There are, nevertheless, several good reasons to reject the inferiority of British design out of hand. It is essentially an explanation of how France and Spain won the naval wars – which is not what we need to explain. In the century from 1714 more than half of all French warships (ships of the line and frigates) ended their careers sunk or captured, and the proportion rose steadily. In just over twenty years of warfare from 1793 to 1815, the French built 133 ships of the line and 127 frigates; and lost 112 and 126 respectively to enemy action or stress of weather. On average they lost a ship a month for twenty years. At first sight this does not suggest superior design. Moreover the comparison between ‘good’ French and ‘bad’ British design rests on the naive assumption that the two were directly comparable, that British and French designers were building the same size and types of ship, to fulfil the same functions – in other words that the strategic situations of the two countries were the same. This in fact is what many naval historians do assume: that the Bourbon powers, and subsequently Revolutionary and Imperial France, built their navies, and had to build their navies, to mount a frontal challenge to Britain for command of the sea, so that the opposing fleets may be considered as mirror images of one another. Command of the sea was the only thing worth striving for in the ‘Second Hundred Years’ War’, and Britain was the only enemy worth mentioning: in this view the historical function of the French and Spanish navies was to provide the Royal Navy with suitable opponents. These assumptions are extremely unsafe. As we have seen, there are good grounds for thinking that Maurepas and Patino were not planning to fight pitched battles with the British, and did not need ships designed for that purpose. The proper question to ask of all ship designs is not how well they compared with one another, but how well they corresponded to each country’s strategic priorities, and how wisely those priorities had been chosen.

Nor is it very useful to ask how ‘scientific’ the designs and designers of different countries were. It is still possible to encounter historians who put weight on the changing titles of the shipbuilders. In France ‘master carpenters’ (maîtres charpentiers) became ‘master constructors’ (maîtres constructeurs) and then simply ‘constructors’, before advancing to ‘constructor-engineers’ (ingénieurs-constructeurs) and finally becoming known as ‘naval architects’ (architectes navales), whereas in Britain warships were still being designed in the mid-nineteenth century by persons styled ‘master shipwrights’. The retention of a name drawn from the vulgar tongue, it is implied, must obviously indicate an unlettered craftsman confined to traditional rules, while a name derived from Latin must bespeak logic and education, and one based on Greek marks the summit of enlightened science. Perhaps it is still necessary to point out that the different titles of shipbuilders tell us something about their social aspirations, but nothing whatever about their working methods. Though British ship designers, like British professionals in comparable subjects such as architecture and engineering, continued to learn their business by apprenticeship until well into the nineteenth century, and though they were expected to spend a period working with their tools to understand the fundamentals of shipwrightry, the training they received in the mould lofts and drawing offices of the dockyards seems to have been in most respects as sophisticated as anything available in France.

There was, however, a real and important difference between Britain and France in attitudes towards ‘natural philosophy’, meaning science and fundamental knowledge in general. Mathematics lay at the heart of contemporary science, but mathematics was not an intellectually or socially neutral language. The mathematics of the ‘philosopher’ was pure mathematics: geometry, algebra, calculus. It was pure because it was abstract, and because it was essential to true science, that process of deriving universal truths from first principles, which Cartesianism prescribed. In social terms, this was the mathematics of the gentleman; one fully qualified for philosophy because he had no necessity to earn a living. It was very different from the vulgar utility of what in English was called ‘mixed mathematics’, the working calculations of men who had to work: men like bankers, tradesmen and navigators. The primacy of theory over practice, and of science over technology, was characteristic of France in the eighteenth century. The philosopher-mathematician alone was qualified to unravel the knottiest problems, and by tracing the fundamental machinery of nature he demonstrated his superior intellectual and social standing. ‘Tracing’ is the precise word, for geometry was a pure form of pure mathematics, and those whose subject could be expressed in geometrical terms enjoyed the highest scientific standing. It was a fundamental article of the Enlightenment faith that the philosopher was entitled and obliged to correct the work of the craftsman – this indeed was part of the official duties of the French Académie Royale des Sciences. As philosophers, gentlemen and mathematicians, its members were necessarily superior to mere practical experience. In naval architecture as in other domains, it was the duty of officers and philosophers to correct the vulgar errors of the shipwrights, by the application of pure mathematics.

