Much as George loved horses, and much as he’d enjoyed his first skirmish driving a Dodge car, there was something about the tank that he just couldn’t get enough of. Its sheer brutal power and capacity for destruction appealed to his aggressive nature. There was nothing subtle about them, nothing that danced around the topic—the tank was a force of destructive power that knew nothing except to charge fearlessly into battle. Perhaps George felt a kind of kinship with them.

Either way, when the train hissed and puffed to a halt at the station where George stood waiting for it, it took all of his self-control to stop him from rushing up to it. A different officer might have stood and watched as the tanks were backed off the train, but George went straight into the first tank, driving it himself with typical hands-on enthusiasm. There was also one practical consideration: George was the only American present who had any experience driving tanks at all.

Earlier in the year, George had been sent to Liverpool as Pershing’s personal aide. When Pershing was sent to Paris, George followed him there, where he’d spent three months overseeing the training of American troops there. After that he was moved to Chaumont and oversaw the base. All this training and organizing was something he found intensely boring; he implored Pershing to get him to the front lines and into the thick of the action, and Pershing did his best. With cavalry being used less and less, Pershing aimed to give George command of an infantry battalion. At that point, George didn’t care what he was allowed to command as long as he could get into the fighting. As British Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig described in his diary after meeting the young man, he was “a fire-eater, and longs for the fray.”

As George himself started hunting for a different position in the army, the idea of working with tanks started to occur to him. At first, he was strongly opposed to them and preferred the cavalry that he’d grown up with, but gradually, he started to warm to the idea. One aspect that appealed to him was that the troops inside the tanks were kept a little safer from gunfire than most other soldiers. George himself appeared to have no fear for his life and never did, but he wrote to Bea that “I love you too much to try to get killed.”

When he came down with jaundice and had to be admitted to hospital, George was no doubt frustrated by even more idleness. But it was in the hospital that he met Colonel Fox Connor. Connor was a great commander in his own right, but he is best known for his mentorship of young officers that would later become prominent in World War II; he was the man who made Eisenhower. He immediately recognized a fighter in George and encouraged him to work with tanks.

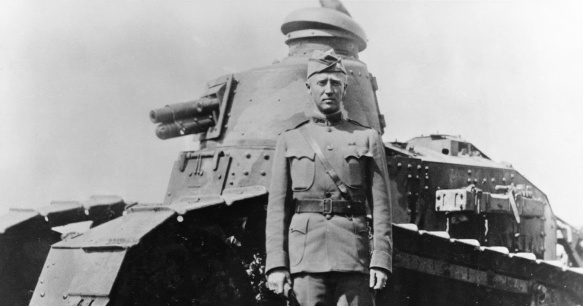

Finally, on November 10, 1917, George was given his assignment to establish the AEF Light Tank School. After being trained by the French army at Champlieu, studying the results of the Battle of Cambrai, and going to the Renault factory to watch the tanks being made, George was finally ready to teach his fellow Americans how to drive tanks.

On April 3, 1918, shortly after his precious borrowed tanks had arrived at the Tank School on the train, George was promoted to lieutenant colonel. In between attending the Command and General Staff College in Langres, he also trained his men to use tanks in support of infantry. In this period, he wrote a 58-page paper on light tanks. His childhood tutors would probably have fainted to discover that their “dimwitted” pupil had just written the basis of the US Tank Corps, dyslexia or no.

Even considering his demonstrations were going well and inspections of the Tank School had rendered others impressed, George was still bored; he longed to be on the actual front, in the thick of the fighting. Major LaFavre, a Frenchman, finally indulged the fiery young commander by driving him to the German front for a look at the battle. Although George didn’t actually get to fight, he did take off his helmet and have a smoke to insult the Germans.

Finally, in August 1918, George was given command over the 1st Tank Battalion and sent along with the rest of the Tank Corps to the railroad through St. Mihiel to Verdun. They were to free the railroad, allowing for the establishment of a new base. George was to go into battle at last. His speech the night before the fight was to the point: “American tanks do not surrender.”

