As in the fall of 1990, however, in the fall of 2002 the White House felt obliged to seek formal domestic and international approval for the impending showdown. The administration would probably have gone ahead without such approval, but tried to get it for two reasons: there was an outside chance the efforts might head off war (by scaring Saddam straight), and even if they did not, they could increase support for the administration’s policy at home and abroad.

When Congress returned from its summer recess, accordingly, the administration pressed for congressional backing for a hard line, and in early October the House and Senate duly passed a resolution authorizing the president “to use the Armed Forces of the United States as he determines to be necessary and appropriate” to “enforce all relevant UNSC resolutions” and “defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq.” Secretary of State Colin Powell, meanwhile, had convinced Bush to go through the United Nations rather than around it, and in early November, the administration was able to secure a fresh Security Council resolution declaring Iraq “in material breach” of previous resolutions and demanding new weapons inspections.

As the public debate played out during the fall and winter, the administration finalized its plans for the war and aftermath. The deputies committee had been kicking around three postwar models—a quick transition to Iraqi control, a military administration run by Centcom, and some kind of civilian-led transitional authority—but during the fall, the administration opted for the first. In October, the NSC approved the idea of putting a single cabinet official—the secretary of defense—in charge of all postwar planning and operations, both military and civilian. Rumsfeld directed Undersecretary of Defense Douglas Feith to set up an office to handle the civilian efforts, but then canceled the instruction a few days later (apparently following instructions from Bush to make sure that postwar planning maintained a low profile and did not get in the way of the administration’s diplomatic efforts). On December 18, unsatisfied by the response the Iraqis had given the United Nations about their weapons programs, Bush told his top advisers, “I think war is inevitable.” At this point, Rumsfeld instructed Feith to set the civilian postwar planning office in motion, and the result was a formal presidential directive on January 20, 2003, establishing the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, to be led by retired Lieutenant General Jay Garner.

On January 24, Franks delivered his final war plan to Rumsfeld, but the postwar pieces were still up in the air. Centcom was formally responsible for maintaining security in Iraq, but it continued to act as if somebody else were going to handle the job. Worried about Cent-com’s lack of planning, the Pentagon’s Joint Staff had set up a special task force to assist it, but the late, unappreciated, and under-resourced initiative never got anywhere. And Garner’s hastily thrown together ORHA team was scrambling to figure out what was going on.

In late February, Garner brought together officials from across the administration to run through how things would play out once the fighting stopped. For those with eyes to see, the exercise was sobering. Expectations of what officials would find waiting for them in terms of human and physical infrastructure were high and major issues were still unresolved. The official summary noted several “show-stoppers,” problems that could spell mission failure if not resolved, including:

- Failure to obtain interagency agreement on role and mission of ORHA and other agencies.

- US/Coalition military does not act as police until relieved by competent indigenous civilian police.

- Key policy decisions not made, i.e., applicable law, size of U.S. “footprint” in justice sector, operations vs. development.

- Early reestablishment of public order under rule of law is critical to success but is achievable only if funds and staff are made available now.

Despite lip service paid to the importance of such issues, however, little was actually done about them. Postwar security in particular was left an orphan, with nobody taking responsibility for providing it. Administration leaders apparently assumed that it would be a relatively small problem that could be handled by the remnants of the Iraqi state, newly available foreign forces, or some other deus ex machina. On March 10, the president approved plans for an Interim Iraqi Authority to take over from Centcom and ORHA soon after the war ended, but just what this would involve in practice—or how it would relate to the still-unresolved security problem—was never elaborated. On March 17, Bush gave Saddam a final ultimatum: leave in forty-eight hours or else. And when Saddam stayed put, two days later the president made good on his threat.

ONCE MORE UNTO THE BREACH

Although the war was a rematch and might have been expected to follow a familiar script, the U.S. military was determined to fight differently this time around. Under intense pressure from Rumsfeld, Franks had developed a plan for attacking quickly, comprehensively, and decisively. There would be no slow buildup of large forces in theater; no lengthy preliminary aerial bombardment; and no deliberate set-piece battles. Instead, the air and ground attacks would start at the same time; operations would be truly joint, with all combat arms working together toward a common end; and a premium would be placed on speed. The objective was to deliver a knockout blow to Saddam’s regime as quickly as possible, causing minimal damage along the way.

