For our story one of the most important aspects of the war with Iugurtha was the extraordinary rise of Marius. Metellus had failed to bring the war to a swift conclusion, and seemed to be unable to physically capture Iugurtha. He therefore resorted to bribery, coupled with a policy of reducing the urban communities in Numidia, so as to deprive the king logistically. Marius was to employ the same strategy against Iugurtha, so we should be wary of any criticism of Metellus’ conduct in this war. For instance, Sallust records the total massacre of the Roman garrison at Vaga (Beja, Tunisia), all bar its commander Titus Turpilius Silanus, after the town’s betrayal to Iugurtha. When Metellus retook Vaga he promptly put its inhabitants to the sword, and Turpilius himself was arrested and put to death. Sallust claims Turpilius was civis ex Latio, a Roman citizen of Latin origin, and thus could not be executed without a proper trial. Yet it seems that Turpilius was only a first-generation Roman citizen and Metellus conveniently ignored his status and treated him as a non-Roman, and a treacherous one at that. Marius was to use this episode against Metellus in his campaign for the consulship.

Sallust describes how Metellus, when Marius asked permission to return to Rome to seek a consulship, exhibited the characteristic haughty arrogance of the proud, traditional, Roman nobility. Sallust, who, after all, had been a partisan of Caesar before turning his hand to penmanship, suggests that Metellus was absolutely mortified that a man of Marius’ background and social standing could even think of such a thing. Whatever his exact view of the matter, he flatly denied Marius’ request. Sallust continues the story:

When Marius kept on renewing his petition, he [Metellus] is alleged to have told him not to be in such a hurry to be off. ‘It will be time enough’, he added, ‘for you to stand for the consulship in the same year as my son.’

The patrician general’s response was certainly spiteful, as his son was a lad only in his early twenties and currently serving on his father’s staff. In other words, Marius could stand when he would be about 70 years of age. Marius could hardly have taken the jab with equanimity. Realising he could expect no support from his patronus, Marius started to look elsewhere. To this end he exploited the prevailing political atmosphere in Rome, thereupon making contacts of his own, particularly among the equestrians engaged in business in Africa, and building up his own reputation by claiming that he could bring Iugurtha to bay and end the war. Although elected on the equestrian and popular vote, Marius is best seen as an opportunist and not as a popularis. He was simply exploiting popular feeling with regards to the apparent lack of swift action against Iugurtha – the war had dragged on and the expected Roman victory was not forthcoming – and thus cannot be regarded as ‘anti-senatorial’. For four years Iugurtha had defied the might of Rome and many leading senators were believed to have accepted his bribes, and even some of the generals who had conducted the first campaigns against him were suspected of treason. In any event, they had been incompetent.

None the less Metellus’ partisans in the Senate did not designate Numidia as a consular province, thus ensuring his continuing command there as a proconsul. It was a reasonable step on the Senate’s part; the plodding but honest Metellus had done much better than his incompetent predecessors, even if his progress was slower than the people had hoped for, and he was familiar with the enemy and the army, an army hardened to campaigning in the hot wastes of Numidia. All in all he was the best choice to finish off the war and restore some of the old senatorial lustre. But it was not to be.

A tribune, Titus Manlius Mancinus, went before the people and called upon them to decide who was to take charge of the war in Numidia. And so a plebiscite was passed and the new consul Marius duly received what he wanted: the African command. There was no clear precedent for this, although it is extremely difficult to argue that his appointment was unconstitutional. In 205 BC, for example, Publius Cornelius Scipio was on the point of invading Africa when the Senate hesitated on giving him the green light. Livy records that Scipio was quite prepared to go to the people if the Senate did not give him Africa as his province.

