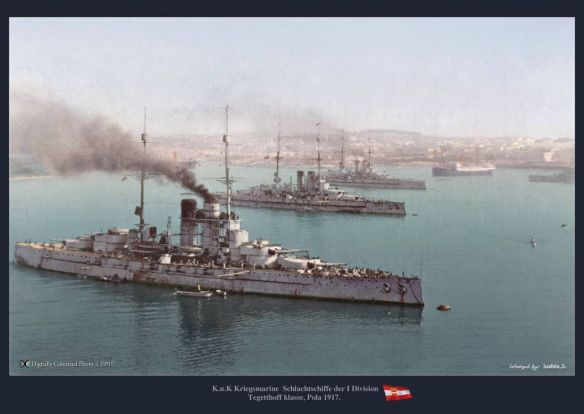

Austro-Hungarian battleships 1 Division K.u.K. Tegetthoff Class. Pola 1917.

BY Andrew South

In 1906 there was a new club in town. One that only the richest and most powerful of nations could really afford to join. Its chief asset was bigger, faster, shapelier and more powerful than all that had gone before. Membership of this ‘exclusive’ club sent the message “don’t mess with us”. As with all new ‘must-have’s’ those who couldn’t afford to join, ‘wanted-in’ all the more, so they too would be seen as a ‘Great Power’. In 1906 the must have item was the dreadnought, and the Hadsbur’s wanted in.

The Tegetthoff Dreadnought class (often referred incorrectly to as the Viribus Unitis class) was destined to be the only class of dreadnought ever to be built and completed for the Austrian-Hungarian Imperial Navy. The class would after much scheming and politicking, be comprised of four ships, the Viribus Unitis (pronounced: “var-e-buss Unit-is”), Tegetthoff(“tea-gee-toff”) , Prinz Eugen, (“Prinz U-jen”)and the Szent István (“Scent ist-van”). Three of the four ship’s were to be built in, what was until 1918, the fourth largest city in the empire, Trieste. The fourth vessel, the Szent István, was constructed in the Empire’s Croatian port of Fiume. The allocation of the two construction sites was in an effort to ensure that both parts of the Dual Monarchy, or Empire, benefited from and agreed the funds for these four ‘status’ symbols.

GROUNDWORK, SCHEMING AND POLITICS

In September 1904, the Austrian Naval League was founded and in October of the same year Vice-Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli was appointed to the posts of Commander-in-Chief of the Navy and Chief of the Naval Section of the War Ministry. These two events help set the stage for what was to be an expansion of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, in to one that was deemed worthy of a ‘great power’. Montecuccoli commenced his tenure from day one, by championing his predecessor, Admiral Hermann von Spaun’s ideas, and pushed for both an enlarged and a modernized Imperial navy.

There were a number of other factors that was to help lay the foundation for the proposed naval expansion. Between 1906 and 1908 railways had been constructed that finally cut through the Austrian alps, linking both Trieste and the Dalmatian coastline with the rest of the Habsburg Empire. In addition lower tariffs on the port of Trieste led to the expansion of the city and a growth in the Austria-Hungarian merchant navy. These changes brought the ‘need’ for new battleships that were more than just the existing coastal defence ships. Before 1900 the empire had not seen the need for sea power in support to the Austrian-Hungarian foreign policy, plus the public had little interest in a navy. But in September 1902 the situation undertook a change when Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and pro-naval expansionist, was appointed to the position of Admiral at the close of that years naval manoeuvre’s . This increased the importance of the navy in the eyes of both the general public and the two Austrian and Hungarian Parliaments. Franz Ferdinand’s interest in naval affairs had come from his belief, that a strong navy would be needed if the Empire was to successfully compete with its Italian neighbour. Ferdinand viewed Italy (an ally) as Austria-Hungary’s greatest threat within the region.

In 1882 Italy had joined the Triple Alliance with Austro-Hungary and Germany, all agreeing to fighting together against any possible mutual enemies (ie Great Britain, France or Russia). But despite the treaty Austria and Italy had a mutual rivalry they could never shed, something that had strengthened since the war in 1866, when an Austrian army defeated an Italian army several times and the Austrian fleet defeated the Italian fleet in the battle of Vis (Lissa) on July 20th 1866. Despite being ‘allies’ Italy’s navy, (the Regia Marina) remained the main regional opponent with which Austria-Hungary, often negatively, measured itself against. The gap between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian navies had existed for decades, and in the late 1880s Italy had claimed the third-largest fleet in the world, behind the French and Royal Navy. But by 1894 the Imperial German and Russian navy’s had overtaken the Italians in the world rankings. By that stage the Italians claimed 18 battleships in commission or under construction in comparison to just 6 Austro-Hungarian battleships.