In the early morning of March 19, responding to what seemed reliable intelligence about Saddam’s whereabouts, the United States launched a flurry of cruise missiles at a compound outside Baghdad. But the decapitation strike did not work, and the invasion began in earnest the following day. The ground offensive involved two lines of advance from the south converging on Baghdad. Army forces, led by the 3rd ID, attacked west of the Euphrates, while the 1st MEF moved up the Tigris to the east. A British division attacked northeast from Kuwait, taking Basra and securing the oil fields nearby. And U.S. and Australian Special Operations forces secured Iraq’s western desert, suppressing Scud missile attacks on Israel and Jordan. (The 4th ID had been supposed to enter Iraq from the north, but was unable to when the Turkish parliament refused permission. It ended up being kept nearby as a decoy, and eventually deployed as a follow-on force in April.) The entire invading force—all arms and national contigents combined—totalled about 130,000 people.

Franks’s intention was that “our ground forces, supported by overwhelming air power, would move so fast and deep into the Iraqi rear that time-and-distance factors would preclude the enemy’s defensive maneuver. And this slow-reacting enemy would be fixed in place by the combined effect of artillery, air support, and attack helicopters.” The campaign proceeded largely as planned, with one exception. Iraq’s regular forces did not put up much of a fight, but irregular forces proved more troublesome than expected. Lightly armed paramilitary units loyal to the regime, primarily the Saddam Fedayeen, often came at coalition troops in a suicidal rush. They were annihilated in droves and did not seriously threaten the coalition’s success, but the need to protect flanks and supply lines from such unexpected attacks raised questions about whether to slow down the advance. Matters were further complicated by the arrival of terrible sandstorms in late March. U.S. commanders decided to continue moving forward regardless, and their boldness was rewarded as coalition forces advanced quickly in following days, helped by the pounding that U.S. air forces delivered on Iraqi positions. By April 5, the 3rd ID had reached the outskirts of Baghdad and taken Saddam International Airport, setting up positions for the Thunder Runs that led to the fall of the capital four days later.

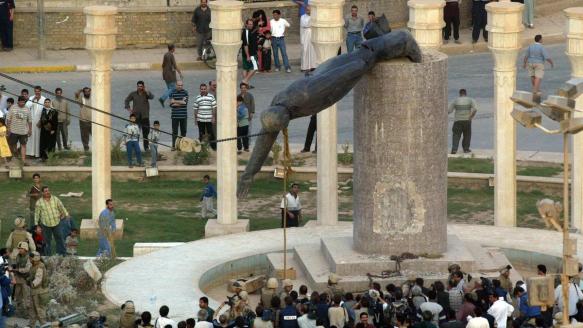

As described above, the days following the toppling of Saddam’s statue in Firdos Square were filled with joy and release, confusion and chaos. Coalition forces continued to mop up pockets of opposition while looters rampaged and public services of all kinds remained shut down. Some of this was inevitable, but what was surprising was that as the days went by, the situation did not significantly improve. Centcom’s failure to plan for maintaining postwar order came back to haunt it, as did its obsession with quick, light entry. The invading forces, it became clear, were not prepared to stabilize the country, and in any case there were far too few of them on the ground to do so. As the 3rd ID’s after-action report noted (using military jargon for postcombat activities), “3ID (M) transitioned into Phase IV SASO [stability and support operations] with no plan from higher headquarters. There was no guidance for restoring order in Baghdad, creating an interim government, hiring government and essential services employees, and ensuring the judicial system was operational. . . . [The division] did not have sufficient forces or effective rules of engagement (ROE) to control civilian looting and rioting throughout the city.”

