When Jordan became an independent country in 1946, the Legion became a regular army but continued to receive British subsidies, supplies, and advice. During the conflict in 1948, under Glubb Pasha, it was instrumental in King Abdullah I’s military successes in areas that the Partition Plan had allotted to the Arab Palestinian state as well as in East Jerusalem. Other Arab countries and Palestinians blamed the Legion for its failure to prevent the formation of the Jewish state and for the limited and restricted Arab advances on the eastern front.

Bowing to nationalist and anticolonialist elements in the region, on 1 March 1956 King Hussein of Jordan dismissed Glubb Pasha. Thus the leadership fell into the hands of Jordanian commanders and, in 1969, the Legion was renamed the Jordanian Armed Forces.

After taking over the region called Transjordan after World War I, Great Britain found it necessary to create a local military force to defend the territory against both internal and external threats. In October 1920 the British created a unit of 150 men, called the Mobile Force, under Capt. Frederick G. Peake. Transjordan was in a state of relative anarchy at that time, having experienced many centuries of benign neglect under the Turks. Thus, when Amir’Abdallah ibn Husayn, descendant of the Prophet and the son of the Hashimite Shaykh of Mecca, arrived in 1921 with the intent of making himself king (with British approval), he was not universally welcomed despite his lofty pedigree. Almost immediately, ‘Abdallah was forced to suppress a series of tribal challenges to his rule. His security problems forced him to turn to the British for help in late 1921, and London agreed to expand the Mobile Force under Peake to meet Abdallah’s military needs. Between 1921 and 1923, the British built up the Mobile Force-renamed the Arab Legion – to a reinforced battalion in strength and used it to crush a series of tribal revolts throughout the country. Nevertheless, beginning in 1922, Arabian Ikhwan warriors under ‘Abd al-Aziz Ibn Sa’ud began raiding Transjordan, eager to expand the areas they had conquered for their Wahhabi interpretation of Islam. Royal Air Force (RAF) aircraft and armored cars were dispatched to Transjordan and, together with the new Arab Legion, succeeded in stopping the tide of Saudi expansion.

By 1926, Peake’s Arab Legion had accomplished a great deal. The force had grown to about 1,500 men and officers. A small number of the officers were British, but the rest, and all the enlisted, had been recruited from the settled villages of Transjordan. (The Transjordanian towns supported ‘Abdallah’s centralized rule and the security from Bedouin raiding it promised.) The legion had decisively defeated several of the more aggressive Arabian tribes, which had prompted Ibn Sa’ud to rein in his forces from further attacks on Transjordan. Finally, by crushing the various tribal revolts, the legion had forcefully asserted the strength of the monarchy and demonstrated its ability to rule the Bedouin tribes.

Between 1926 and the outbreak of the Second World War, the British decided to exert greater control over the Arab Legion and to rationalize their own force structure in the Middle East to reduce the costs of empire. The legion was reduced in strength, placed under the command of the British high commissioner in Jerusalem, and relegated to internal-security duties. The RAF presence in Transjordan was also greatly reduced. Finally, a new force, called the Transjordan Frontier Force (TJFF) was created to take over the external-security responsibilities previously handled by the legion and the RAF. The TJFF was created in the image of the British Indian Army, with all billets above the rank of major held by British officers. But the TJFF proved less successful in policing the borders against raids by Saudi and Iraqi tribes than had the Arab Legion. In response, Capt. John Bagot Glubb was made Peake’s second in command in 1930 and ordered to raise a “Desert Mobile Force” to deal with the raiding tribes. Glubb enjoyed great success recruiting Bedouin tribesmen to serve in the new force, which he employed more in the manner of a nomadic warrior band (albeit one with trucks and armored cars) than a conventional Western military force. Glubb’s outfit succeeded in once again pacifying Transjordan’s borders.