The result was a series of studies by Leonhard Euler, Pierre Bouguer and others, deriving their prestige precisely from their remoteness from practical shipbuilding. The foundations they laid were built upon over the next two centuries to develop the modern science of naval architecture, but in the eighteenth century they had little to offer the shipwright. Most of their effort was devoted to the fashionable subject of hydrodynamics, and particularly the problem of the resistance of water to a moving hull, but since they ignored the existence of skin friction, which we now know to constitute virtually the whole of resistance at the speeds of which these ships were capable, their work had no practical value. More useful study was devoted to hydrostatics, which yielded the important definition of the metacentre, but French efforts to apply it in practice were not uniformly successful. The Scipion, Hercule and Pluton, launched at Rochefort in 1778 by Francois-Guillaume Clairin-Deslauriers, were among the first large French warships to have been designed on the basis of stability calculations. Unfortunately the sums were wrong, and the ships were too tender to carry sail. Much of their stowage had to be replaced by ballast before they could go to sea, sharply reducing their usefulness. Whatever else ‘science’ may have been doing in the eighteenth century, it was not an unmixed blessing to French naval architects.

One further general point about warship design needs to be made. Though ships may not have been directly comparable, naval architecture was highly competitive. Constructors constantly studied the designs of rivals at home and abroad, looking for ideas to borrow. In France and the Netherlands, so much less centralized in naval administration than Britain, these comparisons were often internal, between the rival traditions of the Mediterranean and Atlantic yards of France, and the admiralties of the United Provinces, but everywhere they were also international. All European navies were deeply involved in technical espionage, and in peacetime the French navy made a practice of sending its most talented constructors on extended visits to foreign, especially British, ports to learn everything they could. There is a particularly full and impressive report from the 1737 visit of Blaise Ollivier, master shipwright of Brest, with detailed comments on British and Dutch shipbuilding practice, much of which he admired and some of which he copied. All the European navies engaged in similar activities. In wartime they studied prizes; in peacetime they fished in the international market for warship designers. In 1727 the Admiralty of Amsterdam secured the services of three English shipwrights, with whose help it adopted ‘English-style’ designs – though naturally Rotterdam and Zealand declined to follow suit. In 1748 Ensenada, preparing to reform Spanish naval construction, sent Captain Jorge Juan on a major mission of industrial espionage to England. ‘His journey will be most useful to us,’ the minister wrote, ‘for in technical matters we are extremely ignorant, and what is worse, without realizing it.’ Juan returned with both information and a considerable number of shipwrights and artificers for the Spanish yards. English or Irish shipwrights became master shipwrights of Cadiz, Havana, Cartagena, Guarnizo and Ferrol. Throughout the eighteenth century the Danish navy, undoubtedly the world leader in technical intelligence, systematically collected copies of secret warship designs from every admiralty in Europe.

What seems to have been rare if not completely unknown in any navy was the literal copying of complete designs. Though statesmen and sea officers, impressed by foreign ships and ignorant of naval architecture, sometimes ordered ships to be built after the lines of a prize, it was in practice difficult if not impossible to do so. British hulls, for example, were more heavily timbered than French, so that a ship built in a British dockyard to the exact lines of a French design would displace more and float deeper. To maintain the same draught and freeboard, the British designer would have to adjust the lines, and so the ship would no longer be the same. In such cases the British designer might allow his superiors to believe that he had ‘copied’ a French design, or he might attempt to educate them in the complexities of naval architecture. Besides the lines, many other aspects of a foreign design would be changed to reflect British practice and requirements. The result might be a ship greatly influenced by foreign models, but it was never a slavish copy.

All these general considerations form a necessary background to any history of British warship design in the eighteenth century, but for thirty years, from the accession of George I in 1714 to the outbreak of war with France in 1744, British warships evolved slowly with little influence from outside. There were no Parliamentary votes for shipbuilding, so the practice of ’great rebuilds’ continued, though some of these ‘rebuilt’ ships were constructed years after their former selves had been broken up, in different dockyards, and without necessarily using any old timbers. The 1719 Establishment in principle dictated dimensions in detail, but in practice there seems to have been a slow but steady growth in dimensions. Some ships were built to the Admiralty’s 1733 proposal for a new and larger establishment, though it was never officially adopted, and the Ordnance Board blocked the heavier armaments which the Admiralty also wanted. Then the capture of the Spanish seventy-gun Princesa in April 1740, which took three British seventies six hours of hard fighting, caused considerable shock in Britain, and led to the adoption of a slightly larger 1741 Establishment, in conjunction with the heavier 1733 armament scheme. Soon afterwards the outbreak of the French war brought further shocks.