September 12, 1918, would be George’s first taste of a world war. He waited in his tank behind the front lines, listening to the shelling. At first, he was nervous about sticking his head out of the parapet, but within a few hours of the fight starting, George was bored of waiting. He climbed out of the tank and headed into the thick of battle on foot.

This day would be one of the best of George’s life: reckless, dangerous, characterized by rash decisions, and endlessly exciting. He marched fearlessly across a bridge that was presumed to be mined (it wasn’t), hitched a ride on random tanks that he came across, and spent a few hours hiding in an open shell hole – a hole blown in the earth by an explosive shell – after diving off a tank that was being violently fired on. He escaped the shell hole by traveling across the battlefield, listening for the sounds of the machine guns and throwing himself to the ground anytime he heard the machine guns open. He described his calculation of the time between the guns opening and the bullets arriving as “the only use I know of that math has ever been to me.”

He returned to his ranks later that afternoon to happily organize an attack on a small town called Beney. Even discovering that his food hamper had been replaced with rocks by some courageous prisoner of war wasn’t enough to dampen George’s enthusiasm; he simply pinched some crackers off a dead German and carried on with his organizing.

The next day, Patton adopted what would be his characteristic method of leadership: leading from the front. Walking in front of his tanks as an inspiring example to his men, he led his troops to victory, capturing Jonville on September 14. The battle had been a great triumph for the Allies and especially for George. Only five of his men had been killed in the battle, and the success of the tanks had proven to high command that they were more than useful—in the right hands though.

And it was largely agreed that George’s hands were about as right as they could get.

A Purple Heart for George

September 26, 1918 dawned with thick fog and even thicker enemy fire.

The hoarse crack of German machine guns filled the sky as George led his brigade towards Cheppy, determined to clear out those nests of guns and clear the way for the U.S. I Corps, who followed behind. A hundred and fifty tanks rumbled on behind them; George led the way on foot, watchful among the heavy fog. It shrouded the landscape, hiding the hulking shapes of enemy guns, muffling their crack so that the loudest sound seemed to be the eerie rumble of the tanks that followed them.

At George’s side, his orderly, Private First Class Joe Angelo, strode along with not a care in the world. At only twenty-two, he was as fresh-faced as a young boy. Gun tucked close to his body, he kept one eye on the enemy and one on George.

A crossroads emerged from the fog as they advanced. George gestured sharply, bringing the men and tanks to an abrupt halt. He listened for a moment to the sound of the machine guns before turning to Joe and speaking in a low voice. “Stay here and watch for the Germans,” he ordered. “I’m going on ahead.” Before Joe could protest, George shifted his gun and headed on up the knoll ahead, scanning the shrouded landscape for sign of the enemy. He was determined to flush out those nests of sinister enemies and destroy them with the power of his tanks. The loudest sound in the muffling mist was his own harsh breathing as he advanced slowly, leaving his fifteen men behind.

The deafening whistle of a shell split the silence. George flung himself to the earth as shells hurtled above him; he heard the crack and thunder of their explosions behind him and prayed that his men and tanks were safe. Then, a familiar shot rang out from somewhere near the crossroads—the sound of an American rifle discharging. Adrenaline stung George’s hands and feet and he scrambled back over the knoll, shouting, heedless of the Germans all around.

“Joe!” he yelled. “Is that you shooting down there?”

Joe’s response was lost in the chaos of machine guns and shells that broke loose, the air shattered with bullets and explosives. It was as if the clouds had burst and were raining death down upon them. George hurried over the knoll in time to see him gesture with his rifle towards the body of a German soldier that lay nearby in a pool of blood. George’s blood was on fire.

“Come on!” he yelled down to Joe. “We’ll clean out these nests.”

Joe scrambled up the hill beside his commander and they advanced together towards the ranks of German machine guns, expecting their tanks to emerge from the fog and reinforce their attack at any moment, but no support came. A heavy spatter of machine gun shots sent them both diving for cover. George cursed. “Why aren’t my boys taking out these nests?” he snapped. “Joe, go and find out what’s going on back there.”

Joe was back almost as quickly as he’d disappeared, running half-crouched to avoid the screaming bullets. “The tanks are stuck in the mud, sir!”

George swore again. “Follow me.”