World War II saw the Arab Legion grow into a professional military. The small size of the British army at the start of the war forced London to scrounge ground forces wherever it could to meet the wide-ranging Axis challenges. The Arab Legion became one of the beneficiaries of Britain’s desperation. Both the Desert Mobile Force and the TJFF were amalgamated into the legion, which by the end of the war had grown to a force of nearly 8,000 men and officers. The heart of the army was a 3,000-strong mechanized brigade (built from the core of Glubb’s Desert Mobile Force) and the Desert Patrol Force of 500 men.’ The legion was then commanded by Glubb and officered largely by British regulars, seconded from the British army. In addition, the legion had gained some combat experience during the war. Elements of the legion, including the Desert Mobile Force, participated in the British campaigns to overturn the anti-British Rashid ‘Ali government in Iraq as well as the conquest of Syria from Vichy France. Other units of the legion were posted to garrisons throughout the Middle East to free up British regulars and other Commonwealth troops for combat duties, and the Arab Legion briefly trained for duty in Egypt, where they were to have been deployed had the Germans not been turned back at El Alamein.

The War of Israeli Independence, 1948

In 1948, when the Arab Legion marched into Palestine, it was the most professional indigenous military in the Middle East. Jordan’s army was trained and led entirely by British officers or Jordanian officers trained in the British manner. In fact, all but five of the officers of the rank of major or higher were British, including Glubb, who remained its commander.’ The British saw to it that the legion was well prepared for conventional military operations. During the first twenty-four years of its existence, the Jordanian army was responsible for both internal and external-security duties, but regardless of other priorities, Jordanian soldiers and officers constantly practiced for combat operations against organized militaries. Moreover, during the Second World War, internal-security duties and even combat against Arabian tribes had taken a backseat to the need to prepare the legion for combat with the Iraqi army, the Vichy French, and the Germans.

Ultimately, the British built the Jordanian army in their own image – or at least in the cherished image of Britain’s vanished colonial forces. Just as Britain traditionally relied on a small, long-term-service professional army, so too did Jordan. Just as Britain traditionally relied on a purely volunteer force, so too did Jordan. Just as the British emphasized the quality of their manpower rather than its quantity, so too did Jordan. Just as the British stressed the skills of the individual soldier honed in constant practice over many years, so too did Jordan. In Nadav Safran’s words, “excellently drilled and ably commanded by British officers it was then [1948] a model of the level of effectiveness that could be achieved with Arab soldiers through careful training and organization.”

The Jordanian Armed Forces on the Eve of War

As a result of this British tutelage, the Arab Legion in 1948 was a highly motivated elite body of long-term-service professionals. Glubb purposely insisted that the legion remain all volunteer so that it could retain its carefully nurtured esprit de corps. In 1948, Jordan was one of the most backward regions of the Arab world, and the pay of an enlisted man was almost a princely sum. In addition, the military was considered a prestigious career among the Bedouin. The combination of the legion’s prestige, economic benefits, and esprit contributed to a very high retention rate, with many personnel serving for decades and many sons of legionaries following their fathers into the king’s service. Moreover, by keeping the force small, the legion had its pick of new recruits and was able to man its ranks largely from Transjordan’s minority Bedouin population, whom the British believed made better and more loyal soldiers. Last, the small size of the army allowed Jordan to continue to provide high-quality training for its troops.

Nevertheless, the Arab Legion did have its problems, mostly related to the economic backwardness of the country. Because Glubb favored the Bedouin over the Hadari townsmen, the tribesmen made up at least 50 percent of legion strength (although they represented no more than 30 percent of the larger Jordanian population). Unfortunately, the Bedouin rarely had an education, so literacy was almost nonexistent among legion recruits. Even fewer had any technical background. Most had never owned anything more complicated than an ancient bolt-action rifle. Of course, the Hadari had had greater exposure to machinery than the Bedouin, and so they were heavily represented in the mechanical-support branches, but this advantage was entirely relative, and few had any true technical training. Moreover, the legion suffered from friction between the Bedouin and the Hadari, and the British were forced to mostly segregate the two groups into separate units to prevent them from feuding.