With the completion of the final pair of Regina Elena class battleships, in 1903, the Italian Navy decided to construct a series of large cruisers rather than additional battleships. In addition a scandal erupted involving the Terni steel works’ armour contracts, which was to lead to a government enquiry and that in turn led to the postponement of a number of naval construction programs over the next three years. These factors meant that the Italian Navy was unable to commence any construction on another battleship until 1909, and this ‘unplanned holiday’ provided the Austro-Hungarian Navy with an opportunity to close the gap between their two fleets.

But even by 1903 the Italian lead in the naval arms appeared to be insurmountable for the Empire. Then the rules of the game changed in 1906, with the launch of HMS Dreadnought and the increased tempo of the Anglo-German naval arms race it brought. The value of the worlds existing battleships (or what history has relabeled as the pre-dreadnought) vanished all but overnight and the fleets of pre-dreadnoughts within the worlds navies were rendered obsolete. This presented the Austria-Hungarian Admiralty with an opportunity to make up for their past neglect in naval matters.

In the Spring of 1905, soon after his assumption as Chief of the Navy, Montecuccoli laid out his first proposal for a modern Austrian fleet. He envisaged a fleet comprising of 12 battleships, 4 armored cruisers, 8 scout cruisers, 18 destroyers, 36 high seas torpedo craft, and 6 submarines. The plans were ambitious, but they still lacked any ships of the size of the dreadnought type. The Slovenian politician and prominent lawyer Ivan Šusteršič presented a plan to the Reichsrat in 1905, seeking the (ambitious and unrealistic) construction of nine dreadnoughts. The Austrian Naval League also presented its own proposals for the construction of a number of the new dreadnought type. The league petitioned the Naval Section of the War Ministry in March 1909 to construct three dreadnoughts of 19,000 tonnes (18,700 long tons). They argued that the Empire needed a strong navy, in order to protect Austria-Hungary’s growing merchant navy, and in addition that Italian naval spending was twice that of the Empire.

With the completion of the final pre-dreadnought from the Radetzky class, Montecuccoli drafted his first proposal for Austrian-Hungarian’s entry into the ‘Dreadnought Club’. Making use of the newly established political support for naval expansion that he had raised in both Austria and Hungary, plus Austrian concerns of a war with Italy over the Bosnian Crisis during the previous year, Montecuccoli drafted a new plan to Emperor Franz Joseph I in January 1909. In it he called for an enlarged Austro-Hungarian Navy, now comprising of 16 (+4) battleships, 12 (0) cruisers, 24 (+6)destroyers, 72 (+36) seagoing torpedo boats, and 12 (+6) submarines. With what was fundamentally a modified version of his 1905 plan. The major new inclusion was the four additional dreadnought battleships with a displacement of 20,000 tonnes (19,684 long tons) at load. These ships would become in time, the Tegetthoff class.

The Naval Section of the War Ministry submitted its concept for the new dreadnoughts to the shipyard Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino (STT) in Trieste, during October 1908, who then hired the former “Engineering-Admiral” and now the shipyards naval architect, Siegfried Popper, to produce a design. Two months later in December 1908, the Naval Section of the War Ministry launched a competition for the design of the ships, open to all Austro-Hungarian naval architects, with the goal of securing designs in addition to those from the STT shipyard. The contest was to run for one year and the maximum displacement was to be off 20,000 tonnes.

The Italian entry to seek membership of the ‘Dreadnought Club’ with the Dante Alighieri (“Dant-ee Al-e-gare-ee” ) which had been designed by Rear Admiral Engineer Edoardo Masdea, Chief Constructor of the Regia Marina, and was based on the “All-Big-Gun” ship ideas of General Vittorio Cuniberti.

The General had proposed a battleship with all the main guns of a single calibre and positioned for broadside fire. Cuniberti has become best known to history, as the author of an article he wrote for Jane’s Fighting Ships in 1903, calling for a concept known as the “all-big-gun” fighting ship. Until that time the navies of the world-built ships which combined a mixture of large and medium calibre guns. There was constant experimentation to refine each nations new vessels calibers and layout.

The ship Cuniberti had envisaged would be a “colossus” of the seas. His main idea was that this ship would carry only one calibre of gun, the biggest available, at the time, 12 inch. This heavily armoured “Colossus” would have sufficient armour to make it impervious to all but the 12-inch (305 mm) guns of the enemy. Cuniberti’s article foresaw twelve large calibre guns, which would have an overwhelming advantage over the more usual four of the enemy ship. In addition his ship would be so fast, that she could choose her point of attack.

