet was detected by radar at a range of 100 miles, a further nine or ten minutes would elapse before it was close enough to launch its missiles. If the DLI was at five minutes’ notice, this left less than four minutes for it to launch, climb to 40,000 feet and destroy its target. This implied a minimum rate of climb of around 15,000 feet/min, as well as high speed and good manoeuvrability at that altitude.

To meet this requirement the Douglas company proposed a delta-wing fighter powered by a Westinghouse J40 axial flow turbojet, which was expected to provide 7,000 lb thrust, increasing to 11,600 lb with afterburning. A development contract was awarded in June 1947 but as design work got underway the wing planform was progressively modified. Instead of a pure delta wing, the final configuration was more akin to a tailless aircraft with low aspect ratio wings having a sharply swept leading edge and rounded wingtips. The pilot sat well forward with bifurcated leading edge intakes just behind the cockpit. A tricycle undercarriage with a long nosewheel oleo for catapult launches was fitted, and the resulting high angle of attack on the ground required a small retractable tailwheel to guard against excessive pitch up at launch. The standard armament was four 20 mm cannon – a missile armament not being contemplated at this time. With the design finalised, a contract for the construction of two prototype XF4D-1 Skyrays was awarded in December 1948, although the first of these did not fly until 23 January 1951. Even then flight testing was limited due to the fact that the intended Westinghouse J40 engines were not ready and both prototypes were initially powered by Allison J35-A-17 turbojets, which were only rated at 5,000 lb thrust so that the full performance envelope could not be demonstrated.

As will be seen, the Skyray was not the only aircraft to suffer from problems with the J40 engine, which also formed the basis of several other contemporary projects. Even when production examples of the engine became available, they proved to be very unreliable with an alarming tendency to shed turbine blades in flight. Eventually the whole engine project was cancelled in 1953. Nevertheless, the availability of early J40s allowed the Skyray to demonstrate its potential, which it did in spectacular fashion on 3 October 1953 by wresting the absolute world airspeed record from Britain (set by a Supermarine Swift on 26 September 1953 with a speed of 735.7 mph). The average speed achieved by the Skyray over a 3 km course was 752.944 mph. It is interesting to note that both records were set at very low level in very high ambient temperatures where the speed of sound would be in excess of 760 mph so that Mach numbers in the region of 0.98 were attained. In fact, neither aircraft was supersonic in level flight at that time, although they could exceed Mach 1.0 in a dive, especially in colder air at high altitude where the speed of sound reduced to around 660 mph. Despite this success, the cancellation of the J40 engine programme forced the Douglas team to find a suitable alternative and this was to be the Pratt & Whitney J57-P-2. In fact, this was a much better engine, offering 9,700 lb thrust, which could be boosted to 14,800 with afterburning, and was to prove a very reliable powerplant. The later J57-P-8 offered 10,200 lb dry thrust and 16,000 lb with afterburning. Although the physical integration of the new engine with the Skyray airframe posed few difficulties, trials with the first production aircraft (first flight 5 June 1954) revealed aerodynamic problems with the air intakes, which were eventually solved by the addition of a splitter plate between the fuselage and intake, a device applied to many subsequent supersonic aircraft. However, this added further delays to the Skyray’s service debut and it was not until mid 1956 that it finally became fully operational, five years after the first prototype and almost two years after the first re-engined production aircraft had flown (although initial carrier trials were carried out by one of the J40-powered prototypes aboard the USS Coral Sea in October 1953). Nevertheless, the US Navy now possessed a remarkable interceptor. With the J57 engine, the Skyray was now just supersonic in level flight at altitude and had an initial rate of climb in excess of 18,000 feet/ min. In May 1958 a Skyray set a series of time to height records, reaching 15,000 metres (49,212 feet) in only two minutes and thirty-six seconds! The capturing of the world airspeed record was the first time that this had been achieved by a carrier-capable aircraft and the production F4D-1 was the US Navy’s first supersonic fighter, although only just so. Outside the time scale of this book, it is interesting to note that Douglas produced an advanced version of the Skyray, which was the F5D-1 Skylancer. The prototype flew in 1956 and reached speeds of Mach 1.5 at 40,000 feet, as well as possessing a limited all-weather capability, but was not ordered into production.