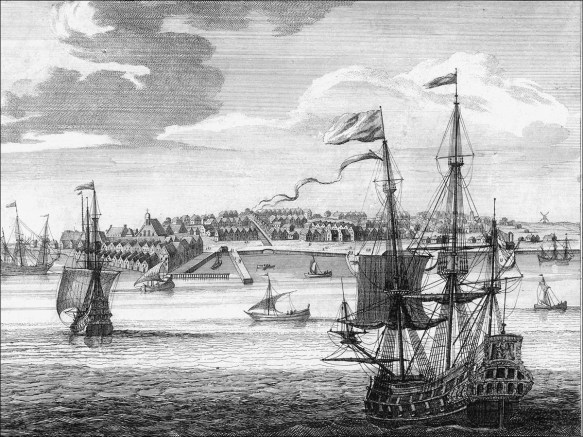

Port Royal as it appeared before the earthquake in 1692. The outer edges of the map are the borders of the old Port Royal, while the darkly shaded area toward the bottom and middle depicts the boundary of the city after the earthquake. The rest of the city was consumed by the sea.

In the summer of 1690, three French privateers appeared off the coast of New England, panicking the region. This was in the midst of the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697), known as King William’s War in the colonies, which arrayed most of Europe against the French. The privateers had already attacked Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, Fishers Island, and Block Island, where they ransacked houses, killed livestock, commandeered vessels, and whipped residents to get them to divulge where they had hidden their valuables. Word of the atrocities soon spread to the mainland, where the people of Newport, Rhode Island, were sure they would be next. The governor’s council met in emergency session and commandeered the Loyal Stede, a Barbadian sloop‡ moored in Newport Harbor, with ten cannons and a crew of sixty. All they needed was someone to captain the vessel, and since there was no one in the colony who knew more about naval warfare than Captain Thomas Paine, he was chosen to lead.

Along with another sloop manned by thirty men, Paine sailed out of Newport Harbor, heading toward Block Island. Upon learning from the locals that the French had set off for New London, Paine went in pursuit, sighting the enemy vessels soon thereafter. For two-and-a-half hours the battle raged. Early on, the captain of one of the French sloops, “a very violent, resolute fellow,” poured himself a glass of wine, and declared that it would “be his damnation if he did not board” one of the English vessels immediately. It proved a hollow boast. As he raised the glass to his lips, a bullet ripped into his neck, killing him instantly. Before darkness brought an end to the fighting, another Frenchman lay dead, along with an Indian who had fought with the English.

The contestants anchored for the night a short distance apart. Paine was sure that the fight would recommence in the morning, but shortly before dawn, the French vessels sailed away. A contemporary account claims that the Frenchman in charge of the fleet had been a privateer with Paine in an earlier war, and when he learned “by some means” that he was up against his old captain, he said that he “would as soon choose to fight with the devil as with him.” Whether he fled for this reason or some other, the French were gone, and Paine and his men returned to a hero’s welcome in Newport.

Although the number of pirates visiting and settling in the colonies was relatively small, they had an outsized impact on colonial life because the colonies themselves were sparsely populated. In 1690 there were just over 190,000 American colonists, along with about 17,000 slaves, thinly spread out along the eastern edge of the continent, with most people living within a few miles of the coast. Even the largest port in the colonies, Boston, had only 7,000 residents. Consequently, the considerable amount of money, goods, and muscle provided by the pirates was enough to make them a significant economic, social, and military force.

Just as pirates benefited the colonies, the colonies offered pirates valuable resources and opportunities in return. Colonial ports were places where pirates purchased supplies, sold stolen goods, recruited men, sought medical help, enjoyed liquid and libidinous entertainment, and settled down at the end of their piratical career, assuming they survived long enough to enjoy retirement. As important was the chance for pirates to careen their vessels.

Over time a vessel’s hull became fouled with all manner of organisms, from seaweed to barnacles, which not only increased drag and slowed the vessel down, but also caused serious damage. The worst were the Teredo worms (Teredo navalis), a form of mollusk that burrows into wood, creating tunnels and turning it into a pulpy mess that has a passing resemblance to Swiss cheese. Careening—essentially tipping the vessel on its side with the help of ropes to expose parts of the hull that are usually underwater—allowed the men to scrape the hull clean, replace rotted or riddled wood, recaulk leaky seams with oakum, and recoat the hull with an oily mixture of tar, sulfur, and tallow, thereby extending the life and improving the performance of the vessel. Specialized wharves in larger ports enabled pirates to careen their vessels, and if such wharves were lacking, careening could be done in sheltered coves or embayments along the coast.