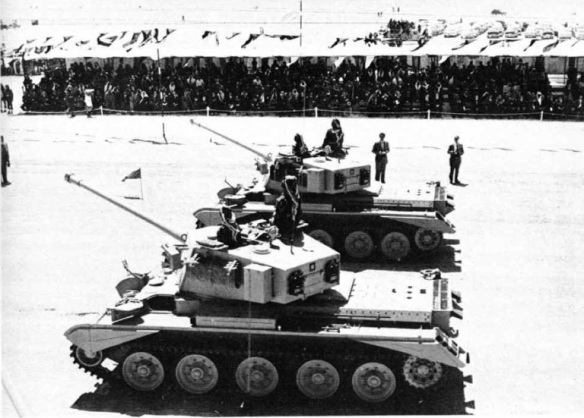

At the outbreak of war in May 1948, the Arab Legion had 8,000 men, fifty British armored cars, and about twenty artillery pieces. As paltry as this arsenal may seem, it greatly exceeded that of the Israeli Haganah units they faced. For example, in the initial battles around Jerusalem, to which the legion committed nearly half its strength, the heaviest weapons the Israelis possessed were two medium machine guns and two Plat shoulder-fired antitank weapons. For the war, Glubb formed the legion into a single divisional command with two brigades, each of which had two battalions of infantry, as well as a number of independent infantry companies. An armored-car company was attached to each infantry battalion. The artillery was organized as a separate battalion with three batteries. Finally, a third brigade was organized as a “dummy” formation to fool the Israelis into believing that another brigade was in reserve to deter them from launching a counteroffensive against Transjordan itself. The most significant material problem the legion faced was a shortage of ammunition. Before the outbreak of fighting, Glubb estimated that he had only enough rounds for one short battle if it involved the entire division. Against this force, the Israeli Haganah could field 50,000 poorly armed and mostly untrained troops. No more than half of this force was organized into the nine Palmach and Haganah field brigades ready for deployment anywhere in Palestine. The rest were regional militia that could only be used to defend their town or settlement. At the start of the war, the Israelis had no real armor, artillery, aircraft, or even heavy crew-served weapons to speak of. Moreover, the Jews had to spread these forces to fend off five other Arab armies in addition to the legion.

Jordanian Goals and Strategy

There is considerable uncertainty regarding King ‘Abdallah’s intentions when he ordered the invasion of Palestine in May 1948. It is clear that he did not hope to eradicate the Jewish state altogether, unlike his Palestinian, Syrian, Egyptian, and Iraqi allies. At least initially, in 1947, it appears that ‘Abdallah hoped only to occupy the parts of Palestine reserved by the UN commission to the native Palestinians and annex them to his own state. At that time, the monarch opened secret negotiations with the Israelis intended to reach an accommodation that would allow him to divide the territory with the Jews without bloodshed. As time went by, however, his ambitions appear to have grown. He apparently began to desire that the new Jewish state be reduced to an autonomous region of Jordan. Barring that, ‘Abdallah hoped to increase the amount of territory under Jordanian control and, in particular, he seems to have wanted to control Jerusalem rather than leaving it an international city as specified by the UN partition plan. It might be most accurate to say that ‘Abdallah intended to conquer the West Bank territories and then take whatever else he could if the opportunity arose.’

‘Abdallah’s intentions were complicated by the limited military forces at his disposal and by the divided loyalties of his British officers. On the one hand, the Arab Legion simply was not large enough to occupy all of Palestine; it was not even large enough to conquer the various parts assigned to the Palestinians by the UN. On the other hand, the Israelis could be expected to fight tooth and nail, and Jordan could not be sure how its ostensible Arab allies would react to blatantly self-serving moves. Beyond this, ‘Abdallah was completely dependent on Glubb and the other British officers, whose loyalties were divided between Amman and London. The British government made it clear that, although they had little love for their erstwhile Jewish subjects in Palestine, they would not tolerate actions in contravention of the UN settlement. London specifically ordered all of the British officers seconded to the Arab Legion “to abandon their units if these invaded Jewish territory.”