The main conservative forces affecting the British fleet were political and financial rather than technical. Neither the Navy nor Ordnance Board was enthusiastic about novelties which Parliament was not likely to favour, and still less likely to pay for. The Walpole administration kept up a large fleet, on paper and to a considerable extent in reality, and no one in the political world looked beyond numbers of ships to consider issues of quality and size. The Establishments were more an expression of this situation than an obstacle in themselves. The redoubtable Sir Jacob Acworth, Surveyor of the Navy from 1715 to 1749, did not take kindly to interference in the Navy Board’s business. ‘I have been in the Service fifty-seven years,’ he commented in April 1740 on complaints from Mathews,

and remember that the ships in King Charles’s time always decayed as fast, I am sure much faster, than they do now. But at that time, and long since, officers were glad to go to sea and would not suffer their ships to be complained of and torn to pieces in search for hidden defects.

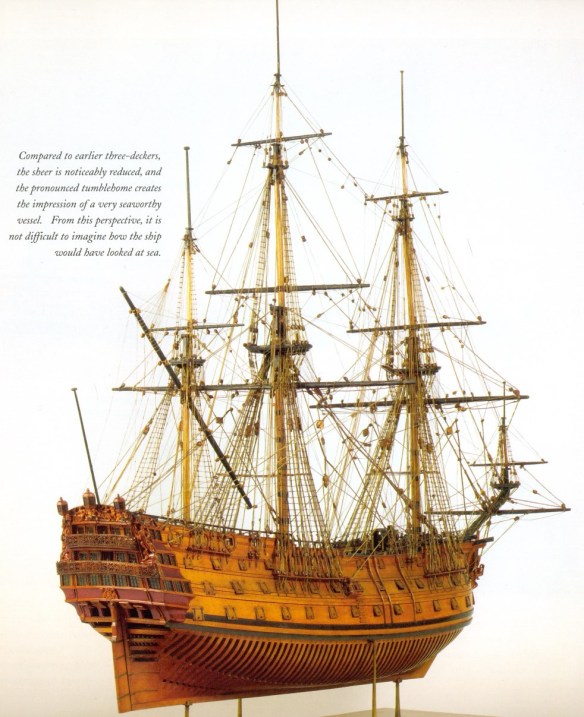

The admirals resented it, and many would have agreed with Vernon that ‘the arbitrary power a half-experienced and half-judicious Surveyor of the Navy had been entrusted with had in my opinion half ruined the Navy’. But Acworth was no unthinking reactionary. He designed a number of ships whose underwater lines were based on theoretical concepts developed by Sir Isaac Newton. They were not a great success – a little more conservatism might have spared the Navy an unhelpful intervention from abstract science – but in many respects Acworth was a designer of talent. His ideas about the unhappy three-decker eighty-gun ships of the 1690s, and indeed about all the older British designs, stressed the importance of reducing topweight to improve stability and weatherliness. This was completely sound, and the admirals’ reactions may not have been unconnected with the fact that the tophamper Acworth wanted to remove consisted largely of their cabins.

The Bedford Admiralty arrived in December 1744 determined to reform British ship design together with everything else. Their chosen instrument of reform was a committee of senior officers under the chairmanship of Sir John Norris, directed to draw up a new establishment, and specifically to replace the three-decker eighties with a two-decker seventy-four-gun design. Although the committee consisted mainly of members of the Board or known opponents of Acworth, it was entirely dependent on him and the master shipwrights for technical advice, and proved as much a brake as a spur to progress. It moved some way in the direction of greater size, but flatly refused to abandon the small three-decker. The ships of the 1745 Establishment turned out to share many of the deficiencies of their predecessors: cramped, crank, overgunned and leewardly.

This impasse was broken by the sensation caused by the prizes of the two battles of Finisterre, above all the new French seventy-four Invincible. Maurepas’ new fleet was built around these seventy-four-gun two-deckers, with a lower-deck battery of twenty-eight 36-pounders and a main-deck battery of thirty 18-pounders. Though the Invincible was by no means the largest in her class (the Magnanime, taken next year, was considerably bigger) she was 50 per cent larger in tonnage than the standard British seventy-gun Third Rate, and fired a broadside 75 per cent heavier. The differences between these British and French ships arose almost entirely from the difference of size. Naval architecture is a question of balance: if two competent designers build rival ships of the same tonnage and type, one can only gain a marked advantage in any one quality, such as speed or armament, by sacrificing the others. Even a modest increase in size, however, permits a significant improvement in quality all round, and a 50 per cent increase ought to translate into overwhelming superiority. But increased size naturally means increased cost. British naval agitation to match or copy French designs was not so much a technical as a political campaign, directed at Parliament, to finance bigger and more expensive ships.