By offering all of these benefits, the colonies provided pirates with a beachhead that enabled them to pursue their disreputable designs. Without such support, pirates couldn’t have survived, much less thrived. Therefore, the colonies were, in a very real sense, the pirates’ partners in crime.

The acceptance and support of pirates by the colonies was not absolute. While pirates were welcomed when they provided money, goods, and protection, they were not embraced when they practiced their “profession” in coastal waters, as the case of Thomas Pound reveals.

In the early morning of August 9, 1689, Pound and twelve armed associates sailed a small sloop out of Boston Harbor, their ultimate goal being to reach the Caribbean and prey on the French. But first they needed a better vessel, and more men, food, arms, and ammunition. The next day, they overpowered a fishing ketch§ called Mary out of Salem, captained by Halling Chard. Pound’s men took the ketch, thereby officially launching their piratical voyage, and sent Chard and two of his crew away on the sloop, while another of Chard’s men, John Darby, voluntarily remained behind—a rather strange, selfish, and rash decision, as he was leaving behind his wife and five children in Marblehead. Pound and his men next headed to Casco Bay, where they stole a calf and three sheep from one of the bay’s many islands, and then moored off Fort Loyal, a small garrison located in what is today Portland, Maine.

Darby went ashore with two other men. While the men got water, Darby introduced himself to Silvanus Davis, the garrison’s commander, who asked where they had come from. Darby said they had been fishing off Cape Sable when a French privateer attacked them, stealing their bread and water before letting them go. Being familiar with the Mary, Davis asked why Captain Chard hadn’t come to the fort. He hurt his foot, Darby responded, adding that all they wanted was water, and for the local doctor to visit the ketch to tend to the captain. That, of course, was a lie. Pound’s real intention was to convince the doctor to join his southern venture, since medical expertise was in high demand on pirate ships, where injury was an occupational hazard, and going ashore to find a willing practitioner was rarely an option.

Darby’s answers put Davis on alert. His suspicions heightened when his men visited the Mary and reported that it contained a far larger crew than a typical fishing vessel, and Captain Chard was nowhere to be seen. Davis began to fear that the visitors might be “rogues.” Nevertheless, Davis allowed the doctor to be ferried to the ketch, but when he returned to shore—unconvinced by Pound’s pleadings to sign on—the mystery deepened. The doctor seemed nervous, and kept changing his story about how many men were on the ketch, causing Davis to think that the doctor was involved in some wicked plot. Most likely shaken from the encounter with Pound, it wasn’t the doctor that Davis should have been worried about. Unbeknownst to him, two of the soldiers who had visited the Mary earlier that day had agreed to join Pound, promising to enlist other soldiers as well.

That evening, Davis set armed guards around the fort and told them to keep a “good watch” on the “water side.” At midnight, seven soldiers who had decided to cast their lot with Pound rose up and trained their guns on their fellows. Gathering all the arms, ammunition, and clothes that they could carry, the traitors took the fort’s boat out to the Mary, and soon thereafter Pound set a course for Cape Cod.

A day later, off the highlands of the Cape (modern-day Truro), Pound captured the sloop Goodspeed and traded up once again, transferring his men, and sending off the Goodspeed’s crew in the Mary. He also sent a message. Pound told the Goodspeed’s crew to tell the authorities in Boston that if the government’s sloop “came out after them,” it would “find hot work,” for every last one of his men would die “before they would be taken.”

As it turned out, acting on intelligence provided by Captain Chard, the colonial government had already sent out an armed vessel to search for the pirates, and it would send out another after the Mary sailed into Boston Harbor. Both ultimately came up empty. Meantime, Pound and his men traced a circuitous route. They stopped on the Cape and Martha’s Vineyard to get more livestock and water, and on August 27 at Holmes Hole (modern-day Vineyard Haven), they robbed a brigantine¶ of food, rum, and tobacco, and then released it. Next, a ferocious storm forced them to Virginia, where they sheltered in the York River for eight days, picking up two more men and a slave. When calm seas returned, they headed back to Tarpaulin Cove, on Naushon Island, just off Martha’s Vineyard. Over the next few weeks, Pound sailed between the Cape and the Vineyard, unsuccessfully chasing one vessel, and capturing two, one of which was plundered for food. At the end of September, the peripatetic pirates returned to Tarpaulin Cove to wait for good weather to sail to Curaçao.