Cuniberti saw this ship discharging a sufficient enough broadside, all of that one large calibre, that she would overwhelm first one enemy ship, before moving on to the next, and destroying an entire enemy fleet. He proposed that the effect of a squadron of six “Colossi” would give a fleet such overwhelming power as to deter all possible opponents, (unless the other side had similar ships!). There was a cost for such a ship and Cuniberti’s contention was that this “Colossus” was available only to a “navy at the same time most potent and very rich”.

Cuniberti proposed a design based on his ideas to the Italian government, but the government declined for budgetary reasons, giving Cuniberti permission to write the article for Jane’s Fighting Ships. The article was published before the Battle of Tsushima, which only served to vindicated his ideas. There, the real damage was inflicted by the large calibre guns of the Japanese fleet.

The design work on the Italian dreadnought Dante Alighieri, (Motto “with the soul that wins every battle”(it was never to fight a battle!)), had put the Austro-Hungarian Navy in a bad position. The Italian ship was mainly a result of the leaking of Montecuccoli’s Spring 1905 memorandum, while his plans for the construction of the four new dreadnoughts still remained in their planning stages. Making the matter more complex was the collapse of Sándor Wekerle’s government in Budapest, which left the Hungarian Diet, for nearly a year, without a Prime Minister. With no government in Budapest to pass a budget, efforts to secure funding and begin the construction came to a halt.

In January 1908 the German navy magazine ‘Marine Rundschau’, carried the news that the keel of the first Italian dreadnought was about to be laid, and the news brought an Austrian-Hungarian reaction. Montecuccoli duly announced on the 20th February, during the meeting of parliament, the building of dreadnoughts of between 18,000 and 19,000 tonnes. In March, Germany was to launch her first dreadnought, the Nassau, and as a result Italy postponed the laying of the keel for her dreadnought, because Cuniberti and his chief naval engineer Edoardo Masdeo wanted to now rethink their own design. On November 5, 1908, the Navy asked the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino and Danubius shipyards to participate in the application. The main criteria of the battleships to be built were August 1909: four triple firearms, 280 mm armor and a maximum displacement of 21 000 tonnes

The design competition that had been organised by the Austrian Naval Section was to be overshadowed by events during the next six months. In January 1909 Emperor Franz Joseph had approved Montecuccoli’s plans, who then circulated it amongst the governments in Vienna and Budapest. In March 1909 Popper presented his five designs for the ‘Tegetthoff’ class. These first drafts were merely enlarged versions of the Radetzky class and had yet to include the triple turrets which would become the hallmark later of the Tegetthoff’s. In April Popper was issued with a further set of proposals, named “Variant VIII” which included the triple turrets. At the same time the Austrians asked their German ally for information on the design of their newest class. The Kaiser’s permission was received in April and the Austro-Hungarian Captain Alfred von Koudelka was dispatched to Berlin to research the technical details of the German dreadnought projects. He was personally received by Admiral von Tirpitz and allowed by the Germans to examine their latest projects, which featured both excellent armour and underwater protection. Tirpitz made an effort to explain to Koudelka the importance of torpedo protection throughout the entire design process . He explained that there needed to be at least two meters distance between the hulls outer and inner walls, as well as between the inner wall and the torpedo defence wall. Tirpitz’s knowledge was based on a series of 1: 1 scale section experiments. In addition to help reduce the impact, coal must be stored between the inner and the torpedo wall. Tirpitz stressed that the hull should be sub-divided into watertight compartments with bulkheads of strong construction. He advised that the watertight bulkheads should not be weakened with the inclusion of doors, because of the chance of them accidentally being left open, and in addition that the bulkheads should be solid with no door, pipe or wires passing through them.

Koudelka had brought with him the plans made by STT and showed them to Tirpitz, seeking his opinion. Tirpitz replied that the armament (10×305 mm guns in twin turrets) was too much for the planned 20,000-ton displacement. He proposed leaving one of the turrets off and reducing the armor thickness, and a thickening of the armoured belt. In addition, he considered the planned torpedo protection of the ships to be defective, the importance of which he specifically called to Koudelka’s attention.

On his return to Austria, Koudelka recounted Tirpitz’s input to Siegfried Popper, who simply ignored the information. In spite of the warnings, Popper insisted on his own ideas, and threatened his resignation, which unfortunately was not accepted and the Navy did not challenge his insistence, so the German experience was ignored.

The distance between the outer hull and the torpedo wall was finally only 1.7 to 2.5 meters in line with Popper’s plans. The Germans also advised the Austrian to strengthen their underwater protection, to install no watertight doors below the waterline, increase the displacement of the ships to 21,000 tons, and reduce the number of main guns from 12 to 10. All points, the Austrians were to ignore, since the basic Tegetthoff design had already been passed on 27 April 1909. In the same month Montecuccoli’s memorandum found its way into the Italian newspapers, causing hysteria among the Italian population and their politicians. The Italian Government made use of the leaked report for initiating their own dreadnought program, and allocation for the navy of the funds it would require.