Despite being bitter, Metellus accepted the change in command – in 88 BC Sulla would not – and on his return to Rome he acquired the cognomen Numidicus for his endeavours against Iugurtha. As a matter of fact, Marius did not bring with him any new ideas on how to conduct or even win the war, but he did at least realise that to combat Iugurtha’s guerrilla activities he would need more troops on the ground. Rome, however, was suffering a longstanding manpower shortage. To this end, therefore, Marius took the decision to invite the capite censi to serve in the legions and, in the doom-laden words of Plutarch, ‘contrary to law and custom he enrolled in his army poor men with no property qualifications’. Volunteers flocked to join the legions and the Senate raised no protest. The fundamental nature of the Roman army was changed, transforming it from the traditional citizen-militia composed of a cross-section of the propertied classes into a semi-professional force recruited from the poorest elements of society. From now on legionaries saw the army as a career and a means of escaping poverty, rather than a duty that came as an interruption to normal life. Marius thus created, without realising it, a type of client army, bound to its general as its patronus.

Most of the men recruited by Marius undoubtedly were, or had been, members of the rural population, and an ex-peasant’s idea of riches was his own smallholding. At the conclusion of the African campaign they would look to their wonder-general for rewards in the shape of plots of land. There is no evidence that Marius actually promised his proletariat recruits land when he enlisted them, but as consul in 103 BC he set about providing it. So, while he was training his new army for the approaching showdown with the Cimbri and Teutones, he proposed an agrarian bill seeking land in Africa for the veterans of the war with Iugurtha.

His legislation would be pushed through by the unscrupulous and brilliant tribune Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, a demagogue who frequently resorted to mob violence, and even – it was rumoured – assassination. We can, of course, argue that from now on the legions turned to their generals and not to the Senate for recompense, a case in point being when Sulla got his troops to march on Rome in 88 BC. However, such a view is far too pessimistic as not all soldiers would follow their general come what may. They would fight loyally in the defence of Rome when it was under threat, and were bound by oath to follow their appointed commanders, but they had no commitment to a political system that did little for them.

While helping the veterans was Marius’ goal, it ought to have been a goal of the Senate too. Traditionally, the Senate had made no provision for discharged soldiers, letting them drift back home after their service, often to sink into poverty. But periods of service had lengthened, and it could not be ruled out that soldiers might be mobilised for years on end. Moreover, wars of conquest took armies far afield, and being uprooted in this way certainly hampered their chances of being reabsorbed into civilian society. Marius fought to see that this would not happen to the veterans of his campaigns. But ultimately it was the Senate that shirked this duty. It failed to recognise the new semi-professional army for what it was: an organisation with interests and concerns.

It is probably true that throughout Rome’s history soldiers exhibited more loyalty towards a charismatic and competent commander. Therefore what we actually witness with Marius is not a change in the attitude of the soldiers but a change in the attitude of the generals. Judge for yourself. In 202 BC after Zama, if he had held revolutionary ideas, Scipio could have easily marched on Rome at the head of his victorious army. If we return to Sulla and his march on Rome, his officers were so appalled at his plan that all except one resigned on the spot, while his soldiers, though eagerly anticipating a lucrative campaign out east, followed him only after he had convinced them that he had right on his side. When envoys met Sulla on the road to Rome and asked him why he was marching on his native country, according to Appian he replied, ‘To free her from tyrants’. As for Marius, well, it probably never even crossed his mind at the time that Sulla would do the unthinkable. After all, a Roman army was not the private militia of the general who commanded it, but the embodiment of the Republic at war.

But let us return to our war in Africa with which we started this particular section. On assuming command there Marius soon found that it was not as easy to end the conflict as he had claimed back in Rome. Events now took an ugly turn with Marius adopting a deliberate policy of plunder and terrorism, torching fields, villages and towns and butchering the locals. Moreover, he came very close to losing the war in a major battle not far from the river Muluccha (now the Moulouya, which forms the western boundary of Algeria), and Sallust hints that it was Marius’ quaestor, Sulla, who saved the day. We can be fairly certain that Sulla wrote this up in his commentarii. They are lost, but Sallust read them and made use of them in writing his account of the war. In the end Sulla befriended Bocchus, the king of the Moors and father-in-law of Iugurtha, and what follows was Sulla’s dramatic desert crossing, which culminated in Iugurtha’s betrayal and capture. This bit of family treachery thus terminated a war full of betrayals, skirmishes and sieges. Sulla had the incident engraved on his signet-ring, provoking Marius’ jealousy. Nevertheless, Marius was the hero of the hour. On 1 January 104 BC he triumphed on the same day he entered his second consulship.