They crawled, then ran, back to the tanks, which were sunken to the hubs in mud. George seized a shovel and started digging, yelling at his men and at Joe to hurry up and help. Sweat poured down the back of his neck as he worked manically, aware of the shells that struck ever closer, sending up sprays of earth. Half-deafened by the chaos, George looked up at last to see his tanks moving again. More by gestures than words, he urged them forward and led them back up the hill. Now they could return fire and the world dissolved into one continuous blast of noise.

Halfway down the other side of the hill, they spotted a huddle of infantrymen among a scattering of bodies. They turned their terrified faces to George, clinging to their guns and each other with pale shadows of that morning’s bravado.

“What are you lot doing?” George roared at them.

“We don’t know what to do, sir,” one cried plaintively. “Our officers are all dead.”

“Joe, take these men to the tank detachment,” George barked. The infantrymen hurried over to Joe, delighted to finally have leadership; the fact that it came in the form of a Private First Class like themselves did not occur to them. Joe led them quickly back to the tanks. Heavy fire from the German artillery continued to pound into the American ranks. Seeing that they were drawing all the fire, George yelled for Joe again. “Go ‘round the side and wipe out those German nests,” he ordered. “Take fifteen men with you.”

Joe’s eyes were two terrified white circles in his dirty face. “I’m sorry, but they’ve all been killed.”

Despair filled George for a moment. “My God! They’re not all gone?”

“I’m sorry, sir. They’ve all been killed by machine guns.”

George gritted his teeth, fire rising in him on behalf of the brave men that had all perished. “I’ll clear them out myself,” he growled, seizing his gun and heading for the heaviest fire.

“Sir! No, sir!” Joe lunged forward and grabbed George by the arm. “It’s suicide!”

George grasped a handful of Joe’s dark, wavy curls where they stuck out from under his helmet and shook him so hard that the young man’s teeth rattled. “We’re going,” he said and plunged into the fog. Joe was right behind him. Blood seething, George charged forward. Then a muzzle flashed in the mist, terribly close. George heard the crack and felt something shatter in his thigh. He stumbled to a halt, barely comprehending, as pain began to blossom through his leg. When he looked down, a round circle of blood had opened on his leg.

“Sir.” Joe was beside him.

George could say nothing. He collapsed without a sound.

With bullets raining around them, it was young Joe who pulled the unconscious George to safety, despite the danger he was placing himself in. He dragged his commander to the nearest shell hole and bandaged the wounds in his leg: the entrance wound in his thigh and the ugly exit wound in his left buttock. For two hours, George lay senseless in the shell hole as Joe kept watch. When he revived, his first concern was for the battle. Lying in the mud and blood, he swiftly took command of the battle. Joe was instrumental; he ran back and forth between George and the tanks, carrying his orders all over the battlefield despite the peril. It was only after those German nests were finally destroyed that Joe was allowed to find some infantrymen to help carry George out of the shell- hole and to safety. And George would only allow himself to be taken to a hospital once he’d given his report to a command post.

George received the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions that day, as well as a Purple Heart when the award was established in 1932. Joe was also awarded a Distinguished Service Cross, but perhaps the highest title he could lay claim to was the way that snobbish George chose to describe his low-born orderly: “without doubt the bravest man in the American Army.” He told American newspapers in 1919 that he had never seen Joe’s equal.

George’s wound meant the end of World War I for him. While he was promoted to colonel not long after his part in the battle, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive – as the battle would be known later – would prove successful. The victory came at a high price, in both lives and currency; in only three hours, the Allies alone used more ammunition than was fired in the entire American Civil War. The offensive would continue for forty-seven days and cost almost sixty thousand German and American lives alone. But on November 11, 1918, an armistice would finally bring an end to the First World War.

George stayed in Europe recuperating from his injury until March 1919. Then he was sent home to Camp Meade, Maryland to serve as a major. In June he was sent to Washington, D. C. to write manuals on the operating of tanks. Here he started to revolutionize the strategic use of tanks in the American army, assisted by Dwight D. Eisenhower, who would later become the Allied commander of the Second World War. George and Eisenhower forged a partnership that would prove formidable in the war that was coming.