Massachusetts governor Simon Bradstreet, alarmed by these continued depredations, ordered Pound’s former ketch, the Mary, to be manned by twenty soldiers and sent to bring the “pirates” to Boston to face justice, using deadly force to “subdue” them if necessary. Captain Samuel Pease was put in charge, and he embarked on his mission from Boston Harbor on September 30, looping around the outstretched forearm of Cape Cod, then heading west toward Vineyard Sound. On October 4, Pease spied a canoe coming from Woods Hole into the channel. A man in the canoe said that “there was a pirate in Tarpaulin Cove,” and upon hearing that, Pease’s men “gave a great shout” and made ready for battle.

Not long thereafter, Pease saw the Goodspeed in the distance and ordered his men to bring their ketch in close. The pirates tried to flee but the Mary was a better sailer and quickly closed the gap. Once the Goodspeed was within range, the King’s Jack was raised up the Mary’s mainmast, and cannon and musket shots were sent across the Goodspeed’s bow as a warning. Defiant, Pound’s men raised their own “bloody [red] flag,” which signaled that no quarter would be given, and arrayed themselves on the main deck, ready to fight.

Pease demanded that the pirates “strike to [the] King of England,” but Pound was not cowed. Standing on his quarterdeck, he flourished his sword, and barked across the water, “Come aboard you dogs, and I will strike you presently.” No sooner had Pound issued this bellicose invitation than the shooting began. Pound took a ball to the arm, and one just under the ribs, while Pease was struck in the arm, the side, and the thigh. Both men were then taken below. The soldiers repeatedly implored the pirates to give up, telling them that they would be given “good quarter,” but the pirates scorned the offer. “Ye dogs,” they yelled, “we will give you quarter.” An hour after the first shots were fired, the soldiers swarmed onto the Goodspeed, getting off one good volley, and then using the butts of their muskets to mercilessly beat the pirates into bloodied submission. When the smoke cleared, four pirates were dead, and most of the rest were wounded, while five of the soldiers were injured. Among the dead pirates was John Darby, whose wife and children back in Marblehead were left to fend for themselves.

With the pirates secured, the Mary and the Goodspeed sailed to Rhode Island, where the wounded were taken to lodgings on the mainland and treated by doctors from Newport. But there was little they could do for Pease, who died of his wounds on October 12. A week later, the ships sailed into Boston, and the pirates were kept in the city jail under heavy lock and key.

The men of the Goodspeed were brought to trial in 1690 on charges of piracy and murder, and although fourteen of them were found guilty and sentenced to hang, that never happened. For reasons that are not entirely clear, a number of substantial citizens of the colony urged Governor Bradstreet to be lenient. Among the pleaders were a few “women of quality,” and Waitstill Winthrop, the grandson of former governor John Winthrop and one of the magistrates who conducted the pirates’ trial. Bradstreet complied, the result being that only a single pirate was hanged. The sentences for all of the rest, except for Pound, were remitted. For one of those set free, the pardon came at the penultimate moment, just as he was on the scaffold ready to swing. According to a member of the governor’s council, this sudden turn of events caused “great disgust to the people,” who were hoping for a show. As for Pound, his sentence was only reprieved, and he was sent back to England in the spring of 1690, where again, for reasons that remain unknown, all charges were dropped.

Around the time that Pound was on the loose, a dramatic shift was taking place in the annals of piracy. Although pirates continued to terrorize the Caribbean, their numbers were declining as tropical hunting grounds became far less attractive to would-be marauders. Spanish treasure fleets were being more heavily guarded to protect against attack. Government crackdowns on piracy in Jamaica and elsewhere in the region were making the lives of pirates more difficult as well. Furthermore, even though the flow of silver and gold coming from Spain’s possessions in the New World was still considerable, it was far less than it had been in former years.

As if to provide a fiery and dramatic symbol marking this decline, on June 7, 1692, just before the noon hour, a devastating earthquake struck Jamaica. In the pirate haven of Port Royal, buildings toppled and the streets were transformed into rolling rivers of liquefied earth that sucked people under and then crushed them to death when the shaking stopped and the soil solidified. Some of those trapped had only their heads sticking above ground, which roving packs of starving dogs gnawed upon in the ensuing days. When it was all over, nearly two-thirds of the landmass of Port Royal had slipped beneath the waves, and the death toll, including those who later succumbed to injuries and disease, approached five thousand—many of them buccaneers. In the gruesome aftermath, hundreds of dead and bloated bodies could be seen floating on the surface of the harbor, and washed up on the shore, where they became, according to one eyewitness, “meat for fish and fowls of the air.” A local minister who survived called the earthquake a “terrible judgment of God” that was brought down upon the heads of the “most ungodly debauched people” in the world.