The war with Iugurtha had been a rather pointless, dirty affair. The king was publicly executed, but the Senate did not annexe Numidia, giving instead the western half of the kingdom to Bocchus as the reward for his treachery, and the eastern half to Gauda, Iugurtha’s weak-minded half-brother. Yet it had made Marius’ reputation and begun Sulla’s career. More than that, it saw Marius and Sulla fall out over who was responsible for the successful conclusion to the war, a quarrel that was to cast a long sanguinary shadow on Rome.

War with the Northern Tribes

While Rome had been busy chasing Iugurtha, the Cimbri and Teutones, who were most probably Germanic peoples originally from what is now Jutland, moved south and inflicted a series of spectacular defeats upon the Roman armies. They now became Marius’ next concern. Rome had always been obsessed with tribal invasions, more so in 113 BC after the consul Cnaeus Papirius Carbo was routed by the Cimbri at Noreia (Neumarkt, near Ljubljana). The Senate had dispatched Carbo to keep them out of Italy. These Germanic tribes knew something of Roman power even if they were strangers to Rome, and they agreed to pull back from the peninsula. Carbo unwisely attacked them anyway, in the hope of an easy victory over the northerners. It did not turn out that way. Iulius Obsequens, diligently recording his prodigies for that year, recounts that the ‘Cimbri and Teutones crossed the Alps and made an awful slaughter of the Romans and their allies’.

Following Carbo’s defeat another tribe, the Celtic Tigurini (one of the tribal groupings of the Helvetii), joined themselves to the Cimbri-Teutonic alliance and ventured into Gaul with them. In 109 BC the three tribes circled back from their jaunt in Gaul. Near the frontier of Gallia Transalpina, the new Roman province, they came up against an army led by the consul Marcus Iunius Silanus. Doubting the outcome of a battle they offered to serve Rome in return for land. The Senate declined the offer, and the Tigurini then cut to pieces Silanus’ army but, as with the case of Carbo four years earlier, the Celts did not follow up their advantage. The Cimbri and Teutones continued west through Gaul, while the Tigurini broke off to raid Gallia Transalpina.

In 107 BC Marius’ colleague in the consulship, Lucius Cassius Longinus, advanced to recover the situation; he followed the Tigurini toward the Iberian frontier where he was defeated and killed in an ambush. The survivors were permitted to withdraw after passing under the yoke. This was a complete and utter humiliation as the yoke was made of two spears fixed upright, with a third fastened horizontally between them at such a height that the defeated soldiers filing under it were obliged to stoop in token of submission. It must have been doubly galling that the Tigurini had chosen this gesture since it was an ancient Italian custom.

Although Rome’s fortunes recovered somewhat in 106 BC the worst was still to come, for the following year was to witness the rout and destruction of two consular armies under Quintus Servilius Caepio (cos. 106 BC), now proconsul after the expiration of his consulship, and Cnaeus Mallius Maximus, one of the current consuls, at Arausio (Orange) in Gallia Transalpina. With allegedly 80,000 casualties, this was the biggest disaster to befall Roman arms since Cannae, and bickering between the two commanders was said to have been a major contributory factor here. Instead of turning east to cross the Alps, the Cimbri and Teutones moved south into Iberia and remained there for the next three years. Italy had been spared what would no doubt have been a major invasion akin to that mounted by the Gauls in 390 BC when they briefly occupied and sacked Rome itself, all save the Capitol.