Franks’s war plan envisioned the ORHA team arriving months after combat ended, but Garner could see that the situation was slipping out of control and pestered military commanders to let him deploy immediately from Kuwait. Realizing that he had a point, they grudgingly complied, and Garner and a few of his colleagues got to Baghdad on April 21. But the ORHA team found a city in crisis and was unable to reverse the decline. Garner’s demeanor, moreover, was not what the situation called for—less that of a bold leader than of a kindly yet ineffective substitute teacher. He frequently noted that he expected to leave soon. Asked whether he was the new ruler of Iraq, he said: “The new ruler of Iraq is going to be an Iraqi. I don’t rule anything. I’m the coalition facilitator to establish a different environment where these people can pull things together themselves and begin a self-government process.”

Rumsfeld had always considered Garner the initial head of the civilian postwar reconstruction effort—someone appropriate to oversee the expected relief and humanitarian problems that would emerge after the shooting stopped, but not somebody to handle the political and administrative challenges that would follow later on. As it became increasingly clear during April that the administration’s rosy expectations for the postwar period were being overtaken by events, a decision was made in Washington to put a more authoritative figure in place quickly. Rumsfeld told Garner himself of this decision on April 24, but neither of them nor anybody else said anything publicly about it for another two weeks. And if Rumsfeld was indeed troubled by the emerging problems, he was not so upset as to reverse his plans for pulling American forces out as quickly as possible. On April 16, as Baghdad was slipping deeper into pandemonium, he and Franks stopped the flow of U.S. troops into the theater, directed that the ones already there start moving out soon, and downgraded the status of the military headquarters running operations in Iraq.

The result of all this was that during the month after the fall of Baghdad, American policy toward Iraq proceeded on four separate tracks. Those troops actually on the ground were hastily pressed into civil affairs and constabulary duties, with varying success. At the same time, they were being readied for departure, with many of their potential replacements being stopped in their tracks. Garner, his colleague Zalmay Khalilzad, and their staffs continued with the original postwar plan, trying to restart public services and holding meetings with Iraqis as a prelude to setting up an indigenous government. And behind their backs, finally, senior officials in Washington were shifting to a hastily cobbled-together Plan B, a heavier-handed approach featuring more direct American control over the situation by a new special envoy.

As the troop drawdowns continued apace, on May 6 Bush announced the appointment of retired diplomat L. Paul “Jerry” Bremer III as the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, an organization that would absorb ORHA and assume control over all nonsecurity aspects of Iraqi governance. Bremer arrived in Baghdad on May 12, with a much different vision of his role than Garner. “My new assignment,” he would write, “combine[d] some of the viceregal responsibilities of General Douglas MacArthur, de facto ruler of Imperial Japan after World War II, and of General Lucius Clay, who led the American occupation of defeated Germany. . . . I would be the only paramount authority figure—other than dictator Saddam Hussein—that most Iraqis had ever known.”

The conventional storyline on the CPA stresses its sharp break with previous policy, embodied in “three terrible mistakes” supposedly made unilaterally by Bremer in his first days on the job—the pursuit of extensive de-Baathification, the disbanding of the Iraqi army, and the imposition of direct and open-ended American rule. But the actual situation was more complicated. De-Baathification—the purging of Saddam’s loyalists from the Iraqi government—was part of Washington’s original postwar vision. Plans for it had been formulated and approved at the highest levels of the administration weeks earlier, and Bremer’s role was simply to announce and execute them. The dissolution of the army and the rest of the Iraqi national security apparatus, meanwhile, did represent a shift in policy, but one that was approved by Washington as a legitimate response to changing facts on the ground, particularly the Iraqi army’s spontaneous “self-demobilization.” The deferral of a transition to Iraqi sovereignty, finally, seems to have been due to a mixture of second thoughts in Washington, Bremer’s own views, and deference to the new proconsul’s judgment.

The course of administration decisionmaking during these weeks is shrouded in mystery, with very few records yet available and possibly few created in the first place. As a senior administration official close to events described them to me, after the fall of Baghdad, “Things are starting to go out of control. People are really very fearful at that point about what the hell is going to happen. Garner, for all of his virtues, is not conveying any authority. . . . [Because there had been] no decision ever made about what the source of political authority would be, the country is falling apart. Bremer is sent out there, he thinks, to provide a stronger hand, and no one ever tells him otherwise. And that’s how we default into an occupation.”