In the end, Jordanian strategy attempted to straddle these competing positions. Glubb intended to push into the West Bank immediately and occupy it up to the international borders declared by the UN. The legion would then shift to the defensive as quickly as possible to avoid unnecessarily provoking the Jews and to secure the Palestinian territories as soon as they had been taken. One final consideration in Glubb’s approach was the need to minimize his own casualties. A problem with having a small, long-term-service professional army was that casualties were not easily replaced. Consequently, Glubb wanted to avoid bloody battles at all costs, particularly in the streets of Jerusalem, where the training of his troops would be discounted and many might be killed in house-to-house fighting.

Course of Operations

The first Jordanian combat operations actually occurred before the outbreak of war on 14 May 1948. Israelis from the four Etzioni settlements outside Jerusalem began harassing Arab military movements during April 1948. The British considered these actions intolerable and had sent British regulars with tanks and backed by a reinforced company of the Arab Legion plus Arab irregulars to attack these settlements in early May. Remarkably, the Jews held their positions against the assault, but the British still decided that they had taught the Jews enough of a lesson and withdrew their own forces. The Arab Legion company and the Palestinian irregulars remained, however, hoping to receive orders from Amman to resume the attack.

A week passed, and on May the company commander, Col. Abdallah at-Tel, took matters into his own hands and ordered an attack on the settlements. The Jews had about Soo able-bodied settlers (men and women) in the four settlements but had only small arms. While the Arab force was somewhat smaller, it was centered on the legion company and was backed by a squadron of armored cars as well as considerable artillery and mortar support. In three days of fighting, the Arabs succeeded in isolating the four settlements, and then the legion company assaulted the main settlement of Kfar Etzion with heavy-fire support. The Arabs used part of their force to pin the Israeli defenders along their main line of defenses, and then sent another portion with the armored cars to outflank the primary Jewish positions. On 13 May the legion was able to take Kfar Etzion, prompting the other three settlements to surrender.

The main body of the Arab Legion crossed over the Jordan River into Palestine on the morning of 14 May 1948. There they linked up with the Jordanian troops already operating south of Jerusalem and quickly occupied the superb defensive terrain of the Samarian hills. Glubb deployed one of his brigades to cover the entire area from Janin to just north of Ramallah, which allowed him to concentrate his other brigade, plus a num her of independent infantry companies, in and around Jerusalem and establish brigade headquarters at Ramallah.

THE BATTLE OF JERUSALEM

On 1 7 May King ‘Abdallah ordered Glubb to attack Jewish Jerusalem in strength. This was a clear contravention of both the UN plan and the orders of the British government. Nonetheless, Glubb reluctantly complied, rationalizing it simply as intervention to end the confused fighting that had been raging in the city for the last three days. He detached one of the battalions sent initially to Samaria, the 3d Infantry, from its parent brigade and ordered it back south to Jerusalem to take part in the attack on the city. The Jordanians then launched a coordinated attack from both north and south of town with a supporting thrust against the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. From the north, Glubb sent the 3d Infantry – supported by armored cars, artillery, and mortar batteries -into the Shaykh Jarrah area of northeastern Jerusalem. In the center, several companies of the legion bolstered by Palestinian irregulars were ordered to assault the isolated Jewish Quarter and either overrun it or besiege it. Meanwhile, the Jordanian units that had come up from the Etzioni Bloc (since reinforced to about a battalion in strength), tried to envelop Jerusalem from the south by attacking the settlement of Ramat Rachel on the road to Bethlehem.