In the autumn of 105 BC a pro-Marian lobby secured for Marius a second consulship, which broke all the constitutional rules since he was not even in Rome for the election but still in Africa. Yet it does appear that Marius had the backing of the Senate as Gallia Transalpina was given to him as his consular province. Fifty years later Cicero would pose the following rhetorical question in the Senate:

Who had more personal enemies than Caius Marius? Lucius Crassus and Marcus Scaurus dislike him, all the Metelli hated him. Yet so far from voting against the grant of the province of Gallia Transalpina to their enemy, these men supported the extraordinary command of that province to him so that he might command in the war against the Gauls [i.e. Cimbri and Teutones].

Marius was to be elected consul a further four times (103–100 BC, cos. III–VI), thus giving him six consulships to date. Actually these other consulships were more like generalships. There are other examples of Roman generals retaining command of an army during a period of tumult, Quintus Fabius Maximus Cunctator during the initial years of the war with Hannibal, for instance. The vital difference, however, lies in the fact that when the year of their consulship ended these commanders were given proconsular rank. There was no precedent for Marius’ string of back-to-back consulships, an offence to the idea of limited tenure of office.

The last four consulships can be seen as a popular measure, the people asserting that Marius was the man they wanted in command and that he should remain so for as long as they desired. Naturally Marius neatly exploited popular politics to achieve this unprecedented career because he could have had his command continued after his second consulship as a proconsul. But that meant he would only remain in command at the whim of the Senate. What is more, as was glaringly illustrated by Caepio, a nobilis, and Mallius, a novus homo, the working relationship between proconsul and consul could be fraught with danger. As a consul, Marius was firmly in charge and thus unassailable. As a matter of fact, apart from the rout of the army of his consular colleague Catulus early in the campaign, Marius was extremely successful, defeating the Teutones and their Celtic allies, the Ambrones, at Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence) in 102 BC and, with Catulus, whose powers had been extended as proconsul, the Cimbri one year later at Vercellae (Vercelli) on the dusty plains of northern Italy.

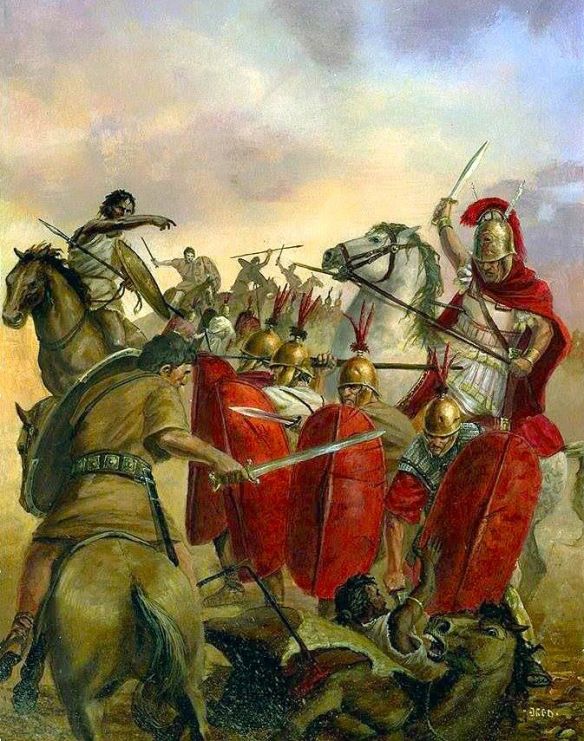

The day was an extremely hot one, it being shortly after the summer solstice, and the adroit Marius had his soldiers advance through the dust and haze. To the consternation of the Cimbri, the Romans suddenly charged upon them from the east, with their helmets seeming to be ablaze from the shining of the sun’s rays. In a ferocious struggle the Cimbri were cut to pieces, and it is reported that no fewer than 120,000 of their warriors were killed and 60,000 were captured. The war leader of the Cimbri heroically fell in this battle, fighting furiously and slaying many of his opponents.

