Morocco and Songhai

The new Sultan of Morocco reflected carefully on the lessons of the battle of Alcazarquivir. His councillors were still confident in the superiority of their traditional weapons and tactics, but he had been impressed by the effectiveness of the Christian infantry. Al-Mansur imagined how the European weapons could be employed in the lightly populated centre of the continent, where the Songhai state had been recently shaken by civil war. Moreover, Moroccan trade with Songhai was being undermined by European merchants on the coast. Ships could carry so much merchandise that the Christians could undercut the prices of Islamic merchants, who had to pack their wares across the Sahara; and in the case of weapons, the Muslims would not sell them to their enemies at all.

Al-Mansur’s informants led him to believe that Songhai would not be able to respond effectively to a well-planned invasion. In late 1590, a dozen years after becoming sultan, he announced to his council that he was sending an army of 3,000-4,000 troops and thousands of pack animals and their handlers on a four-month march across 1,000 miles of desert to the Songhai capital at Timbuktu. His commander was Judar Pasha, a European-born slave and eunuch; the goal was to acquire access to the gold mines and salt, so that he could pay for the European commodities his subjects desired—this had become increasingly difficult now that Portugal’s Brazilian plantations were selling sugar cheaper than his subjects could. His force was outnumbered, but it included Turkish mercenaries and Christian bodyguards, matchlocks and cannon. The language of command was Spanish, a reflection of the importance of Iberian mercenaries in the campaign.

The Songhai Empire had been important since the early 1400s, stretching along the Niger River from the cataracts near the sea north and west for a thousand miles to distant gold fields. Its wealth came from trade, selling gold, ivory, salt and human beings across the desert to Morocco and to the Mediterranean coast. Fervently Islamic in faith, its orientation was northward. To the south lay forests, disease and paganism; it was much safer for Songhai warriors to stay in the drier but healthy regions of the Upper Niger River Valley, where the pasture land was more extensive than it is today.

The Songhai rulers were generally, but not consistently, tolerant toward the pagan practices of the southern people; as long as those peoples were divided, they were no danger, but could be exploited easily and cheaply. One ruler, Askia Muhammed I (reigned 1493-1528) had made the pilgrimage to Mecca with 500 cavalry and 1,000 infantry, establishing Songhai’s reputation for being fabulously exotic and rich. This legendary wealth had attracted al-Mansur’s attention, first for gold, then for salt—the exchange was often equal weight of one for the other.

Most of all, the sultan saw that the Songhai state was weak. Dynastic quarrels followed the death of each king; brutal efforts at imposing Islamic customs were resented both by desert nomads and farmers of the bush, all of whom believed in magic and who carefully treasured memories of past outrages. Vassal chiefs knew that their predecessors had been slain, their sons gelded and their daughters sold into slavery; and merchants resented the taxes. The royal processions were splendid and the king’s army made a brave display, but Moroccan merchants could see that the Songhai Empire was a case of the least weak ruling the weaker.

The harem system had always encouraged jealousy and fear, and when the last great sultan died in 1582, the multiplication of potential heirs had reached its logical (and disastrous) outcome—civil war.

The Invasion

In late 1590 al-Mansur’s hold on Morocco was at last secure. He had warded off European and Ottoman challenges, then expanded his kingdom into the interior, seizing some of the valuable salt mines that were central to Saharan trade. Overseas trade with Ireland, England and even Italy was prospering, and his enemies were involved in desperate wars on distant frontiers. It was an opportunity to break free of his financial troubles, those caused by the need to pay his mercenaries, by seizing the salt and gold of the African interior. Of course, his councillors were all against the expedition—it was a long journey over one of the more formidable deserts in the world, with almost no pastures and only a handful of water holes—and those were capable of supporting only small parties. He rejected this advice, heaping scorn on their caution and pointing out the advantages that gunpowder weapons and good cavalry had over men armed only with spears and bows. The numbers had to be small, he agreed, in order to cross the desert successfully, but if the troops were good, they could prevail. Conducting a siege without great cannons would be difficult, but the enemy, not knowing what they were up against, would probably come out to fight rather than watch their country ravaged.