Finally on the 6th June the Italian Dreadnought ‘A’ (the future Dante Alighieri) was laid down at the naval shipyard in Castellammare di Stabia, and as a result the Austrian C-in-C saw no difficulty in obtaining the required funds in the 1910 budget (due to be discussed in November 1909). Two of the Radetzky class pre-dreadnoughts had been launched by this stage, and STT needed additional contracts to retain their force of skilled workers. In August 1909 Montecuccoli suggested that maybe, while the government resolved the budgetary issues, STT and Škoda might like to start construction at their own expense (and risk). When for political reasons the dreadnought funds were refused, Montecuccoli embarked on an elaborate campaign of deception to disguise the fact that the ships were to be built without any parliamentary approval. He claimed, erroneously, that the ship building industry was financing the construction on pure speculation, and the shipyards were very uneasy with the situation. It wasn’t until Montecuccoli took a 12 million crown (£12,559,526 at 1914 or £1,377,228,920.96 at 2017 prices) crowns credit on his own responsibility that the keels of dreadnoughts ‘IV’ and ‘V’ were laid down on 24th July, (Viribus Unitis) and 24th September 1910, (Tegetthoff). In the meantime, on the 20th August 1910, Italy had launched the Dante Alighieri and had already started construction of her second dreadnought, the Giulio Cesare on the 24th June. In addition France on the 1st September 1910, laid the keel of her first dreadnought, (the Courbet) to match the Central Powers’ growing dreadnought superiority in the Mediterranean.

The finalized contracts held penalty causes and in the Szent István these included: “For each whole tenth node to which the test drive speed should be lower than 19.75 knots, a reduction of the delivery price of 20,000 crowns court will enter … also excess weight is for each ton over the präliminierte Total weight of the machine complex of 1,056 t, a discount of 800 Kr. access … the warranty period is one year… The occurrence of warlike events: Should warlike events threaten or actually occur during the construction period, the contractor undertakes to strictly obey all instructions given to accelerate the construction of the ship and the machines from the kuk Kriegsmarine. A separate agreement will be reached on the rights and obligations that ensue, but any late drafting thereof may not affect the implementation of the acceleration referred to therein. Completion date is July 30, 1914.”.

Now that the construction of the first two dreadnoughts had been committed to, Austria-Hungary had to spend around 120 million Krone (very approximately 1 kr=£1), without the approval of either the Austrian Reichsrat or the Diet of Hungary, on a deal that was to be kept secret. Montecuccoli drafted several excuses to justify the dreadnoughts construction and the need to keep their existence a secret. These included the navy’s urgent need to counter Italy’s naval build up and desire to negotiate a lower price with their builders.

In April 1910 the agreement was finally leaked to the public by the newspaper of Austria’s Social Democratic Party, the ‘Arbeiter-Zeitung’, but the plans had already been completed and construction on the first two battleships, Viribus Unitis and Tegetthoff, was about to begin.

The two Austrian dreadnoughts were already into the early stages of construction when the joint parliamentary bodies met in March 1911 to discuss the 1911 budget. In his memoirs, former Austrian Field Marshal and Chief of the General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf, (the man who, three years later, would push the Emperor to permit Serbia no leeway and push him to declare war), wrote that due to his belief in a future war with Italy, construction on the dreadnoughts should begin as soon as possible. He also worked at a plan to sell the dreadnoughts to, in his words, a “reliable ally” (which could only be Germany), should the budget crisis fail to be resolved in short order. But ultimately in 1911 the Austro-Hungarian parliament agreed to Montecuccoli’s action and even added two more ships to the plan, the future Prinz Eugen, and Szent István.

THE HABSBURG’S DREADNOUGHTS (1909-1925)

THE HABSBURG DREADNOUGHTS (1909-1925): The story of the Tegetthoff class. (Warships of world war one) Paperback – August 16, 2018

by Andrew South (Author) Since the 1970’s I have had a passion for all things Naval & in particular WW1. I find the pre-aircraft and electronic days fascinating within the context of the war at sea. Now with the wonders of the net & the knowledge I have gathered I thought it time to try & give something back & to share my passion. I’m an ‘naval enthusiast’ but so many of us are. I run a small group on Facebook & have had a number of articles published in various on line magazines and forums. I’ve written articles on von Spee’s campaign, dreadnought profiles and campaigns. After 40+ the passion is still with me.