Although he consented to celebrate a joint triumph with Catulus, Marius claimed the whole credit for the victory at Vercellae. Likewise, in popular thinking all the credit went to Marius. Catulus and Sulla, on the other hand, gave very different accounts of the battle in their memoirs. The patrician Sulla, who had joined Marius and Catulus for the northern war, naturally took the latter’s side. This was not only out of a personal dislike of Marius but also because of a natural bias toward the senatorial aristocracy, whose dangerous and bloody champion he would be.

With six consulships and two triumphs, Marius had created an extraordinary precedent. He was now a man above the system, a forerunner of Pompey and Caesar. However, at the time Marius’ unconstitutional position did have a certain amount of logic to it as he was no revolutionary and the system had worked to his advantage. The other extraordinary aspect was the temporary nature of Marius’ influence.

Political Wilderness

There is an old Latin expression gladius cedet togae, ‘the sword gives way to the toga’. If a man would be great, he must be great at home too. After his defeat of the northern tribes, Marius was hailed by the people as the third founder of Rome, a worthy successor to Romulus himself and Camillus – the old saviour from the war with Brennos the Gaul, the sacker of Rome. However, the year 100 BC, the year of his sixth and penultimate consulship, saw the great general fail disastrously as a politician. Marius would desert the tribune who had aided him, Saturninus, and stand by as an angry mob lynched him and his supporters.

The firebrand Saturninus had been re-elected as one of the tribunes for the coming year, proposing yet more radical bills, but the Senate, who saw the spectre of tribunician government raise its ugly head again, called on Marius to protect the state. Having restored public order under the terms of a senatus consultum ultimum, both literally and efficaciously ‘the ultimate decree of the Senate’, the veteran general subsequently saw his popular support slip away. The nineties BC were to be a decade of political infighting of the most extreme sort, and one of its first victims, according to Plutarch, was Marius. Yet his actions in 100 BC can be seen as a bungling attempt to announce his arrival to the nobility of Rome. Of interest here are Sallust’s remarks concerning the monopoly of the nobilitas on the consulship:

For at that time, although citizens of low birth had access to other magistracies, the consulship was still reserved by custom for the nobilitas, who contrived to pass it from one to another of their number. A novus homo, however distinguished he might be or however admirable his achievements, was invariably considered unworthy of that honour, almost as if he were unclean.

Sadly for Marius, to the nobilitas he would always be, despite his unprecedented six consulships and two triumphs, a novus homo. Despised by the inner élite and shunned by the equestrians and the people, Marius was now cast into the political wilderness. In early 98 BC Metellus Numidicus was recalled from exile – Saturninus had orchestrated this for Marius two years previously – and Marius, having tried to delay the return of his one-time patronus, admitted defeat and scuttled off to Asia ‘ostensibly to make sacrifices, which he promised to the Mother of the Gods’. The following year he did not stand, as was expected, for the censorship, a clear sign that he was not in the political spotlight.

Marius wanted to beat the nobilitas at their own political game, substituting self-made support for their inherited connections. Showing little flair for politics, it did not occur to him – as it would have done to Sulla and Caesar – that the rules of the game could not be changed. Though connected to the equestrians by birth and interests, and favouring the welfare of soldiers (including Italians, whom he truly valued as allies), he had no positive policies or solutions for the social problems of the day. As an individual he was superstitious and overwhelmingly ambitious, but, because he failed to force the aristocracy to accept him, despite his great military success, he suffered from an inferiority complex that may help explain his jealousy and, later, his vindictive cruelty. Yet he marks an important stage in the decline of the Republic: creating a client army, which Sulla would teach his old commander how to use, he was the first to show the possibilities of an alliance between a war leader, demagogues and a noble faction. His noble opponents, on the other hand, in their die-hard attitude both to him and later Sulla, revealed their lack of political principle and loss of power and cohesion.