The losses on the march must have been appalling, so it would have been wise for the Songhai king to have marched out to meet the Morrocans before they had recovered from their desert ordeal, but he did not; even his orders to fill in the wells had apparently not reached the nomad Tuareg chiefs—or they had disobeyed. Had that elemental step been taken, the Moroccan army might had died in the desert. However, the Tuaregs were Berbers; though they had little love for Arabs, they were always reluctant to take orders from anyone.

Fortunately for the Moroccans, the Songhai had not read Kenneth Chase’s analysis in Firearms of the difficulties that armies face in a desert. The demands for water, food and fodder were so great that infantry usually had to turn back after two days, cavalry after only one. Had the army been supplied with camels, it would have done better, but it appears that the Moroccans were counting on using their horses in battle. The Moroccans must have been very relieved not to have to fight for each watering place along the march, but they probably did not worry about poison—nomads were not suicidal.

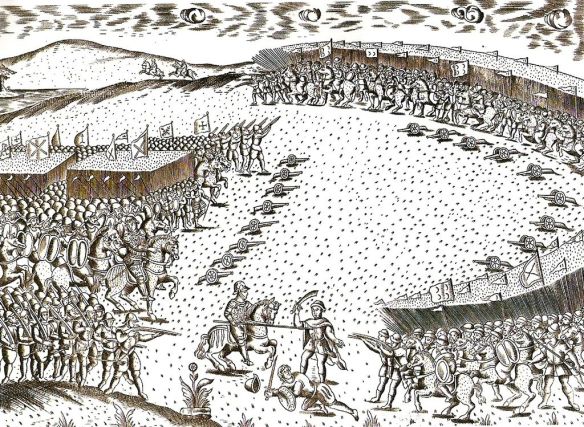

Judar Pasha’s army met the Songhai host in March 1591 in the short and violent battle of Tondibi. The mercenaries had been greatly outnumbered, but their enemies lacked the will to fight. The Songhai king drove a herd of cattle at the northerners, but volleys of infantry weapons and cannon frightened the cattle, causing them to charge back through the king’s forces, after which there was little organised resistance. Judar Pasha allowed his men to sack the cities and towns, after which he reestablished order and made himself governor, ruling from Timbuktu.

The victors were disappointed to discover that the fabled cities were collections of mud buildings, and that the gold had been taken away or hidden; worse, the gold fields were still far away, deep in Black Africa to the west. In Gao, the first city captured, the invaders found a Portuguese cannon that the Songhai warriors had not known how to use, a crucifix and a statue of the Virgin Mary. It was a fitting symbolism of Songhai military backwardness.

However, the Songhai king had survived the battle. From a safe distance he tried to pay the invaders to leave, but they refused—the gold he offered made them more eager to stay, not less. Nevertheless, the mercenaries saw little reason in holding onto their conquest, True, Timbuktu had an impressive mosque, learned scholars and some evidence of wealth, but the mercenaries had no use for places of worship or books, and they were forbidden to loot. Their numbers had been quickly reduced by illness, and the Songhai ruler continued to resist from his southern strongholds. Reinforcements were slow to arrive, and of the few sent, most were killed by Tuareg nomads. Meanwhile, chaos reigned—the king was removed by a brother, the peoples subject to the Songahi rose in revolt, and the mercenaries began to loot, rape and murder.

Judar Pasha’s discouraging report on local conditions resulted in his assignment to a much lesser post, governor of Gao. His successor was Mahmud ibn-Zarqun, a eunuch, the son of a Christian. He stripped the houses of doors and doorposts to build two ships, then set off downstream to eliminate the last Songhai forces. A stroke of luck then came his way—civil war broke out among the Songhai. The new king had ordered his brothers castrated, whereupon they had joined the Moroccan invader. This allowed Mahmud to easily scatter the remnants of the Songhai army, after which he invited the king to a conference and murdered him.