The legion’s northern thrust met initial success but then was brought to a halt by fierce Jewish resistance. The Israelis had only seventy members of the Irgun Zvi Leumi, the freelance militia-terrorist group headed by Menachem Begin, in Shaykh Jarrah. This small force was easily overpowered by the legionaries, thereby cutting off the Jewish garrison on Mount Scopus. The Jordanians then attempted to drive westward, from what would later be known as the Mandlebaum Gate, to surround the Old City and cut it off from Jewish territory. Although the Arab Legion had a huge advantage in firepower – the defenders had only a pair of light machine guns and two antitank weapons – they could not break through the Israeli positions. After their initial rebuffs in this sector, the Jordanians shifted their effort closer to the Old City. The legionaries employed excellent combined-arms tactics, moving in teams of infantry and armor supported by mortar fire and, occasionally, artillery when practical. Nevertheless, they found the going very tough against the under armed, but resourceful, Israelis. Eventually, the course of the fighting centered on the Israeli-held monastery of Notre Dame de France at the northwest corner of the Old City. Although it was defended by no more than a handful of Israelis with only one Plat antitank weapon and a handful of rounds, the Jordanians could not take the position. They lost several armored cars to Israeli Plat rounds and Molotov cocktails, and their battalion suffered nearly 50 percent casualties. Late on 24 May, Glubb called off the attack, fearing additional losses. The legion effort north of the Old City then slacked off considerably until the first UN-brokered ceasefire halted fighting altogether on 10 June.

The southern thrust of the initial Jordanian offensive, against Ramat Rachel, was conducted in conjunction with Egyptian units and was even less successful than the northern assault. Elements of the Egyptian invasion force had marched across the Negev Desert to Beersheba and then on to Jerusalem, where they linked up with the units of the Arab Legion south of the city. On 21 May the two Arab armies launched a combined assault against the small Israeli force defending the village on the hills south of Jerusalem, driving out the defenders by sheer weight of numbers. However, later that day, a company of the Haganah’s Etzioni Brigade reinforced the Israelis, who counterattacked and retook the village. Over the next three days, the Arabs attacked the settlement over and over again, recapturing it several times only to lose it to Israeli counterattacks each night. On 24 May reinforcements dispatched by Glubb arrived at Ramat Rachel to restart the flagging offensive. In the ensuing battle, the legionaries and Egyptians once again managed to storm the kibbutz, but the Israelis also brought up reinforcements and retook it early the next day. In that counterattack the Israelis also succeeded in taking a nearby monastery that dominated the surrounding terrain and that had served as a jumping-off point for the Arab attacks on Ramat Rachel. With the loss of this key base of operations, the Egyptians and Jordanians called off their attack and dug in, ending their joint effort to envelop Jerusalem from the south.

Only in the center, against the Old City, was the Arab Legion able to secure its objectives. The Jewish Quarter had the disadvantage of being surrounded by Arab-controlled territory and cut off from the Jewish section of the new city. However, it had the advantage of being an ancient Middle Eastern madinah, overbuilt with adjoining houses and cut by narrow winding streets that were easy to block or defend. While the British were in Palestine, the Israelis had smuggled a small amount of supplies and some Haganah and Irgun soldiers into the Old City so that it could withstand the inevitable assaults and likely siege they expected would follow the British withdrawal. The Arab Legion attacked the Old City on all sides on 16 May, slowly overpowering the small number of defenders and forcing them to give ground. The Israelis attempted a relief operation during the night of 17-18 May. This effort was badly bungled and turned into a frontal assault on Arab Legion positions. The Jordanians proved to be excellent marksmen and inflicted heavy casualties on the Israelis. Nevertheless, the main attack so diverted the legionaries that another force was able to surprise and overpower the Arab irregulars guarding Mount Zion and then breach the Zion Gate into the Jewish Quarter. Although the legion was surprised by the operation, they quickly regrouped and counterattacked the Israeli forces holding open the Zion Gate. In a brief, fierce fight during the day, the Jordanians defeated the Israelis and again shut off the Old City from the Jewish-held sector. For the next ten days, the Israelis tried to open a corridor to the besieged Jewish Quarter, but all of their attacks failed. The legion devised a very effective tactic of allowing the Israeli soldiers and sappers to penetrate through the Zion Gate and then trap them in a kill sack in the small courtyard on the Arab side of the gate. Meanwhile, inside the Old City, the legion conducted a highly effective clearing operation. The Jordanians did an excellent job, using armored cars in conjunction with small infantry teams and support from mortars and direct-fire weapons on the city walls. They pushed deeper and deeper into the Jewish Quarter, defeated several more Israeli relief efforts, and finally compelled the defenders of that sector to surrender on 28 May.