The Finisterre victories came too late in the war to have an immediate effect, but in 1750 the Sandwich Admiralty secured the Privy Council’s authorization to vary the 1745 Establishment as they thought fit, which effectively marks the end of the British shipbuilding establishments. In 1755, just as the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War released the Navy Estimates from peacetime financial limits, Anson was able to appoint a Surveyor of the Navy of his own mind, Sir Thomas Slade. From this date the Navy was in process of rapid transformation into a superficially French-style line of battle based on seventy-four-gun two-deckers.

There remained important differences, however, between British and French warships. British ships continued to be somewhat smaller in tonnage and shorter, but more heavily timbered and fastened. Their rig and lines performed best in going to windward, and in heavy weather. They were built to stand the strain of prolonged sea-time at all seasons, they were stored for long cruises, and they were built to fight. They were also built to last; relatively cheap to construct and maintain, they were the rational choice of a navy which meant to surpass its enemies both in numbers and in stamina. Their rig, masts, sails, cordage, blocks, pumps, cables, steering gear and fittings of every kind were greatly superior in design and quality. French ships of all classes were lightly built of inferior timber, fastened with nails instead of trenails, but their very long hulls were highly stressed in a seaway. In fine weather these ‘battle-cruisers’ with their long hulls and taunt rigs were fast off the wind, but their performance fell off rapidly when close hauled, or when wind and sea rose. What was worse French designers seem to have had something of an obsession with reducing the depth and weight of the hull, which made their ships light and buoyant, but directly weakened resistance to hogging, sagging and racking strains. Worst of all they actually believed that the working of the timbers increased the speed of the ship. Consequently these ships had high building costs, high maintenance costs and short working lives, which made France’s low investment in docks and yards all the more expensive. In close action French ships with their light scantlings were a death trap.

Some French observers were aware of some of the deficiencies of their designs. A warship, one constructor declared,

ought to be fast, so everything is normally sacrificed to that. They are lightly timbered in order to be buoyant and carry their guns high; they have fewer and weaker fastenings because the play of the timbers makes for speed… it is to be feared that these principles lead the king’s constructors to build ships of the line which lack some of the qualities of a real man-of-war. They are afraid of losing their reputations, because the height of success for them is a fast ship which carries her guns high.

French dockyard officers had to pick up the pieces, literally. The constructors, complained the comte de Roquefeuil, commanding at Brest in 1771,

are all frauds. They build ships which are very light, very long and very weakly fastened because they sacrifice everything to speed and that is the way to get it. The first cruise gives the ship and her builder their reputation… [afterwards] we have to rebuild them here at great expense for a second commission by which time they have lost their boasted speed.

It is not even clear that sacrificing so much to hull forms which were fast in certain circumstances was actually the best way to get high speed in practice. Modern studies suggest that the possible differences in hull form, within the inherent limitations of wooden ship construction, cannot account for the wide differences in recorded performance. The smoothness of the underwater hull, which was a matter of cleaning or coppering (and hence of docks), and the infinite variations of rig and trim which were under the captain’s control, were almost certainly worth more. This explains how frequently British ships were able to catch French ones even in conditions which should have favoured them, and why French prizes taken into British service seem generally to have been faster after capture than before. Moreover prizes were usually significantly altered. The ships were always rerigged and rearmed, and the holds (especially of frigates) were rebuilt to give increased stowage to allow for prolonged cruising. The hanging of the decks, the siting of hatchways and magazines, the stowage of boats and booms, the position and design of pumps and capstans were often changed. These alterations produced substantially different ships.