That ended resistance in the north, but desperate Songhai in the south turned to one of the late king’s brothers, Askia Nuh, who withdrew into the bush country, even into the coastal forest, where he proved himself a gifted guerilla commander. Aksia Nuh established bases in the swampy south and the rugged north where cannons and horses could not be used; and where malaria weakened the invading troops. Because the mercenaries’ atrocities had by now appalled everyone, Askia Nuh was able to make common cause with ancient Songhai adversaries, while Mahmud found it impossible to exploit their many ancient animosities; as a result, Moroccan efforts to reach the gold fields failed. Meanwhile, the collapse of the Songhai had tempted every brigand in the desert to attack the caravans, so that trade with Morocco became more dangerous. Mahmud requested reinforcements, which arrived in 1593.

Victorious. Now What?

The decisive moment in the campaign may have been Mahmud sending one of his captains with 300 musketeers back to Timbuktu to protect it against raiders. The officer apologised to local leaders for past misdeeds and promised to keep his men in barracks after dark. The policy worked—open resistance ended, trade revived and exiles returned. He then led his men north against the desert raiders and, with local help, destroyed the worst of the bandits. More reinforcements allowed him to crush a dangerous insurrection in an outlying city whose inhabitants had more passion than political acumen.

This was not a policy that pleased Mahmud ibn-Zarqun, whose own efforts to pacify the south had failed. Wanting to take revenge on his enemies, not placate them, he began to massacre Timbuktu’s leading families. Many who were not slain were loaded with chains and driven across the Sahara to Morocco. When news of this reached the Moroccan king, he ordered Mahmud removed from command. Mahmud, however, had already been killed in a fight against black pagans before his replacement arrived in 1595. Askia Nuh received Mahmud’s head with satisfaction, presumably pleased by the proof that bows and arrows could defeat firearms. But that had no immediate effect on the war; Nuh retreated to his stronghold at Dendi, while a brother, Sulaiman, was put on the throne in Timbuktu as a puppet of the occupation army.

Clearly, the distant Moroccan sultan had misjudged the situation, and he was to continue to do so. This was easily done, perhaps inevitably, considering the inadequacy of information available to him. His effort to divide duties among his commanders provoked a civil war until finally Judar Pasha suggested that the army decide which of them should rule. After Judar Pasha’s election, he poisoned his rival and then made all the appropriate gestures of loyalty and subordination to the sultan. In 1599 Judar Pasha returned home, rich with gold, slaves and exotic wares, ready to enjoy life in every respect except the founding of a dynasty.

The new Arma state was ruled by the army. Some soldiers had been Christian prisoners-of-war, others had been simple mercenaries; there were also Moors whose ancestors had fled Spain after the Reconquista, and Berber tribesmen. Most married local women, and when some tried to restrict alliances to their own races, reality struck home: where would they get women? That was the origin of a mixed race elite who eventually came to speak the language of their mothers and subjects. Since the army controlled the state, the reigns of the distant Moroccan sultans, which were often short anyway, made no difference. Civil war and rebellions prevented the Arma from becoming a powerful empire, but they had no dangerous rivals to threaten their existence.

Not even the weapons that Europeans supplied to coastal peoples threatened the northerners’ vast state. As Chase noted in Firearms, a Global History, the savannah south of the Sahara was ideal cavalry country except that its diseases were deadly to horses—more so even than to Europeans, it seems, who could at least go indoors to escape the tsetse fly. And without cavalry to force infantry into tight formations, firearms were less than fully effective. The obvious strategy for Europeans and Arma alike was to recruit light infantry from the weaker tribes, relying on them to do most of the fighting, while the heavy troops guarded the baggage and artillery.

Edward Bovill notes in The Golden Trade of the Moors that by 1660 the Arma were so weak that Timbuktu had fallen to pagan enemies. Arising from the chaos was a black military force, the Bokhari, who became important in Moroccan affairs. They, like the white mercenaries, had no local connections and were, therefore, preferred as bodyguards to Berbers or Arabs. As for the politics of the Arma lands, it was complicated beyond any hope of summarising or reading with enjoyment or edification.