The CPA, in short, was an improvisation. As Ali Allawi bitingly comments, it is “only explicable in terms of a cover for sorting out a post-war ‘Iraq policy,’ when none had existed prior to the invasion.” Nevertheless, for such an ill-starred, ad hoc, and perennially under-resourced operation, Bremer’s outfit actually accomplished a decent amount during its brief life span. Despite all the mistakes it made and the bad press it received, it was in large part a well-intentioned, serious attempt to run the country, and a marked improvement on the administration’s previous efforts in this regard. But in the end, like ORHA before it, the CPA was set an impossible task. Bremer and his colleagues confronted vast problems, were given little support and resources, and ultimately saw their efforts come to naught primarily thanks to deficiencies in an area over which they had no control—security. For as fast as Bremer’s team tried the put the country back together, it was pulled apart even faster by crime and an insurgency—problems that flourished in the vacuum created by the military’s failure to maintain public order.

As Major General William Webster, the deputy commander of coalition ground forces during the war, noted, “All along, General Franks said that the Secretary of Defense wanted us to quickly leave and turn over post-hostilities to international organizations and nongovernment organizations led by ORHA. That was the notion.” Those plans continued even though nobody emerged to take the baton. The mid-April order to stop flowing reinforcements and start sending U.S. troops home had set the U.S. military presence on a course to drop to thirty thousand by the end of the summer. “Franks explicitly stated that military leaders should take as much risk coming out of Iraq as we did going in—which meant that we were going to try to get by with the smallest number of ground troops possible,” the newly appointed coalition military commander in Iraq, freshly minted Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, would write later. Responding to Sanchez’s pleas for more troops, Franks’s Centcom successor General John Abizaid eventually halted the withdrawals, but was unable to get the Pentagon’s military or civilian leadership to send additional forces. So Sanchez never had enough resources to control the country, and had to keep moving his limited forces from hot spot to hot spot. “In effect, I was told, ‘Do the best you can with the resources available.’ So that’s what we did.”

After a fitful year, in the spring of 2004 the fires that had been smoldering in Iraq burst into flames. At the end of March, CPA officials began to crack down on a Shiite militia leader named Muqtada al-Sadr, bringing the young cleric and his Mahdi Army into open rebellion against the occupation. A few days later, four American contractors were ambushed and killed in Fallujah, leading to calls that the city be forcibly taken from the Sunni insurgents and radical Islamists who controlled it. Sanchez and Bremer did not have the strength or authority to deal with one serious challenge, let alone two. And when Washington realized just how much victory would cost, it backed down and accepted draws against both enemies, defusing the immediate crises but in the process revealing the limits of its power to all.

A few months earlier, the administration had pulled the plug on Bremer’s plan for a multiyear occupation and shifted American strategy back toward a relatively quick political handover to an Iraqi government. The CPA transferred sovereignty to an Iraqi Interim Government at the end of June 2004, which passed it to an Iraqi Transitional Government at the beginning of May 2005, which passed it on to a permanent Iraqi government in early May 2006. Meanwhile, violence proliferated and public disorder continued to deteriorate.

Stuck in Iraq long after they had expected to go home, most American military forces retreated to large, secure, and well-equipped “forward operating bases,” making occasional aggressive patrols outside to gather information, counter terrorism, and try to suppress the growing insurgency. Sunni Arabs felt disenfranchised by de-Baathification, the disbanding of the armed forces, and the empowerment of the country’s Shiite Arab majority. The Shiites were angered by the Sunnis’ past crimes and present insurgency. The Kurds jealously guarded their regional autonomy. And everybody felt threatened by the pervasive lack of personal and communal security. The center did not hold, and by the second half of 2006, more than three years after U.S. forces had conquered Baghdad, Iraq had for all practical purposes descended into civil war.