Mention of frigates calls us back to the other important innovation in mid-eighteenth-century warship design. The new French battle-fleet of two-decker sixty-fours, seventy-fours and eighties were unquestionably built to a common plan imposed from Versailles, though the actual hull designs differed from yard to yard. Small cruisers, however, were beneath the minister’s notice, and the constructors were left to build more or less what they thought fit. It seems therefore that the Médée of 1740, commonly regarded as the first of the ‘true’ or classic frigate type which formed so prominent a part of all navies by the late eighteenth century, was a product of Ollivier’s unaided genius. The essence of the frigate in this sense was a small two-decker cruising warship mounting no guns on the lower deck. This made it possible to carry a battery of relatively heavy pieces on the main deck, high above the waterline, where they could be fought in bad weather, as well as lighter guns on quarterdeck and forecastle. This general arrangement was not new, in French or British service. In 1689 Torrington had proposed

that these new frigates should for rendering them more useful for their Majesty’s service, be built in such a manner that they should have but one size of ordnance flush, and that to be upon the upper deck, whereby they will be able to carry them out in all weathers.

The resulting class of Fifth Rates were soon overloaded with guns, in the British style. They were succeeded in 1719 by a class of Sixth Rates carrying a battery of twenty 6-pounders (ten ports a side) in the same arrangement, but they too tended to become overloaded with guns as British officers watched with concern the growth in the power and size of foreign warships. When the outbreak of war with France in 1744 exposed British trade to attack by French warships and privateers, the small, slow and cramped British cruisers aroused widespread dissatisfaction in the Navy. Once again it was French prizes which provided the leverage to dislodge the Navy Board’s opposition. ‘As all our frigates sail wretchedly,’ Anson wrote to Bedford in April 1747,

I entreat your Grace that an order may be immediately sent from your Board to the Navy Board to direct Mr Slade the Builder at Plymouth to take off the body of the French Tyger with the utmost exactness, and that two frigates may be ordered to be built with all possible dispatch, of her dimensions and as similar to her as the builder’s art will allow; let Slade have the building of one of them.

The Navy Board mounted a stout defence of the small forty-gun two-decker as superior to French cruisers like the privateer Tigre to which Anson referred, and they had some grounds to do so, for the French designs had all the characteristic French weaknesses, being very long and flimsy. When Ollivier’s Médée was taken in 1744 the Navy Board refused to buy her, so she was sold as a privateer, and soon afterwards fell apart in the open sea. This was not what the Navy wanted, and in spite of Anson’s request for exact copies of a prize, this was not what it got. The visible superiority of French cruisers, at least in speed, provided the Bedford Board with the leverage it needed to overcome the Navy Board’s resistance, and the co-operation of dockyard shipwrights of a younger generation than Acworth provided the technical backing – but what they produced were not exact copies of French designs. It is clear from the surviving correspondence that during the 1740s the shipwrights were carefully comparing prizes with the fastest existing British designs (notably the yacht Royal Caroline), and using the untutored enthusiasm of Anson and his colleagues to back a move from the old short two-deckers to the first British ‘true frigates’, with longer hulls (eleven or twelve ports a side) giving a twenty-two or twenty-four-gun battery, initially of 9-pounders. These very successful ships were inspired by French prizes in a political as much as a technical sense. The differences of British from French design philosophy and performance were even clearer in the case of frigates than of ships of the line.

Using the standard shorthand method by which all navies classified their ships by the number of guns, the early British frigate classes were mostly twenty-eights, which were followed in the Seven Years’ War by thirty-twos. In the case of frigates, however, the number of guns is not a good measure, partly because it included the light guns on quarterdeck and forecastle which could easily be changed, but mainly because it concealed the most important factor, the calibre of the main battery. Though a thirty-two does not sound much more powerful than a twenty-eight, the twenty-eights had a 9-pounder main armament and the thirty-twos, 12-pounders, giving a broadside 50 per cent heavier. These ships in turn were followed in the American War by the first 18-pounder frigates, rated as thirty-sixes or thirty-eights, but with more than double the broadside of the twenty-eights. It is therefore most useful to refer to frigates, as many contemporaries did, by their main battery calibre, and especially to distinguish the 18-pounder ‘heavy frigates’ from their predecessors.

The smaller cruisers known as sloops developed in parallel with the frigate, of which they were essentially miniature versions with one less deck, carrying their battery on the open upper deck. By the time of the American War many of the smaller sloops were rigged as brigs rather than ships. The two-masted rig economized significantly in manpower and was perfectly satisfactory for most purposes, though more vulnerable to damage in action. As an alternative it was possible to rig vessels of this size (200 tons or so) as cutters or schooners, which were even more economical in manpower, but whose very big sails required expert handling. Smallest of all sea-going warships were the gunbrigs and gunboats, built in considerable numbers for Channel patrols and local defence during the Great Wars.