Slavery Supports the State

Al-Mansur had profited immediately from his conquests, but over the long term his invasion disrupted trade and pilgrimages, thus making his gains transitory and his losses heavy. His successors were not tempted to become involved in the politics of the interior, except to buy slaves who could be employed as bodyguards and elite troops. Trained in western methods and having no stake in local politics, their loyalty to their employers could be trusted; many were eunuchs, which limited their vices to those which disturbed the public least.

Although the Moroccan sultan had expected that conquering the Songhai kingdom would increase the slave trade across the western Sahara, it shifted to the coast, where tribes hostile to the new Muslim state were now selling prisoners-of-war to Europeans.

The practice of slave-raiding tore central Africa apart for many generations to come, but it mattered little to Moroccan sultans and their supporters how many villages were destroyed and how many perished during the long march north. Everyone was in the business of procuring and selling slaves.

Kanem-Bornu

This state lay to the west of Lake Chad, across the eastern caravan trail leading from the Niger River valley to Tripoli. Most of the inhabitants were farmers, but many were herders—an arrangement that worked to mutual satisfaction throughout much of the African interior until the Darfur crisis of 2003 revealed that the complicated mixture of races and religions had been placed under intolerable pressure by population growth and the encroachment of the desert on arable lands. This was not new, however—the conflict between nomad and farmer was a part of African history from time immemorial, most recently contributing to the 1984 genocide in Rwanda. Centuries before the Darfur crisis the danger of raids from the desert required farmers and artisans to live in walled towns, the fortifications made of unimposing but effective mud bricks.

Bornu had been just beyond the reach of the Songhai armies. Its horsemen collected slaves from the savannahs and jungles to the south, some prisoners being ransomed to their families and more kept for local use (some as soldiers). Everyone owned two or three slaves, often as concubines, some as eunuchs; one king acquired so much gold that he could make golden chains for his dogs. Since it was illegal to enslave Muslims, most prisoners were pagans. The best captives, mostly women and children, had long been herded north to the international market operated by Arabs, and to the west, to the kingdom of Songhai. Eastward from Bornu the road led to the savannah of Darfur, where it split into the ‘forty day road’ across the desert to Upper Egypt and the road to Sudan and the Indian Ocean. The horsemen who made the raids believed that they had no choice in the matter—they were always desperate for more mounts, and they could buy them only from Arabs who wanted slaves.

In contrast, neighbouring Arabs tended to ride camels because the tsetse fly multiplied during the rainy season, making horse raising impossible, and transporting fodder was expensive. The Bornu warriors, however, knew that horses were better than camels for war in the grasslands to the south. They used camels, but only reluctantly.

The most important warrior-king, Idris Alooma (reigned 1571-1603), conquered all the surrounding savannah with mercenary warriors, employing exceptional brutality. Once having pacified his state, however, he encouraged commerce, culture and education; he crushed banditry, required his subjects to live by Islamic law, and built mosques through the country. The high point of his reign was his impressive visit to Mecca via Tripoli and Egypt. In the course of his travels, he became aware of firearms. Purchasing some, he had Ottoman mercenaries train his palace guard in their use. In 1636 one of his successors obtained fifteen young Christians armed with muskets. These proved so effective that he soon acquired more. Details, alas, are totally lacking.

Similarly, we know little about the settlements the rulers established along the pilgrimage route toward Mecca. The journey took pilgrims through some of the most inhospitable regions on earth, so it made sense to have places where they could obtain food and water and could rest. This also served as a route for slaves, but only for small numbers. Therefore, the slave traders seems to have concentrated on specialised classes of humans—eunuchs, dwarfs, concubines, and artisans. Since runaways stood little chance of escape, care had to be taken only to prevent suicides among slaves driven almost insane by heat and exhaustion.